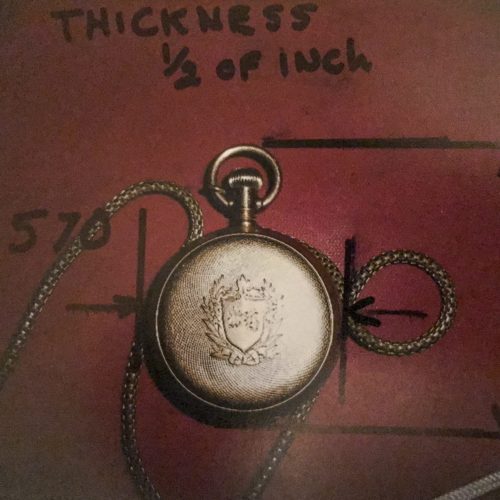

In the spring of 1942, Wasuke Hirota, an immigrant from Hiroshima, received a gold pocket watch from the company where he had worked for 38 years. After the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, many people of Japanese ancestry lost their jobs the next day. Wasuke was the rare exception, perhaps even the only case, of an immigrant who was given a handsome gold watch by his employer, a citrus firm in Azusa, California.

left: Wasuke’s pocket watch, engraved with his initials. photo: Saya Russell 2017

background: The Azusa Citrus Association packing-house, 1921, courtesy of Citrus College, Hayden Memorial Library

It was a “retirement” gift.

Wasuke, an irrigation expert, then proceeded to work for the Azusa Foot-Hill Citrus Company right “up to the time he was taken” with his family to the Pomona concentration camp.1

The gold timepiece, engraved with his initials, traveled with Wasuke for the next two and a half years through two California detention camps and the frigid desolation of Heart Mountain in Wyoming. In quiet moments the watch would remind him of his years in the sunny orange groves of Azusa, but it also marked the hours and days that separated him from his family. For Wasuke was alone, removed from his wife, children and grandchildren because of the government’s policy on mixed-race families.

When President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 created a miliary exclusion zone along the West Coast, all persons of Japanese ancestry were forced from the region, including those with partial Japanese heritage.

“Included among the evacuees were persons who were only part Japanese, some with as little as one-sixteenth blood; others who, prior to evacuation, were unaware of their Japanese ancestry; and many who had married Caucasians, Chinese, Filipinos, Negroes, Hawaiians, or Eskimos,” the government’s final report stated.2

The Family Divided

Front row: Murray, Henry. Rafaela is pregnant with

Herbert. c 1928. Courtesy Hirota family.

The policy tore couples and families apart. Decades-long marriages were suddenly faced with the mandatory expulsion of a wife or husband of Japanese heritage from the West Coast. The removal orders affected biracial children in orphanages and single people of mixed-race parentage.

Wasuke and his wife, Rafaela “Rae” Martinez, a U.S.-born citizen of Mexican and Native American descent, had been married and living in Azusa for 27 years.

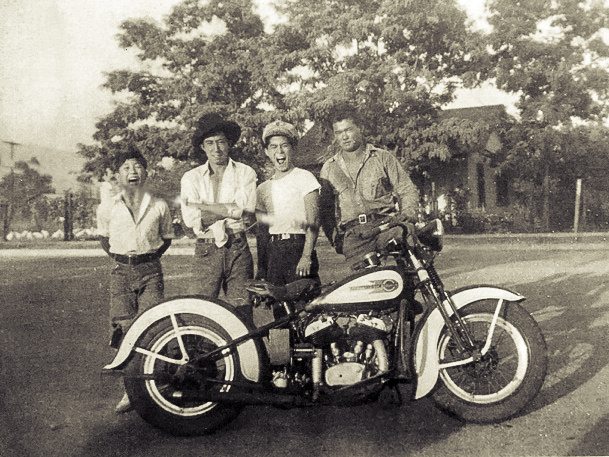

The couple had five children — Rose, 26; Louis, 24; Murray, 22; Henry, 19; and Herbert Hoover Hirota, 14 — and three grandchildren who were one-quarter Japanese: Lillian, 12; Paul 10; and Peter, 7.5

All except Rae were ordered to the Pomona camp. She accompanied Wasuke and the children anyway, unwilling to be apart from them. The “entire neighborhood was crying” when the Hirotas were taken away, recalls Inez Gutierrez, who was six years old at the time. She wondered where her neighbors were going.

Unbeknownst to the Hirotas, however, the government was in the midst of amending its policy on mixed-race persons. The changes would allow those who were half Japanese or less and “whose backgrounds have been Caucasian” to be considered for release from the camps if they were cleared by the intelligence services.”7

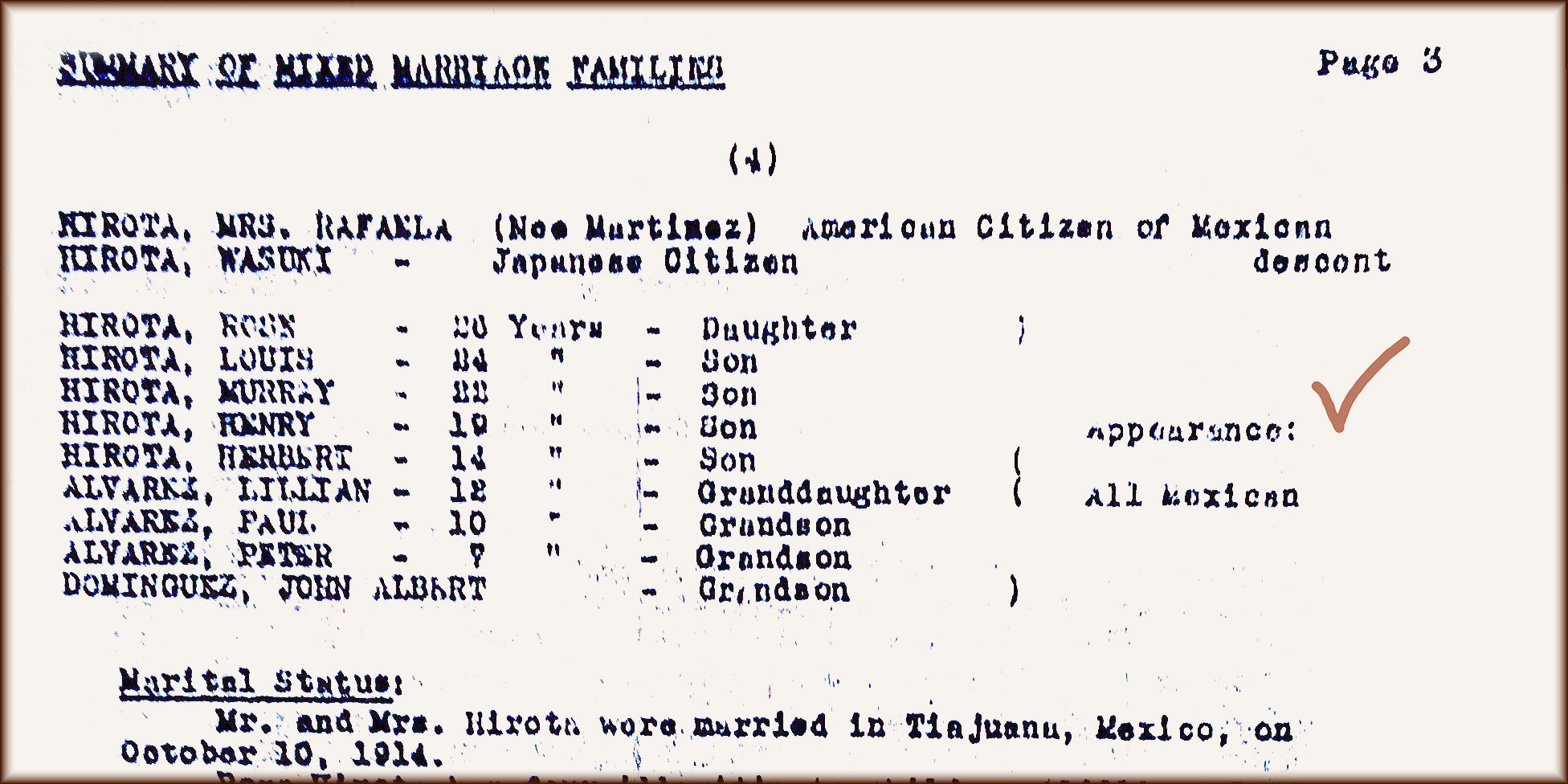

But how does one measure “Caucasian background”? That is the question addressed by a 1942 government report, “Summary of Mixed Marriage Families.” The 14-page survey8 profiles the Hirotas and 17 other interracial families at Pomona to assess their situation and confirm that candidates for release had sufficient “Caucasian background” to leave.

Mixed Race Policy

The report scrutinized personal choices in food, friends and social customs for evidence of cultural leanings, in some cases assigning percentages to show the degree of Japanese or Caucasian “influence.” Higher levels of “Caucasian” influence were equated with greater loyalty to the U.S. The Hirota children’s Mexican heritage was seen in a positive light.

The Hirotas “have associated entirely with Caucasians,” the report says. “The children speak only English and Spanish. Their diet is Mexican, and their customs, Mexican-American.” The children and grandchildren have the physical appearance of “all Mexican.”

“Mrs. Hirota and the children desire to return to their home at 329 Alameda Street, Azusa,” the report concludes. “Mr. Wasuke Hirota is willing to stay” behind.

Rae and the children were released.11 Wasuke, whose race superceded all, was moved to Santa Anita for 18 days and then to Heart Mountain, 1,000 miles away, in September, 1942.

Bring Him Home

Back in Azusa, family and friends began lobbying to bring Wasuki home. His former employer, C.A. Griffith, in a rare act of outside support for an incarcerated Japanese immigrant, wrote a letter to War Relocation Authority director Dillon S. Myer requesting Wasuki’s release.

“If Mr. Hirota is released from your camp, we will be very glad to give him steady employment as he is a valuable man and an expert irrigator. If we are competent to judge, and we should be, he is completely loyal to this country.”13

![]() Wasuke’s white neighbor, Frank Tarble, a World War I veteran, wrote eight letters over a period of two years to government officials, requesting Wasuki’s release. “I will stand parole for him, even to furnishing a bond if necessary,” he wrote.14

Wasuke’s white neighbor, Frank Tarble, a World War I veteran, wrote eight letters over a period of two years to government officials, requesting Wasuki’s release. “I will stand parole for him, even to furnishing a bond if necessary,” he wrote.14

The appeals were rejected as were Wasuki’s requests to be transferred to Poston (AZ) and Manzanar (CA), camps closer to home.

On October 31, 1944, Wasuke wrote to the Western Defense Command, requesting a form. Four days later, he died of heart failure.

“He left us walking and came home in a box,” Rae was to say for years after.17

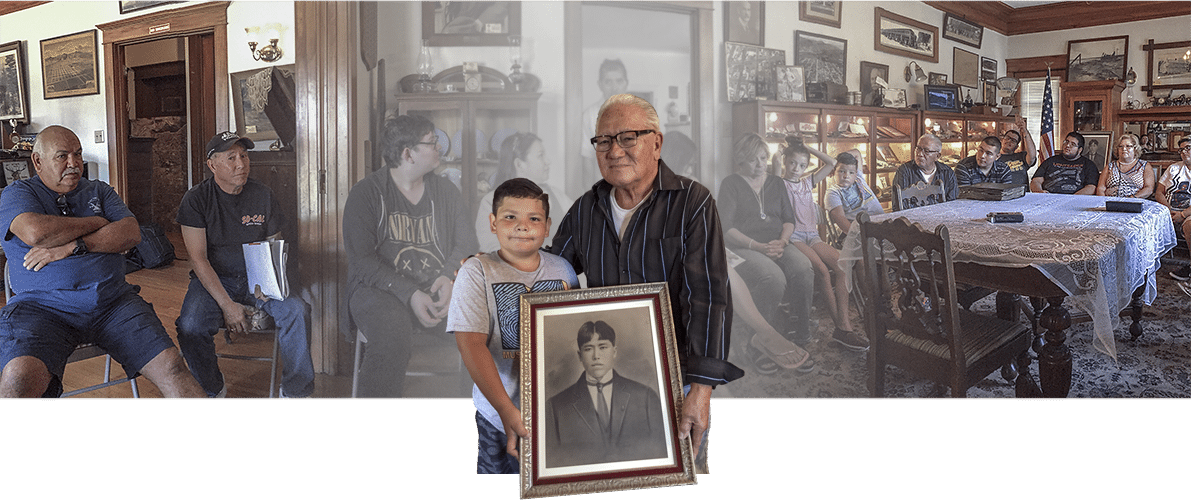

Remembering Wasuke

In the summer of 2017, four generations of descendants and relatives gathered at the Azusa Historical Society to remember Wasuke. They talked about the koi ponds he built in Azusa and laughed about memories of pounding mochi rice at New Year’s.

There have been no more marriages to people of Japanese descent but the Hirota family name lives on. Louis V, age 10, the great-great-great grandson of Wasuke, once asked his great-grandfather, “why is my last name Hirota?” He attended the meeting so that he could hear the stories that honor his heritage.

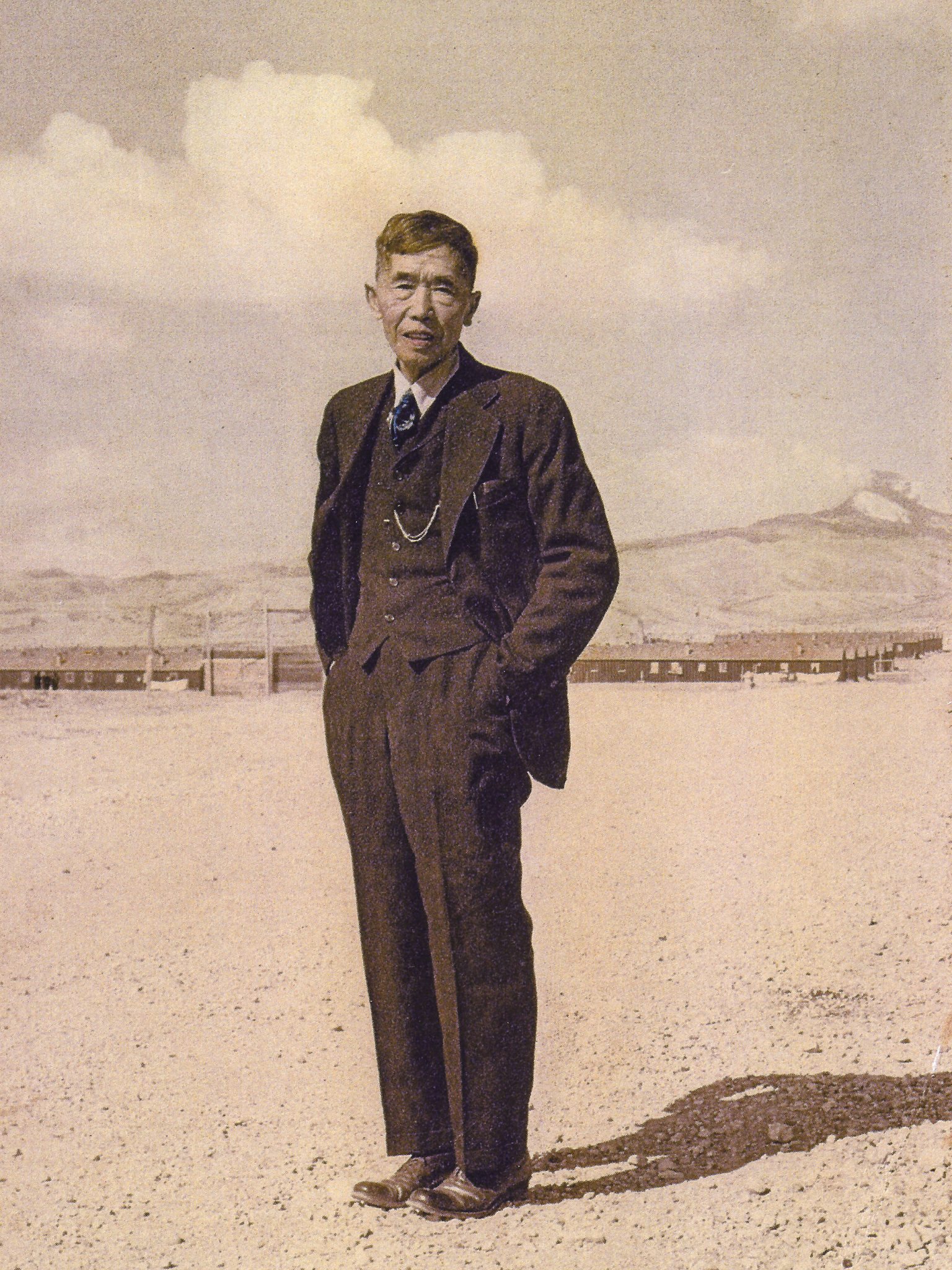

Photos of Wasuke at Heart Mountain were passed around in a circle. A colorized photograph shows him standing before rows of barracks with Heart Mountain in the distance. He is dressed in a three-piece suit with a watch chain draped across his vest.

Hands in pockets, he looks dignified and somehow removed from his surroundings.

After the meeting ended, Louis Jr. unwrapped his grandfather’s gold pocket watch. In preparation for the family gathering, he had wound the timepiece the night before. “I was afraid to wind it,” he said, unsure of its condition. But “lo and behold, the second hand started working. It still keeps time.”

| Wasuke's Gold Watch | |

|---|---|

| dimensions | 1.57 in. x 2.27 in. x 1.2 in. |

| material | 14k gold, glass, metal |

| date | c 1942 |

| creator | Waltham Watch Company |

| presented | Gift from Azusa Foot-Hill Citrus Co. to Wasuke Hirota, spring 1942, Azusa, CA |

| family history | Given by Rae, Wasuke's widow, to oldest son Louis. Handed down to Louis Jr. |

| photo, measurements | Louis HIrota Jr. |

References

Garcia, Matt. 2001. A World of Its Own: Race, Labor, and Citrus in the Making of Greater Los Angeles, 1900-1970. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Orenstein, Dana. 2005. Void for Vagueness: Mexicans and the Collapse of Miscegenation Laws in California. Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 74, No. 3, 367-408. Background to the case Perez v. Sharp (1948) which was the first court ruling in the U.S. to overturn a miscegenation law.

Credits

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: Saya Russell, Nancy Ukai and Dave Meiklejohn courtesy of the Pomona Progress-Bulletin 4/1942

Special thanks to:

Raymond Alvarez, Louis Hirota Jr., Louis Hirota V, Larry Hirota, Marcus Fino, Linda Reyes, Inez Gutierrez, the Hirota family, Dale Martin, Azusa Historical Society, Sara Butler-Tongate, Library and Research Center of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors

Supported in part by The National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program