It was Sunday, July 4, 1943.

Four-year-old Paul Tomita was experiencing Independence Day, not with sparklers and parades, but by getting his right index finger inked.

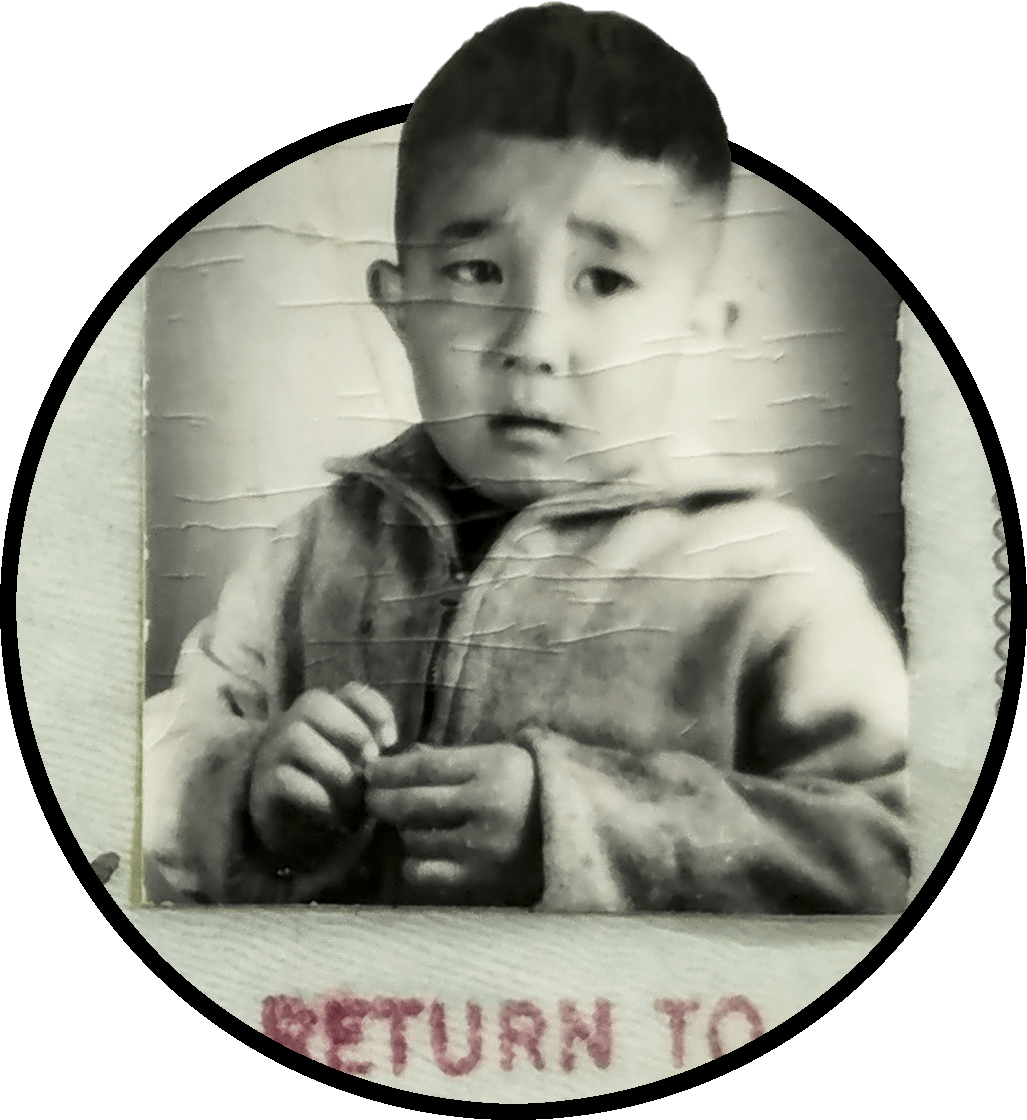

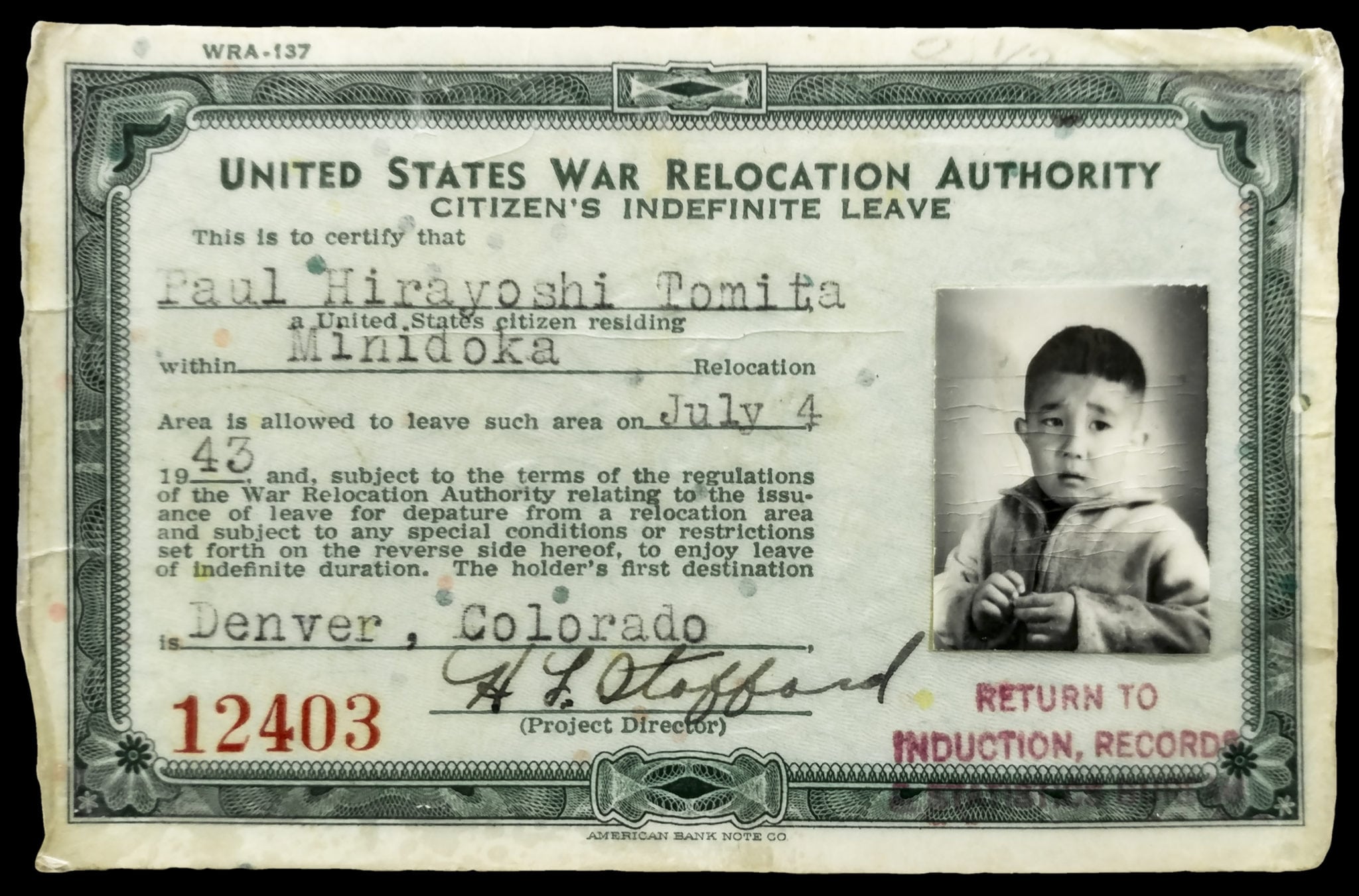

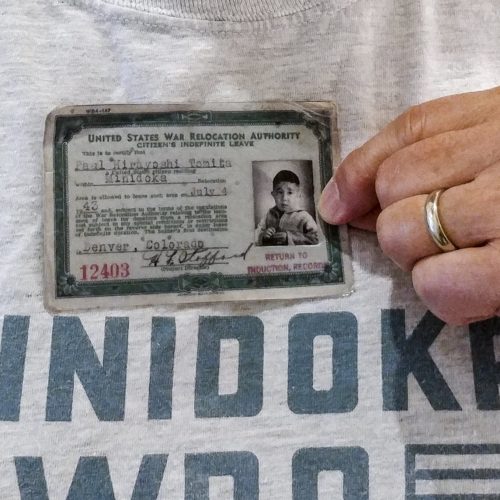

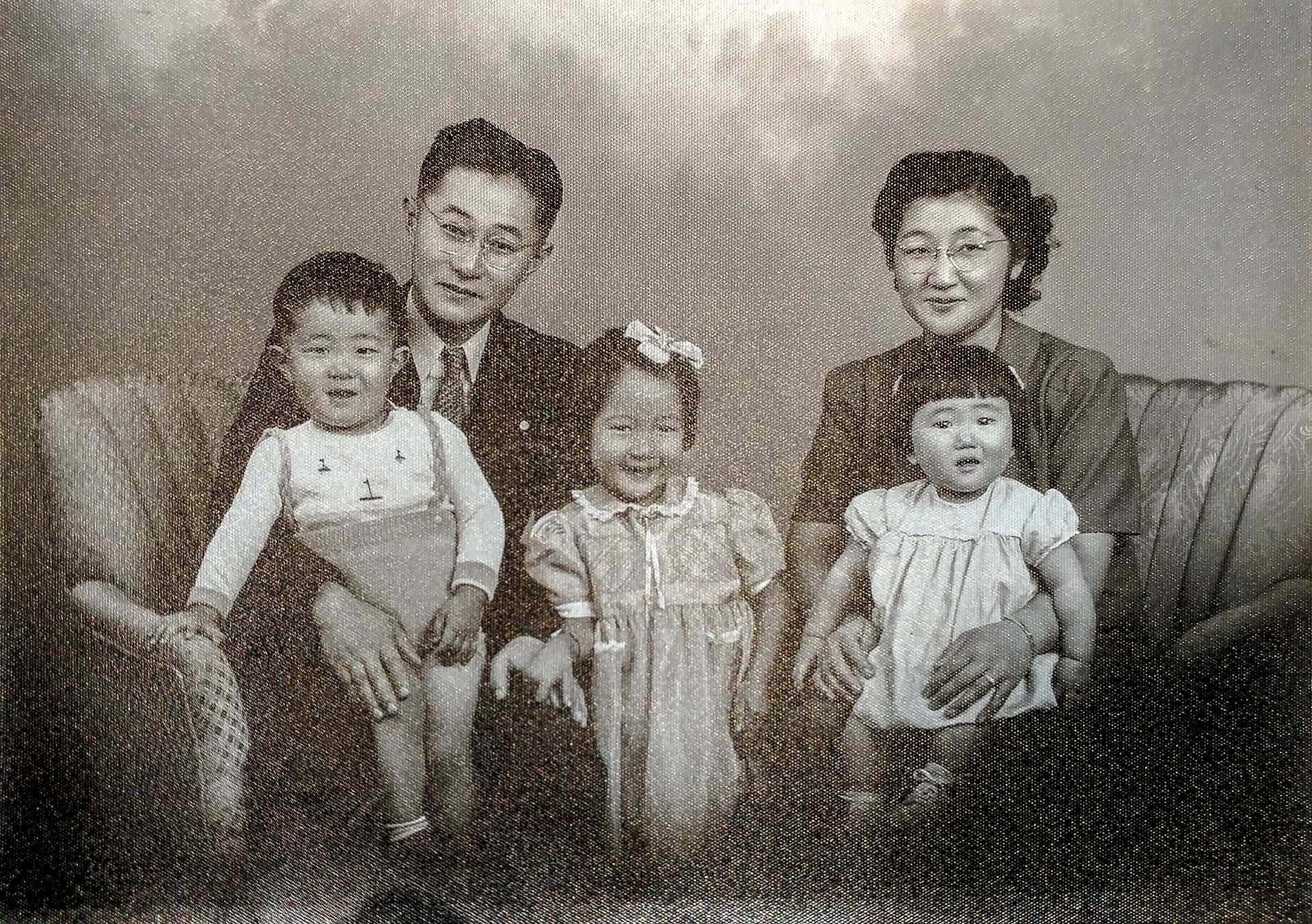

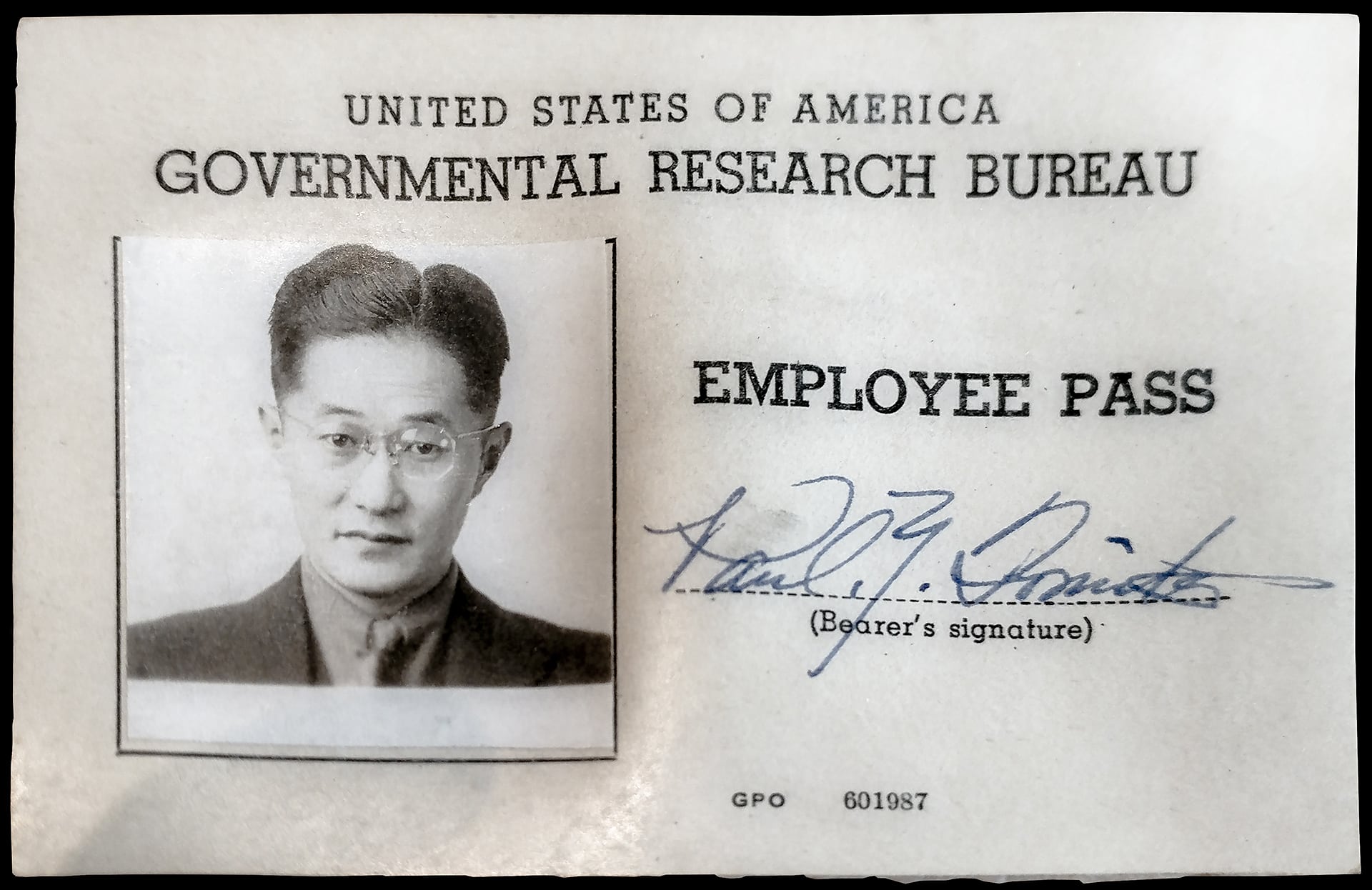

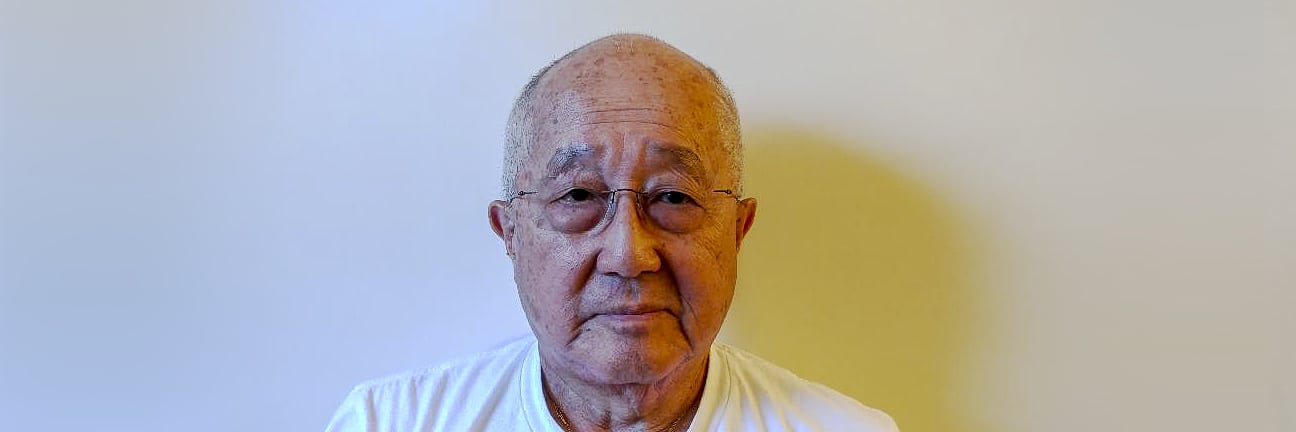

On that day, he was fingerprinted and photographed for a mint-green exit card that certified he was not a risk to national security. In the photo, Paul looks anxious and forlorn. “My parents are nervous and stressed out,” Paul, 79, says now, as he views the card. “And I know something is wrong.”

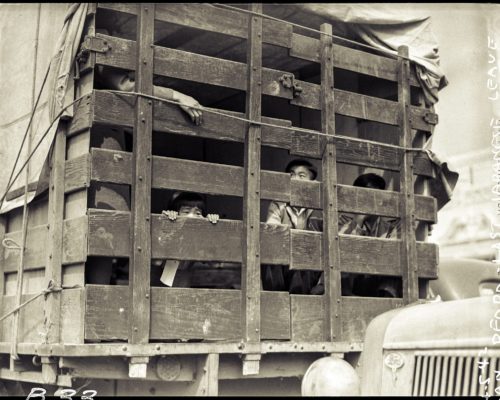

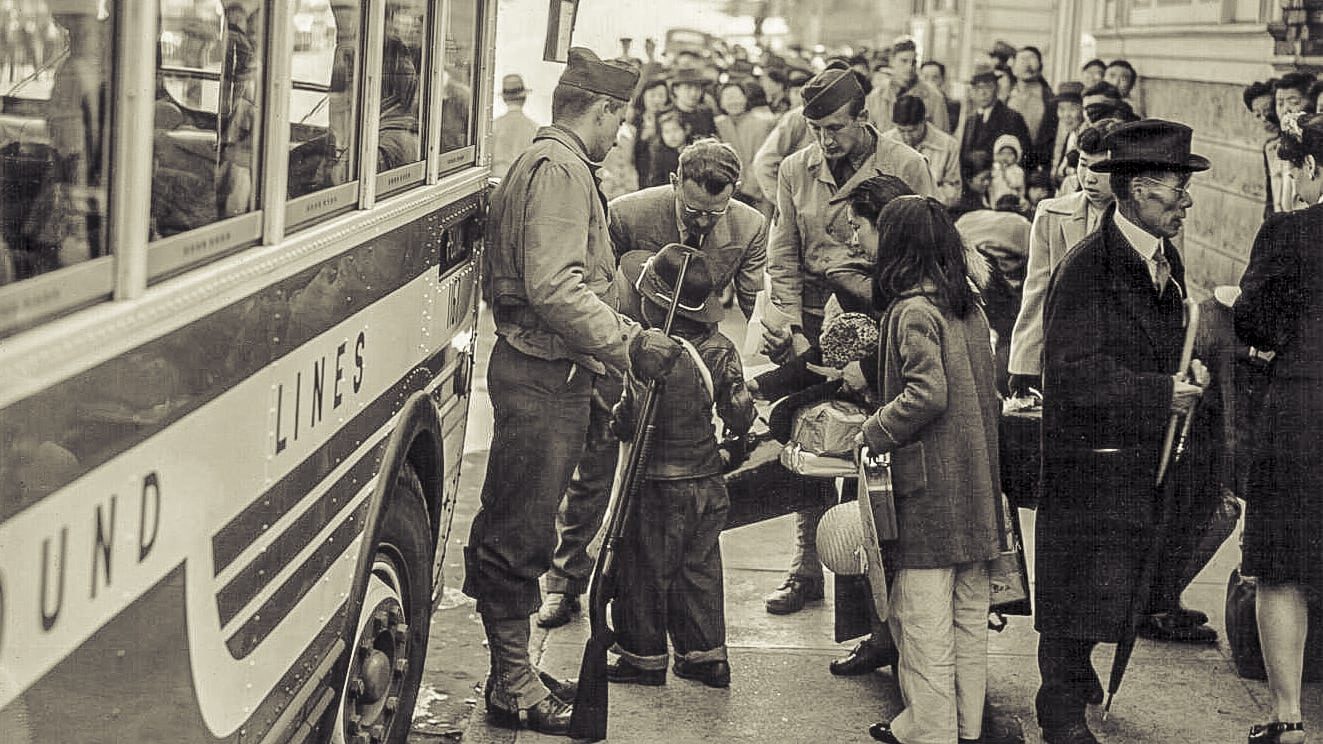

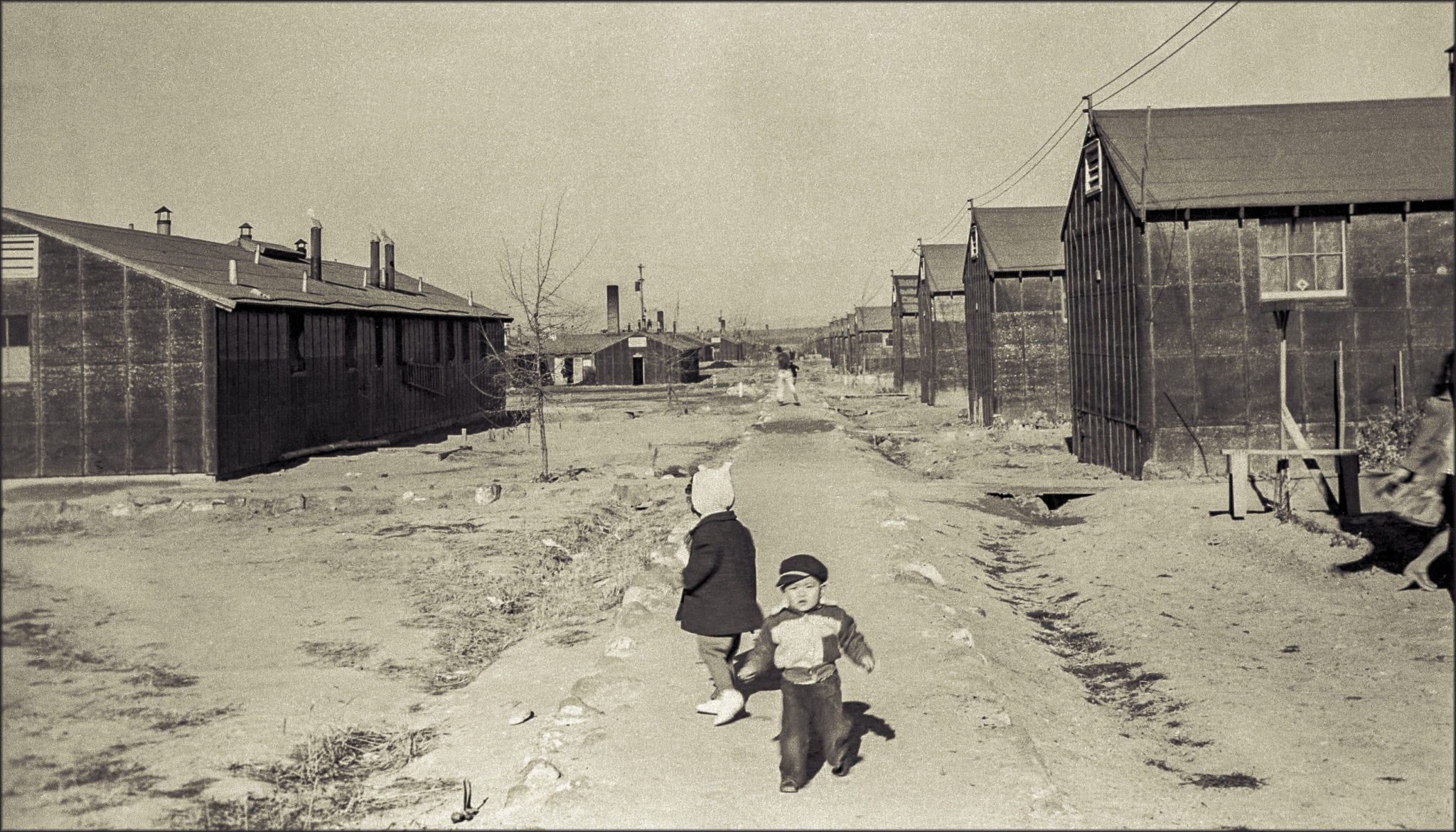

His family had spent 14 months in captivity in two U.S. government concentration camps. After the U.S. declared war on Japan, the Tomita family had been forced from their Seattle home to a converted fairgrounds in Puyallup, WA, and then moved under armed guard with some 8,000 other innocent civilians to the Minidoka prison camp in southern Idaho.

Guilty only of looking like the enemy, the Washington natives found themselves crammed into one room in Minidoka’s Block 12-5-E. But, encouraged by the government to leave the camp and “resettle” in areas outside the prohibited West Coast military zones, Paul’s father was able to secure a job on the East Coast.

Paul’s parents signed loyalty documents and passed stringent security investigations. The family was now cleared to leave, first for Denver and then to Washington, D.C.

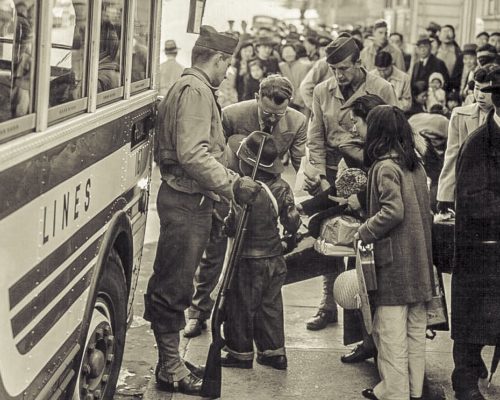

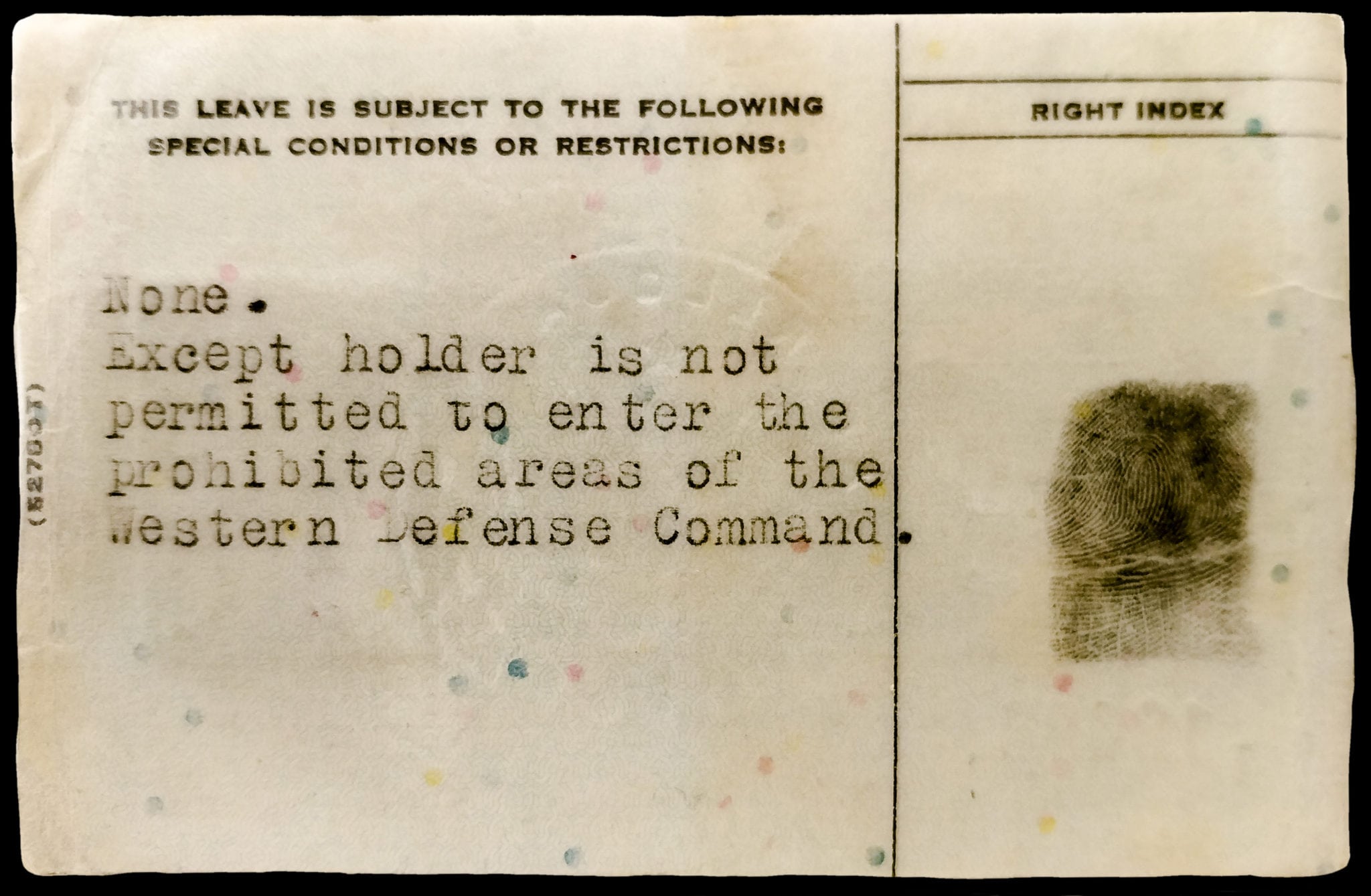

But there was one last step before their release: receiving the official leave card. Each family member was photographed and fingerprinted, even Paul’s sister, Emiko, who was two years old.

The exit cards were to be carried at all times. Released prisoners were still under the control of the War Relocation Authority, which operated the camps and could revoke the leave for violation of conditions. So the cards served as a type of parole card. Needing to carry such permits was yet another humiliation. And it felt like the children were being criminalized.

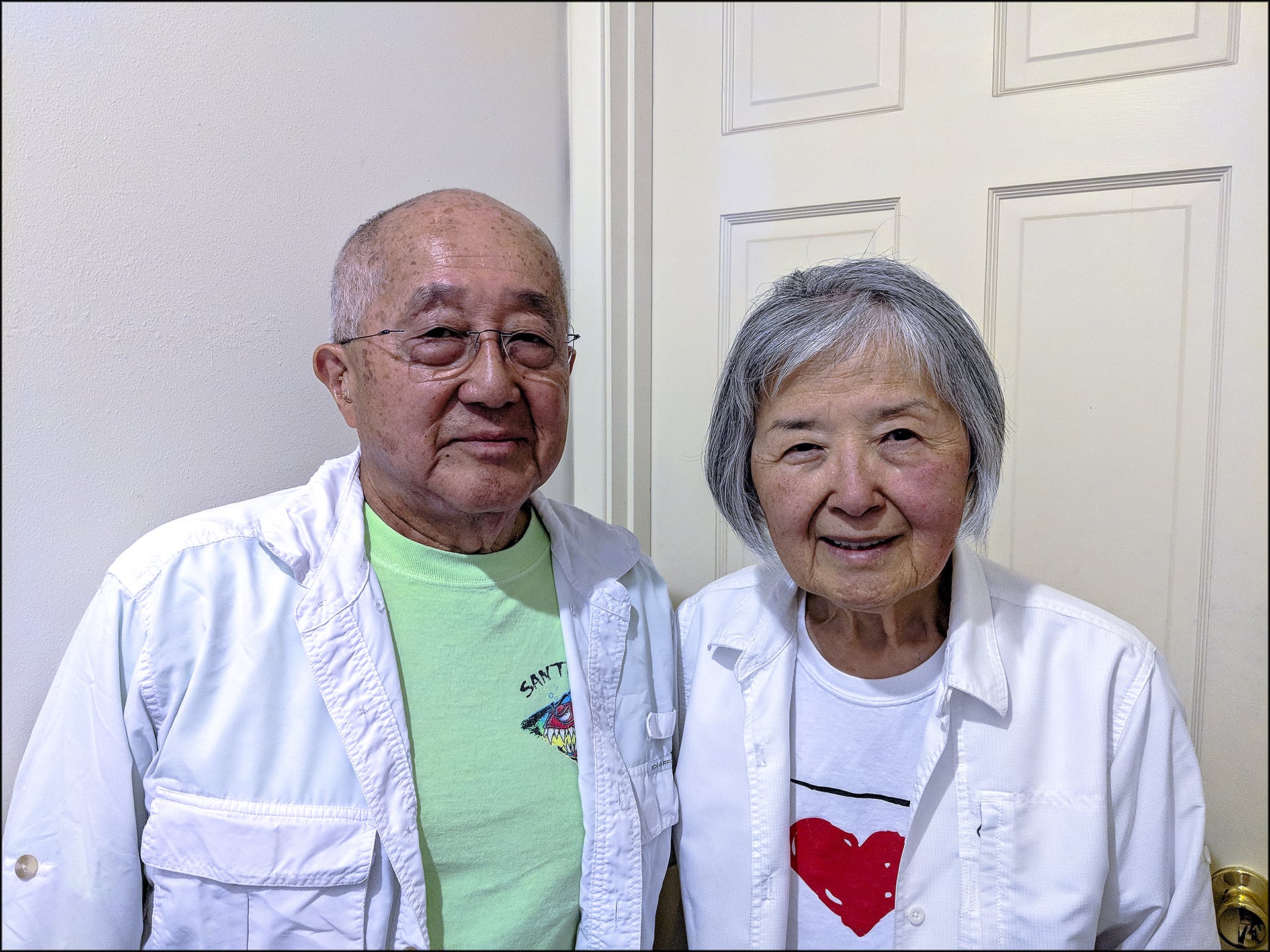

Many Fourth of July holidays have come and gone for Paul. He now values the card as evidence of a time that should not be forgotten but also as a sign that history repeats itself.

“I felt sick,” he said, when he learned of infants and children being torn from their parents at the southern border and incarcerated in metal cages, tent cities and converted box stores. “We have really hit the bottom of the barrel to even think about that,” he said.

“Same thing, different era.”

His thoughts were echoed by former First Lady Laura Bush, who described the “warehousing” of migrant children at the border as “eerily reminiscent of the internment camps for U.S. citizens and noncitizens of Japanese descent during World War II, now considered to have been one of the most shameful episodes in U.S. history.”

Paul’s mother, Bessie Tomita, was 29 at the time of the family’s release from Minidoka. She defied government instructions and kept the cards. When the children reached high school age, she gave the leave cards to Paul, Deanna and Emiko to remind them of a history that they had lived but hadn’t learned about in school.

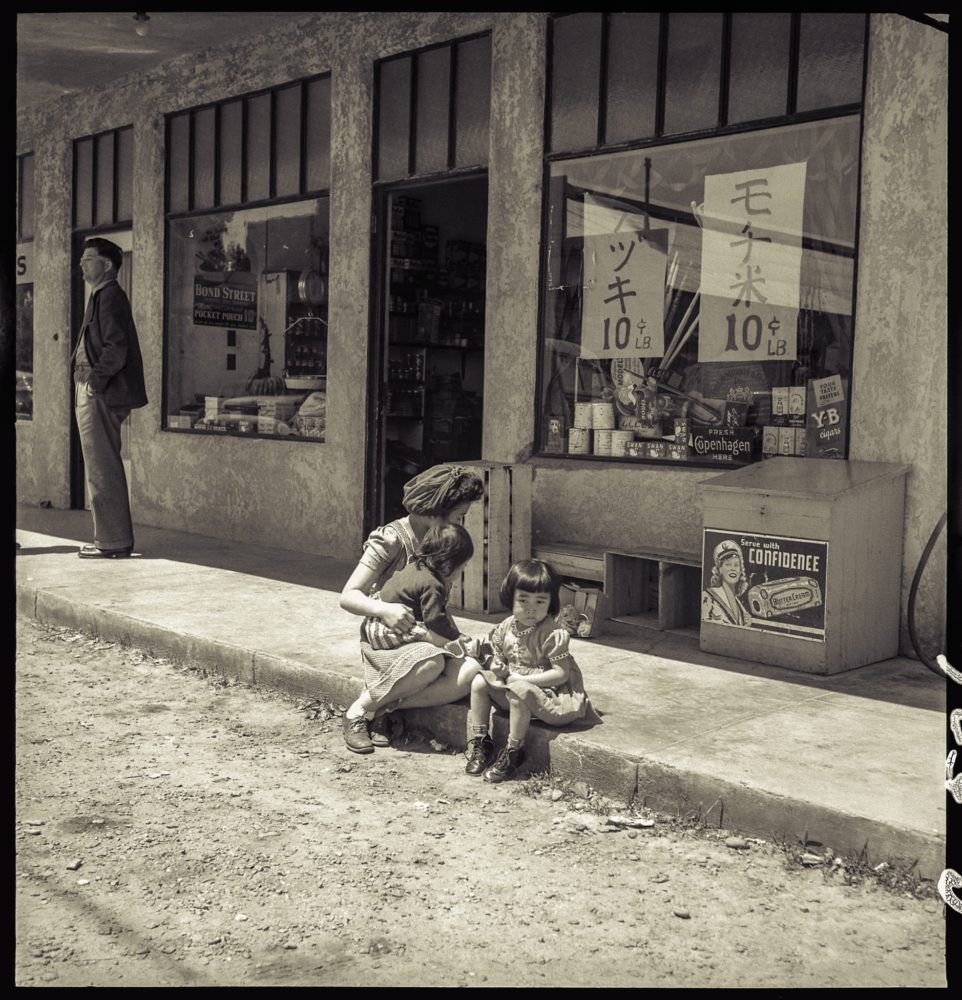

Racial hatred, political expediency, greed and groundless fears of espionage led to the mass expulsion of 110,000 Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast after President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February, 1942.

More than 40,000 children were imprisoned that spring, one third of the total. Even babies and children in orphanages, including those of mixed race, were rounded up.1 Activist Raymond Okamura later regretted that no one had thought to file a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of a child, to challenge the lack of due process.2

A majority of the imprisoned population, in fact, had exited the camps before the last one closed in 1946. Soon after the first camps opened in 1942, the government began developing policies to release select groups of approved citizens and immigrants back into society after intensive vetting. There was concern that innocent captives would turn bitter and disloyal if kept under armed guard for too long. It also was expensive to operate a string of federal concentration camps whose population would eventually swell to 120,000.

Various types of civilian leave were gradually permitted: short-term leave to fill the labor gap on farms, permit to exit to attend colleges that would accept American Japanese students, and “indefinite leave” for those who had obtained proof of a job and a place to stay in a community that would accept them.5 In addition, military clearance was issued to those entering the U.S. Army and other branches of service.

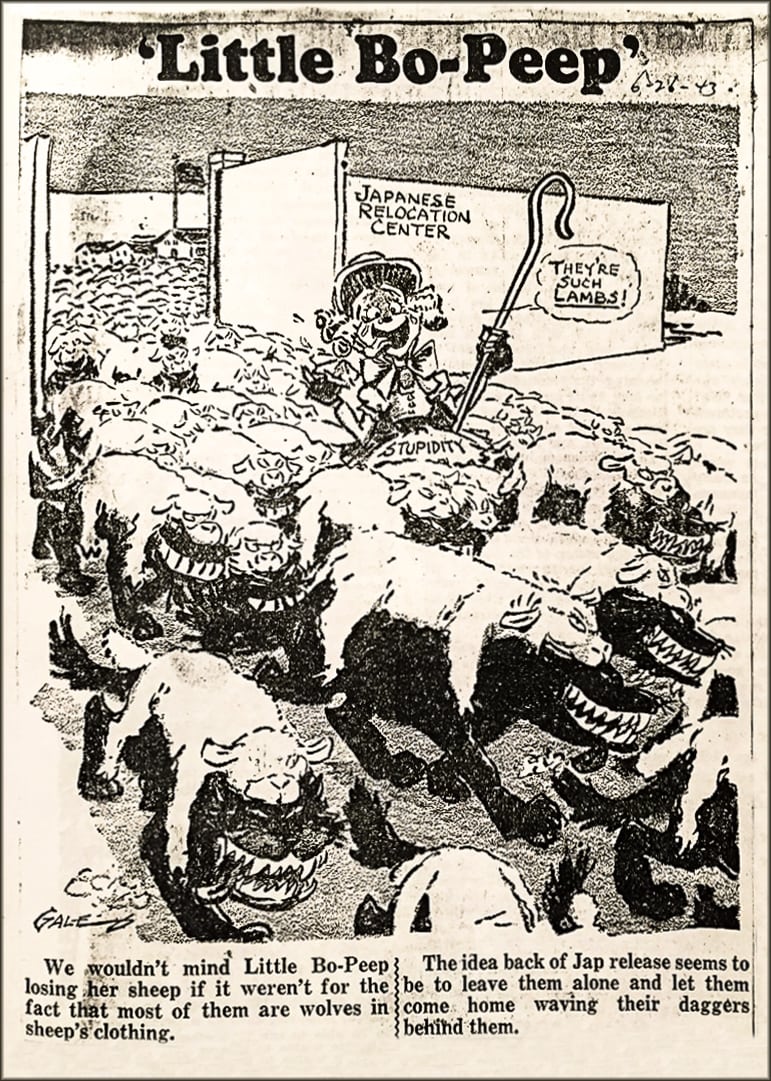

Having incited fear by exiling an entire racial group under the guise of “military necessity,” the government now had to convince the public that it was safe to release these so-called security risks back into society. “Wolves in sheep’s clothing” is how one editorial cartoonist depicted the newly released.

Such social conditions may partly explain why the camp leave procedure was documented by government photographers. The public needed to be reassured that inmates were being properly processed before their release.6

The original leave permit was a one-page, typed document. In March, 1943, the wallet-sized card replaced it, with the addition of a photo and fingerprint.7

Paul and Bessie Tomita, the parents of Paul Jr., were born in Seattle and Thomas, WA, respectively. The death of Paul’s immigrant father, Kannosuke, in 1920, in a motorcycle accident, left his widow, Shigeno, with three sons. She returned to her native Hiroshima to raise the children. The three American boys attended school there and became fluent in Japanese.

Shigeno and her boys returned to Seattle in the mid-1920s. Her son, Paul, and his younger brother eventually opened a printing company and typeset menus and material in Chinese, Japanese and English for restaurants and shops.

The exclusion orders came in 1942 and the Tomitas became family No. 11940. Shigeno joined Paul’s family in the barracks. But when her son and the family were released, she stayed behind, moving into a different barrack with a single woman. She lived in confinement for two more years.

Paul Sr. passed the highest level of clearance in order to take a job with the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor to the CIA. “From suspected spy to real U.S. spy,” Paul observes now.

His father’s fluency in Japanese helped the war effort. He was assigned to translate U.S. propaganda material into Japanese and typeset the leaflets in a print shop at Georgetown University. The flyers were dropped on enemy Japanese soldiers in the South Pacific, urging them to surrender.

After the war ended, the Tomitas returned to Seattle, among the 60 percent of Japanese Americans who returned to the West Coast. One of the relatives didn’t return. He went to New York and didn’t come back to the West Coast for 50 years, he was so angry, Paul said.

The Tomitas’ neighbors in Seattle had stored the family’s printing machines in their basement, a kindness that enabled Paul Sr. and his brother Theodore to restart the typesetting business after the war ended.

Theirs was an unusual case. “Many people who stored their belongings in commercial places came back to find that everything had been looted and they had no recourse but to start all over from nothing,” Paul said. “We Japanese Americans weren’t in a position to sue.”

Paul eventually became a counselor, a decision he attributes partly to the childhood trauma of incarceration.“Even to this day, here in America, I’m always on guard.”

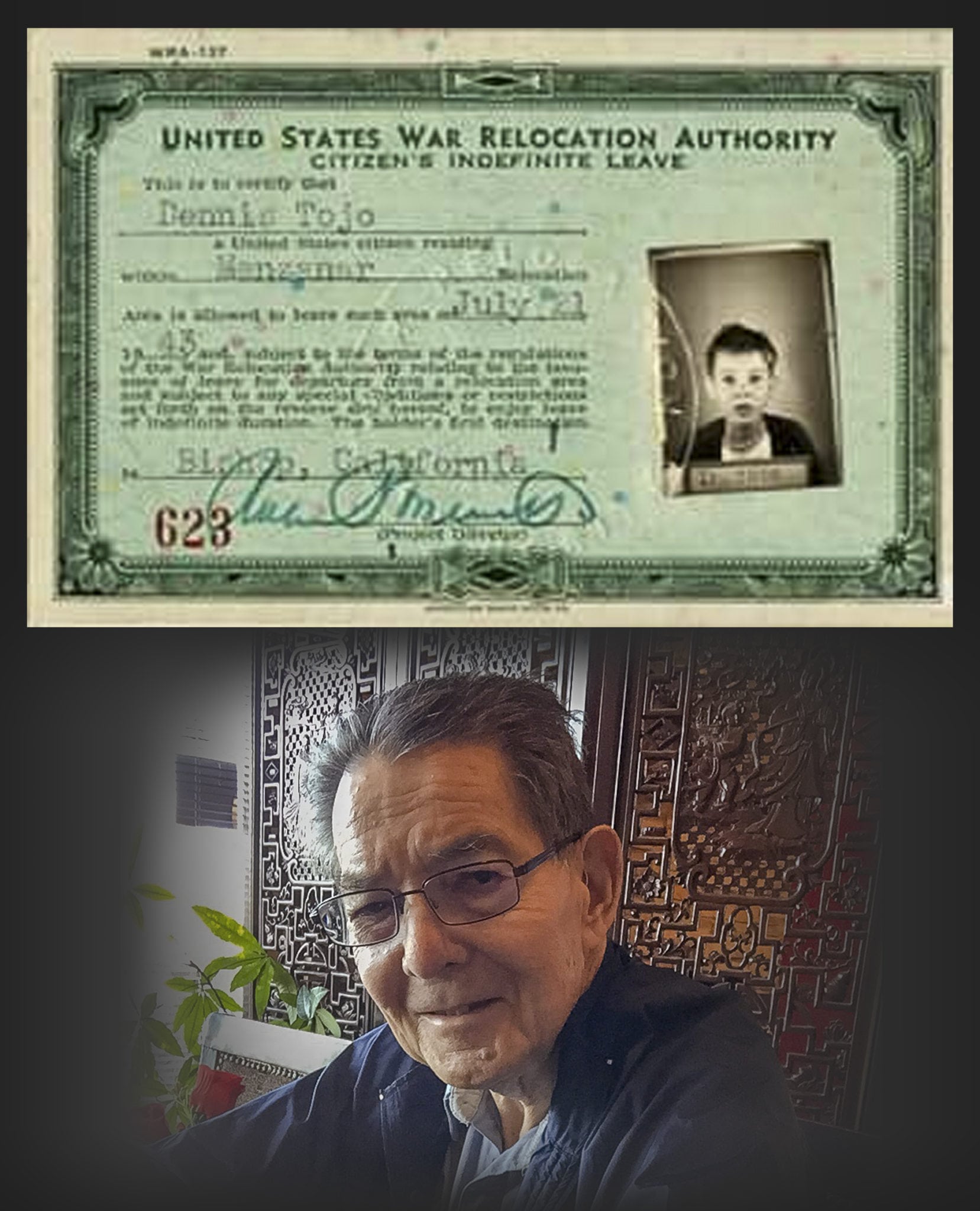

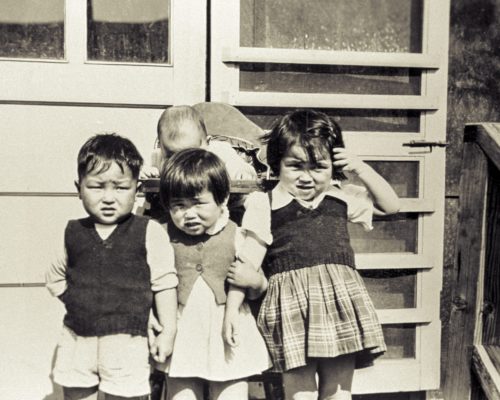

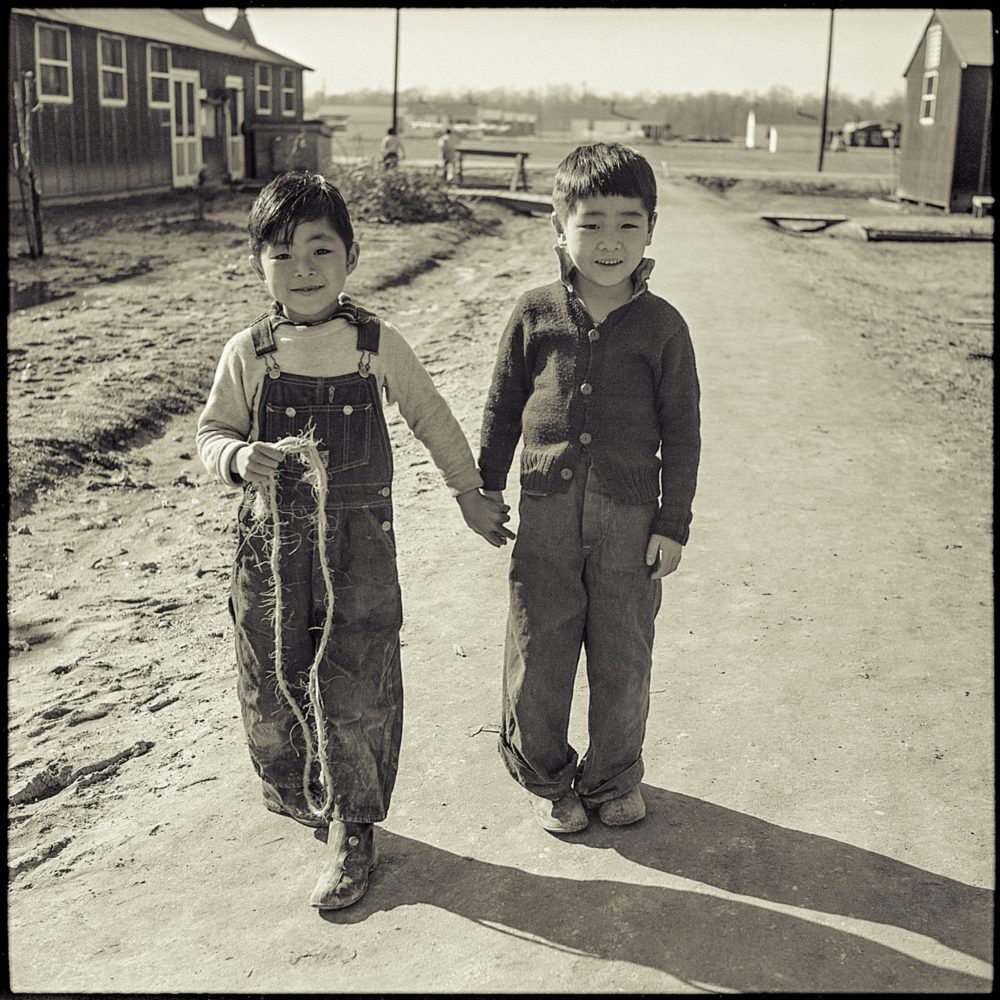

Confinement at a tender age

Dennis Tojo Bambauer, 8 years old

Dennis Tojo learned for the first time that he was part Japanese when he was taken by armed guard to the Manzanar prison camp from an orphanage in Los Angeles. The U.S. Army had identified children who had partial Japanese ancestry. He left Manzanar when a local family, the Bambauers of Bishop, CA, adopted him.

Manzanar, California

“When I got ready to leave camp,… I was told that I had to stop by the military compound before I could leave. And the purpose for my stop was so that I could be fingerprinted, and I’m six, seven years old and I remember the soldier saying, ‘This is in case you do anything bad, we’ll be able to catch you.’

“That was a traumatic experience for me. And I’m sure that the soldier didn’t mean anything of that but it really knocked me for a loop. That was really sad. Didn’t make me angry because at that age you don’t get angry, you get scared. So it just made me even more scared.

“At the same time they gave us a green card and that same person who fingerprinted me and telling me he was going to catch me, also told me that I had to wear that card because I was being allowed to leave the camp….I think the rules were that you had to have it in your possession but for a six-year-old it’d be around your neck, and that I could never go without it. Which when you add that to the fingerprinting just compounds the fear even more.”

Bambauer leave card courtesy Manzanar National Historic Site and Dennis Tojo Bambauer. Photo collage by David Izu. Dennis’ testimony from an oral history courtesy of Manzanar National Historic Site and Densho.

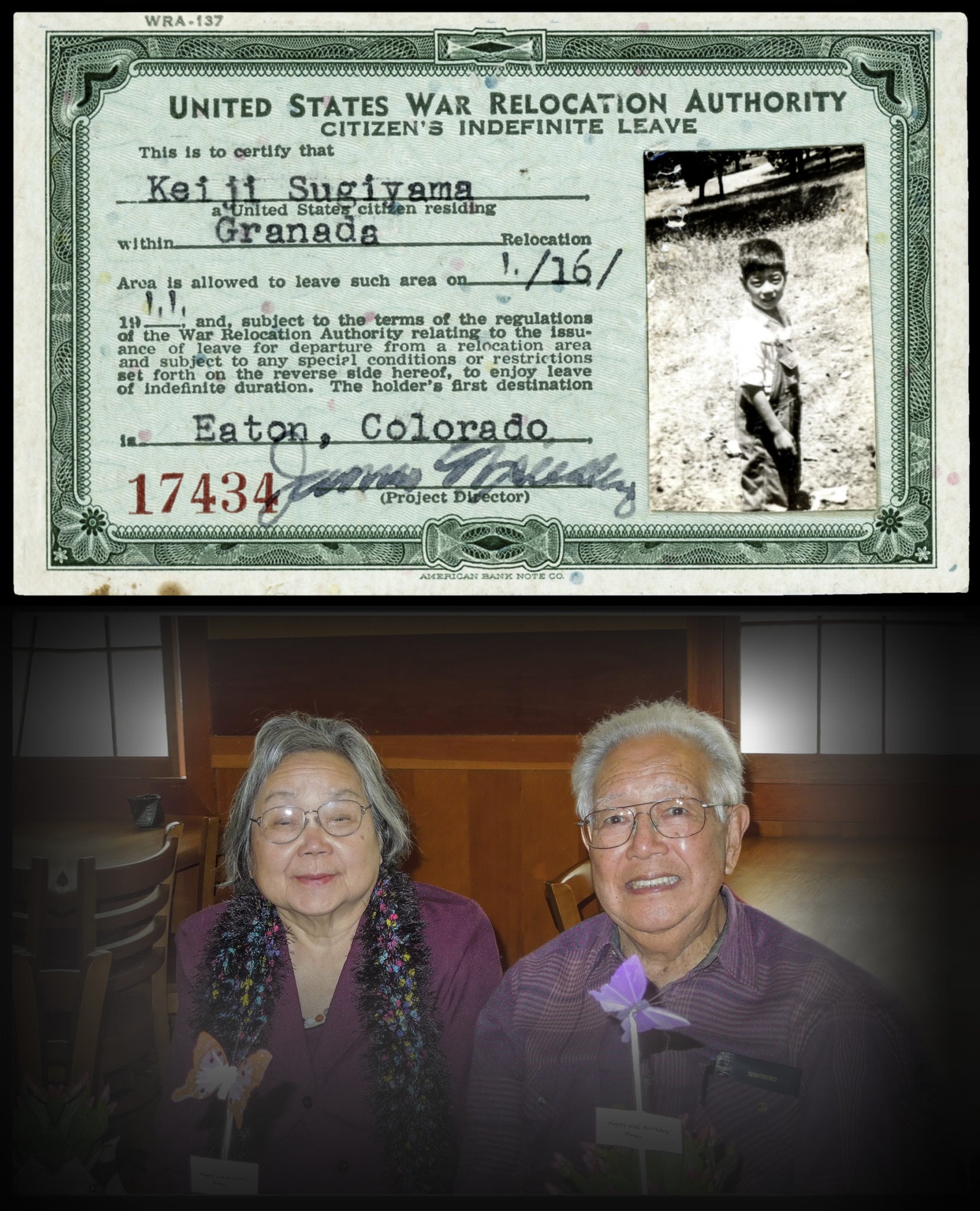

Keiji Sugiyama, 12 years old

Amache (Granada), Colorado

“I was 10 years old when they notified us we had to report to a certain area. We were moved to Merced and put into a temporary camp.

“They notified us that we had two weeks to get ready. We had to get rid of the farm equipment and everything. So what my father did was sell some of the apple picking equipment for hardly anything. At that time there were eight children and my mother and father, 10 of us.

“We were housed in tar paper barracks for a year and a half and then the government started to encourage us to move out and make a living in some of the other states. We could move out as long as we never moved back to the West Coast.

“So my brother found a place where we could go north of Denver, a little town called Eaton. This leave card is from that time. We moved there and the family worked on a farm. We helped harvest the crops that the farmers planted like sugar beets. Row crops such as lettuce and onions.

“When we came back to California after the war, we never bothered to go back and find out what we had. We just let it go.”

Leave card from the Sugiyama family collection. Photo of Keiji and wife Hideko courtesy of Keiji Sugiyama. Photo collage by David Izu.

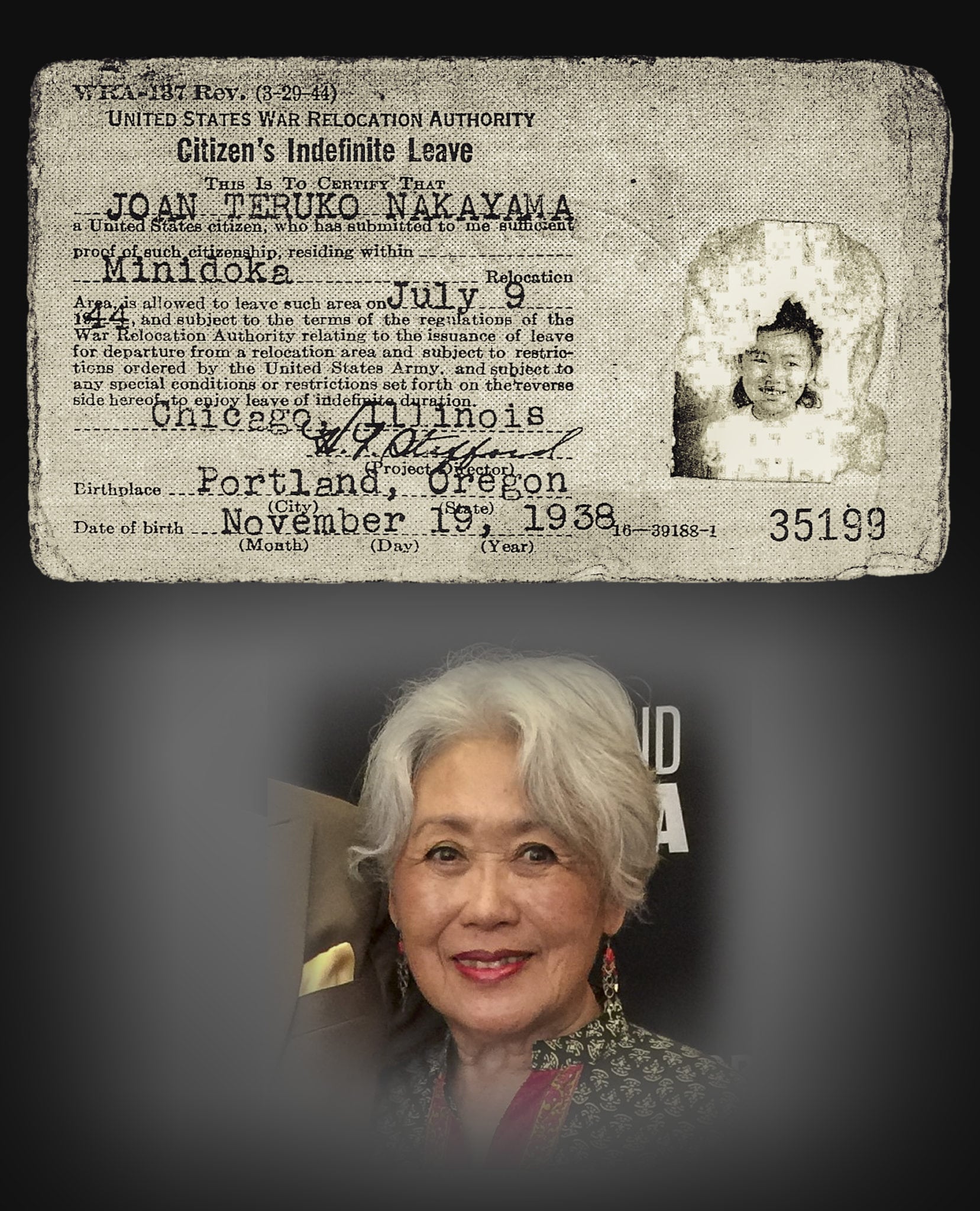

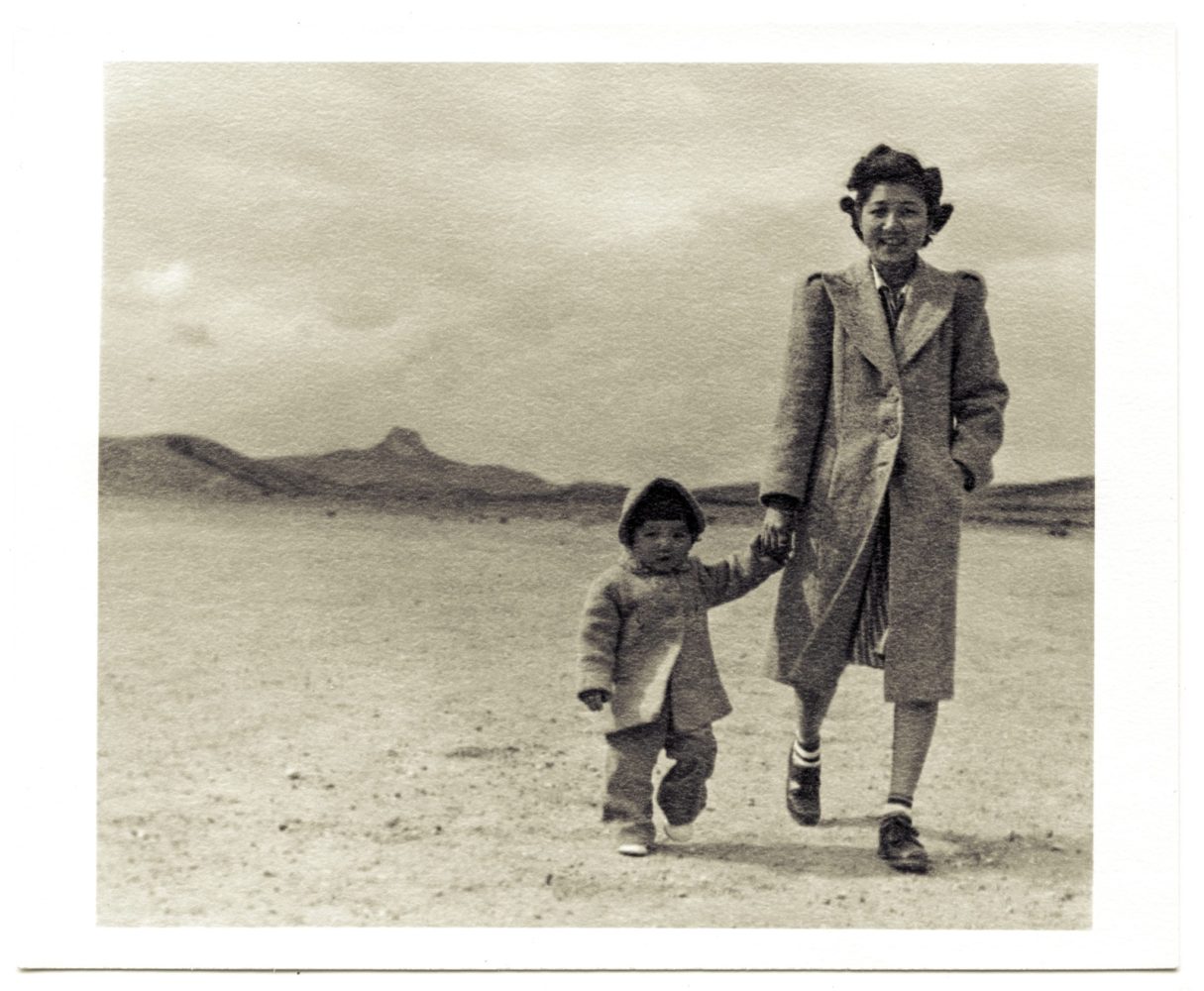

Joni Nakayama (Kimoto), five years old

Minidoka, Idaho

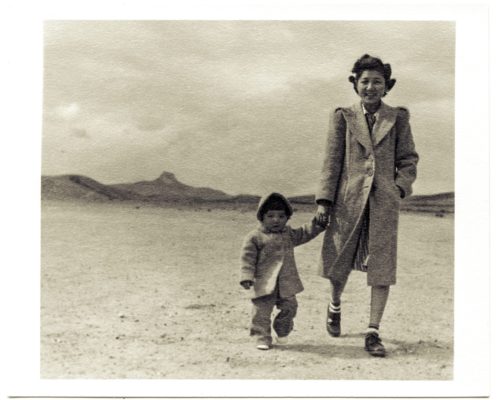

“We traveled by train from Minidoka to Chicago and had these indefinite passes issued to us. It’s ‘indefinite,’ meaning what? You may have to be called back? My mother gave me her card and said, ‘I hung on to this because what if they ask us to go back to camp?’ The war was still on in 1944.

“My father and mother never allowed me to be afraid of anything. As a child, you don’t have that fear. You know this is life and as long as you are with your mom and dad and have some playmates, you’re fine. I felt different when we left camp.

“When I came to the West Coast, my mother had me live with a great aunt in Netarts, Oregon, outside Tillamook. My parents were just starting their lives again and my great aunt didn’t have children. My mother asked, ‘would it be okay if we brought Joni to Netarts and let her go to a small rural school and live at the beach?’ My first day of school the principal put me on the stage and looking back, I don’t think he meant it that way, but it was awful. He said, ‘I want to introduce this little Jap girl,’ and kids came up and touched me and asked me why I looked the way I did.

“It took me a while to adjust to life there. It makes you a stronger person and more appreciative of your own life. As a result of all this, I’m active in other communities like LGBTQ. My husband and I are part of a Muslim education trust, an interfaith group. We have compassion and understanding for marginalized communities.”

Leave card and photo courtesy of Joni Kimoto. Photo collage by David Izu.

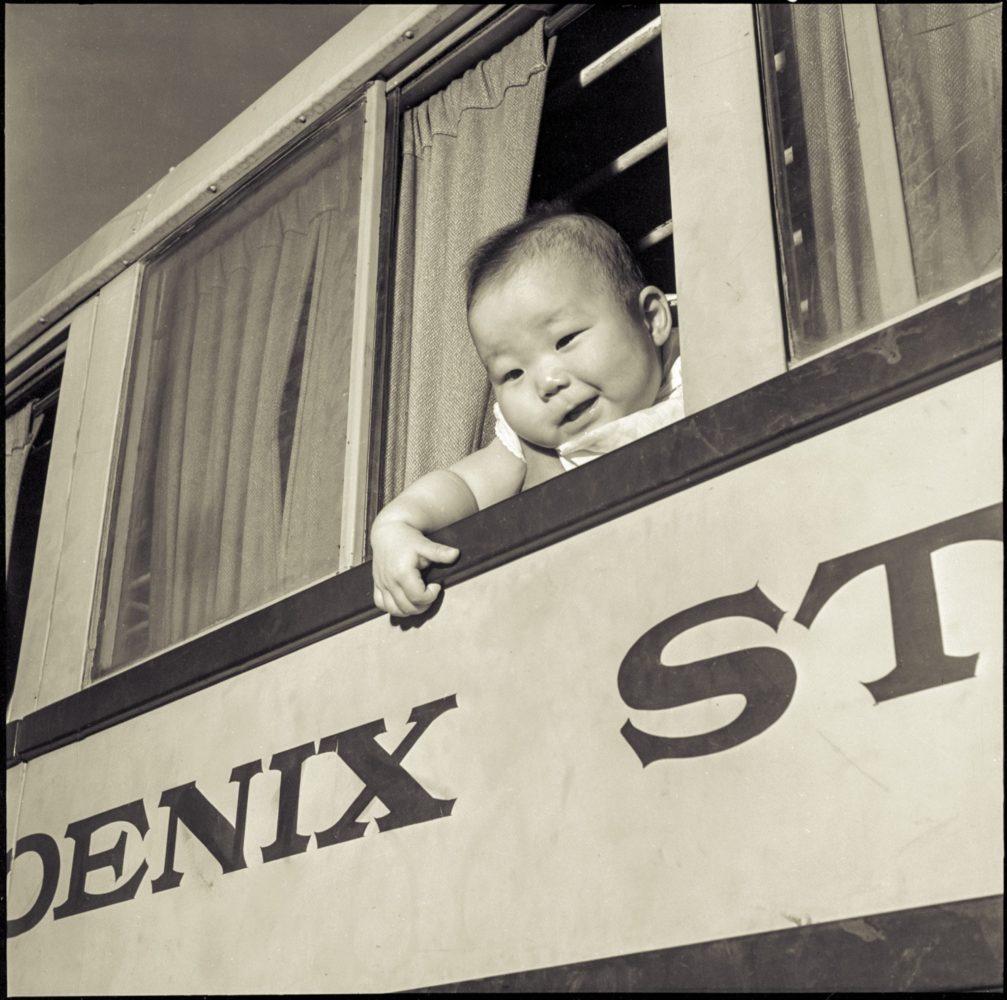

Terry K. Takeda, one year old

Heart Mountain, Wyoming

“This card means a lot to me. I want to keep it till I die to make me realize how lucky I am now to be blessed each day.

“For me, being able to leave camp early was a lucky break since I was able to have my freedom and enjoy a relatively normal life at the age of one year old.

“I don’t remember much since I was born at White Memorial Hospital in Los Angeles and then my parents and I were sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Center. My father was an editor at the Los Angeles Rafu Shimpo newspaper. It was owned by Mr. Komai. My mother was a milliner making hats and handbags.

“While we were at Heart Mountain, my father gained employment as an instructor at the U.S. Navy Language School in Boulder, Colorado, and he taught Japanese to U.S. military personnel.

“Being an infant then was a blessing. By sharing my story, I hope it can help future generations because children need protection in difficult times.”

Leave card courtesy of Takeda Family Papers, 1938-circa 2012, Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries, Pullman, WA. Photo: Terry K. Takeda held by his mother, Hisako, at Heart Mountain, WY, 1943. Photo collage by David Izu.

Credits

July 4, 2018

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: Indefinite leave card courtesy of Paul Tomita, WRA images of Dianne Oki being photographed and fingerprinted, by Hikaru Iwasaki. Minidoka landscape courtesy of the Mitsuoka family collection.

Special thanks to:

Paul Tomita, Mabel Imai Tomita, Terry K. Takeda, Joni Kimoto, Lynn Fuchigami Parks, Keiji Sugiyama, Marie Sugiyama, Patti Hirahara, Dennis Tojo Bambauer, Sherrill Bambauer, Bernadette Johnson, Alisa Lynch, Manzanar National Historic Site, Densho, Martha Nakagawa, Rafu Shimpo, Keiki Fujita, Trevor Bond, Mark O’English, George and Frank C. Hirahara Photograph Collection of Heart Mountain, Wyoming 1943-1945, Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries, Cheryl Oestreicher, Robert C. Sims Collection on Minidoka and Japanese Americans, Boise State University, Dakota Russell, Heart Mountain Interpretive Center.

Supported in part by The National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program