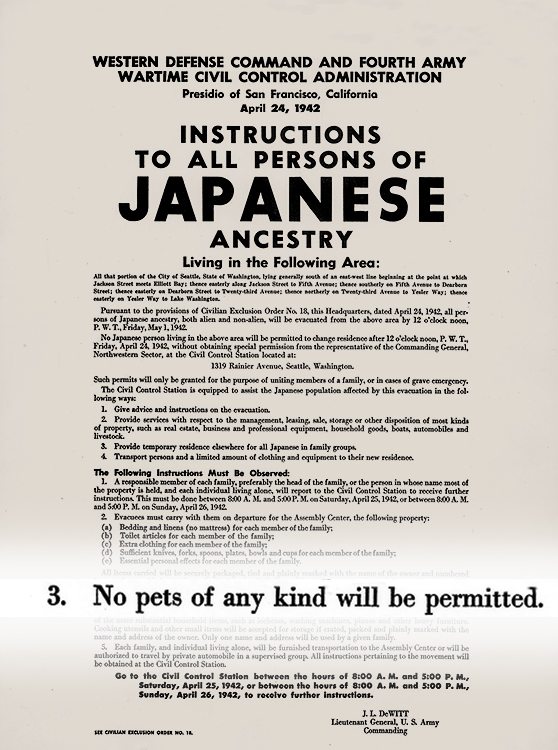

As beloved as a family member, yet uncounted in the tally of 110,000 people exiled from their homes, were the thousands of pets that were left behind. With little advance notice, owners had to quickly make arrangements for their cats, dogs, birds and other animals. Pets were hurriedly deposited with strangers or friends. Many were simply abandoned.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Yaeko Munemori was a young adult when her Los Angeles family tied their dog to a post before they left for Manzanar, 200 miles away. “On that Sunday, as they rode off in the Army truck…the dog began yelping and straining at his leash. Long after house and dog were out of sight, she could still hear him crying.

How do children cope with such traumatic separations? Amy Iwasaki Mass realized later in life that “taking her pet to be left at a neighbor’s was so disturbing that she had repressed the memory. She finally remembered years later when her older sister began talking about how difficult this event had been for Amy.”1

According to an exhibit at the World War II Japanese American Internment Museum in McGehee, Arkansas, a man recounted the case of his father who “tried to hand off the family dog to a friend for safekeeping until he returned.”

“The man accepted care of the pet and promptly shot it.”2

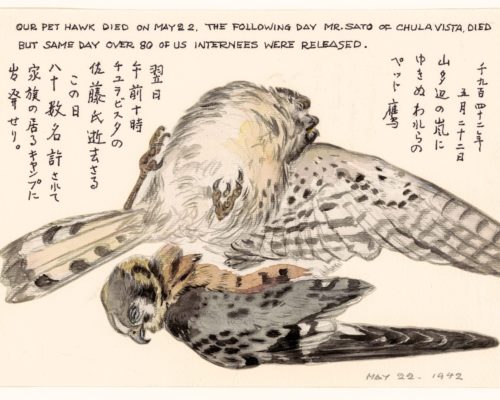

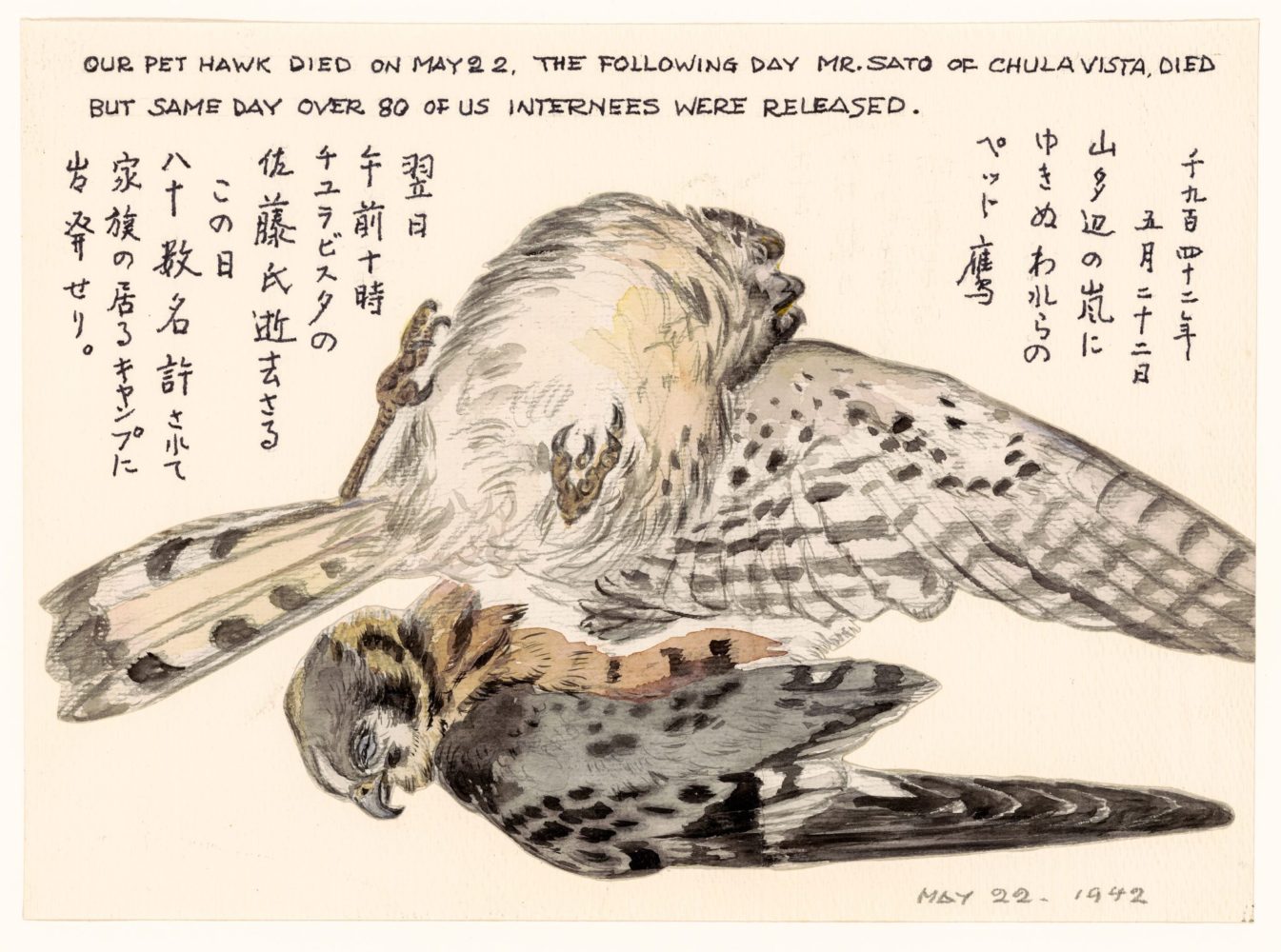

One wonders if the carvings and drawings of animals that were made behind barbed wire were in some way a personal, even communal expression of this sudden and cruel separation.

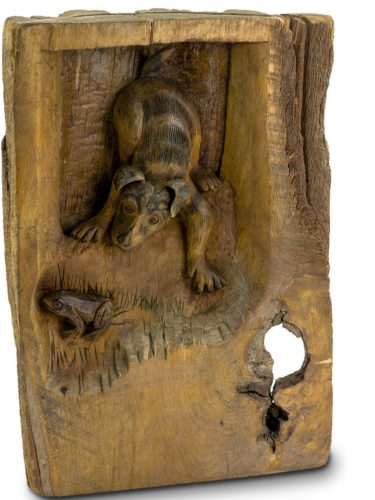

The object featured here was sculpted from a log at the Granada prison camp, more popularly known as Amache, in eastern Colorado.3

The carver, whose name is not known, conjured a scene that feels like a storybook moment. A playful pup, a frog and a small crevice are portals into a world far from confinement. Amache opened on August, 27, 1942. About half a year later, formal permission was granted for dog ownership as seen in rules agreed to by the administration.7

Across the camps, regulations regarding pets were relaxed. Some families were able to get a pet brought in. Strays multiplied. When the camps closed several years later, however, people again had to leave their pets behind and many were put down as a humane measure, according to a WRA photographer.8

With this carving, we pay homage to the memory of people and the animals they cared for at Amache, Poston, Topaz, and Heart Mountain.

Poston's Pet

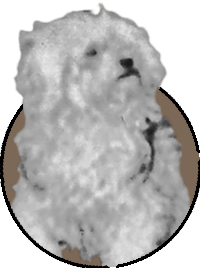

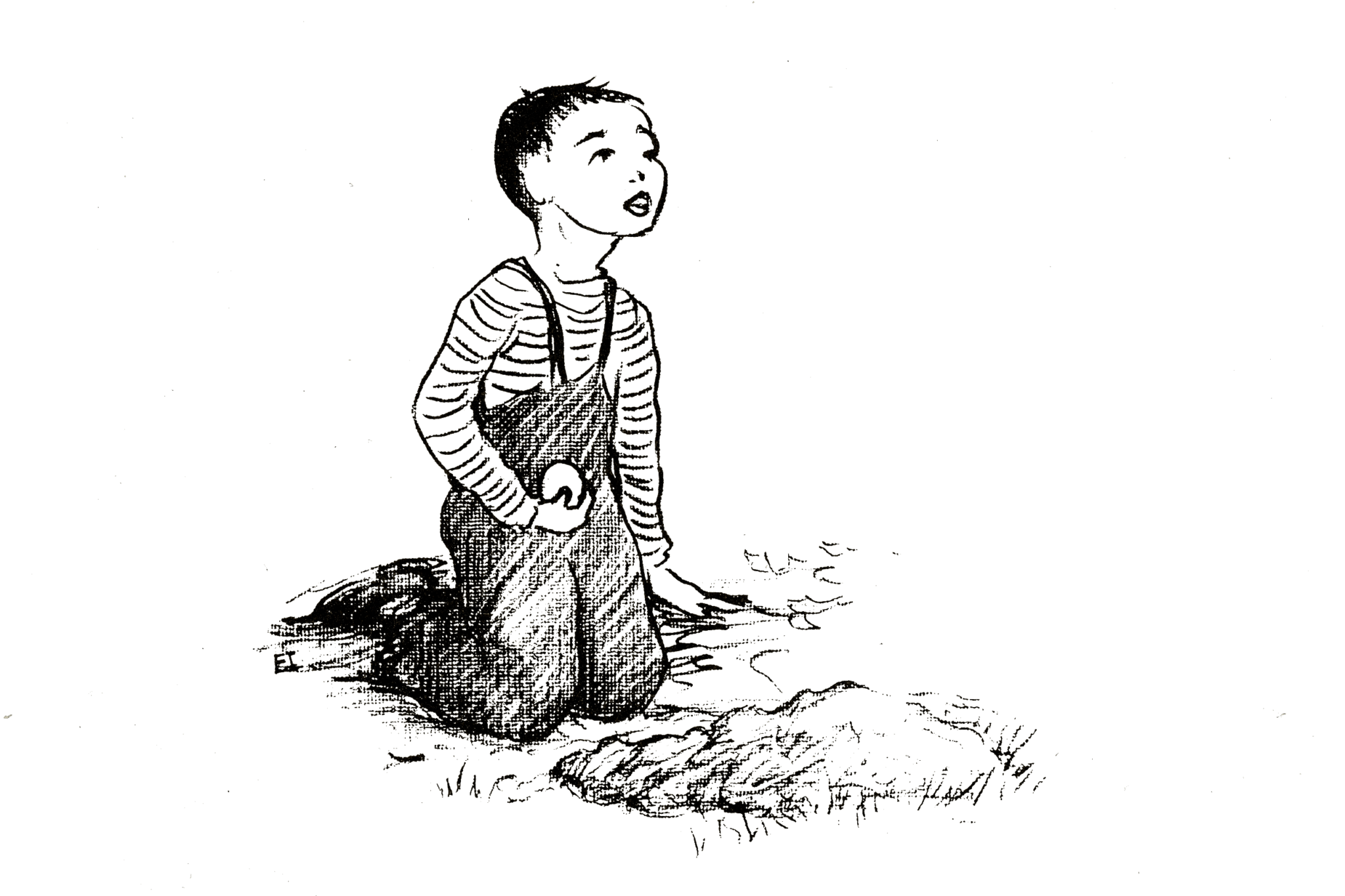

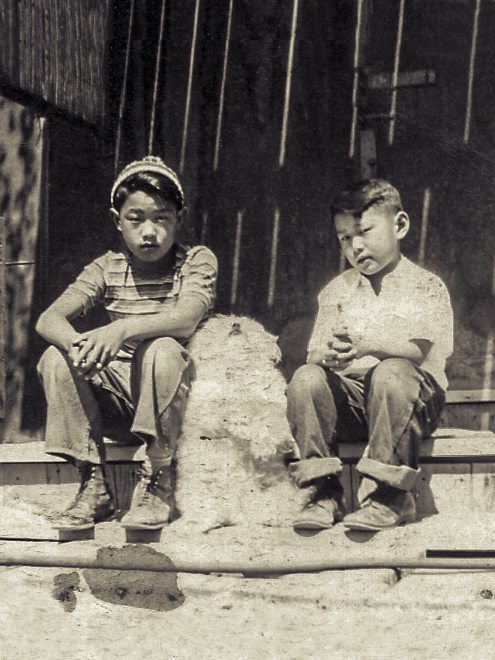

Mas Hashimoto’s family raised canaries in an aviary behind their home in Watsonville, California. One of his sweetest childhood memories was the day that some of the canaries were traded for a puppy and Sunny, a bundle of white fur, entered the lives of the Hashimoto brothers. But “when the war came along, we were to evacuate, we couldn’t take Sunny, no pets are allowed. And that was, that hurt.”

block 220-12-A.” Courtesy of Mas Hashimoto.

Mas was six years old. “Sunny was my best and most loyal friend.” The family boarded up the house and gave their brand new refrigerator, the kitchen stove and typewriter to their friend, Stacy Irwin. Stacy also took Sunny. “But our dog was not eating well, and so (Stacy) wrote to us,” Mas recalls. “When we got to Poston, Arizona, Stacy asked if the dog could be sent to us because she didn’t want the dog to die under her care.”11

Stacy proposed a novel way to deliver Sunny to Poston II, nearly 600 miles away: Greyhound bus. The unorthodox plan was executed perfectly.

Mas, now 80, doesn’t know how official permissions were granted, but Sunny arrived safely and overnight became the entire camp’s pet, a fluffy white creature adopted by 18,000. “She was the petting zoo, everybody wanted to pet her, especially the younger children. Cause you couldn’t exactly pet a rattlesnake or a scorpion” in the desert.12 (For full story, see the following video).

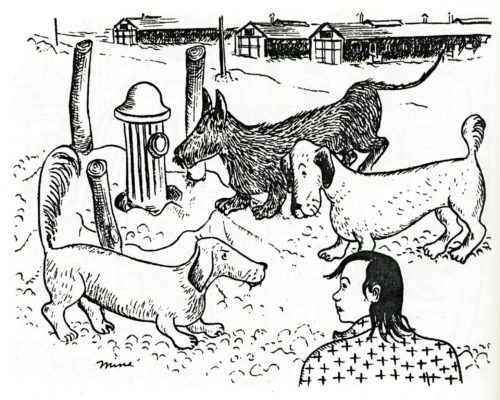

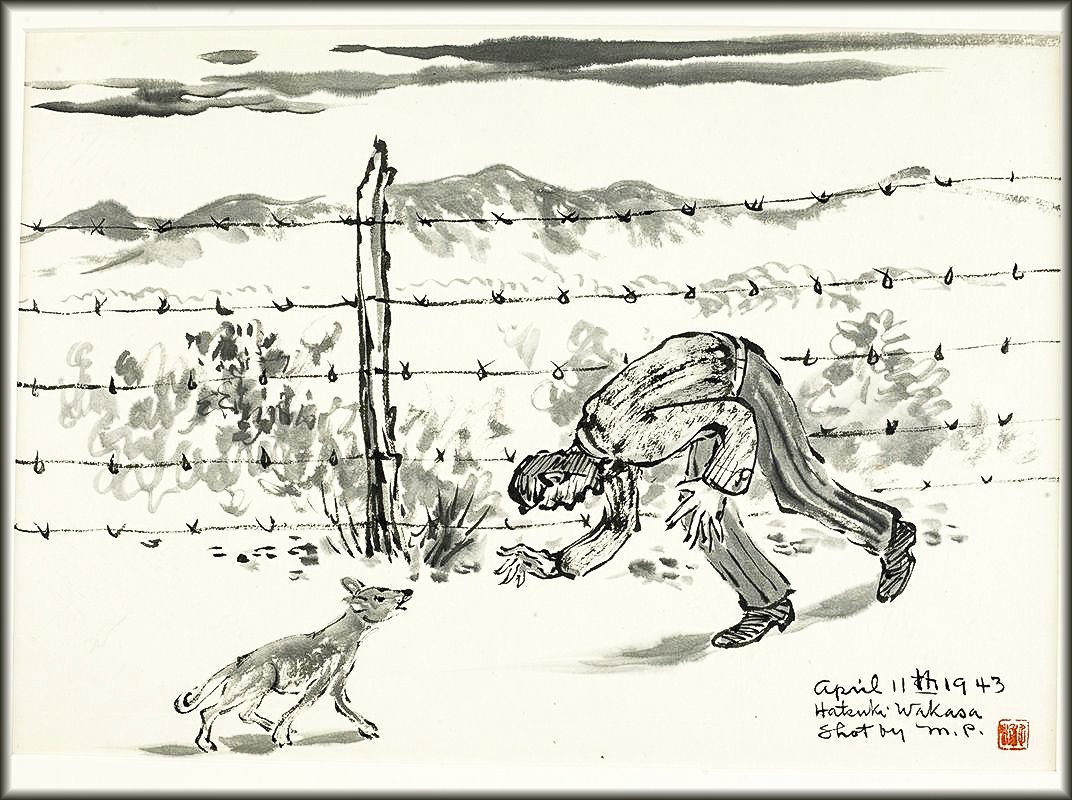

Mr. Wakasa's Dog, Witness to a Killing

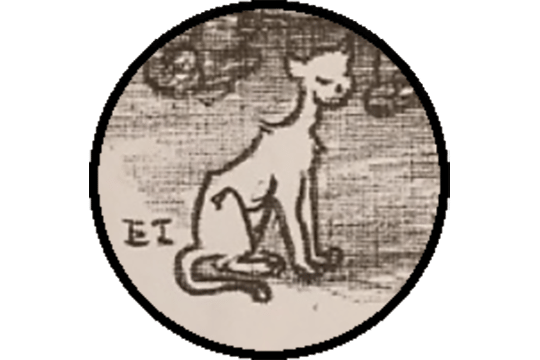

On April 11, 1943, half an hour before sunset, James Hatsuaki Wakasa was walking a dog, perhaps a stray, inside the fence at Topaz, Utah, when he was shot in the chest and killed instantly. The presence of a dog at the killing was memorialized in a brush painting by the artist Chiura Obata and also in a military transcript of a court-martial at Fort Douglas, Utah.

Sumi on paper, 11″ x 15 3/4″

Courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Private Frank R. Baughman, a sentry in guard tower No. 9, testified in military court that he saw the dog “prancing” near Wakasa at the time Private Gerald B. Philpott, of Durham, N. C., shot Wakasa from guardtower No. 8, from a distance of more than 200 yards.

Q. “Did you look toward Post No. 8 after you heard the shot?”

A. “Yes sir I did.”

Q. “What did you see, if anything.”

A. “I could see a little dog prancing around down there.”

Q. “Was that the same dog that was with the person loitering around your post a few minutes before?”

A. “Yes sir.”15

The military said that Wakasa was trying to escape by “crawling through the fence” but the WRA Internal Security report stated that Wakasa’s body was facing the shooter. It was parallel to the barbed wire, “40 to 65 inches from the fence,” according to the Topaz final report.16

Community lore for decades afterward recalled Mr. Wakasa, 63, as an elderly immigrant who kept a dog. Few knew that Wakasa, a chef by trade and a bachelor, had been a student at the elite Keio college in Tokyo and at the University of Wisconsin. He had been living in San Francisco when the military roundup ensnared him.

A questionnaire sent to Topaz survivors in 1989 elicited personal memories.17

Miyoko Nakagawa recalled that her parents thought the dog was a stray. “My mother and father said he had a dog and always took him for a stroll around the fence. Since he was in Block 36, the desert was very appropriate for his dog to walk around.”21

David Kitagawa wrote that Wakasa “was careful not to let his dog run around loose or bother others…He was not trying to escape. There was no need to shoot him.”22

All work stopped the next day and male inmates armed themselves with clubs and anything “that could be used as a weapon” a teacher at Topaz, Mel Roper, recalled.23 Two days later, news of the military arrest of Philpott headlined the front page of the Topaz Times. Below the article was an announcement that the keeping of wild animals for pets was increasing at an “alarming” rate, heightening the danger of disease.24

But the court-martial result — that Philpott, 21, was “fully and honorably acquitted”25 by a secret written ballot of the court — was never published in the Times.

Wakasa’s belongings, including a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, were inventoried by the War Relocation Authority. There was no further record of the dog, which remained unaccounted for after his master’s death.

Census

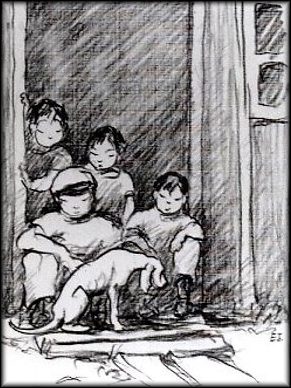

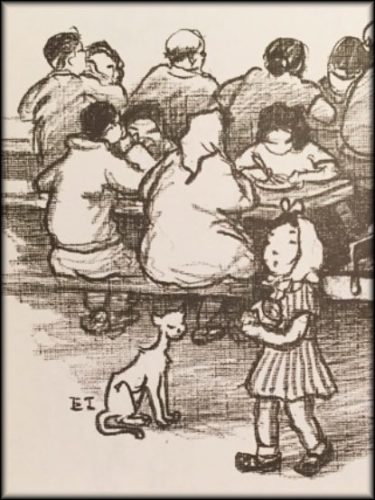

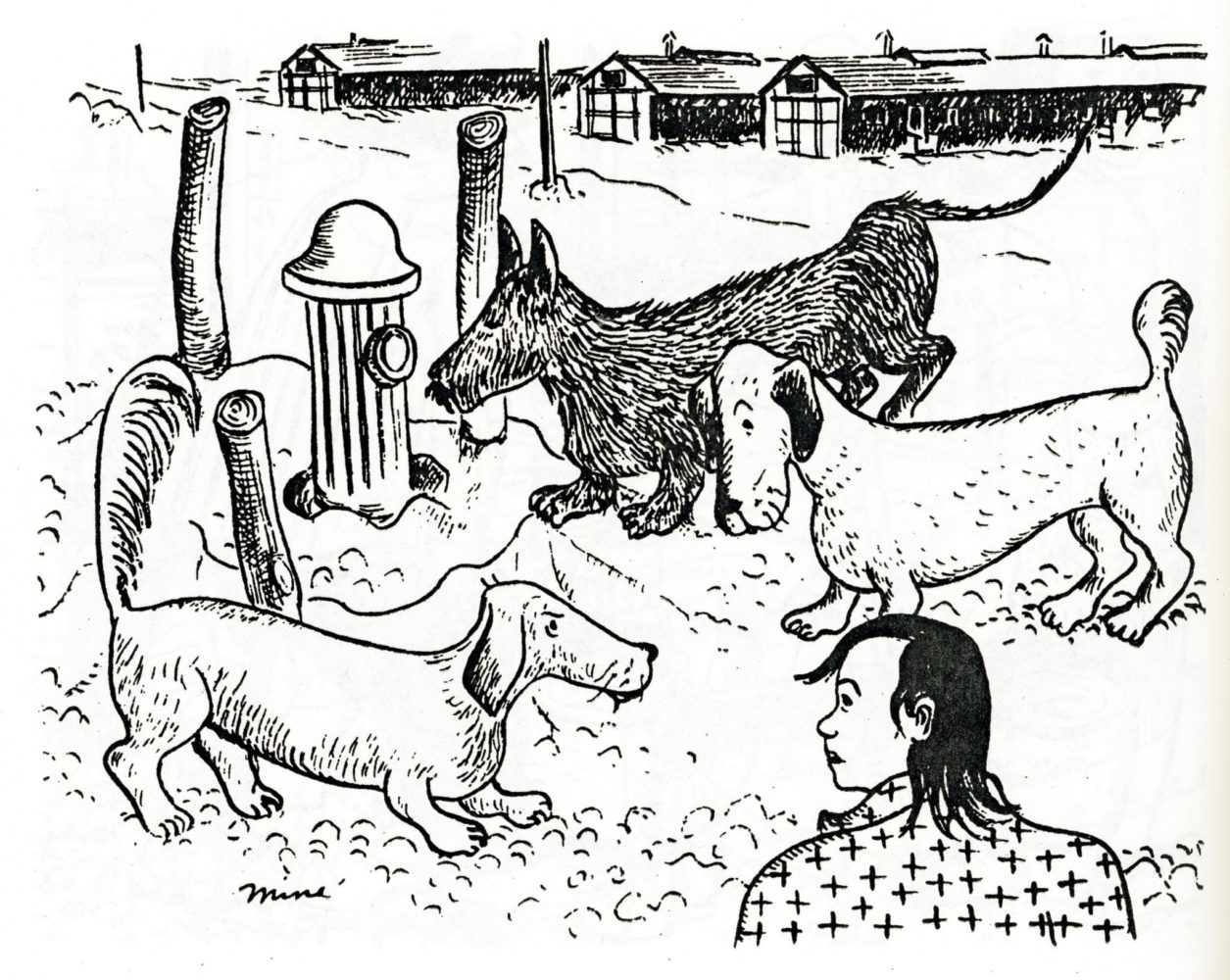

Estelle Peck Ishigo was a Caucasian artist who was imprisoned with her Los Angeles-born Nisei husband, Arthur, because she refused to be separated from him. They spent four years in exile in Wyoming during which Estelle was employed by the WRA Reports Division to create visual documents of life at Heart Mountain. Her sympathetic sketches of people enduring life at the temporary Pomona detention center and the Wyoming concentration camp often included animals.

Ishigo was a copious notetaker and left behind a detailed and unique document — a census of dogs and cats at Heart Mountain with the names of their owners and their barrack addresses.31 The year is not recorded.

collection of UCLA Library Special Collections

The two-page document lists a total of 51 pets (26 cats, 25 dogs) sheltered in 16 blocks, the military police quarters and a mess hall. One cat, listed halfway down the first page, entered below “S. Kohno,” doesn’t have an owner — the Mess Hall is its caretaker. The Heart Mountain pet census does not include winged pets, such as the baby bird protected and released by Naoko Yoshimura Ito with her brother, Akira, or the injured magpie rescued by Shig Yabu when he was 10 years old.32

Bird Man of Topaz

At age 20, Hiroo Niwa had emigrated to the U.S. in 1905 with dreams of being a painter but he switched to music, taking up the violin while living in the East Bay of northern California. Thirty seven years later, incarcerated at Topaz, Utah, he was visited by the folk art scholar Allen H. Eaton, who wrote in “Beauty Behind Barbed Wire” about the wild birds Hiroo had trained to live in his barrack.

“As soon as we were seated in his tiny room, he went to a pretty bird cage, which he explained a neighbor had made for him from scraps of wood and metal; he released a beautiful pair of Baltimore orioles.

“One flew to a branch fastened to the wall near the window, the other to his hand, while he told of his love for wild birds, especially, and the pleasure of taming and caring for them.

“The pair he had found about a year and a half before, during a walk at the base of Drum Mountain, about 16 miles from camp; they were only two or three days old then. ‘It is molting time now, and they do not look their best’….but they seemed to us to be in perfect condition, and satisfied in their manmade abode.

‘They like cake,’ he said, and took some from a box; both birds flew to his shoulders and one took crumbs from his mouth. He explained that too much cake was not good for anybody, of course, and that it required quite some time to find the worms and catch the insects the birds liked best. But the children in the block were willing hunters, and some of them quite expert.

“In another block of Topaz, we came across a tame bird that seemed to belong to all the children of that section — a sparrow sitting on the railing at a barrack entrance; when we did not respond to its chirps for food, it flew down the street to some children who seemed likelier prospects.”37

Credits

by: Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: Clem Albers, Estelle Ishigo, Yoshio Okumoto, Hikaru Iwasaki and Nancy Ukai

Special thanks to:

John Hopper, Mas Hashimoto, Kimi Kodani Hill, Noriko Sanefuji, Bacon Sakatani, Joan Myers, Saburo and Marion Masada, Melissa Van Otterloo, Aaron Marcus, Elisa Phelps, Stacey Camp, Alisa Lynch, Bernadette Johnson, Amache Preservation Society, Manzanar National Historic Site, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Japanese American National Museum

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites program