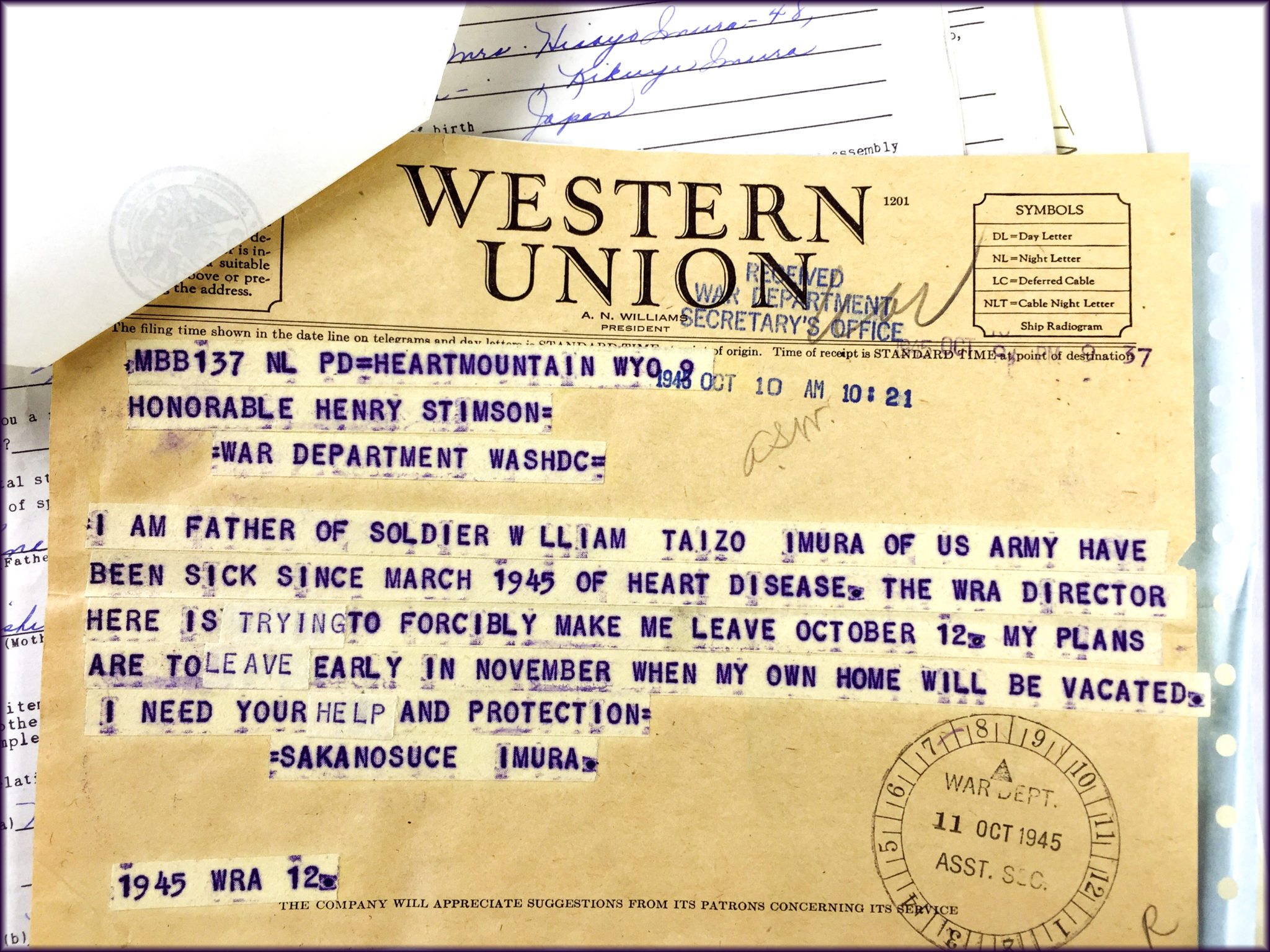

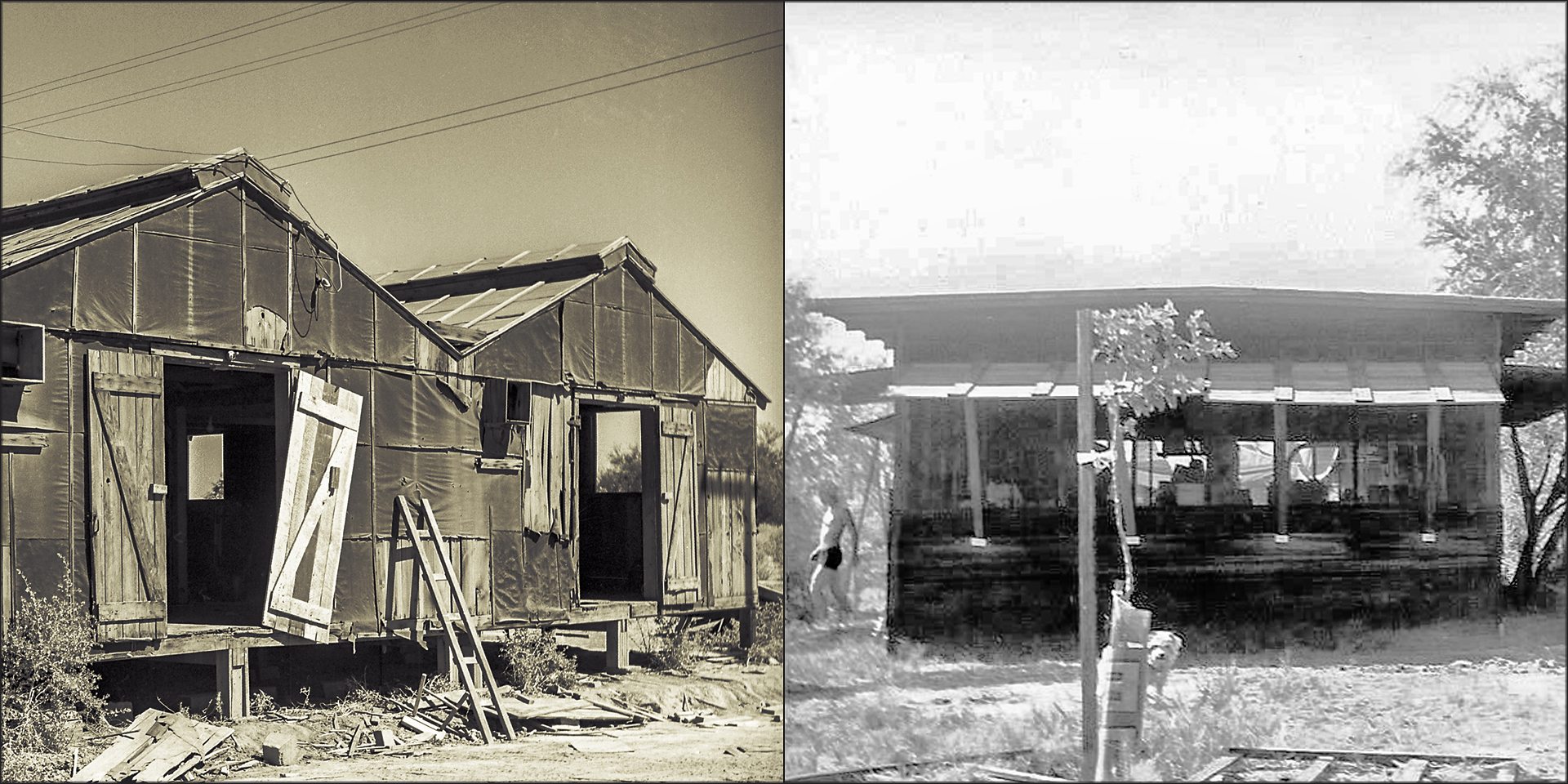

After the war ended, Walter Gudarian was hired to take down the barracks at Poston 3 in Arizona. He found himself in a bone-dry landscape of ramshackle buildings littered with broken dishes, scrap wood and a stray dog.

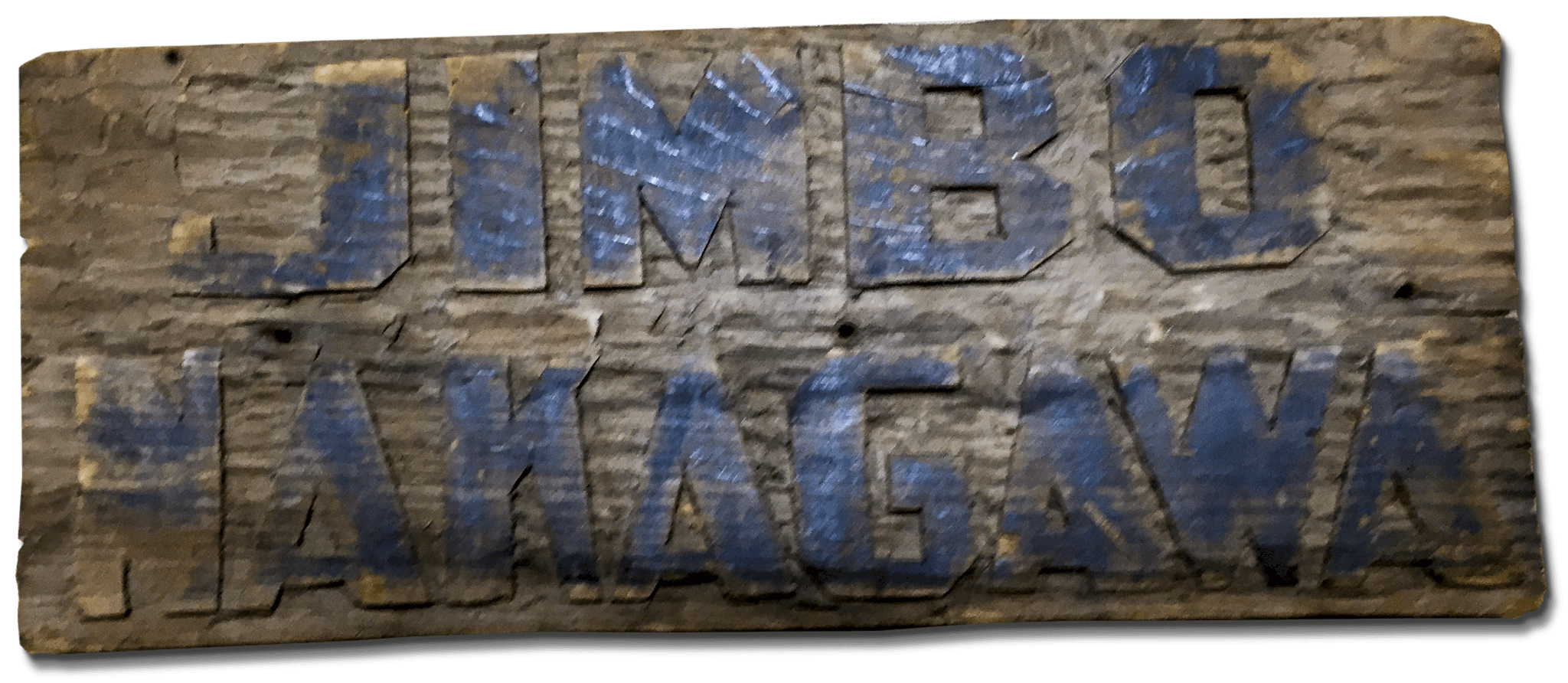

He also found evidence of specific people who had been incarcerated there by their own government: handmade nameplates crafted from wood. The nameplates had been left behind on the barracks. They bore surnames like Kuyama and Nakaji. One said Dr. Takeda. Another had the name Jimbo Nakagawa.

Walter took the stray dog, the name plaques and a pile of barrack wood to Blythe Island in the Colorado River. Sometime after 1945, he built a cabin there using the Poston lumber. Maybe he hung the nameplates on its walls.

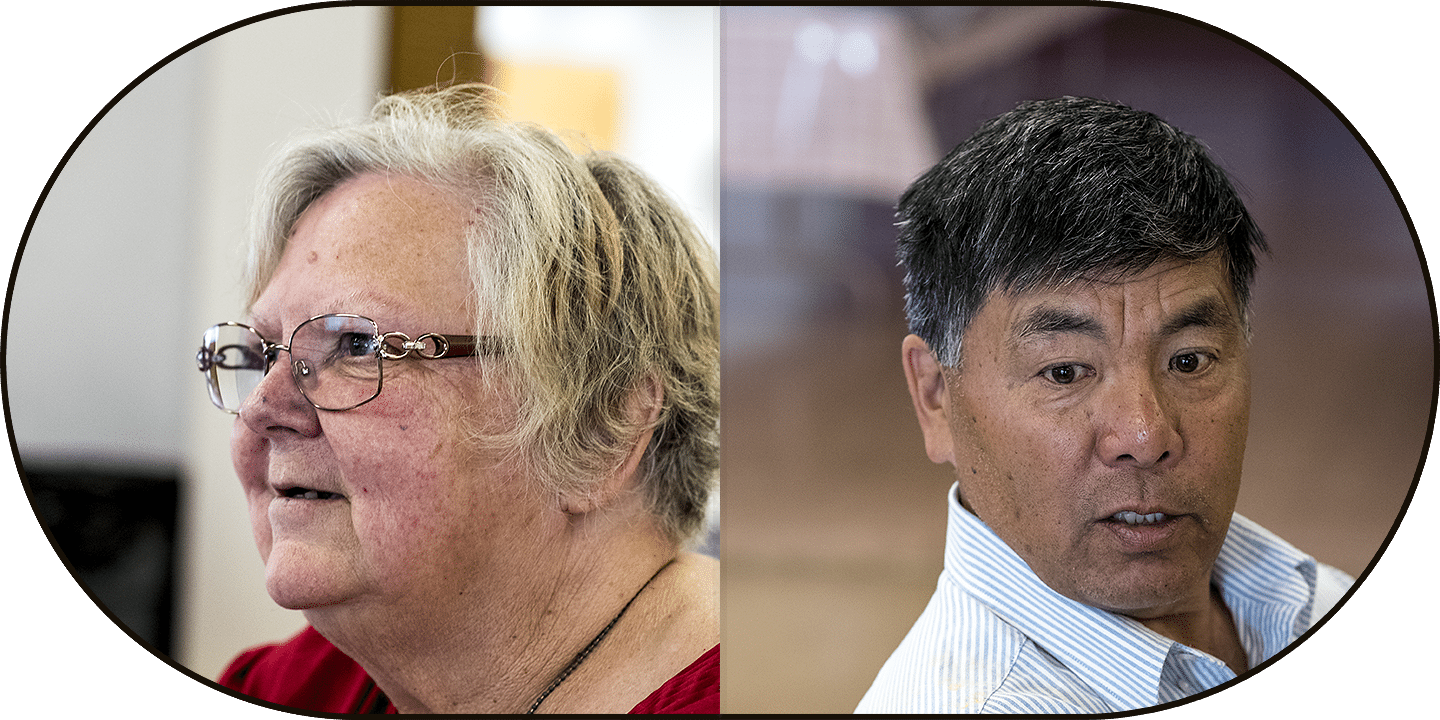

Some 70 years later, the plaques made their way to his step-daughter, Mary Allred, in Stockton, California. Mary said that she knew “these plaques have a story to tell.”

She stored them in a closet while pondering what to do with them. In 2015, she walked over to her church, Calvary Presbyterian, which is a longstanding Japanese American community place of worship, and handed them to Dean Komure, a rancher, church member and friend. He also was president of the local French Camp chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League.

“He would know how to take care of these. I’ll just ask him,” Mary recalled thinking.

“I said to him, ‘Dean, I have something I want to donate but it shouldn’t go to the rummage sale.’ And he was just blown away. ‘Where did you find these?’ he said. And so I told him.”

Dean decided to ship them to a JACL friend in San Diego who was a history buff.

Henry Isakari, the friend, was delighted — and stumped. He was aware that San Diego was one of many Japanese American communities that had been exiled to Poston, but how to make a connection between the nameplates and families — if one even existed?

“Many of the nameplates contained common Japanese names, such as Takeda and Nakagawa, so it would be a daunting task to find the exact families who had made them,” he said.

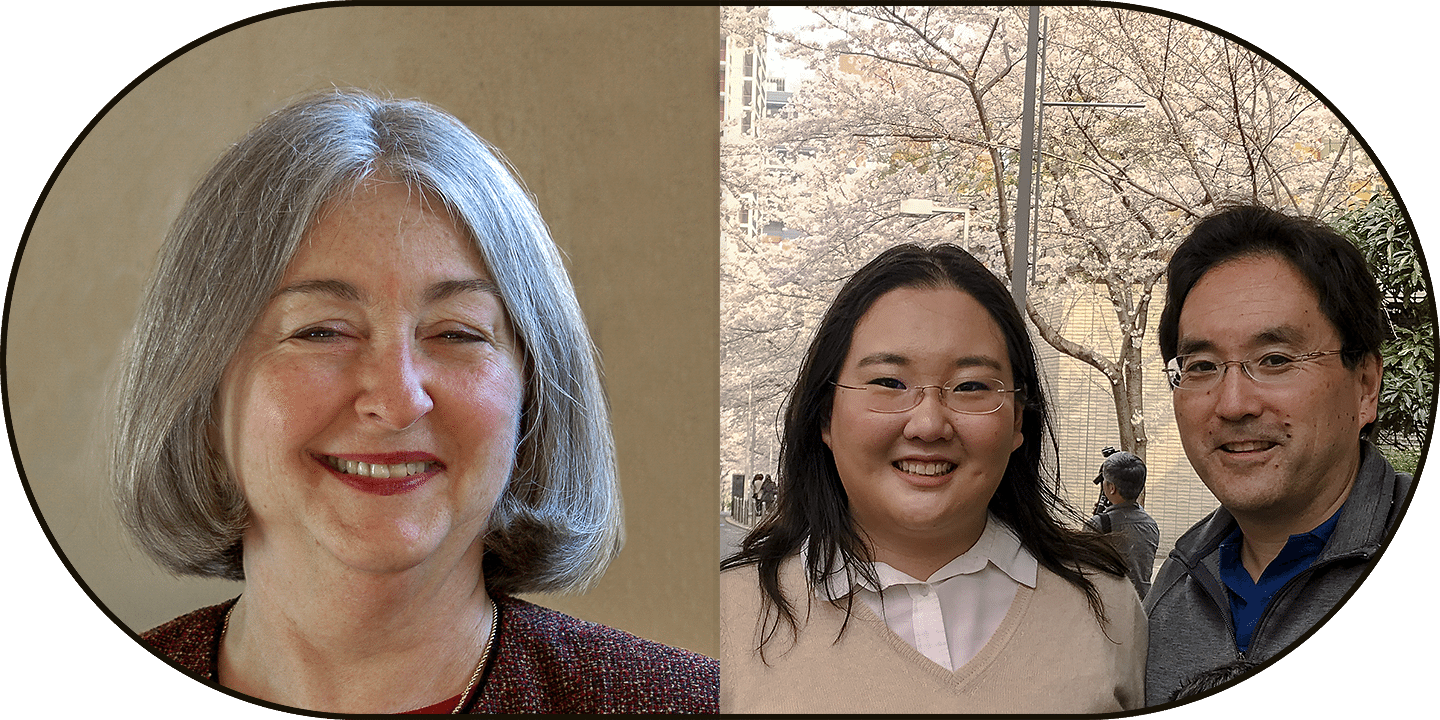

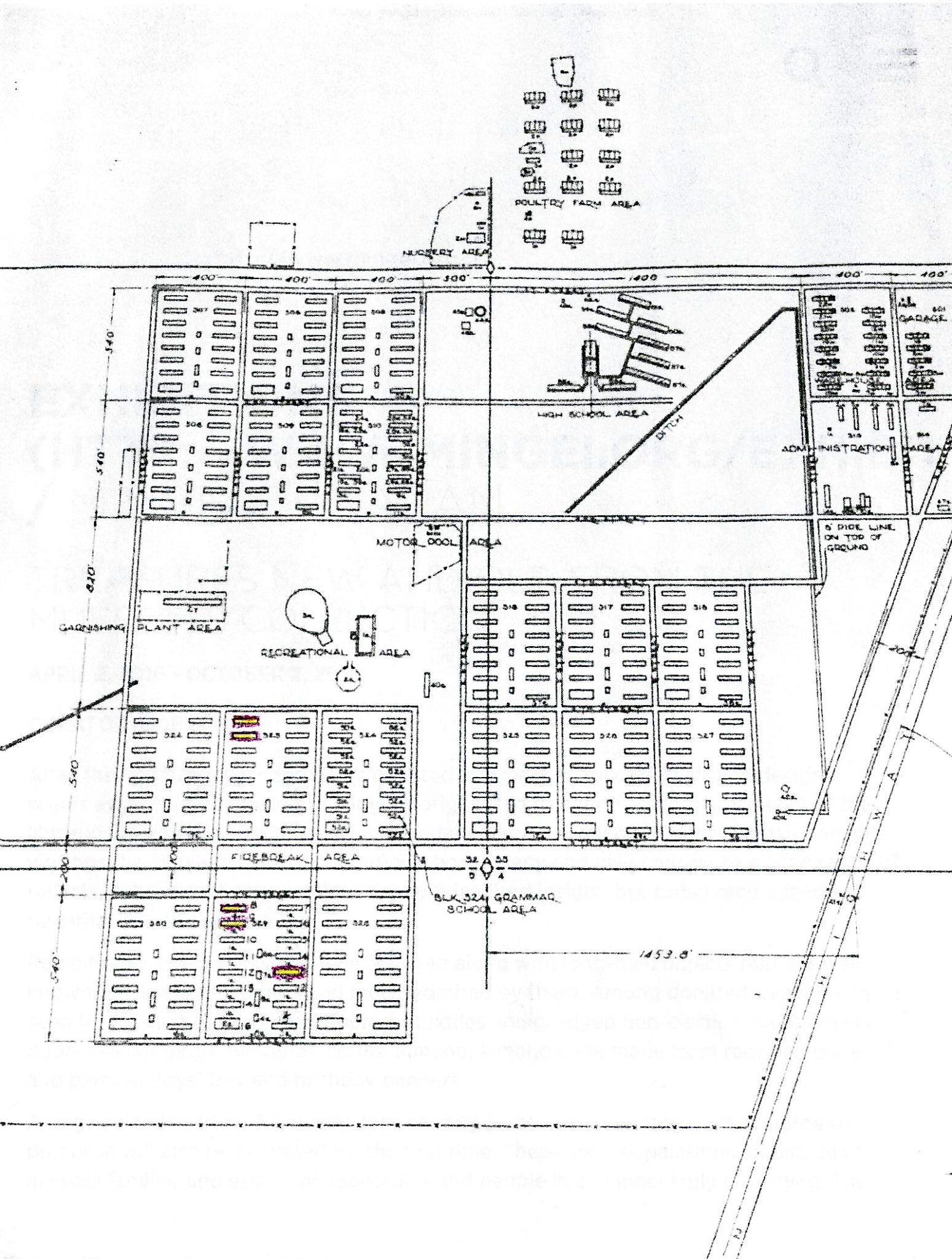

Henry put together a small research team: himself, his daughter Emily, who is an Asian American Studies major at UCLA, and Linda Canada, archivist at the Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego. They researched the family names online but the breakthrough came when Linda went into the archives and brought out maps of Poston.

Linda and Emily noticed that clusters of names plotted on the barrack maps corresponded to those on the nameplates. They had found the area where Walter Gudarian took down the barracks and saved the name signs. Then they were able to cross-reference the names in other sources to gather biographical information.

Not a number

As in a normal prison, all detained civilians in the WRA camps entered into a dehumanizing life of numbers: ID numbers, block and barrack numbers, and endless rows of uniform buildings guarded by watchtowers and armed sentries.

Finding one’s barrack among the maze of buildings was akin to locating one’s car among thousands of autos, all of the same make, model and color, in a parking lot that measured hundreds of acres, wrote one scholar.1

Artist Miné Okubo wrote, “All residential blocks looked alike; people were lost all the time.”2

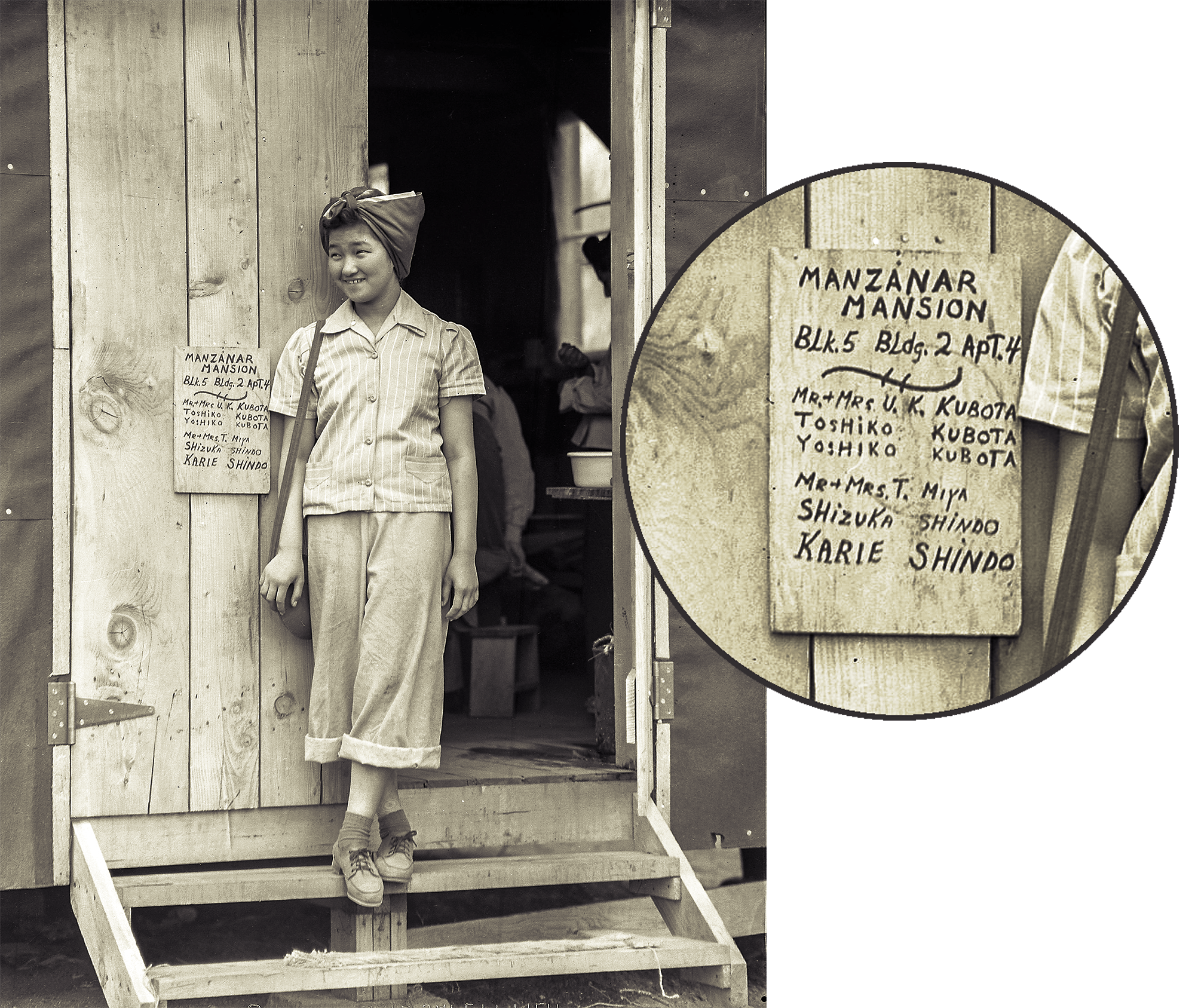

Soon after the first detention sites opened in spring of 1942 — the so-called assembly centers that were hastily thrown up in fairgrounds and racetracks — nameplates began to appear.

Like wildflowers in the desert, name plaques sprouted and spread with abandon. Inked lettering was common on early plaques but creativity blossomed; metal packing tape was hand-curled to create cursive letters and knots in scrap wood were artfully employed. Young people created signs for their “Manzanar mansions” and at the Pinedale prison site, redwood and pine plaques invited friends to “Tumble Inn” and “Breeze Inn” (unless the occupants were “Knot Inn.”)

After arriving at the Santa Anita racetrack, “we had to carefully consider how to make our spaces into a ‘home,’” wrote immigrant Masao Yamashiro, in an essay written in Japanese at Tule Lake.3 “Nameplates first appeared as aids for visitors and mail delivery,” he wrote.

“As I walk around camp I see many different styles of nameplates. I’m not particularly interested in Japanese surnames but I’m fascinated to see names written in sumi ink, carved in relief, nameplates using various colors, horizonal designs, nameplates with striking lines, and even humorous ones.

“There’s even a nameplate so beautifully written in cursive that you might not feel comfortable leaving it outside. One nameplate features the backdrop of a mountain and river, carved in relief. Another nameplate looks like an antique that has seen better days, waiting for the end-of-the-year sale. Yet another one has a cartoon advertising the bachelor owner’s desire to get married.”

Perhaps the nameplates were a way to reclaim one’s name when everything else had been taken away. They seem to say, “I am not a number.”

The Poston collection was donated in 2018 to the Japanese American Museum of San Jose and now hangs on a gallery wall, a far cry from its carceral origins. Thanks to a network of grassroots preservationists, a safe home was found.

Behind the names: the San Diego team’s research

Dr. Takeda

Dr. Isamu Takeda (May 12, 1882 – Sept. 21, 1945). Dr. Takeda was the only Japanese dentist in the San Diego Japantown for much of the prewar period. He emigrated from Niigata Prefecture in 1907, arriving in Seattle prior to the enactment of the Gentleman’s Agreement which curtailed Japanese immigration. He graduated from the elite Waseda University in Tokyo and in 1917 from Western Reserve University in Ohio, with the degree of Doctor of Dental Surgery.

His 1918 World War I registration card shows that Takeda lived at his office at 506 5th Street, in the heart of Japantown. He returned to Japan in 1921 to bring back his wife Fukuko, a Tokyo native. Four daughters were born to the couple; the entire family was exiled to Poston. Dr. Takeda passed away in 1945, soon after his release, at age 63.

The Kuyama family

The Kuyama family of San Diego lived in the barrack across from Dr. Takeda and his family in Block 329. The 1940 census lists five Kuyama family members: immigrant Takashiro Kuyama (1888-1981), wife Sumako (1898-1974), and their children Paul (1916-1992), Ellen (1922-2014) and Howard (1928-2014).

Paul studied in Japan and returned to the U.S. in 1940. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in April, 1941.

Ellen was in her early 20s at the time of exclusion and was forced to leave her studies at San Diego State. Her daughter, Beverly DiDomenico, accepted an honorary degree on behalf of her mother, Ellen Kuyama Matsumoto, in 2010. Ellen had married into the Matsumoto family of Chicago, IL.

Youngest son Howard graduated from the Poston High School class of 1945. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1946 and later moved to Sacramento.

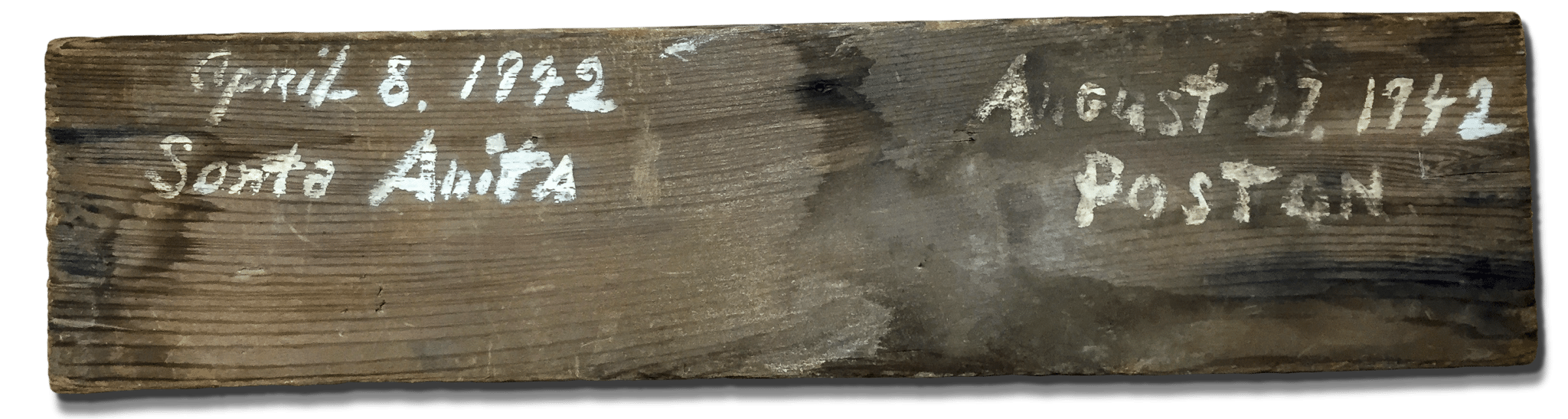

The back of the Kuyama nameplate memorializes the family’s removal to the Santa Anita racetrack on April 8, 1942, and intake into Poston four and a half months later, on August 27.

Jimbo Nakagawa

The “Jimbo Nakagawa” nameplate took more time to research because the group assumed that “Jimbo” was a nickname for James, setting them off on a search for Jim Nakagawa. “It was finally discovered that this is not a first name, but rather the combined names of two fishing families related by marriage,” according to Linda. An issei immigrant widow, Mrs. Jimbo, married Mr. Nakagawa.

Less information was able to be found on these three nameplates.

There is a large Takehara family from San Diego but the youngest son, Joe Takehara, a nisei in Chicago, was contacted and had no recollection of the plaque, a not unusual circumstance given the lapse of seven decades.

A large Nakaji family still lives in San Diego but none of the descendants that Linda Canada talked with remembered the rustic plaque.

Junkichi Kagawa (b. 1918) of Block 316 received short-term leave to Hunt, ID, in 1945, according to the April 21, Poston Chronicle, p. 3 (“To a brighter future”). He and wife Shizue (b. 1919) had a baby girl named Naomi, born in 1942.

In memoriam: Dianne Kiyomoto (1954-2018)

Dianne Kiyomoto, a descendant of Poston concentration camp 3, Block 305, grew up in Reedley, California. She passed away on May 19, in Fresno. Among other projects, she worked tirelessly for years to compile detailed “Block books” that mapped thousands of the 18,000 people who were incarcerated at Poston’s three camps. We were in touch with her via email for this essay because her work for the Poston Community Alliance helped Linda Canada, Emily Isakari and Henry Isakari connect the Kuyama and Takeda families to the nameplates salvaged at Poston. Dianne’s dedicated work will live on. We send our deepest condolences to the Kiyomoto family and to the Poston community.

Credits

by: Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: Nancy Ukai 2017, Fred Clark, Poston, 6/1/1942

Special thanks to:

Dean Komure, Mary Allred, the Gudarian family, Henry Isakari, Emily Isakari, Linda Canada, Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego, Jim Nagareda, Pam Yoshida, Japanese American Museum of San Jose, Dr. Junko Kobayashi, Reiko True, Sharon Imura, Reynold Kagiwada, Amy Tomine, Japanese American National Museum, Poston Community Alliance.

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service,

Japanese American Confinement Sites program