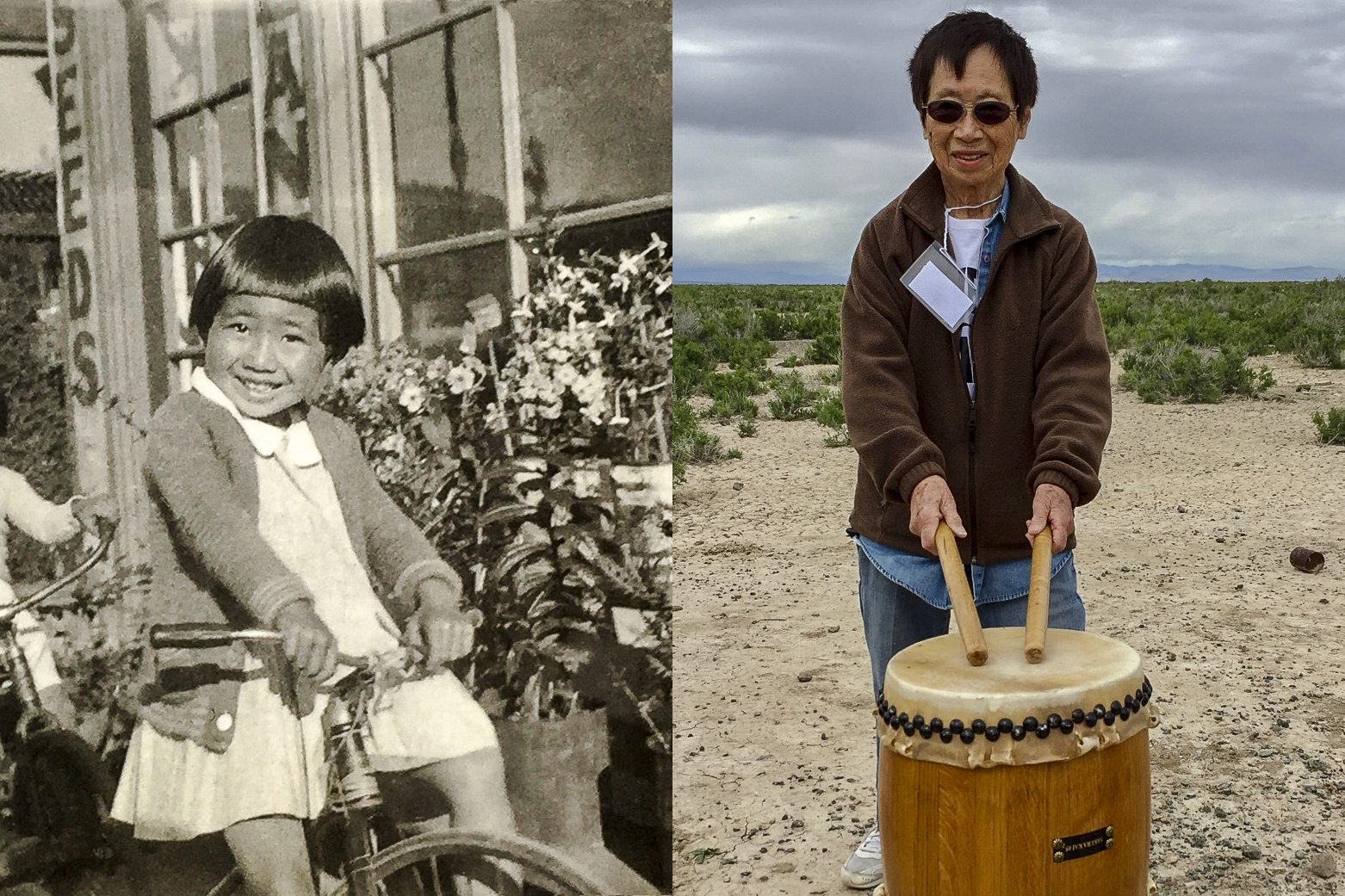

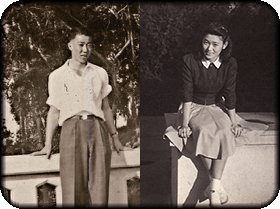

It was love at first sight when Michiko Fujii, 18, and George “Ki” Kiyoshi Uchida, 20, met as undergraduates at U.C. Berkeley in 1940. “That was it,” Michiko said. 1 The two dated exclusively and planned to get married after she graduated.

But “9066” changed their plans, she said, referring to President Roosevelt’s executive order that would remove all American Japanese from the West Coast under the guise of military necessity. Worried that they might be separated to different prison camps, they decided to marry immediately. On Monday, April 27, 1942, Michiko and Ki were wed by Reverend Nishimura at her parents’ home on Harper Street in Berkeley.

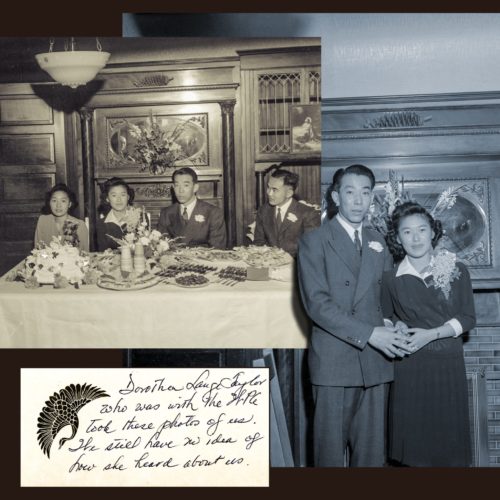

The family had relinquished their cameras, which were considered contraband, to the government in accordance with the military’s instructions, so they were unable to take wedding photos. However, in the midst of the family wedding party, a stranger appeared at the door. No one remembered how the arrangements had been made or how the stranger knew of the nuptials, but a white photographer from the government, who had asked in advance for permission to take photos, duly showed up with an assistant, took a few pictures and left.

Michiko thought to herself, “That’s it, everybody else in our family got married and they got their picture taken, but we’re never going to get (a copy).”2

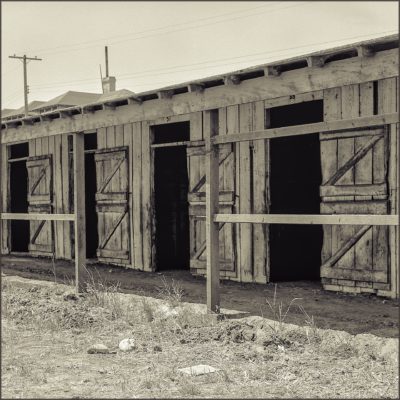

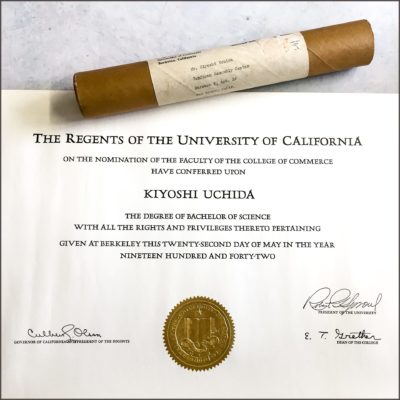

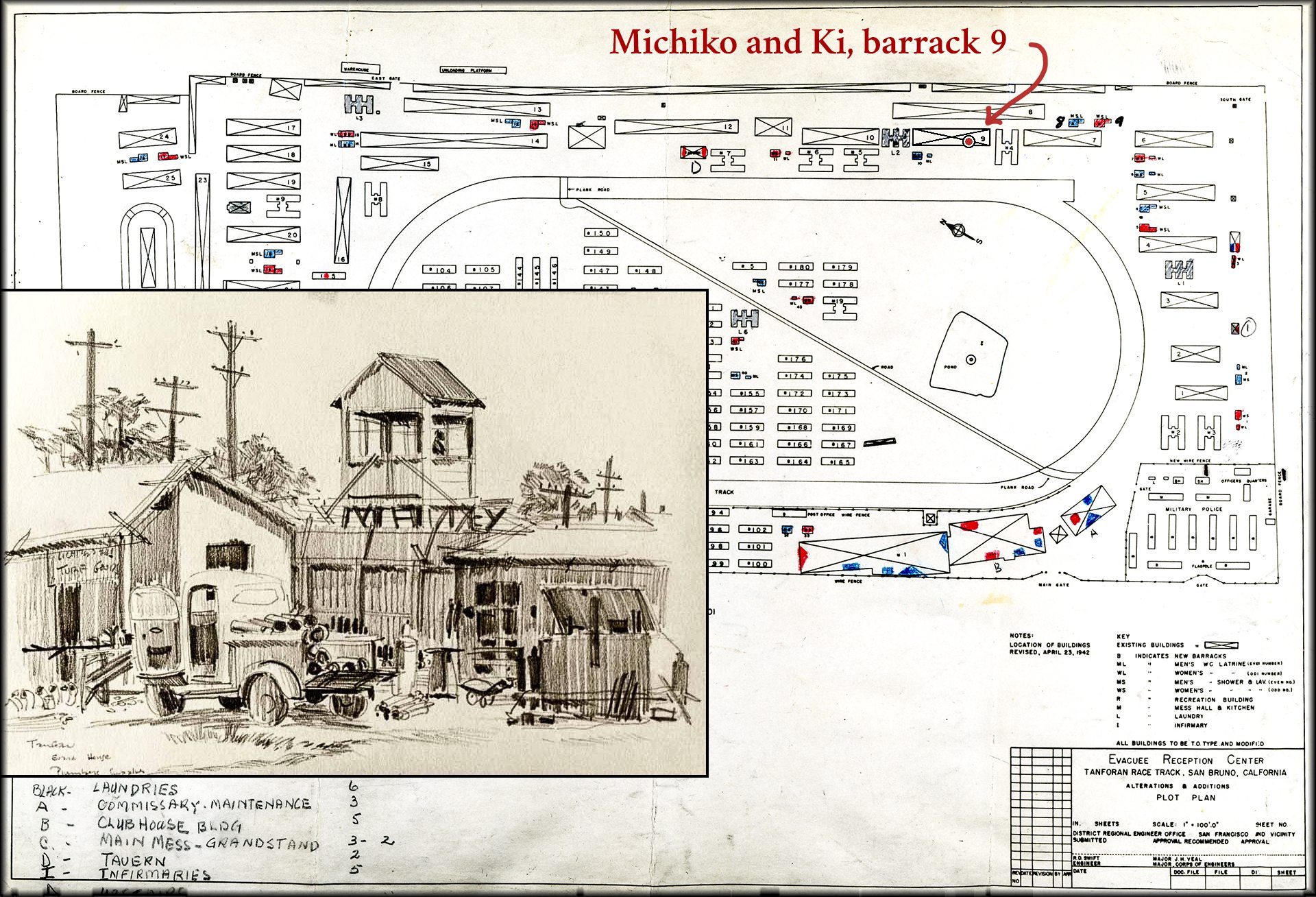

Forty-eight hours later, the couple were assigned to barrack 9, cell 16 at the Tanforan Race Track in San Bruno. They had their honeymoon in a horse stall. Michiko remembers eating off pie tins and sitting in the upper section of the stable. From there they could see the infield and the viewing stands under the watch of armed sentries and searchlights. Ki, who had been a senior in the class of 1942, received his diploma in a mailing tube addressed to the stable.

Five months later, in October, 1942, Michiko and Ki were taken with 500 men, women and children on a train to the small town of Delta, Utah, near the desolate Topaz site. It was in the midst of a sandstorm and Michiko was suffering from heat prostration. She was moved by bus to the Topaz camp, where she was assigned to a barrack and collapsed on a military cot. When she woke up, her body was caked with dust and the silhouette of where she had lain was outlined by sand.

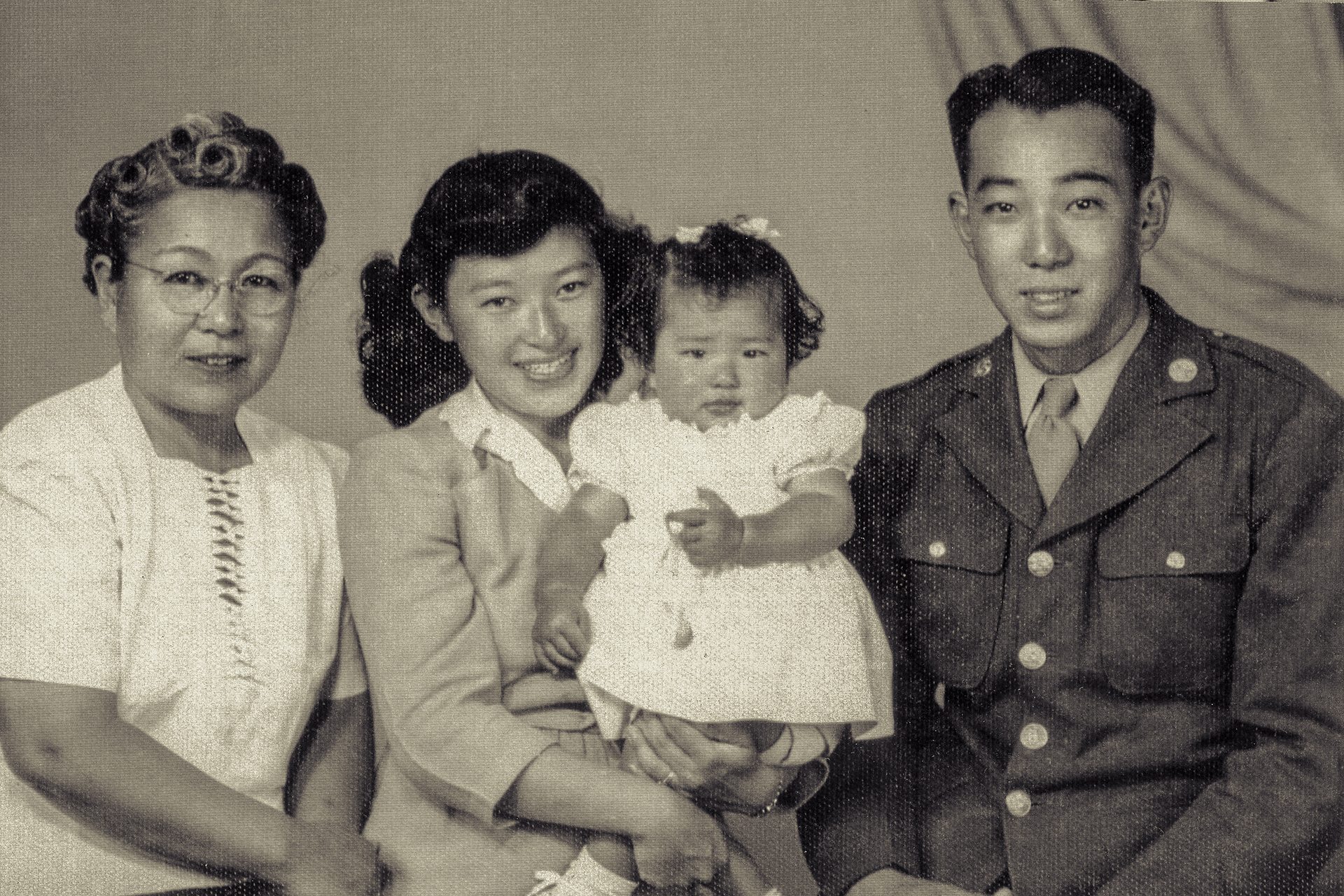

During three years behind the fence at Topaz, Michiko gave birth to two baby girls. Without running water, her days were filled with carrying buckets of water from the communal washroom to the barracks. Ki was drafted into the U.S. Army and visited his young family in camp on furloughs from the Military Intelligence Service.

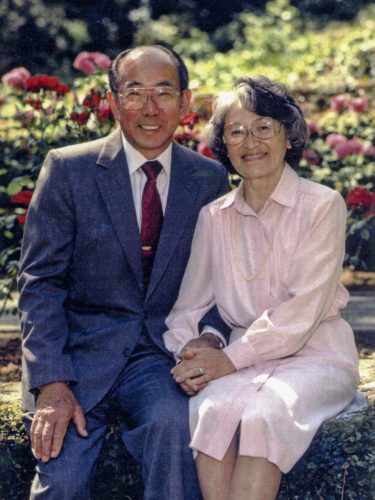

After the war, Michiko and Ki moved back to Berkeley. The couple raised four daughters and after the girls were mostly grown, Michiko returned to U.C. Berkeley and completed her degree at age 44.

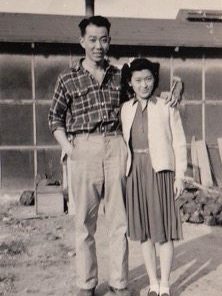

On the occasion of her sister Yuri’s 50th wedding anniversary, in 1958, Michiko was asked to make a commemorative album using the siblings’ wedding photos. Not having a photo of her own hurried ceremony, Michiko was forced to make do.

She found a snapshot that had been taken of the couple at Topaz while Ki was visiting on furlough, but there was a problem: Michiko was holding a baby. She decided to carefully snip the baby out, creating a doctored photo of herself and Ki. “I felt kind of bad, but that’s the way it was,” she said. This would suffice as her “wedding photo.”

Not long afterward, the couple’s friend, Tom Kawaguchi, who had been doing research on military history in Washington, D.C. for the Go For Broke organization, said to her and Ki, “I think I saw your wedding picture at the National Archives.”

The couple had, coincidentally, just returned to the Bay Area from a visit to Washington, but excited to hear this unexpected news, they hurried back to the archives where they located two government photographs of their home wedding.

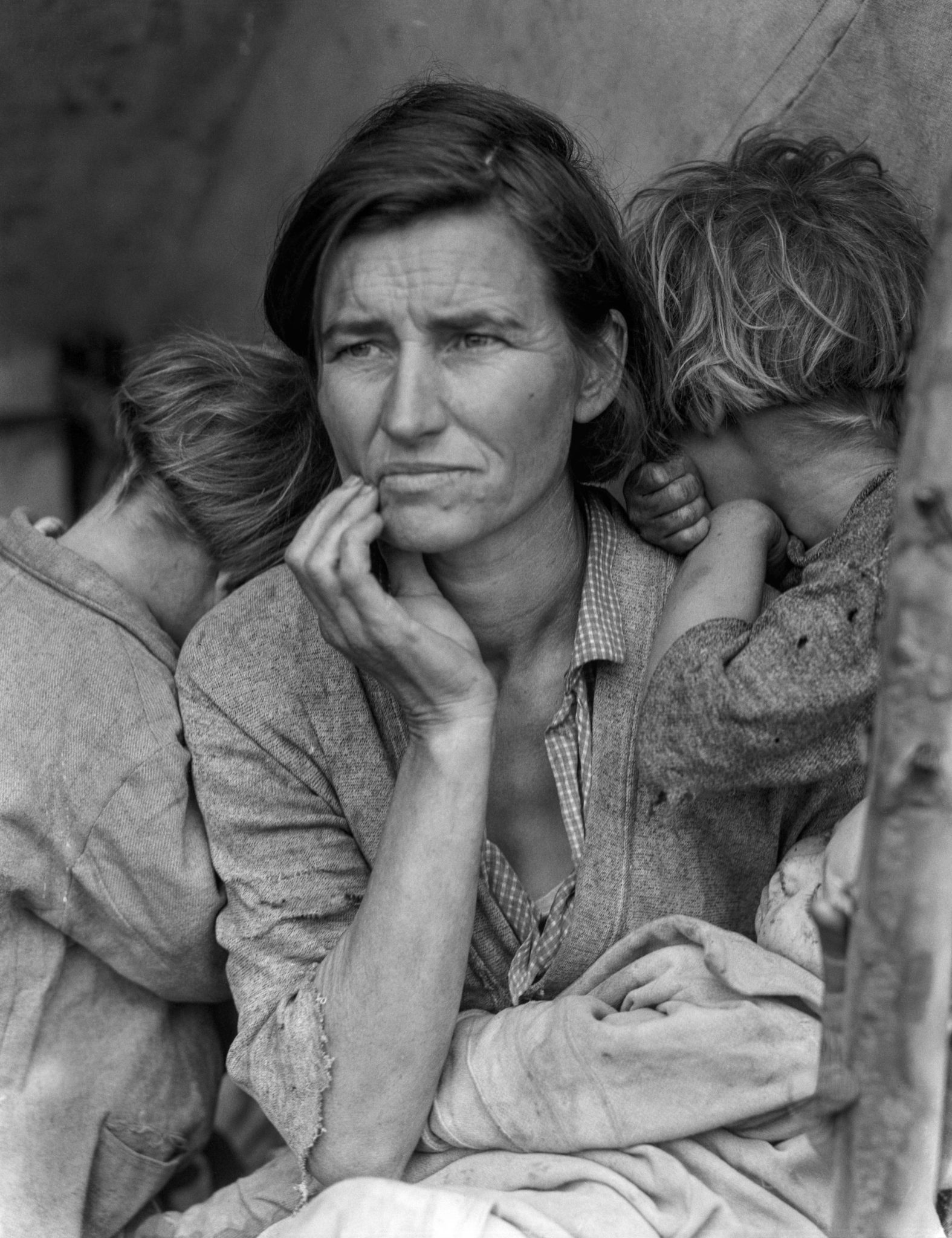

The photographer was Dorothea Lange.

Although Lange is celebrated for her immortal photographs of the Depression, Dust Bowl refugees and the American Japanese incarceration, for Michiko and Ki, she was their wedding photographer. She memorialized a day when they didn’t have a church wedding or much of a celebration; many of their friends lived more than five miles away, the allowable zone for American Japanese to travel without a permit.

Lange herself was in the midst of documenting the government roundup and removal program as a War Relocation Authority photographer. She had been working nonstop, photographing evictions all over central and northern California. She also documented assembly center prisons at Sacramento, Salinas, Stockton, Tanforan and Turlock. Most of her photos, which were seen by wartime censors as uncomplimentary, were impounded and withheld from the public during World War II.

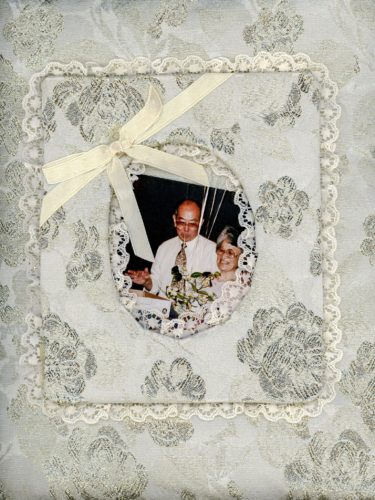

Michiko and Ki’s wedding photos were found shortly before their 45th anniversary. Now they are preserved on the pages of their 50th wedding anniversary album.

| The Photos | |

|---|---|

| photographer | Dorothea Lange, War Relocation Authority |

| dinmensions of Uchida prints | 7 1/2" x 7 1/2" |

| place | 2903 Harper Street, Berkeley, CA |

| date | April 27, 1942 |

| collections | 1. National Archives RG 210-G-C343, 537680 (photo of couple); 537681 (family at table); 2. Uchida family collection. |

| photo: page from the Uchidas' 50th wedding anniversary album | |

Dorothea Lange – photographer

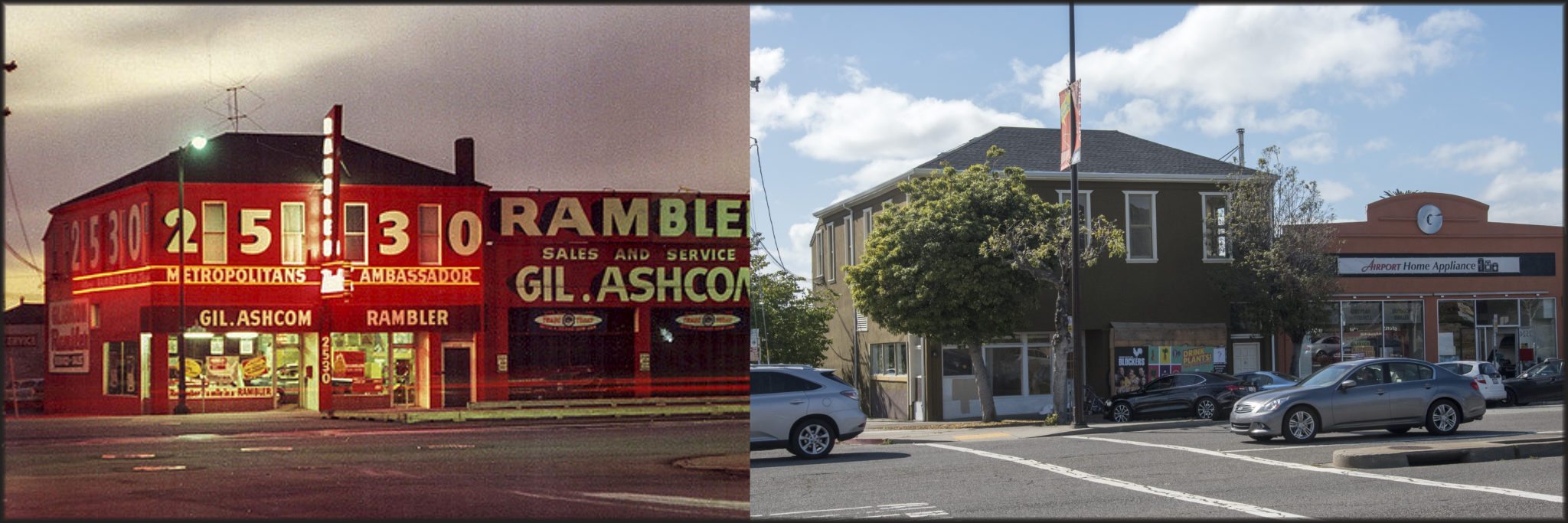

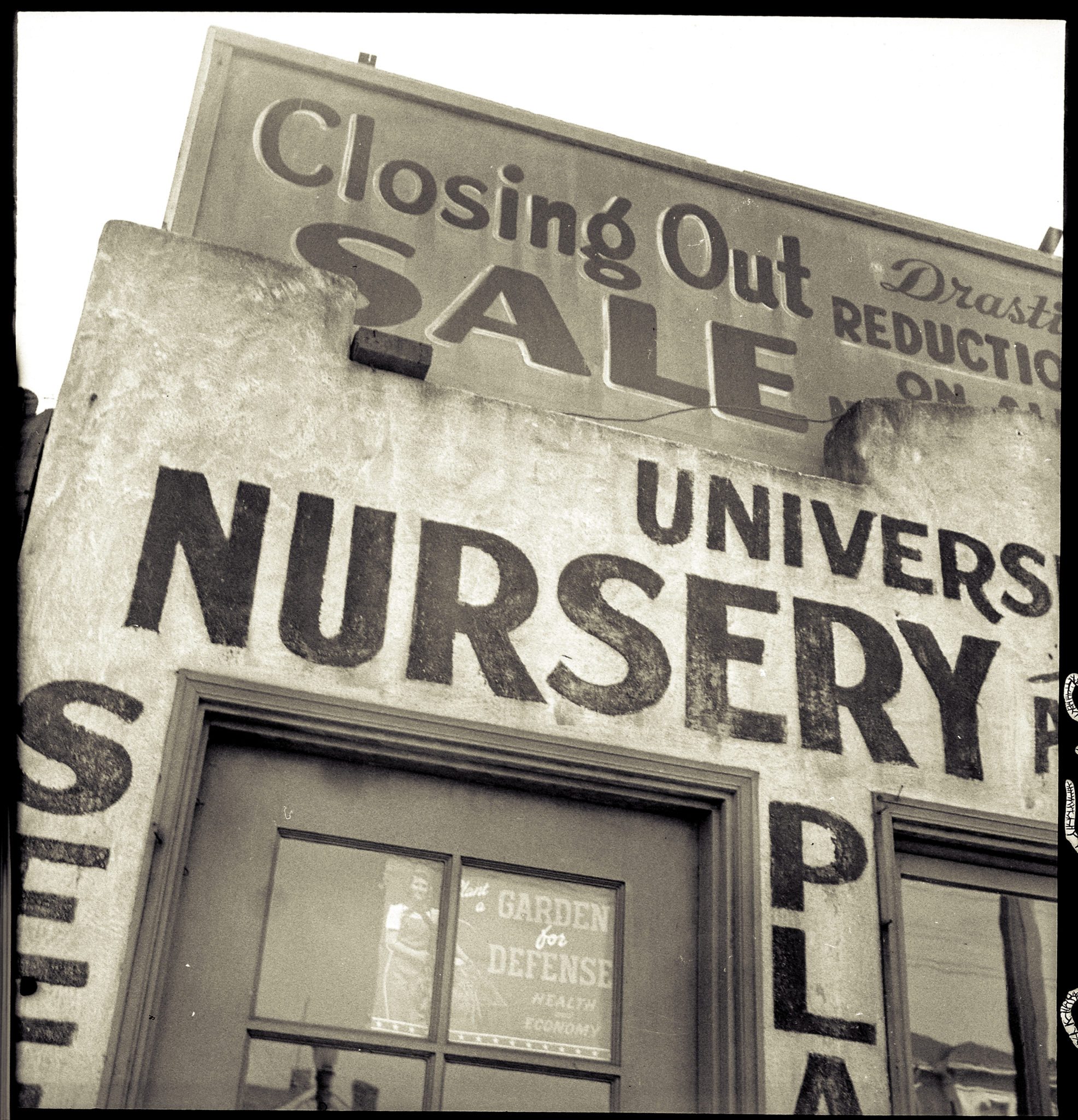

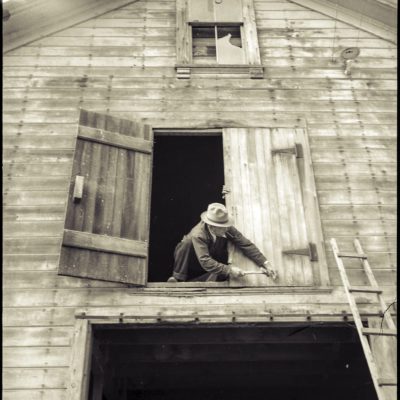

The Uchida wedding photos were taken in late April, 1942, about one month after Lange signed a three-month contract with the WRA.10 She documented the packing, sales, and shutting down of businesses, homes and farms in urban and rural communities in central and northern California despite harrassment from the military which was overseeing the roundup and expulsion. Even the WRA, which had hired her, “were at times suspicious of what she was doing” and “restrictions surrounded her as she worked: no pictures of the barbed wire or watchtowers or armed soldiers guarding the camps.”11 Lange was dismissed on July 30, 1942. The photos below were taken over an eight-day period in May, 1942.

Credits

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

cover images: Dorothea Lange (coloring added by David Izu), Nancy Ukai, other photos courtesy of the Uchida family

Special thanks to:

Michiko Uchida, Leslie Tsukamoto, Kazuko Iwahashi, Richard Cahan, Steve Finacom, California Historical Society.

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service,

Japanese American Confinement Sites program