Whether a signed name is on an item of clothing, a high school yearbook or scribbled on a wall, the signature is a physical and symbolic trace that marks a time and a place. It says, “I was here.”

It was no different for the innocent people who put their names on various objects after being rounded up and imprisoned 76 years ago, but the signed artifacts are so visually compelling that it’s easy to overlook their value as ledgers of social groupings that hold rich geneaological information.1 They are valuable historical evidence.

Signed objects also show how people chose to memorialize their time together during incarceration. Departures, transfers and goodbyes, which were often the reason to collect signatures, started from the day that people were forced from their homes. In addition to signing autograph books, signatures can be found on wood kobu sculptures, baseballs and textiles.

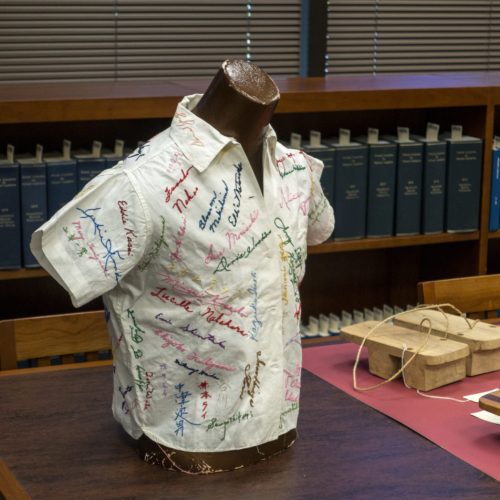

Fusaye’s signed shirt

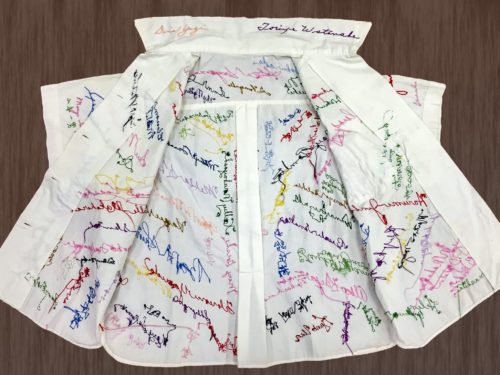

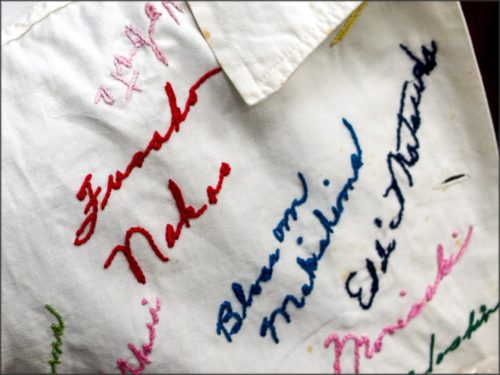

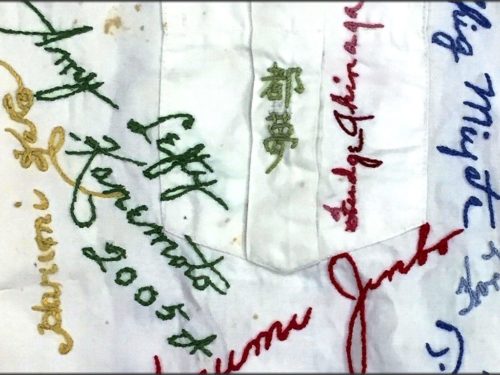

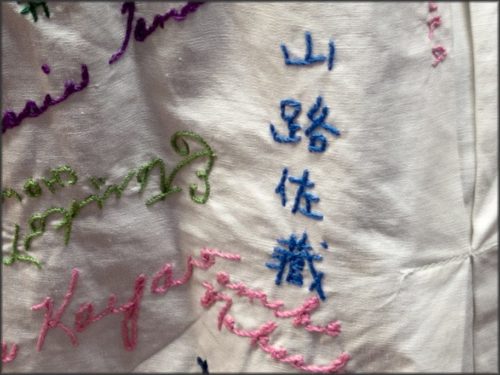

Fusaye Yokoyama’s signature shirt is covered with candy-colored names embroidered in cotton floss. It’s wrapped in stiff tissue paper at the Japanese American Archival Collection at California State University, Sacramento.

The accession entry provides only scant information.

Embroidered shirt, 1943. Owner: Fusaye Yokoyama, 2001/41

“Friends and acquaintances of Fusaye Yokoyama signed the shirt while she was at the Tule Lake Internment Center and then she embroidered over their signatures.”

But remove the garment from the archival tissue and memories of Fusaye’s life in Block 2019-F at Tule Lake spring to life: the names of 113 friends and neighbors who signed it in 1943.

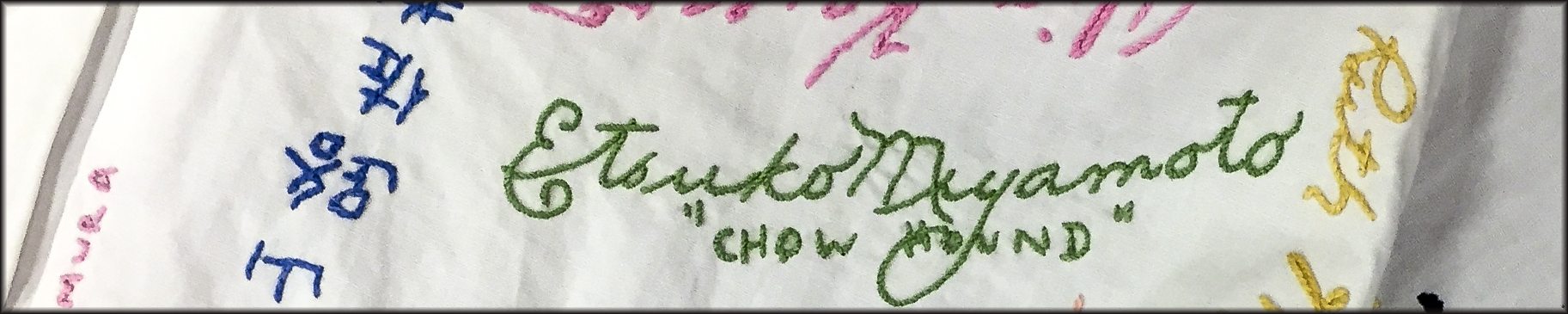

Every inch of the woman’s shirt is covered with names. “Etsuko Miyamoto chow hound,” “Blossom Makishima,” “Harry M. Nakahara ‘Dictator’ Block 20” and “S.P. Yogore.” Yogore is Japanese for “dirty, soiled, filth,” slang for the rebellious zoot suiters of the era, today’s gangstas.3 More sober is the embroidered name of Sakutaro Morimoto, who in 1944 was attacked while employed as a police officer in the Internal Security division at Tule Lake.4

Part autograph shirt, wartime artifact and prison memorabilia, the object is a cultural hybrid with immigrant names in Japanese and popular youth culture of the early 1940s. It was created through the gendered practice of women stitching together friendships using thread and needle. One wonders: did Fusaye ever wear it?

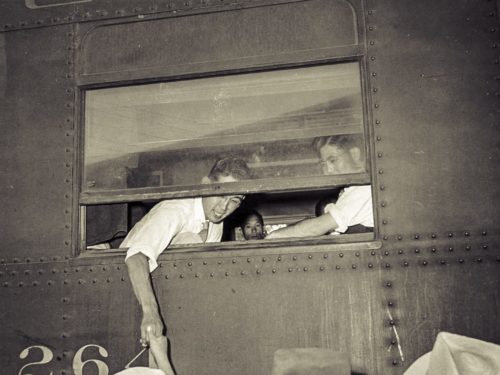

Fusaye was born in Perkins, CA, on Nov. 28, 1918, and graduated from Sacramento High School. At age 23, she was exiled to the preliminary Aborga detention camp in Marysville, on May 26, 1942, with her parents, who were immigrants from Hiroshima. Aborga closed on June 29 when some 2,400 people were transferred north by train to the Tule Lake camp near the Oregon border.

Another move was scheduled for the family a year later, out of Tule Lake. Those who had answered yes to two loyalty questions on a government questionnaire were allowed to leave the Tule Lake detention site for other camps. Tule Lake was being converted into a maximum security prison to make room for the thousands of “disloyals” from the nine other camps whom the government deemed too dangerous to remain mixed in with the “loyals.”

But many of the so-called loyal families who received permission to depart Tule Lake decided to stay put in order to avoid the upheaval of moving. Was the shirt created at a time when the Yokoyamas thought they might be leaving Tule Lake? In the end, they did not depart the camp until 1945. It closed in 1946.

| Fusaye's Shirt | |

|---|---|

| dimensions | H 21 in. (top of collar to shirt hem), W 15 in. (sleeve to sleeve) |

| material | cotton, plastic buttons |

| date | 1943 |

| creator | embroidery by Fusaye Yokoyama |

| site | Tule Lake, California |

| current location | Japanese American Archival Collection, California State University, Sacramento |

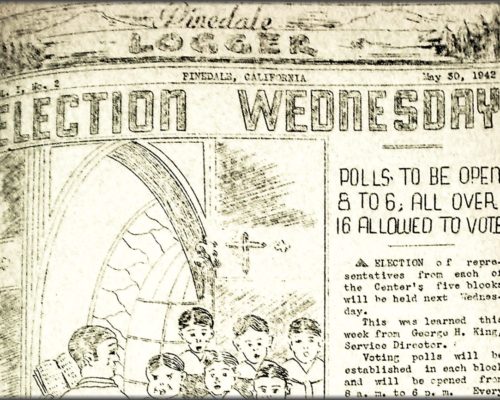

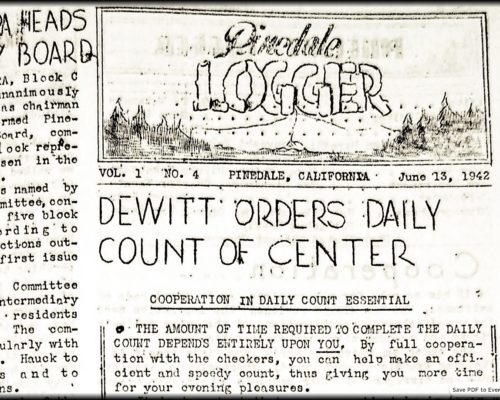

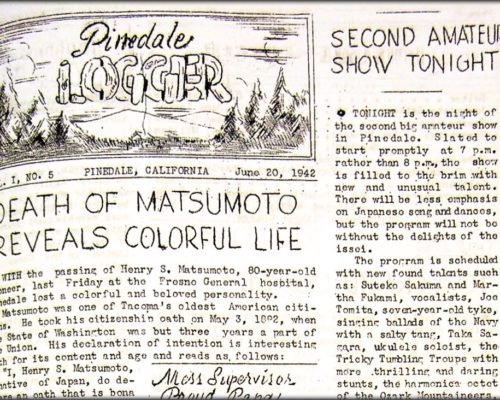

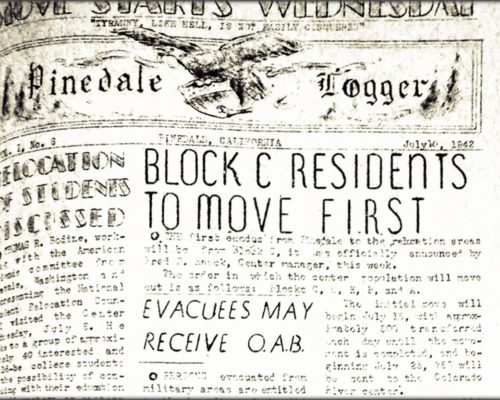

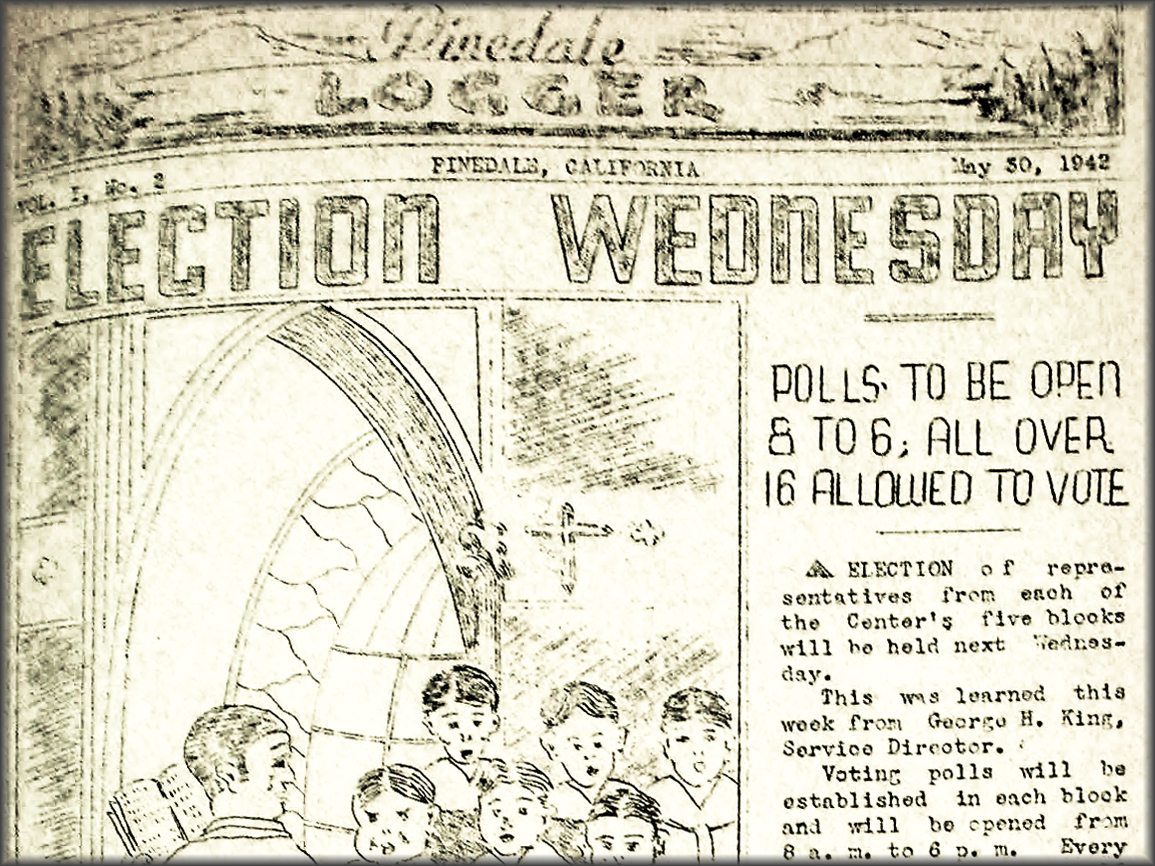

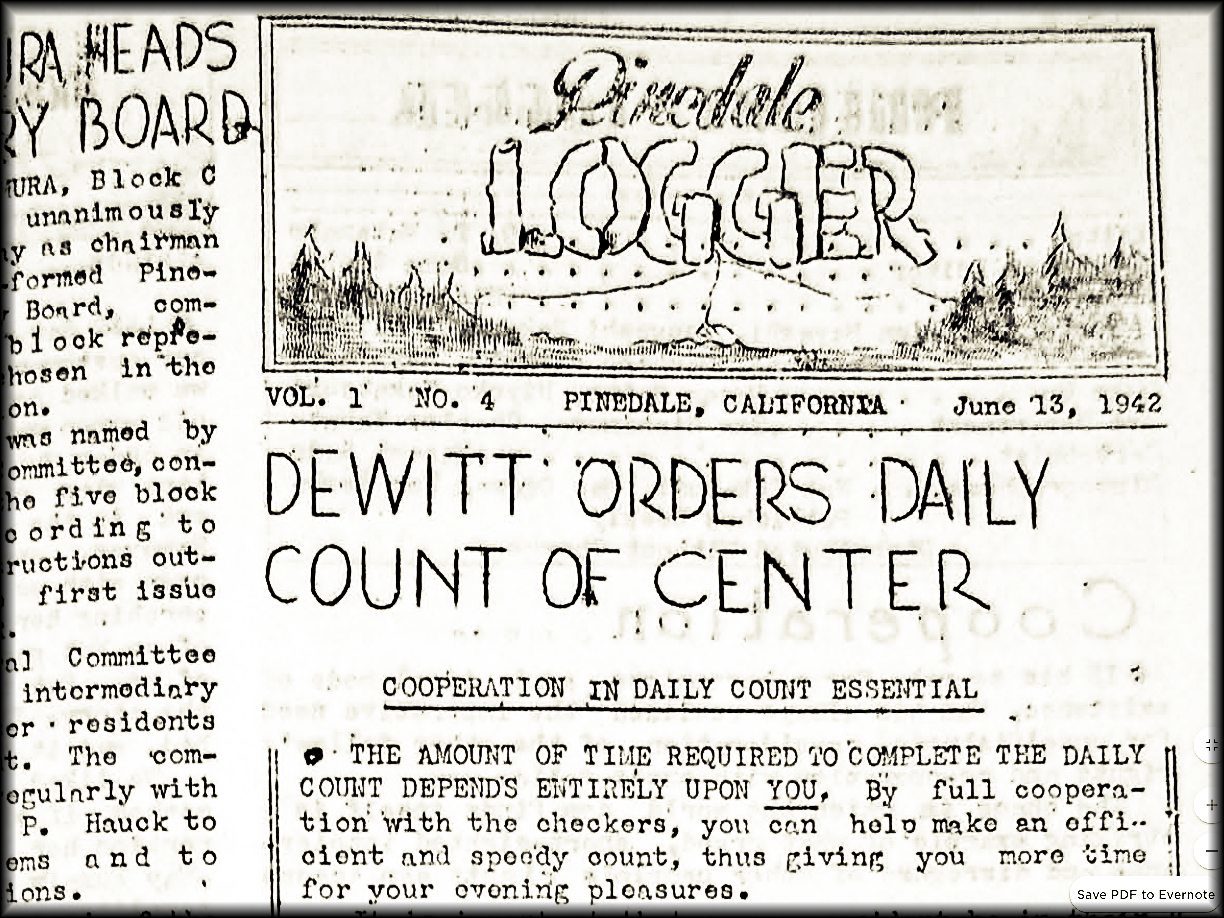

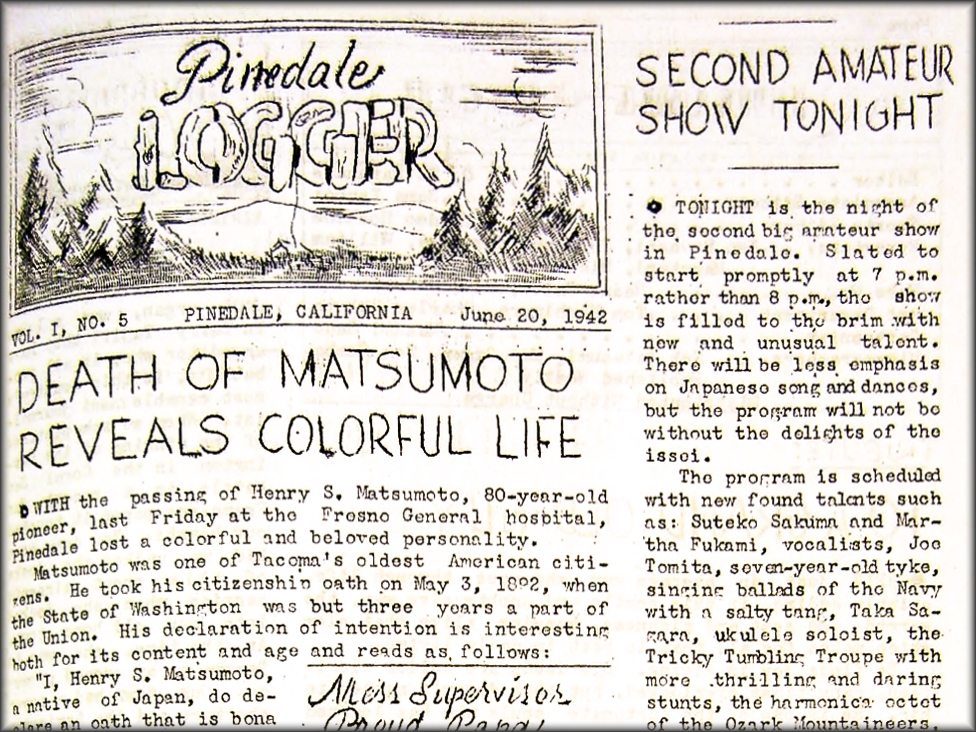

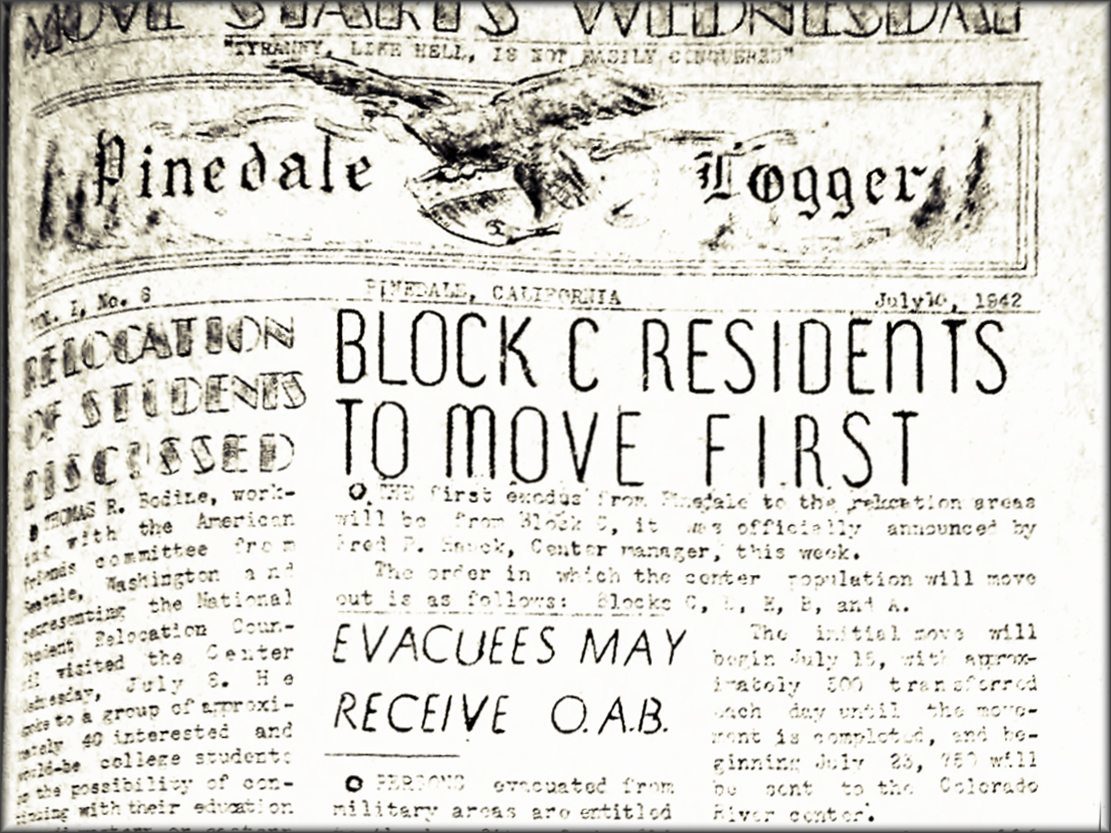

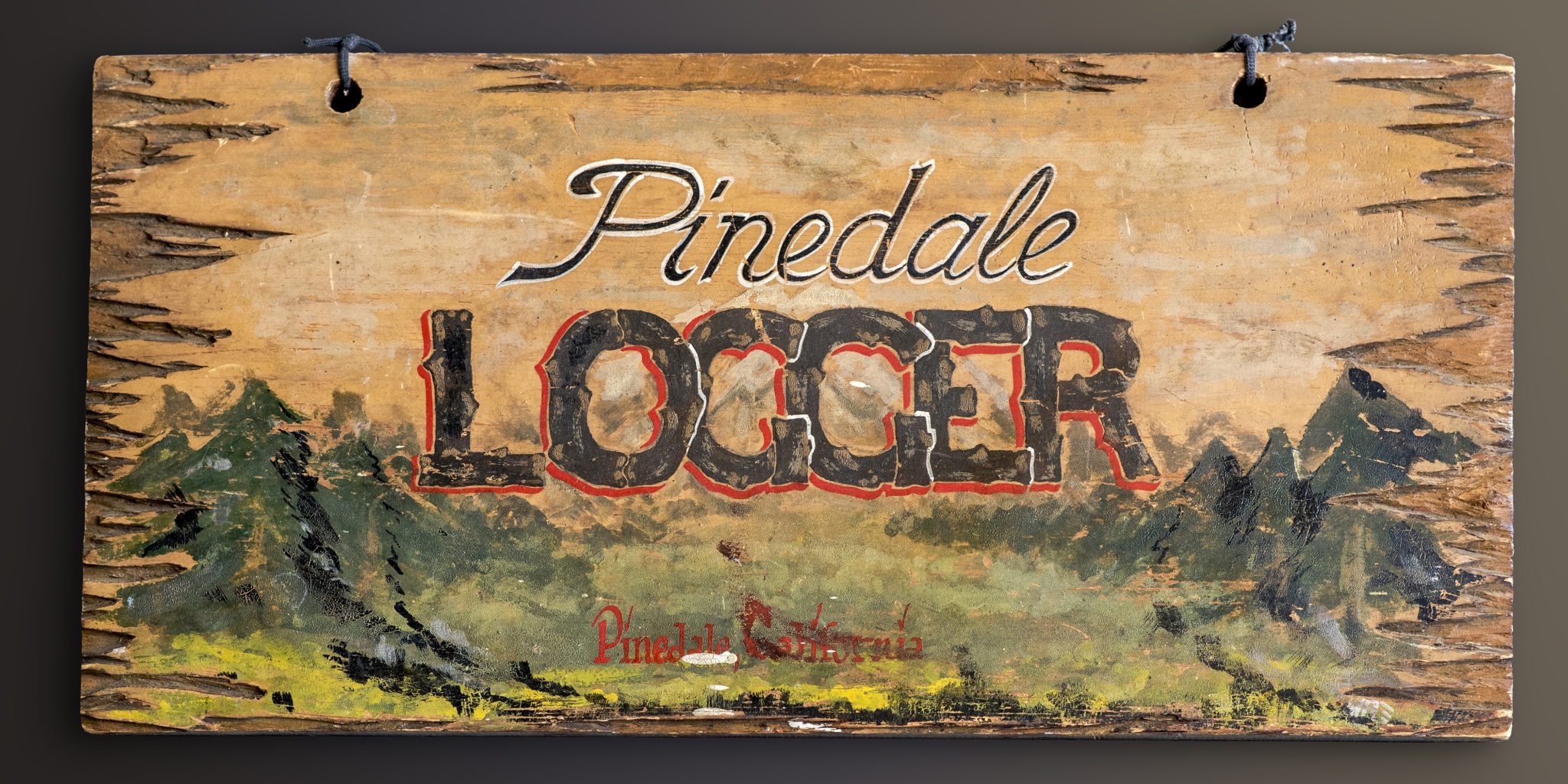

The Pinedale Logger Signboard

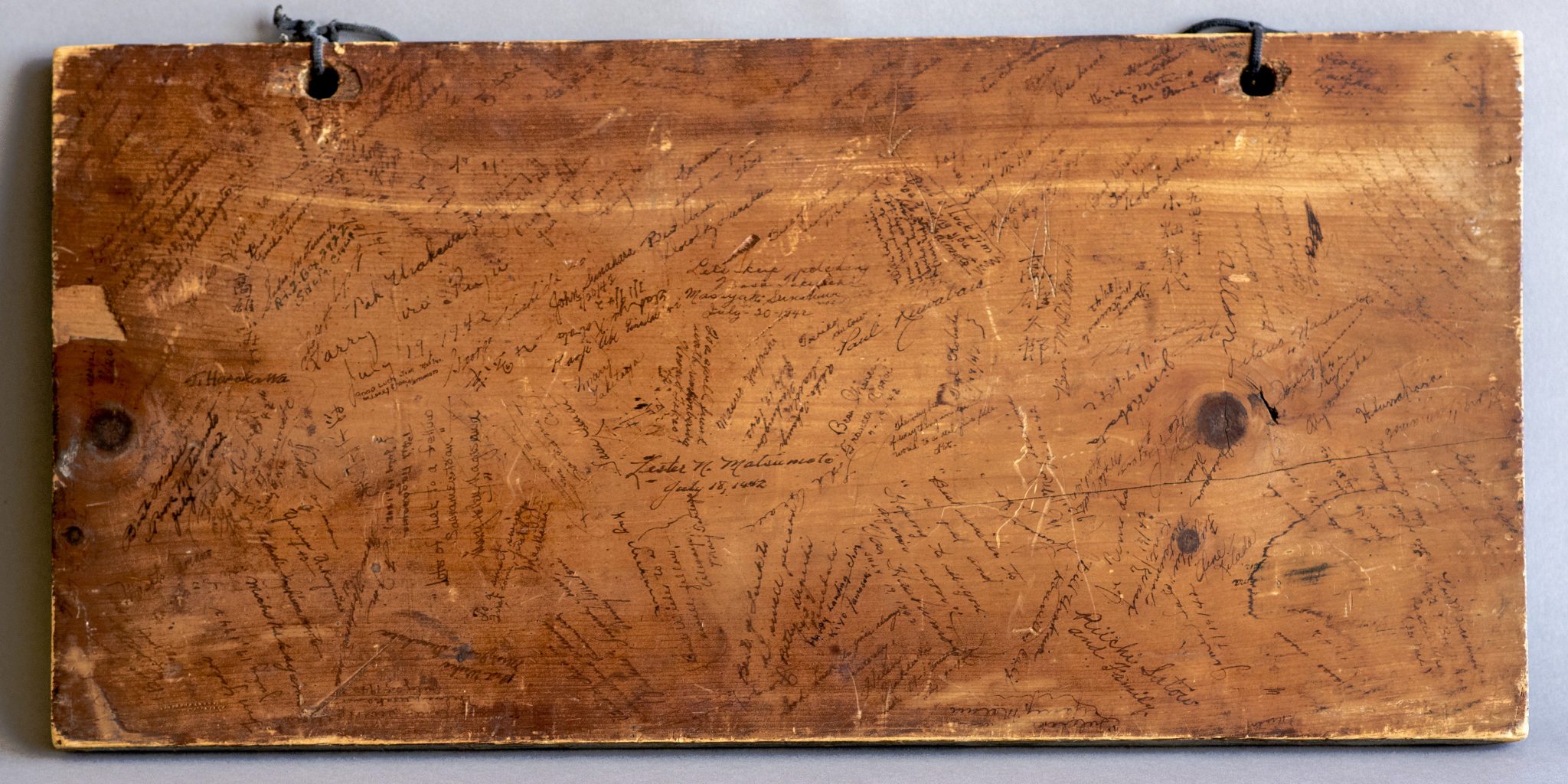

A rustic wooden plaque that would not look out of place in a mountain lodge or a vintage store hung for decades in the garage of the Nakatomi family in the Sacramento area. After Jim Nakatomi passed away, his son was cleaning out the space and took the Pinedale Logger signboard into the house to show his sisters.

For the first time, they noticed the mass of signatures on the back. It had been hanging next to deer antlers in the garage since 1956, but no one had turned the plaque over and viewed the reverse side.

Jim’s daughter took the signboard to the Tule Lake Pilgrimage in 2016 and learned that Pinedale was one of the government’s preliminary concentration camps north of Fresno. Pinedale operated for 78 days, from May 7 to July 23, 1942, housing a geographically-mixed population of 4,823 bewildered and frightened people from the Sacramento area but also from Washington and Oregon, due to lack of room in the Pacific Northwest detention sites. Everyone was later transferred to permanent camps in Tule Lake and to the Poston and Gila River prison facilities in Arizona.

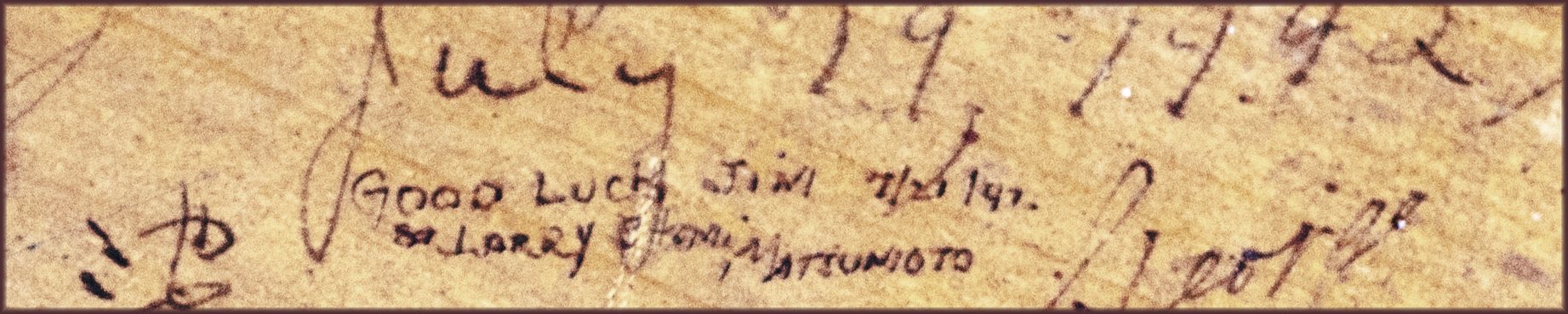

The “Pinedale Logger” on the signboard was also the name of the camp newspaper but it doesn’t appear that Jim was a staff member. Rather, his daughter, Barbara, thinks that her dad somehow acquired the signboard in the last days before Pinedale closed and got his friends to sign the back. Jim was unable to complete high school because the family needed him to help with the family farm. This leads Barbara to treasure the plaque as “the high school yearbook he never had.”

Many messages indeed read like yearbook wishes. “Happy landing, Jim – Kiyo Yamasaki” and “Lots of luck to a fellow Sacramentan – Mary Helen Nagashima.” But a few contain specific references to the signers’ plight as prisoners: “Best of luck in Tule Lake and wherever you go. Remember Pinedale? – Nancy Matsui.” Bill Urakawa of Roseville, California, shares space with Fumi “Archie” Matsumoto of Kent, Washington. A few comments suggest that the sign might have been a coveted memento: “To a smart swiper, first come, first get – Mas Narita” and “Lots of luck Jim. Your (sic) sure lucky with this souvenir – Martha K. Ikeda, July 18, 1942, Kent, Washington.”

After Pinedale, the Nakatomi family was transferred to Tule Lake. When the loyalty questionnaire was administered to inmates eight months later, Jim’s father, an immigrant, was angered by his treatment by the U.S. government. He’d had enough and wanted to repatriate to Japan. This caused a quandary for Jim, who loved his father but did not want to live in an ancestral homeland he had never visited. Jim’s father passed away at Tule Lake and the children remained at the camp until the war ended.

His father had one request before he died. He asked Jim to retrieve the new floor cabinet radio that the police had confiscated in a sweep of their home before the family was removed. But after the war, when Jim went to the police station with a receipt, the official laughed and said, “none of your property is still around.”

Barbara later entered a career in law enforcement in Sacramento. She said, “Maybe after serving 31 years in the Sherriff’s Department, I was able to atone for the way that my father was treated. I was proud to serve with concern and compassion.”

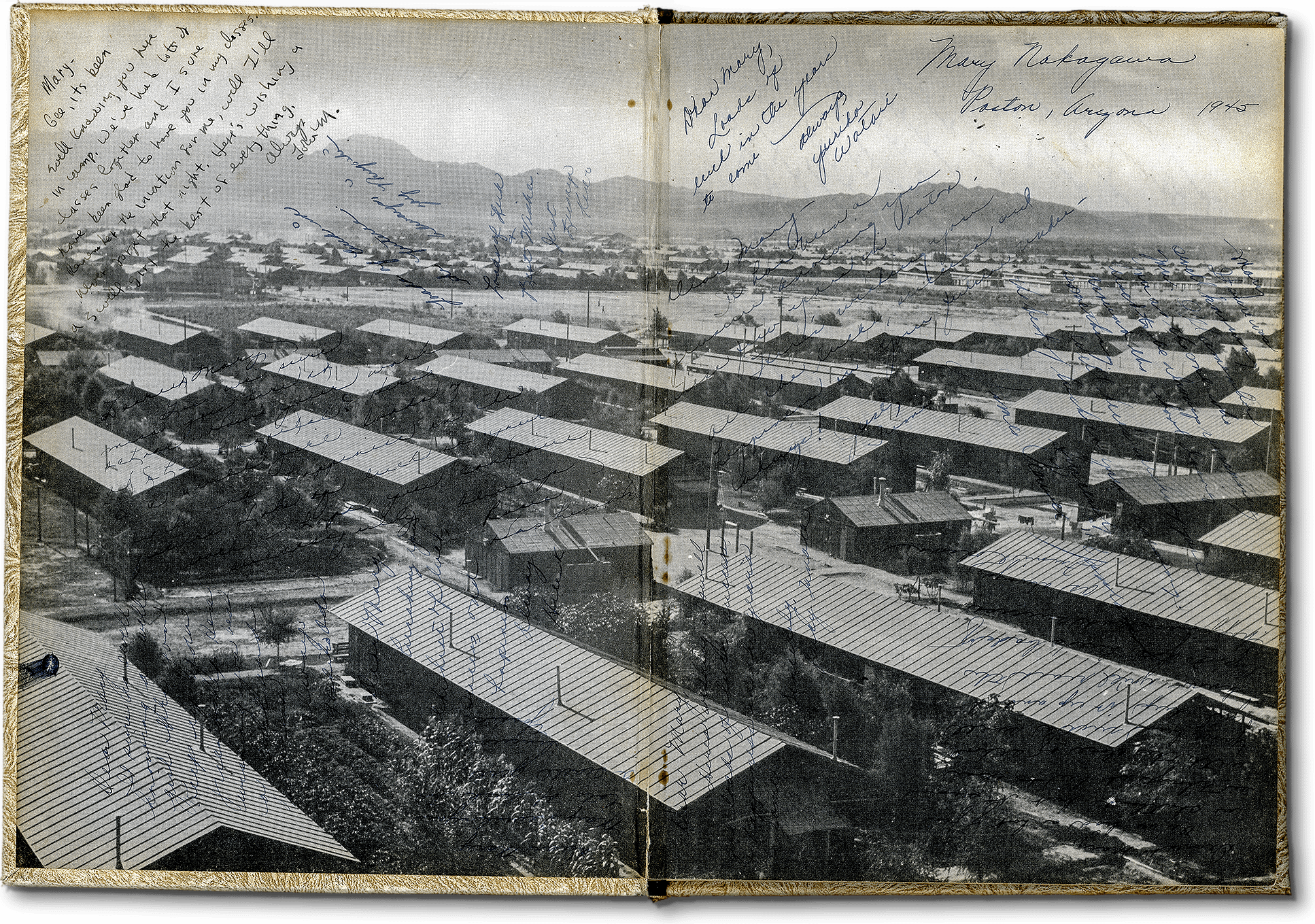

Mary's High School Yearbook

As typical and bland as they come, the following inscription in a high school yearbook is part of a ritualized marriage of text, image and signature. It’s a common rite of passage for high school students, a border crossing in time and place from protected childhood into the rights and privileges of adulthood.

Because cameras were banned during much of the incarceration, yearbooks made their appearance late in the Poston timeline.

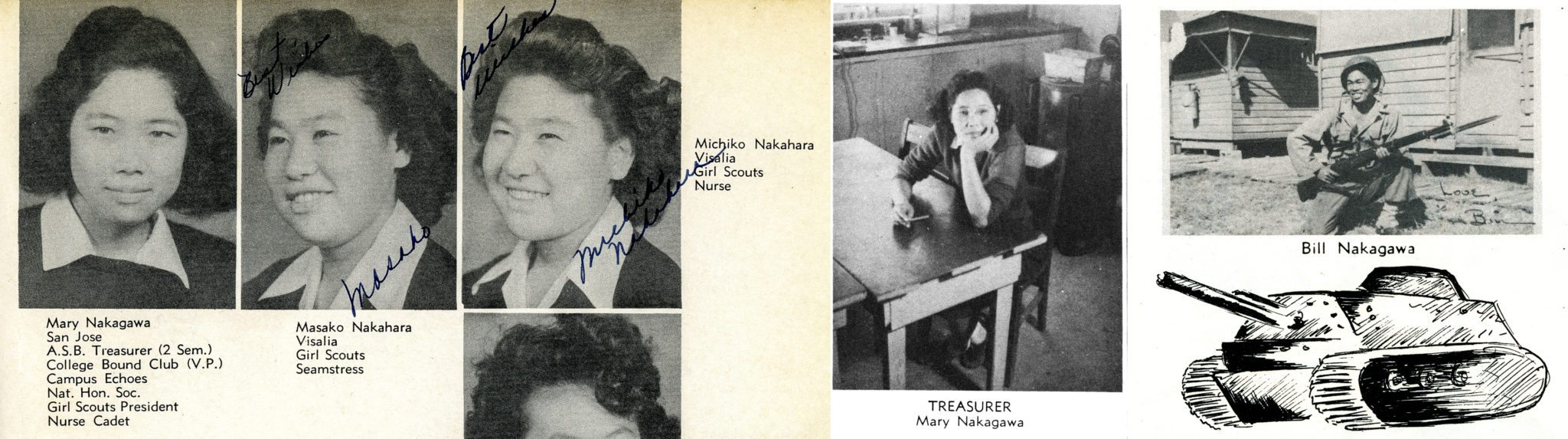

The note is from page 64 of senior Mary Nakagawa’s Parker Valley High yearbook. Almost everything appears to be normal “here.” The drawings of smiling students posing, the group photos of the student council, basketball teams, baseball teams, the cooking class, the badminton champs, the full page devoted to the “personality” queen and king, Helen Ozaki and Hank Yamada. This publication is a collection of subjects without verbs.

Verbs could complicate everything. Like “incarcerate.” Like “resettle.”

All of the students captured between the padded embossed covers are American Japanese. “Here” is the Poston prison camp high school sequestered deep in the Arizona desert. The year is 1945. Mary, her parents, and her siblings have been confined here in Camp 3 for the past four years against their will. The war is over. They will soon be given their $25 departure allowance and a train ticket to anywhere in the United States they wish to go.

They are uneasy about going “home,” although they will return to the San Jose area where they had been truck farmers before the war. They are afraid to go anywhere else. Better to stay within the bounds of the yearbook where Mary is repeatedly referred to as a “swell gal” by her peers, where she has a position secured by alphabetical order, where her bonafides include A.S.B. Treasurer and Girl Scouts president.

Left: Mary Nakagawa; center: Mary Nakagawa, treasurer,

Right, Mary’s brother Bill Nakagawa from the yearbook page dedicated to Parker Valley High alums fighting in Europe for the U.S. Armed Services.

The end pages are where the bid for normalcy fails. This is where their signatures gather, lines of ink run helter skelter over a grim black-and-white image of endless rows of Poston barracks. The sentences are lost, broken up by the harsh light and dark sawtooth staccato of rooftops and walls. It is only in the open sky where the words are clear.

by David Izu, son of Mary Nakagawa

Gee just think this will be the last year here in camp. Gee it's been swell knowing a friend as you. Keep up your kind way.''

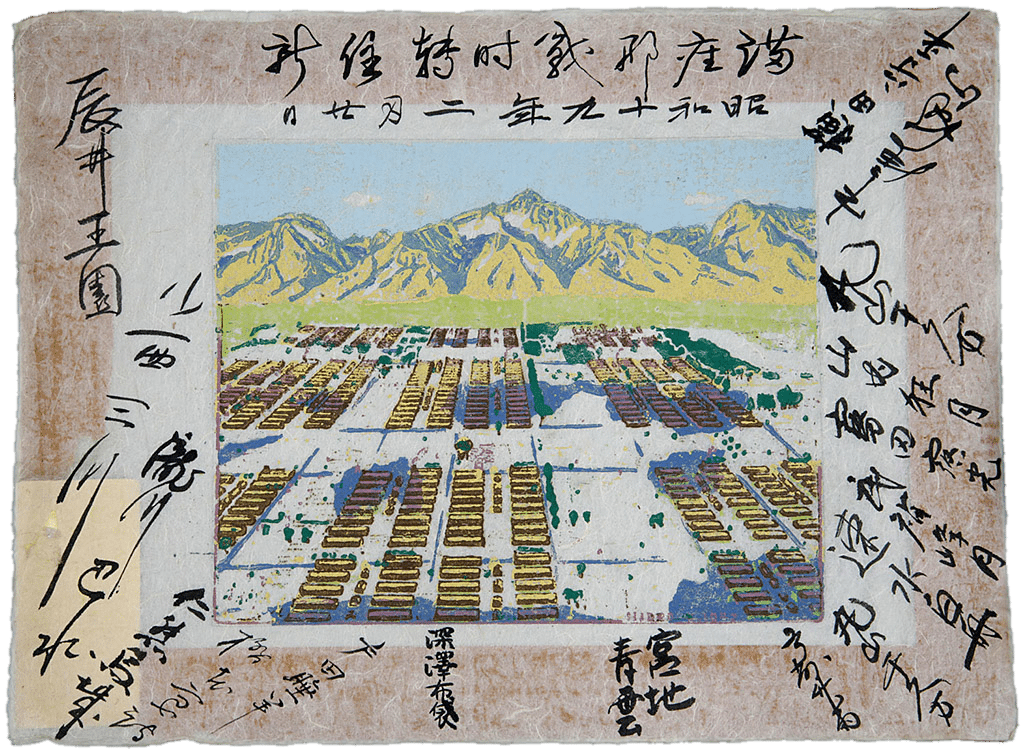

The Kobashigawa Print

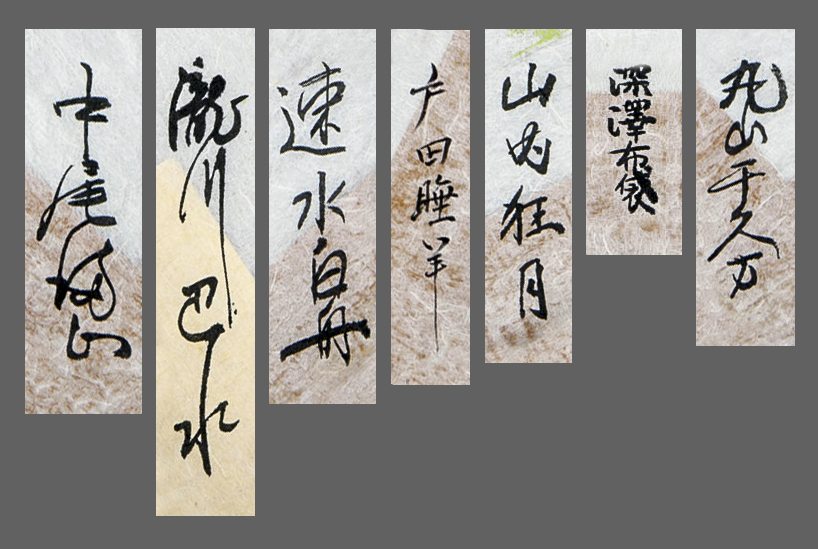

The writing of one’s name in Japan was traditionally done using a brush, with the characters written vertically from top to bottom. In some cases, the script could be written horizontally, from right to left.

In the case of a formal signature on an art piece, the act of writing will be preceded by a period of slow, continuous rubbing of an ink stick in a small pool of water in a suzuri inkstone well to produce the correct color and consistency of ink. In a grouping of signatures, where to place one’s name in relation to others’ would be weighed, along with the awareness that one’s brush strokes will be judged as a visual expression of character and learning.

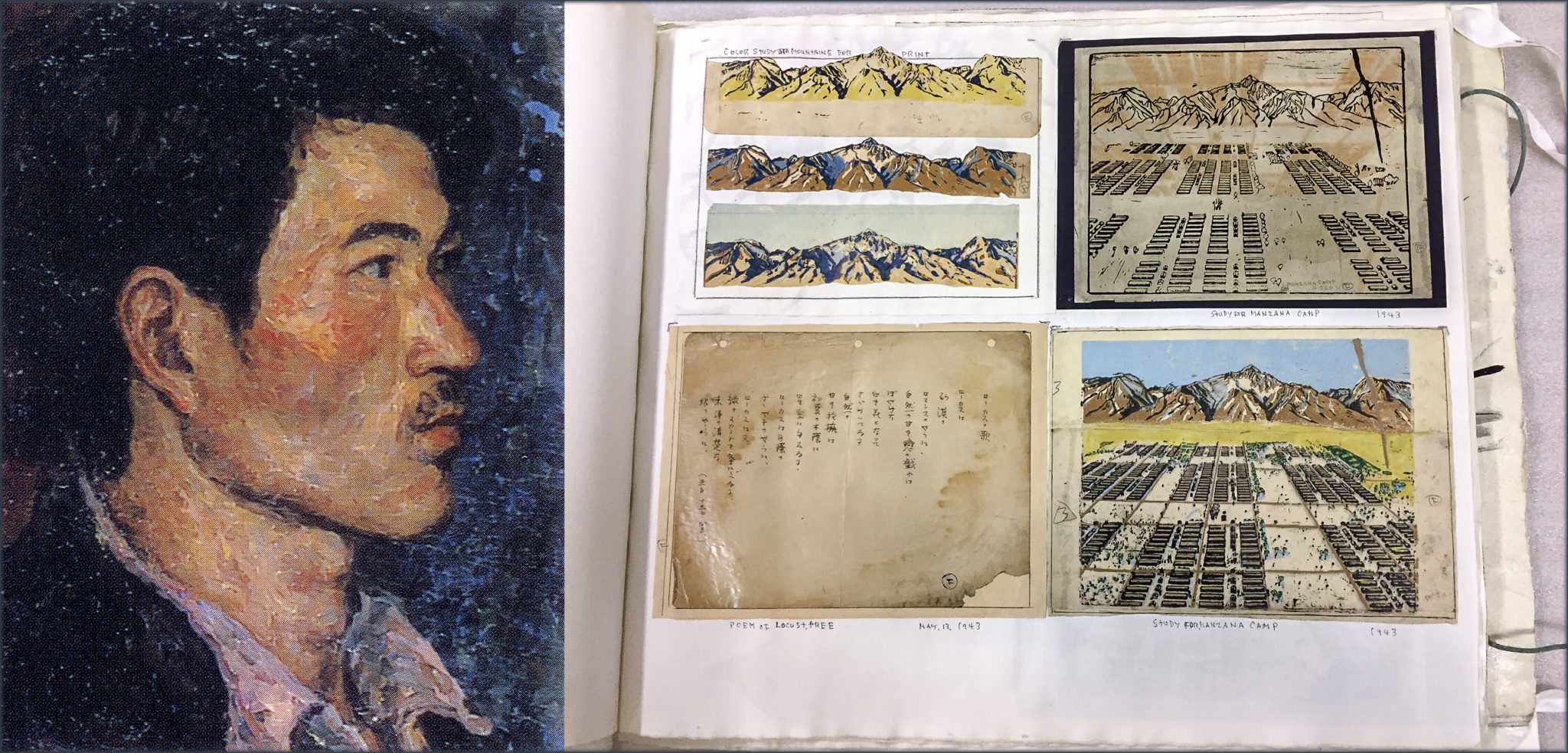

Even under the shadow of guard towers at Manzanar, such aesthetic considerations would have been in the minds of the 17 poets who signed a lino-block print made by Hideo Kobashigawa. It’s not known what the occasion was for signing the print. The date that is written across the top of the piece, Feb. 20, 1944, happens to be one day after the second anniversary of President Roosevelt’s signing of EO 9066, which paved the way for the removal of Phoenix-born Hideo and his brother from Los Angeles to Manzanar. Hideo was 27 years old when the print was signed by the poetry club members.

Courtesy of the National Park Service/Manzanar National Historic Site

Like the Japanese ukiyoe woodblocks that this landscape evokes, the lino-block print was made in multiples. One version has been reproduced and is sold by the nonprofit Manzanar History Association to support the Manzanar National Historic site, which received a record 105,307 visitors in 2016. But that version does not have the names of the poets.

The presence of the poets’ signatures in the version shown here is an inextricable part of its aesthetic power. The signatures of Tatsui, Konishi and Jinretsu hover above the Owens Valley and outside the perimeter of the camp, a floating world high in the eastern California sky.

Less is known about the activities of the Manzanar Wartime Poetry Club whose name is written across the top of the print. Full translations of the writers’ names and their poems await future research.

By the time the poets signed the print, Kobashigawa, who also wrote poetry, was no longer at Manzanar. He had been transferred from the camp in the spring of 1943 to Tule Lake because of his answers on the loyalty questionnaire. There his work grew more somber.

Right: The Kobashigawa album, photo: Nancy Ukai. Courtesy of the Japanese American National Museum.

The Kobashigawa album, in the collection of the Japanese American National Museum, will be introduced more fully later in this project.

Credits

Feb. 13, 2018

by Nancy Ukai and David Izu

art direction: David Izu

cover images: David Izu 2017, Charles Mace 1943, and Joe McClelland 1943

special thanks to:

Julie Thomas, Special Collections and University Archives, California State University, Sacramento, Barbara Nakatomi, Izu family collection, Junko Okada, Noriko Sanefuji, Ben Kobashigawa, Bernadette Johnson, Alisa Lynch, NPS/Manzanar National Historic Site, Japanese American National Museum.

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service,

Japanese American Confinement Sites program