When Mickey Mouse debuted 90 years ago this Sunday, no one suspected that the cartoon rodent would become a global icon in the years to follow, his image gracing everything from royal teacups to wind-up toys.

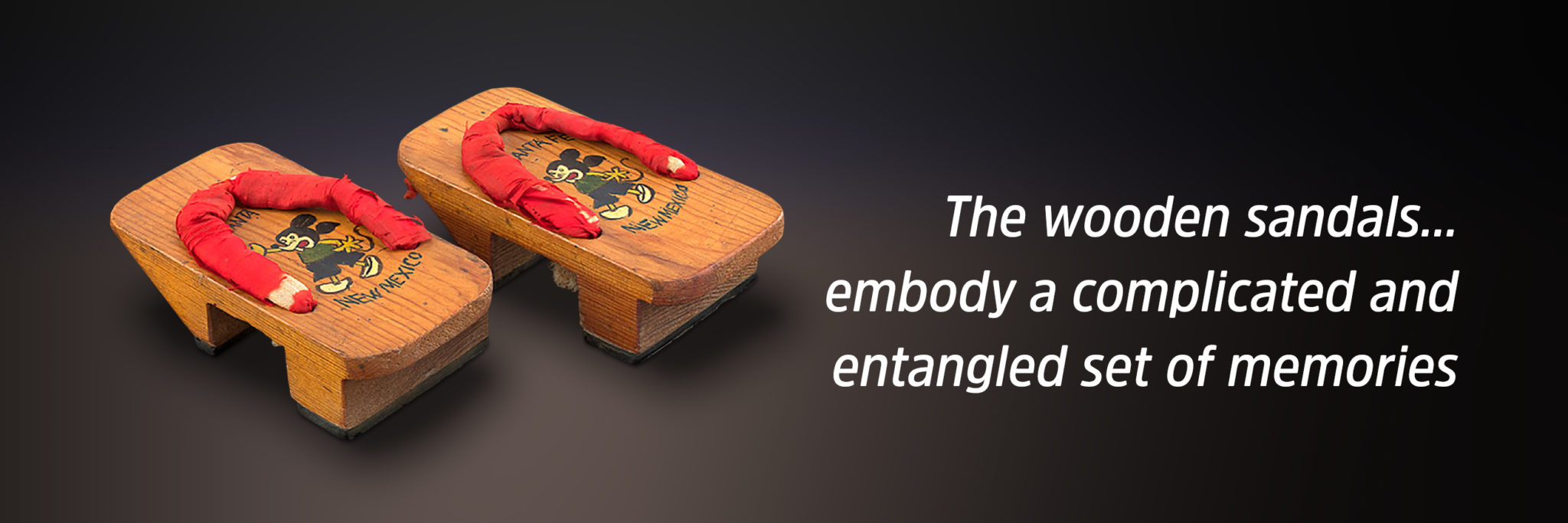

One of the most unusual objects to bear Mickey’s image was a pair of Japanese wooden sandals, called “geta.” The geta, made by hand in 1942 or 1943, showed the mouse waving jauntily from Santa Fe, New Mexico, as if the shoes were a holiday souvenir.

But this Mickey item was made behind barbed wire, in a Japanese American internment camp. The sandals were made for a boy named Goro in a different detention camp, hundreds of miles away. An American Japanese family had been separated and Mickey Mouse was being sent, from a father to a son, to deliver a smile.

The father was Jingo Takeuchi, a Japanese immigrant who had lived in the U.S. for 37 years. Within months of Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Jingo was arrested by the FBI under suspicion of espionage and sent to an enemy alien internment camp in New Mexico.

He left behind his seven American-born children and wife, Kiwa, in the northern California city of Alvarado. Goro was seven years old.

No one knew exactly why Jingo had been arrested.

It may have been that his leadership in promoting kendo, Japanese fencing, made him suspect. Also, the three eldest children had been educated in Japan, a not uncommon practice for immigrants at the time, but viewed with suspicion by the U.S. government. An intelligence report stated, “He is very much attached to his homeland and is a potentially dangerous alien enemy.”1

Government records, declassified decades later, also showed that an informant had reported him.2

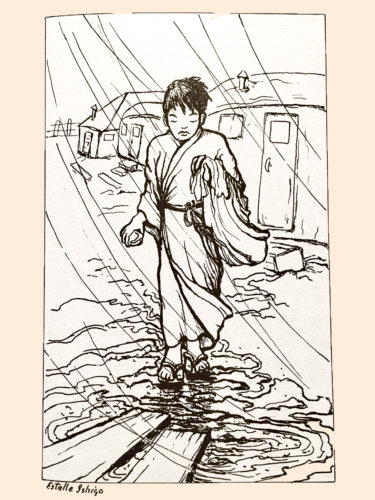

Two months after Jingo was arrested, the rest of the Takeuchi family was rounded up, too — sent first to the Tanforan racetrack, south of San Francisco, and then to Topaz, Utah, as a result of President Roosevelt’s executive order that forced 110,000 American Japanese, most of them citizens, into detention camps.

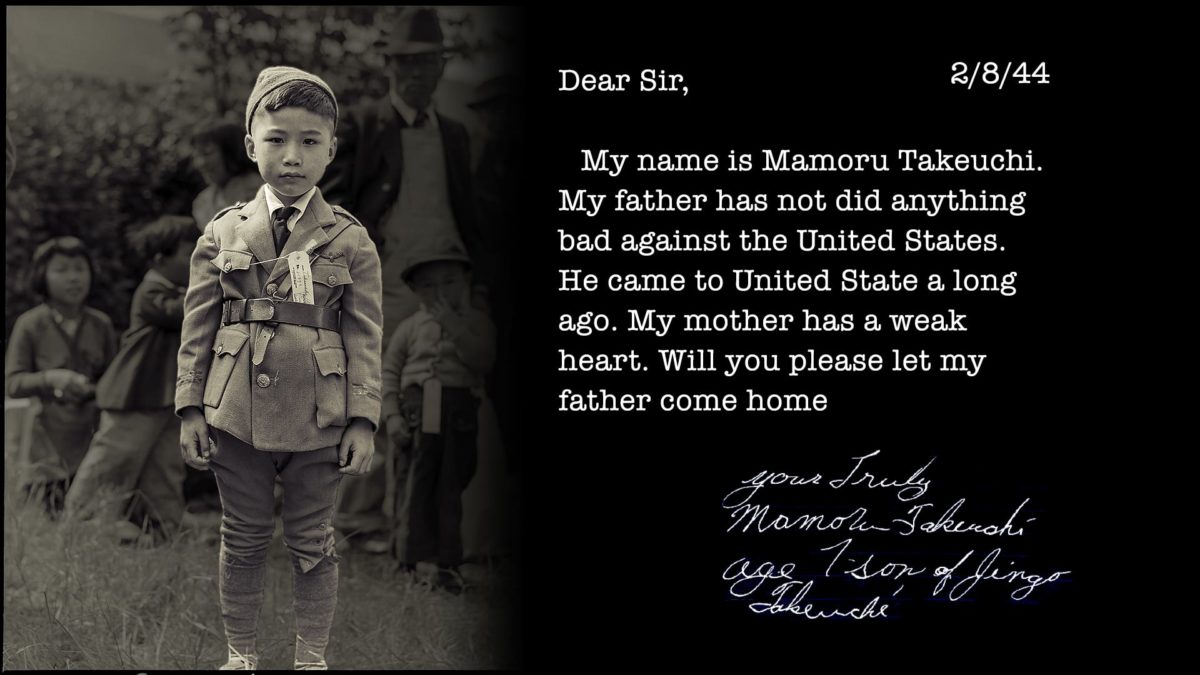

On the day the Army removed the Takeuchi family, Goro’s younger brother, Mamoru, in a necktie and military uniform, was tagged and numbered.

with text of Mamoru Takeuchi's letter to the Department of Justice

in photo collage by David Izu.

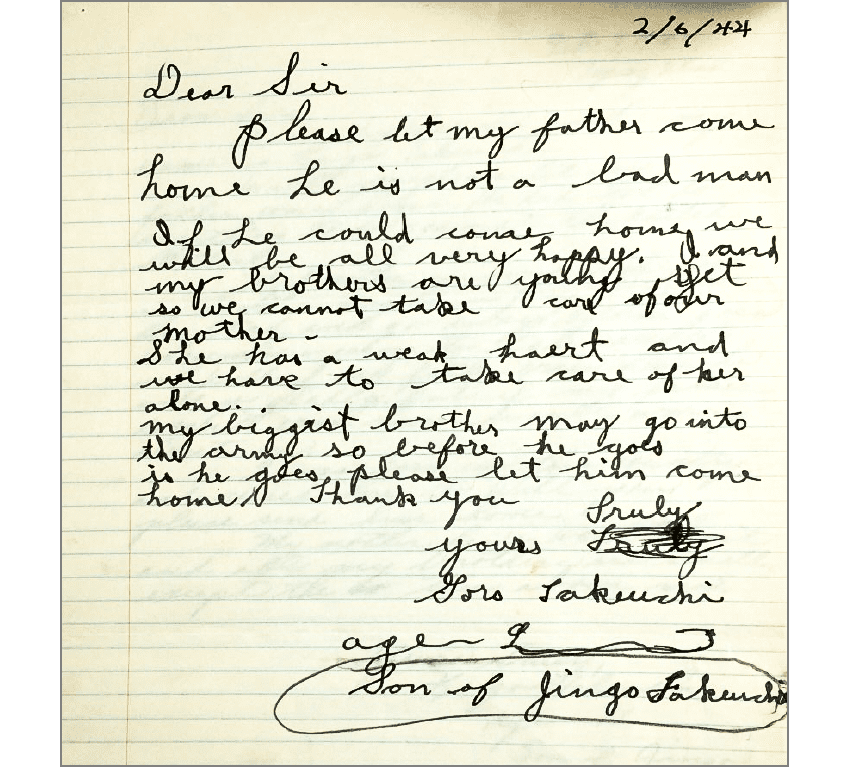

A letter writing campaign to release Jingo continued. In careful cursive, Goro wrote from Block 37: “Please let my father come home. He is not a bad man. If he could come home we will be all very happy. I and my brothers are young yet so we cannot take care of our mother.”5

Letter from Goro Takeuchi to the Alien Enemy Control Unit, Department of Justice, Feb. 6, 1944. National Archives.

Mickey Mouse on kimono and geta

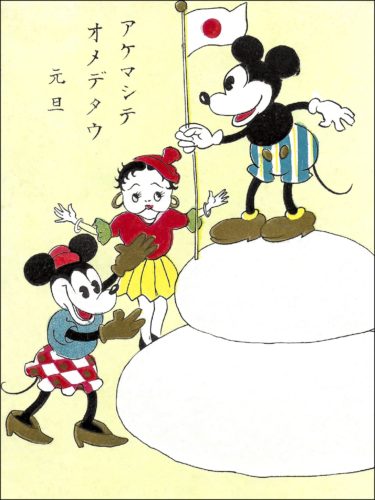

Jingo was born in Kumamoto, Japan, in 1888. After arriving in the U.S. in 1905, at age 17, he never returned, but if he had done so in the 1930s, he would have seen that Japan had adopted Mickey Mouse to adorn everything from kimono to candy wrappers.

A New Year’s card from the mid-1930s, for example, shows Mickey planting a Japanese flag on two mochi rice cakes, a holiday delicacy, to the delight of Betty Boop and Minnie Mouse.

So it was not entirely odd for Mickey Mouse to land on Japanese geta in the middle of World War II.

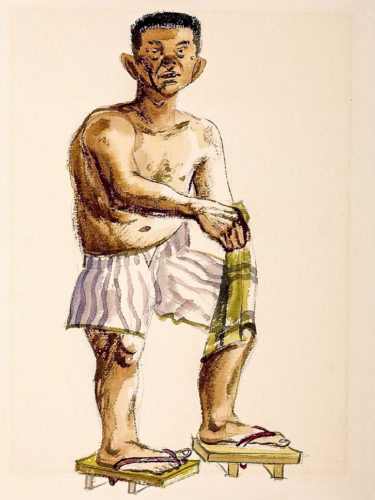

What was unique in the history of geta was for innocent American citizens and Japanese immigrants to wear the wooden flip flops, made from scrap lumber, while incarcerated in U.S. concentration camps.

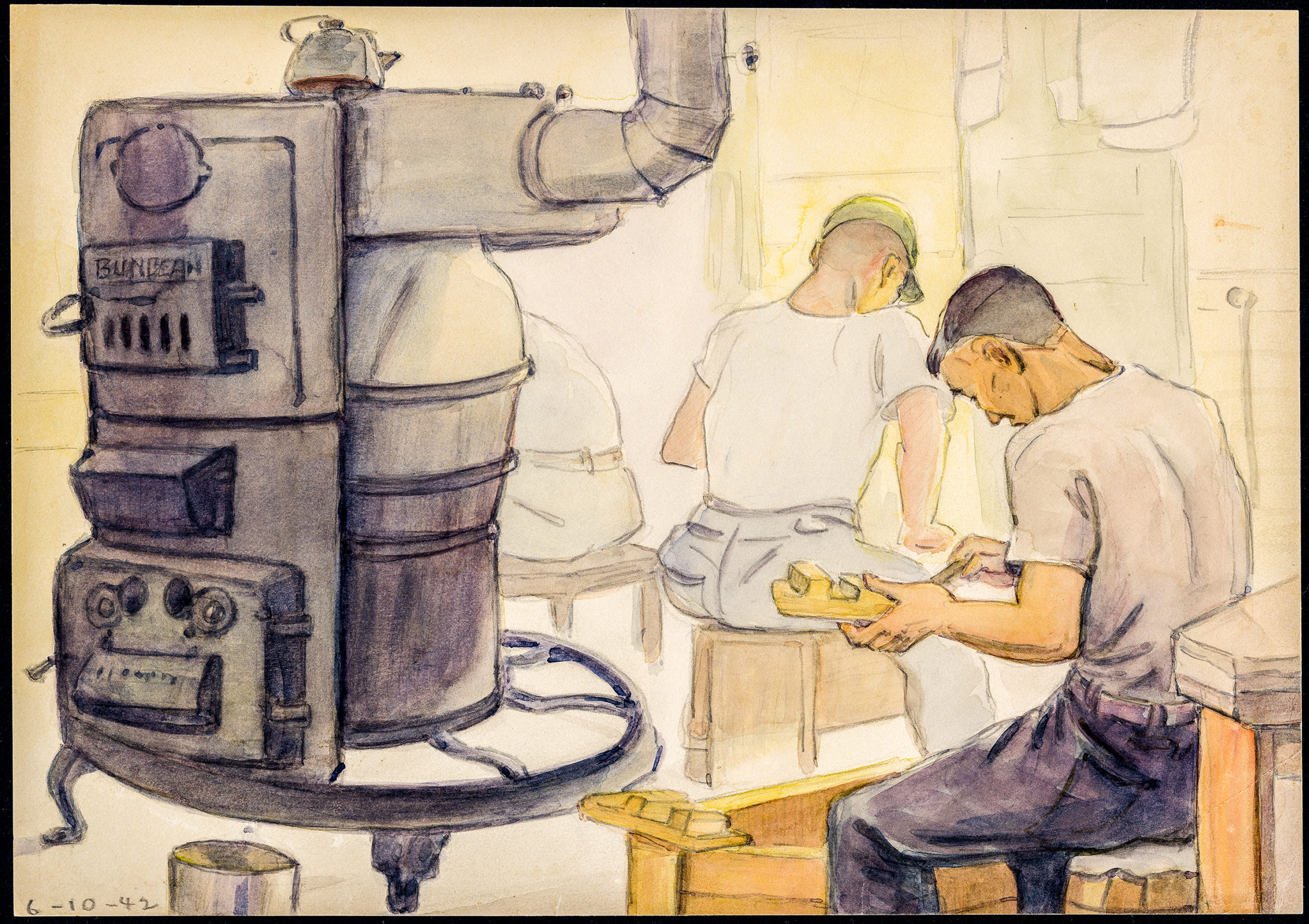

Soon after the camps opened, everyone seemed to be wearing geta.

At Puyallup, Washington, 58-year-old Toyonosuke Fujikado turned his barrack room into a workshop and made 700 geta of different sizes, which he gave away.7

“All of us felt a closeness because we were wearing geta,” wrote the poet Bunichi Kagawa, in 1945.8 Their clacking sound could be heard all around Manzanar (see video).

The tall sandals were a practical solution to the muddy terrain of the camps and the unsanitary conditions of the group toilets and shower rooms.

For people who had little or no prison income, regular shoes were a luxury and geta were available and easy to maintain. “We wanted to protect our leather shoes,” explains Flora Ninomiya, 83, who was seven when she was exiled to Colorado from Richmond, California.

Geta also became an unexpected symbol of “ethnic intensification” during a period of racial stress.

At a time when Japanese Americans were reviled because of their race, the ethnic footwear linked the generations.

“A Jap is a Jap,” General DeWitt famously had said. Wearing geta seemed to subvert the racism into an expression of creativity, pride and defiance. For the immigrants, especially, geta must have felt like the fashion equivalent of comfort food.

Geta sprouted on friendship pins and some were even turned into precarious foot-high platforms, according to Miné Okubo.

The sandals were carved from a wooden block with two stilt-like supports called “teeth” (歯 ha) that elevate the foot.

Unlike rubber flip flops, there is no right or left side to geta. The strap that holds the sandal on the foot is pulled through three holes drilled in the wood.

When a weathered geta with multiple holes was found at the Amache camp in Colorado, archaeologists were initially stymied, but survivors recognized the form.

After two years, reunited in Texas

After two years, Jingo was finally reunited with Kiwa and the boys in Texas, at the Crystal City Internment Camp. Many families were reunited there with the expectation of eventual deportation to Japan. When Japan surrendered and the war ended, Jingo, Kiwa and the four boys applied for “non-repatriation” in August, 1945, to remain in the U.S., but their application was rejected.

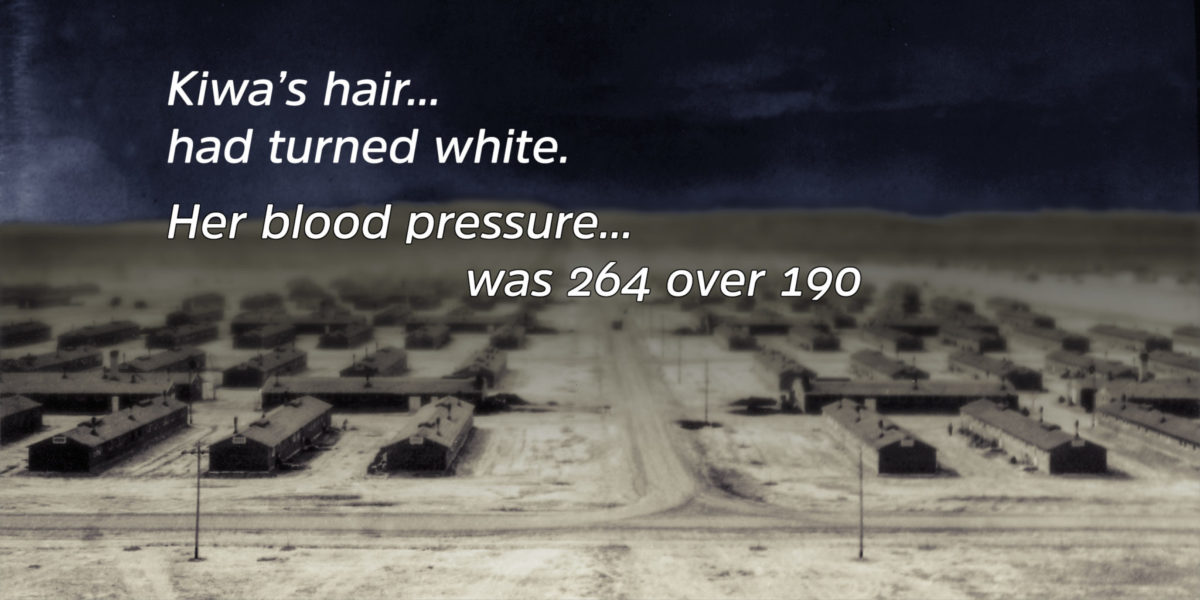

Kiwa’s hair was jet black in 1942 when she entered the camps but it had turned white by 1945, and her heart condition had worsened. Two months after the applications were rejected, she died of heart failure. Her blood pressure was recorded at 264 over 190, according to the government death report. Kiwa was 50 years old.

Photo collage by David Izu.

Not long after Kiwa died, Jingo’s order of alien enemy internment was vacated and he and the boys were released from Crystal City. They finally regained their freedom in 1946, and moved to Santa Barbara to be near Jingo’s adult daughter, Reiko, and her husband, Caesar Uyesaka, who had been incarcerated during the war at Poston, Arizona.

Jingo and Kiwa’s oldest son, Kenji, had been transferred from Topaz to the Tule Lake Segregation Center for registering his dissent on a loyalty questionnaire. In all, Takeuchi family members had been dispersed to seven different camps over the course of five years: Santa Fe, Lordsburg, Tanforan, Topaz, Poston, Tule Lake and Crystal City.

A home in the Smithsonian

In adulthood, Goro married, had four children and ran two gas stations in Santa Barbara with Mamoru. After he died in 2015, Goro’s son, Michael, began to go through his father’s belongings.

His father had saved everything. “There were Tupperware 40 or 50 years old. Dishes. Cool Whip containers…camping equipment from the 1950s.” On a shelf behind a glass dish, “we came across the geta…that his father made for him.”

Michael set aside his father’s sandals but was unsure what to do with them until he attended a reunion of Crystal City survivors in Las Vegas and met Noriko Sanefuji, a curator at the Smithsonian museum. He offered to donate them and they were accepted.

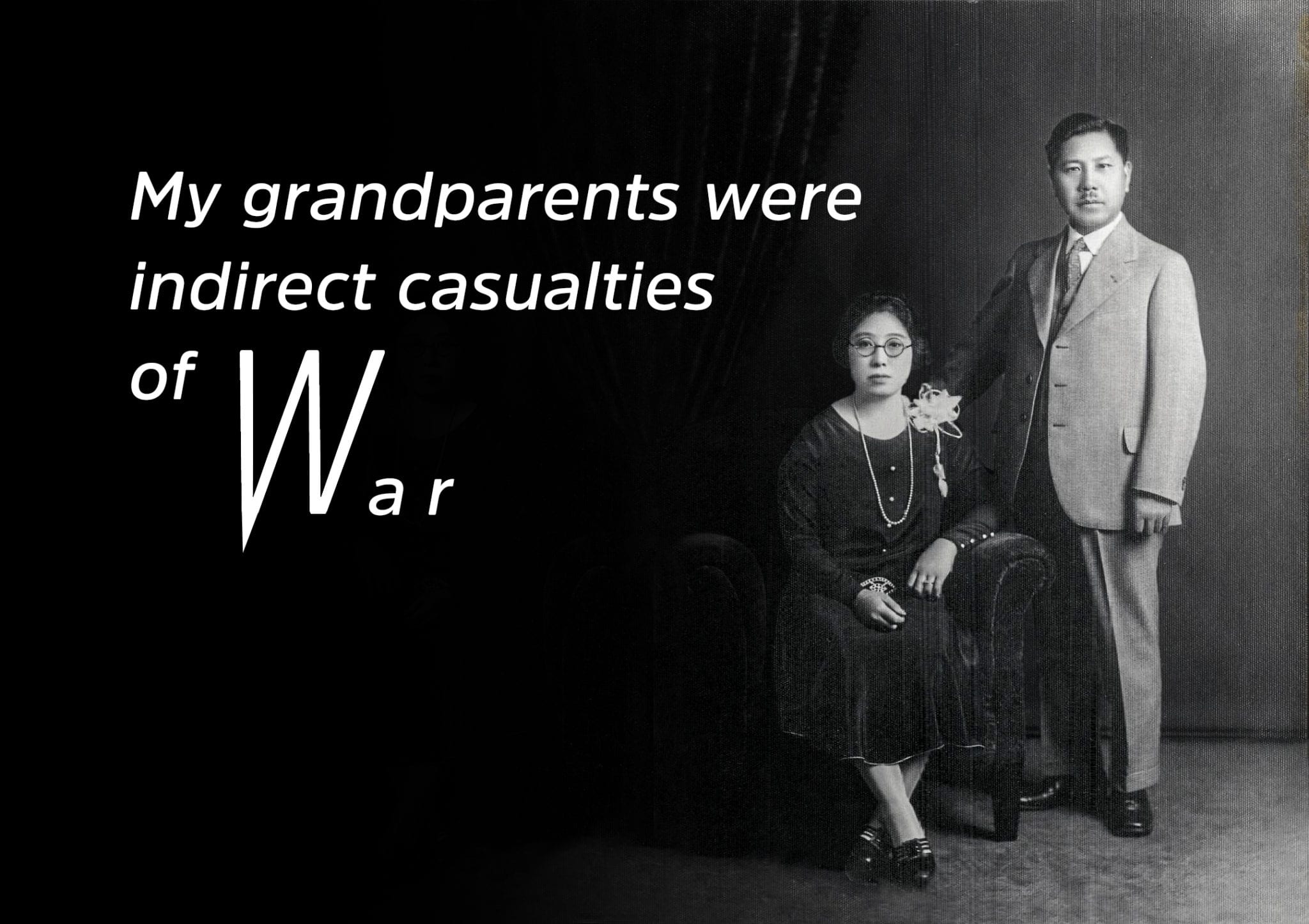

“My grandparents were indirect casualties of war,” Michael said. The Smithsonian was preparing an anniversary exhibition in which the geta could help people remember the family’s suffering and sacrifices.

Besides, Goro had once visited the Smithsonian and “although he was never one to visit museums,” he always talked about it, Michael said.

The wartime incarceration left a difficult legacy for the Takeuchi family. Years of separation and trauma may have contributed to bouts of physical abuse and alcoholism that occurred after the war was over.

The wooden sandals thus embody a complicated and entangled set of memories. For Michael, they are like a three-dimensional postcard on which Jingo seems to be saying to his family, “Wish you were here.” The geta also symbolize Jingo’s love of his native land and the U.S., his adopted country.

When the naturalization laws changed, Jingo applied to became a U.S. citizen. “I believe he wanted to prove that he wasn’t a disloyal person to the U.S.,” Michael said. Jingo received his U.S. citizenship papers at the end of 1954. Two months later, he died from a blood clot.

Michael thinks that all four of the boys must have received their own pair of geta from Jingo, although no more have been found. For now, the sweet mouse that was born in a desert prison walks alone, bearing the fading memories of a family’s confinement.

| Takeuchi Geta | |

|---|---|

| dimensions | 6 1/2 in x 3 1/2 in x 2 in |

| material | wood, rubber, cotton, silk, paint |

| date | c 1943-1943 |

| site of creation | Santa Fe, New Mexico |

| collection | Division of Political and Military History, Smithsonian National Museum of American History |

| photo right | Noriko Sanefuji, Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Photo by Mandy Yu. |

Credits

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Michael Takeuchi, David Izu, the National Archives and Records Administration

Special thanks to:

Michael Takeuchi, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Noriko Sanefuji, Valeska Hilbig, Mandy Yu, Sharon Imura Handa, Amache Museum, John Hopper, Anne Amati, Tooru Nakahira, Flora Ninomiya, Japanese American Archival Collection, Special Collections and University Archives, California State University, Sacramento, Julie Thomas, National Japanese American Historical Society, Rosalyn Tonai, Max Nihei, Densho, Jean Sogioka La Spina, Patti Hirahara, George and Frank C. Hirahara Collection, Washington State University Libraries, Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Delphine Hirasuna, Gail Nanbu, Helene Mihara, Sam Mihara, Manzanar National Historic Site, Alisa Lynch, Bernadette Johnson, Japanese American Service Committee, Ryan Yokota, Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, Dakota Russell, Dr. Junko Kobayashi.

Supported in part by the National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program