Twenty-one-year-old Bette Okajima, far from home in a desert prison, turned to the last page of a government questionnaire whose answers would determine her chances for early release.

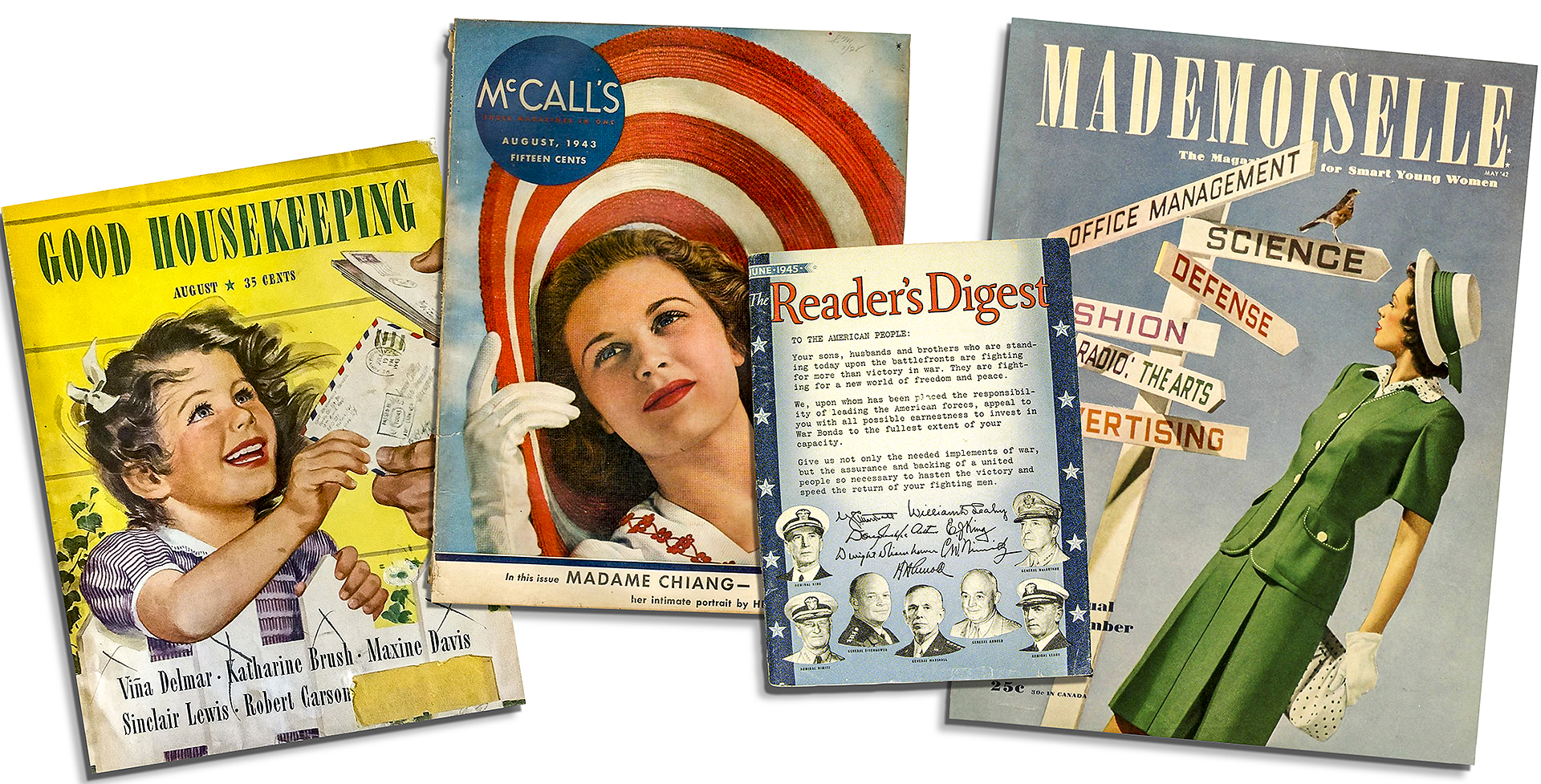

Question No. 24 instructed: “List magazines and newspapers to which you have subscribed or have customarily read.”

In her neat cursive, Bette wrote: “Reader’s Digest, McCall’s, Mademoiselle, Good Housekeeping, Fresno Bee.”

Three were women’s magazines, the Fresno Bee was her hometown daily and Reader’s Digest was the nation’s best-selling periodical.

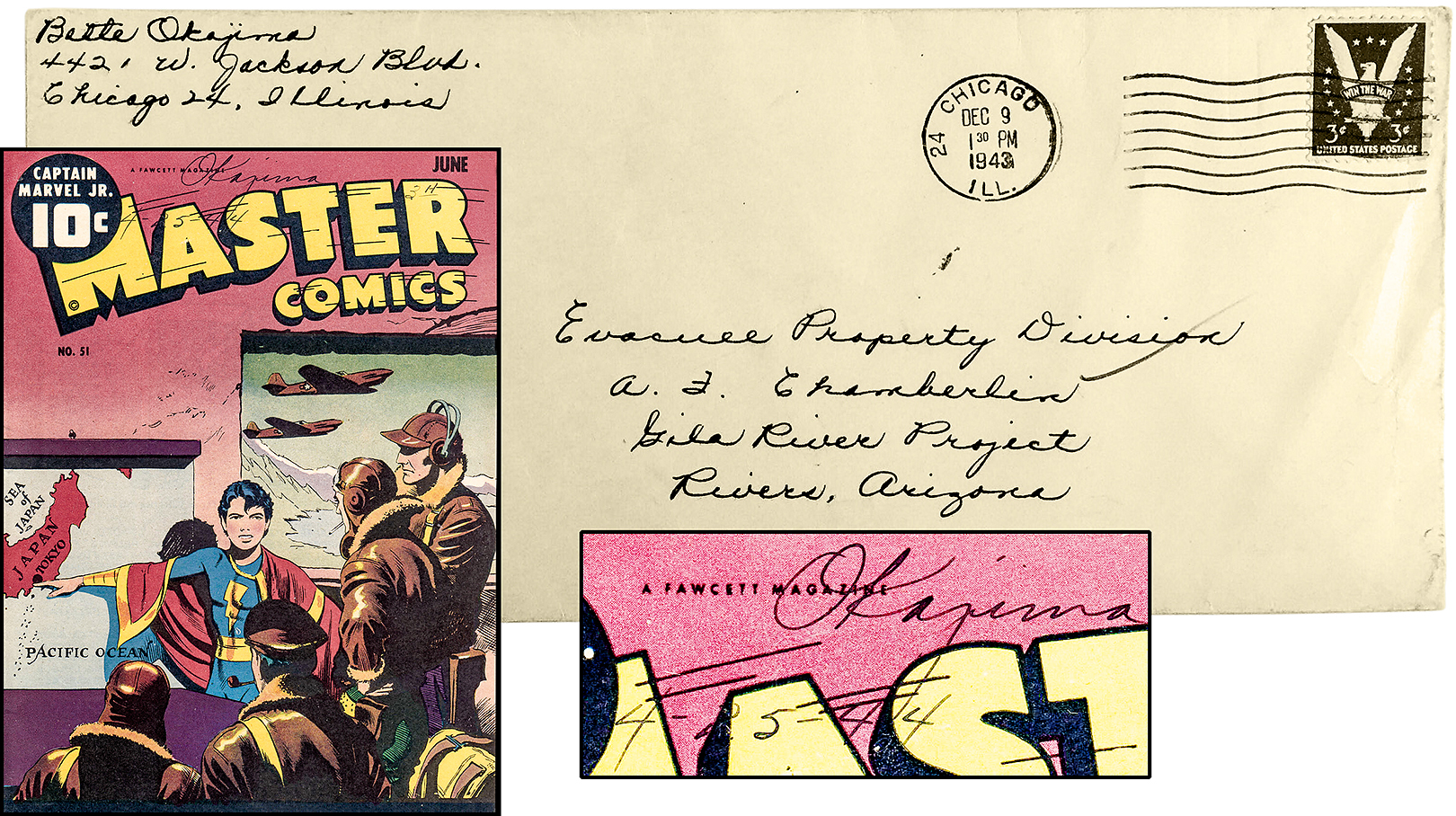

Bette finished the questions, signed her name and filled in the date: August 10, 1943.1 But maybe she hadn’t told the full story. Or perhaps she was telling the review board what she thought they wanted to hear.

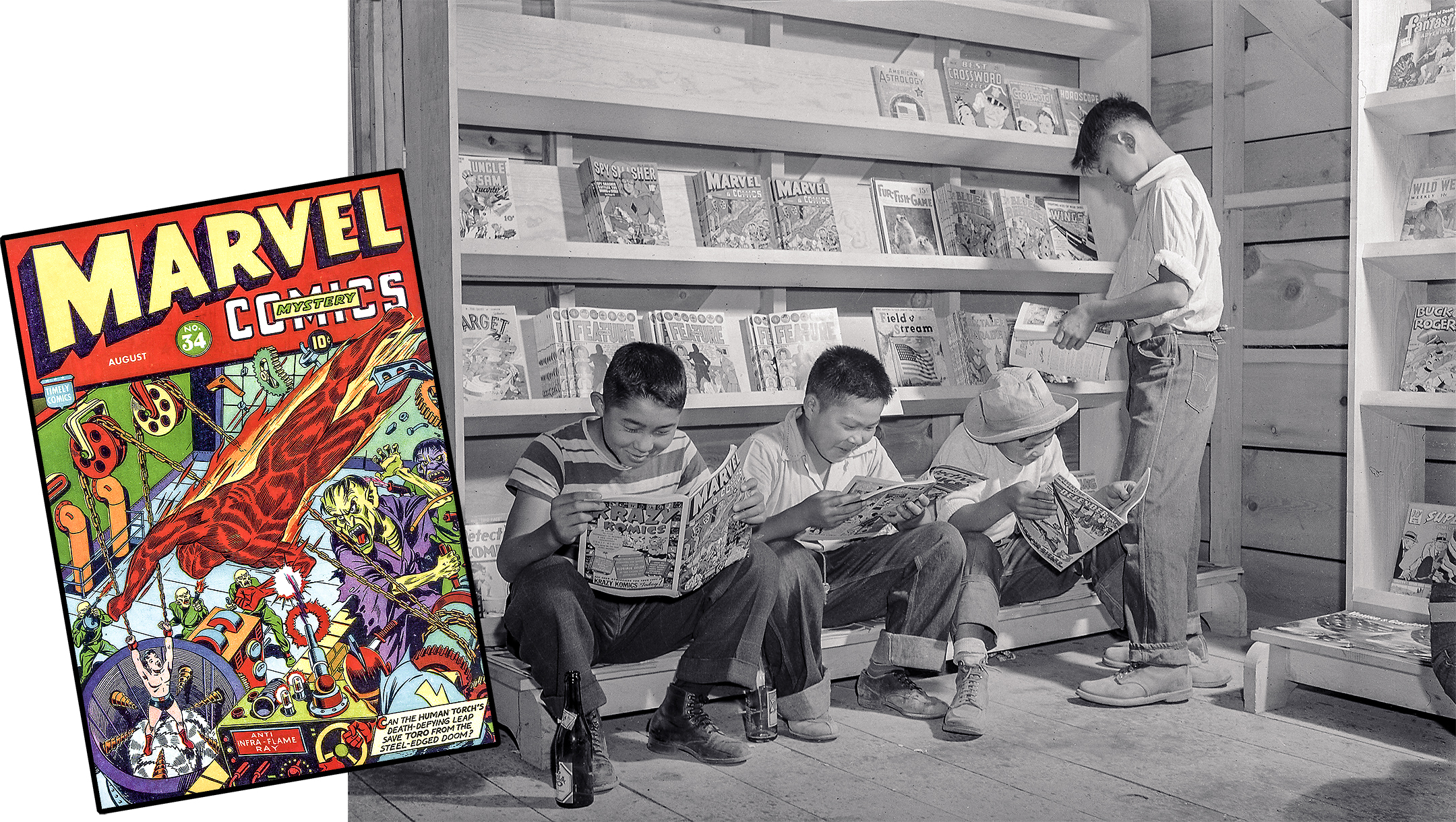

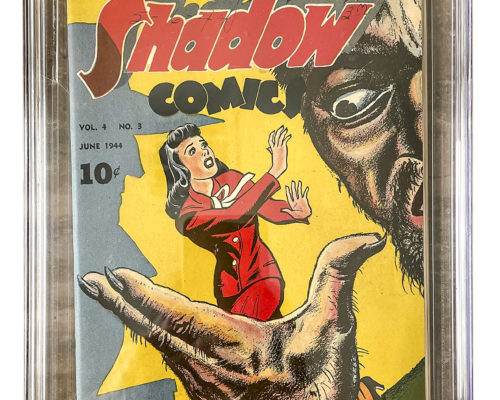

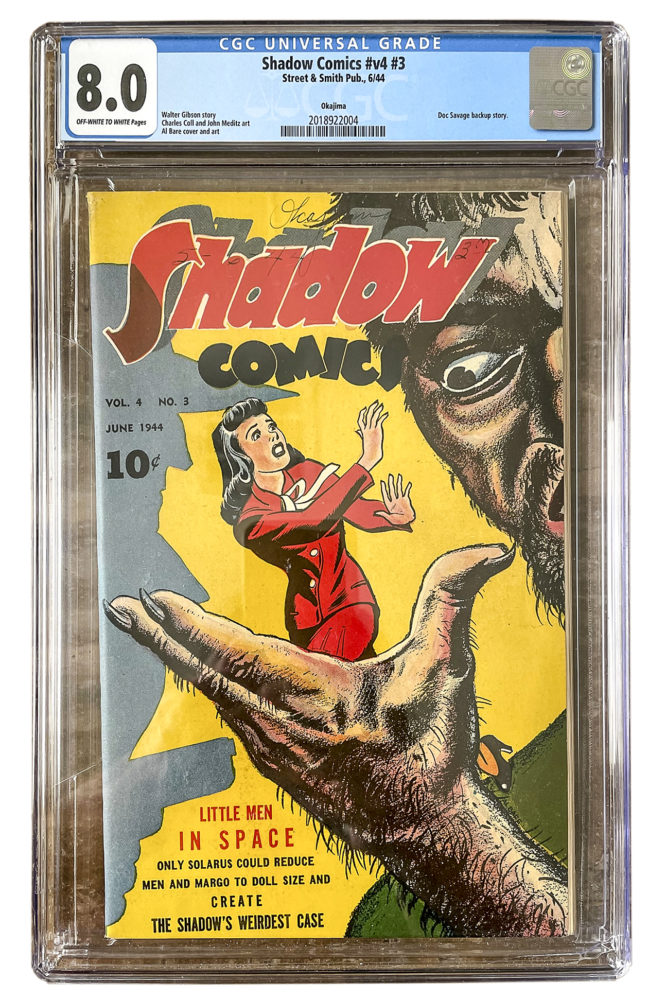

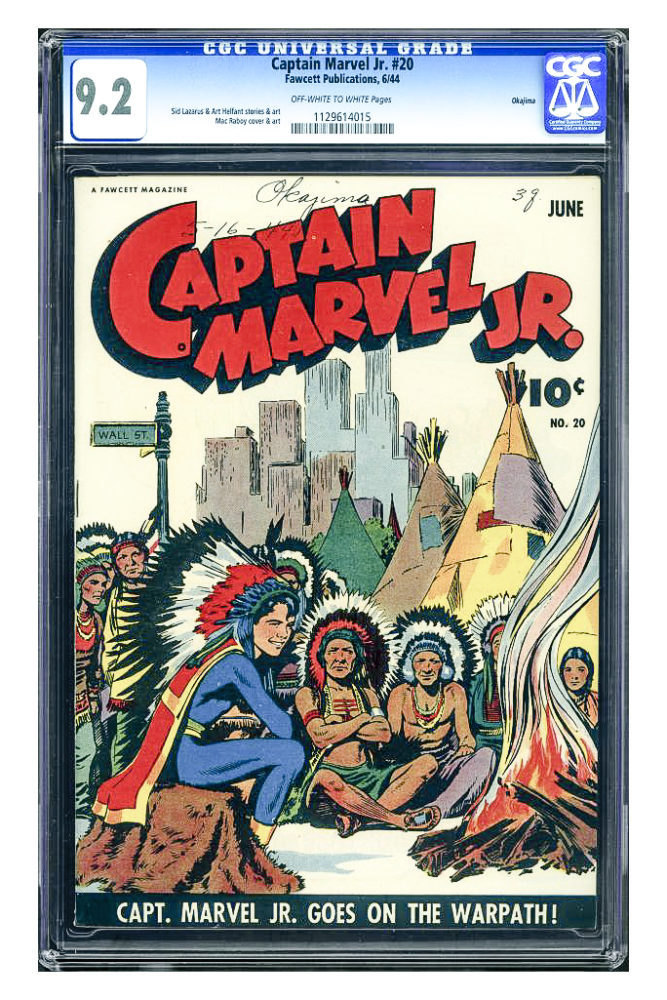

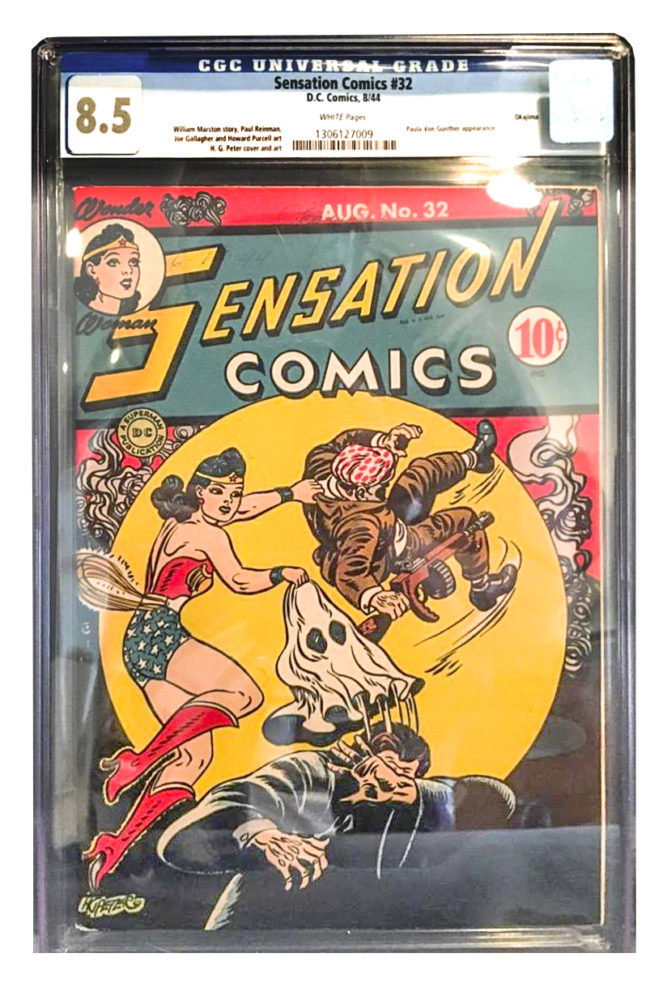

Mild-mannered Bette — five feet tall and 95 pounds, with wavy hair and eyeglasses — actually loved reading superhero comics: action-packed, violent, fantasy pulps.

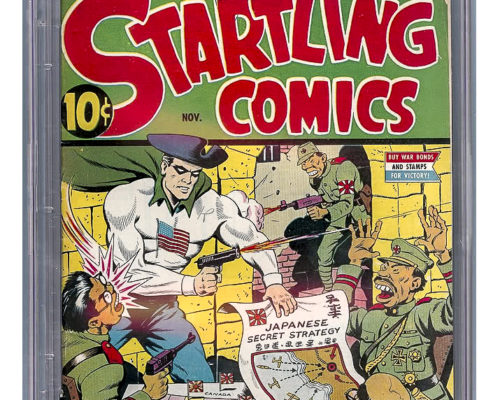

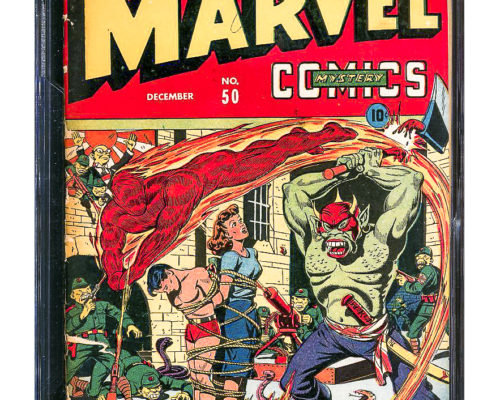

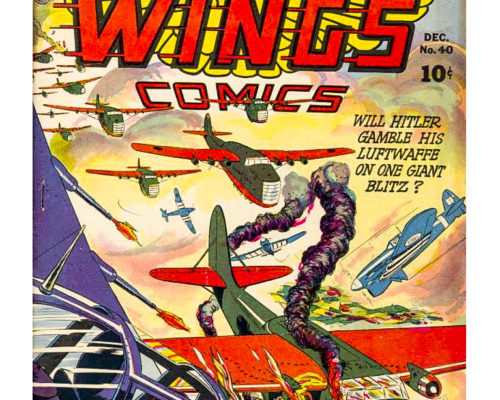

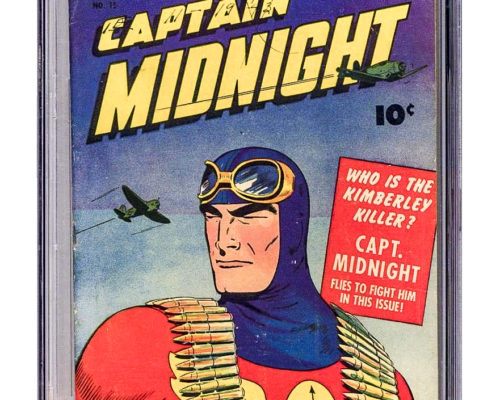

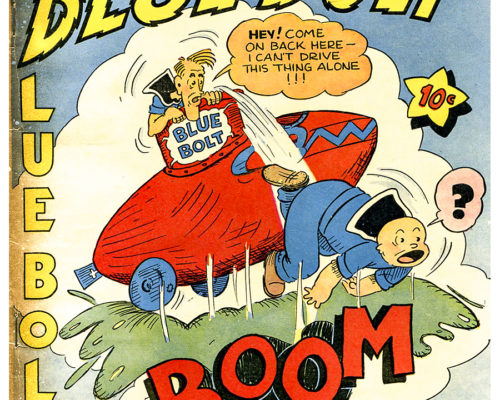

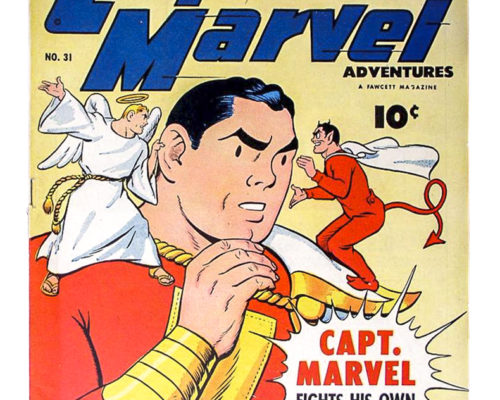

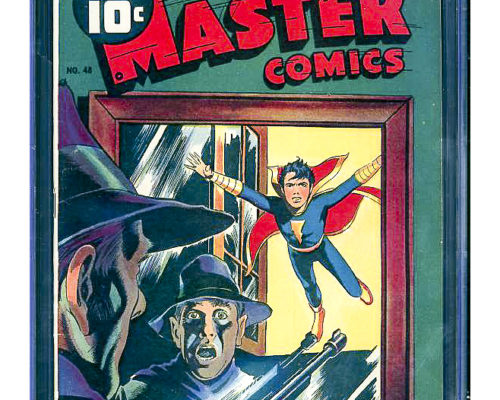

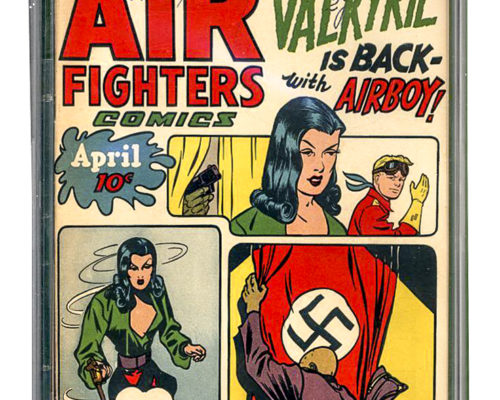

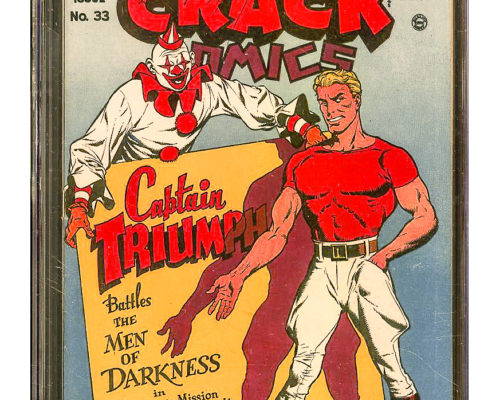

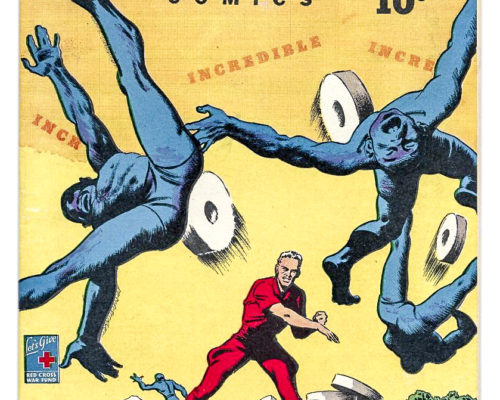

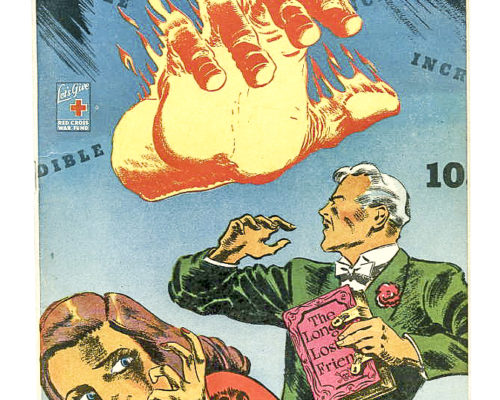

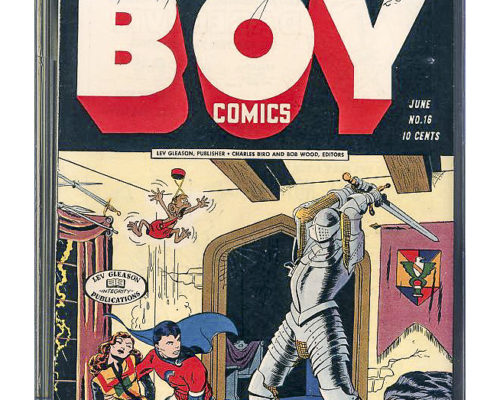

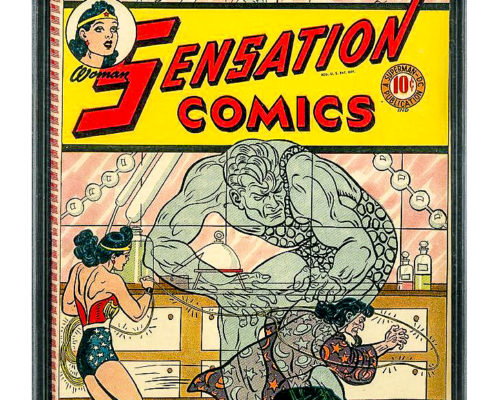

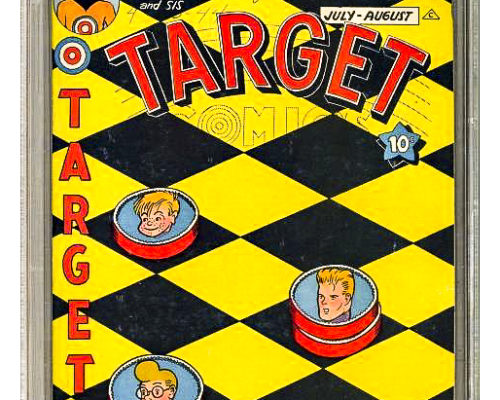

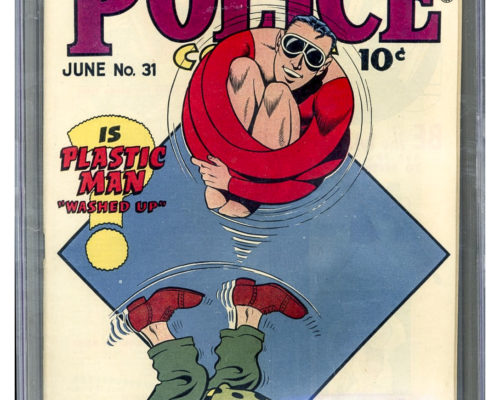

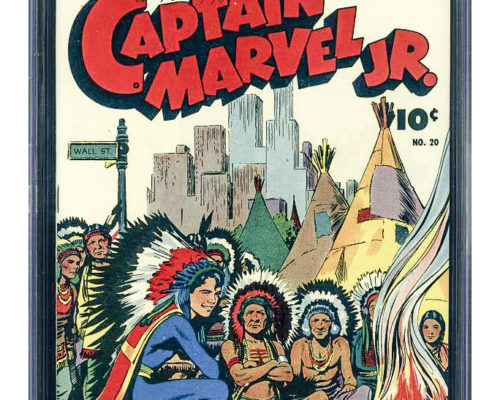

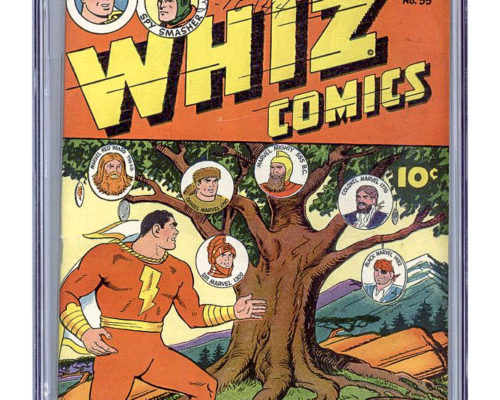

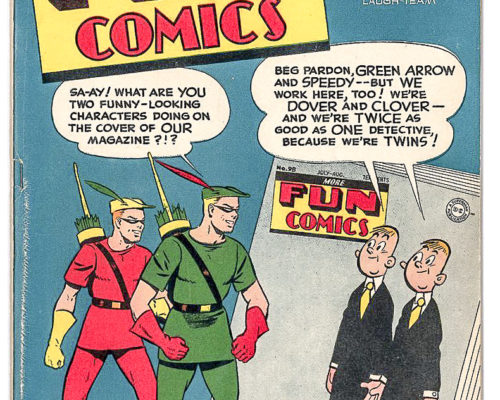

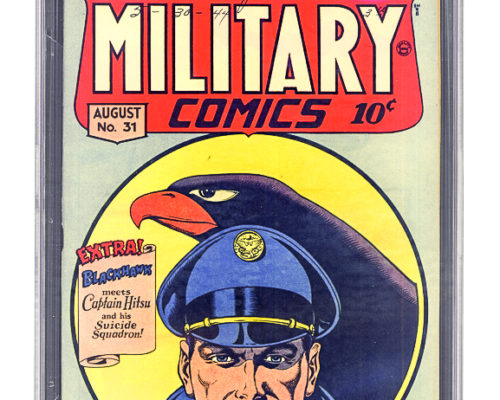

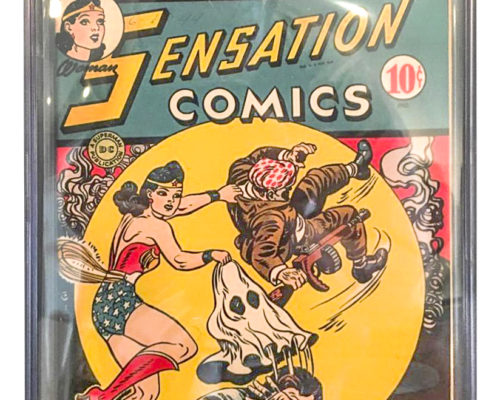

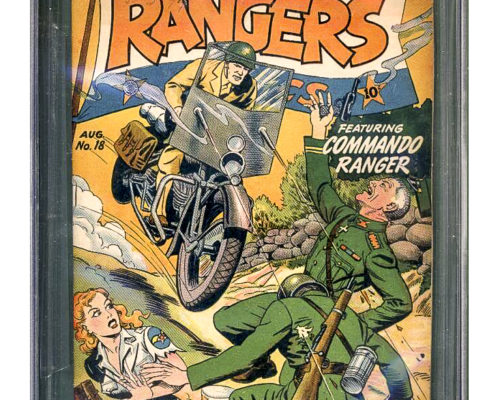

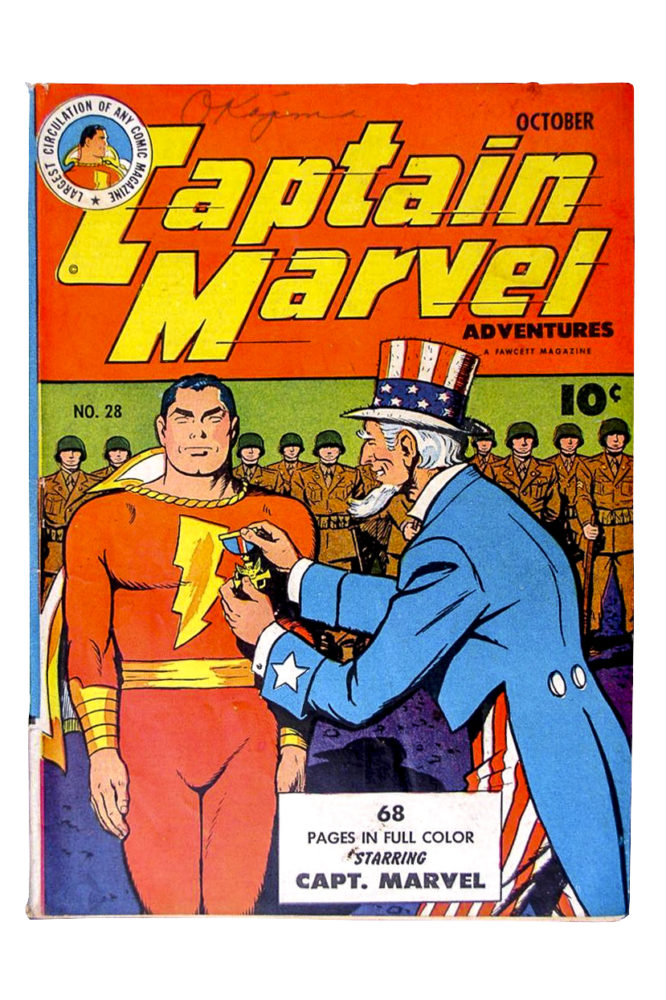

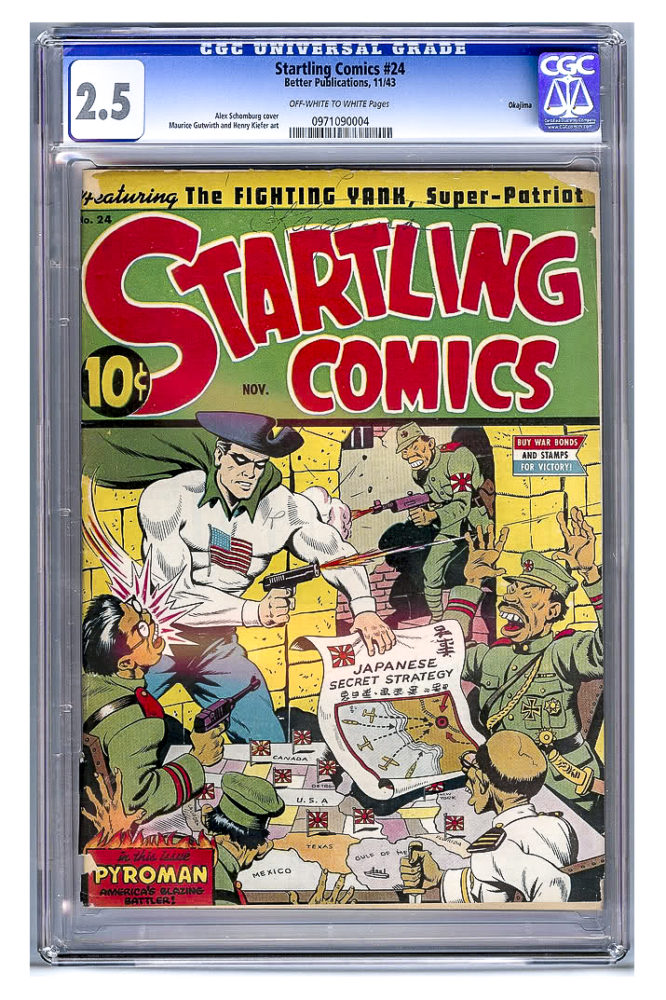

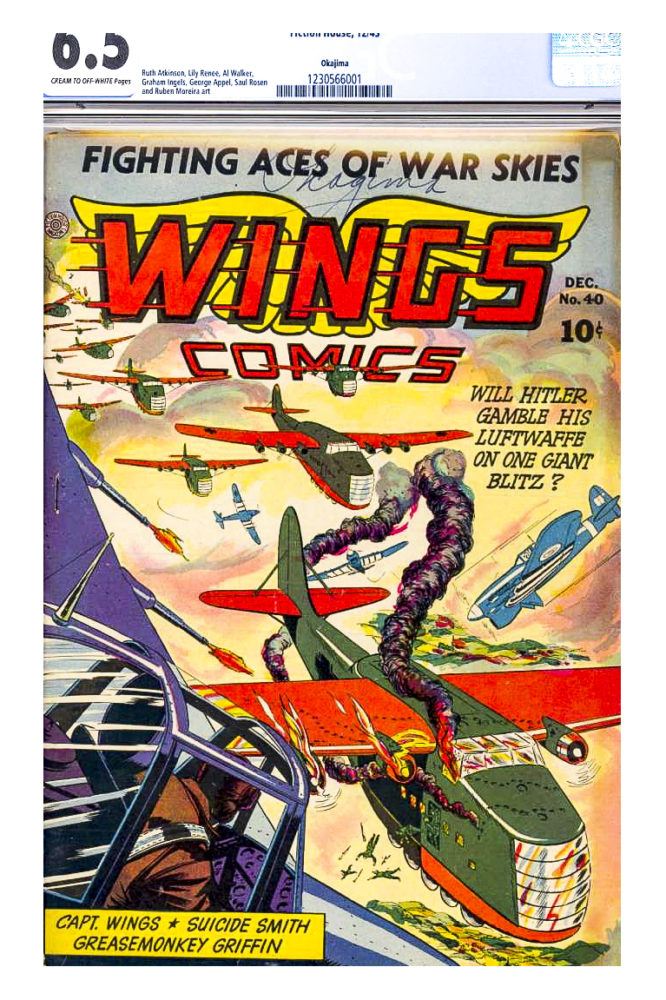

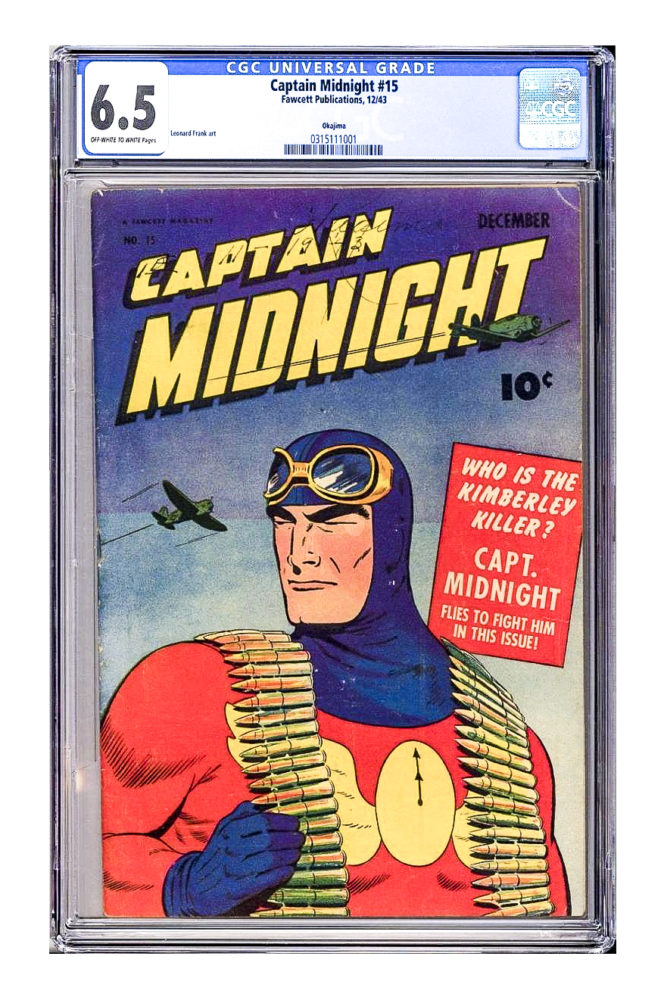

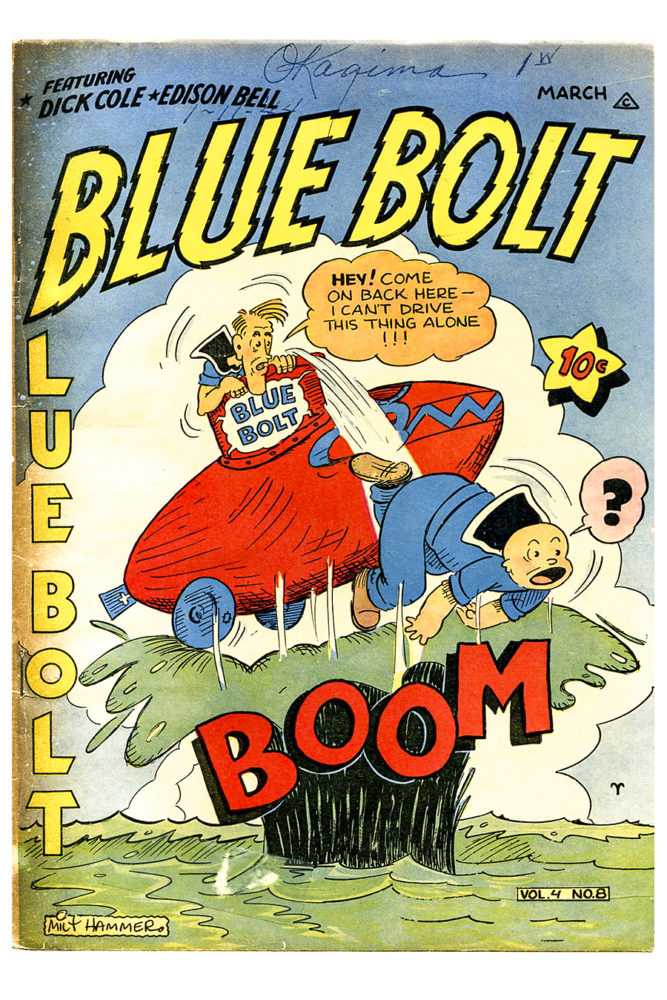

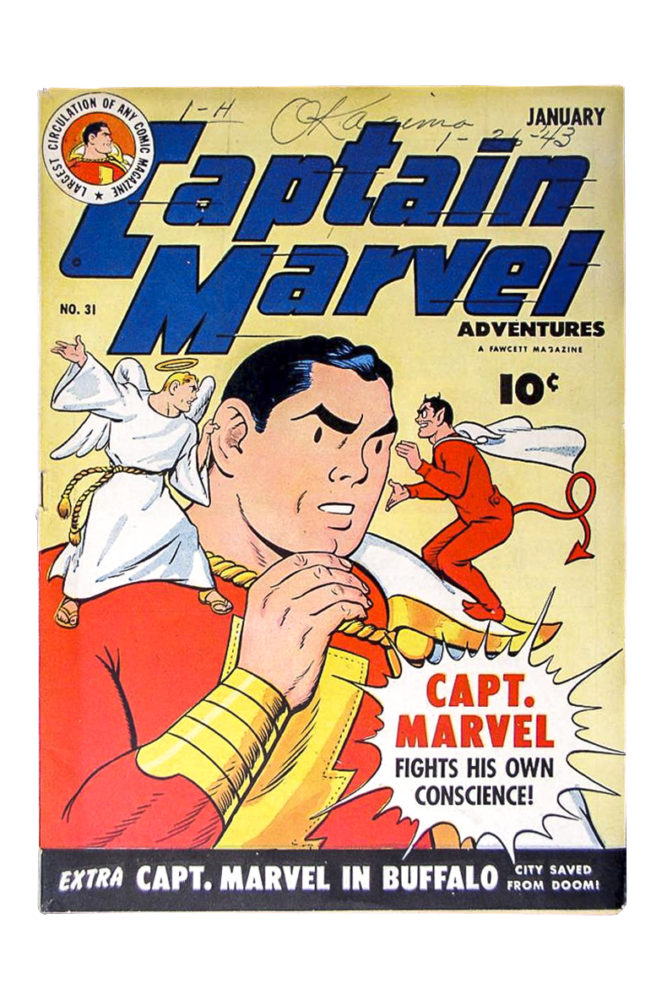

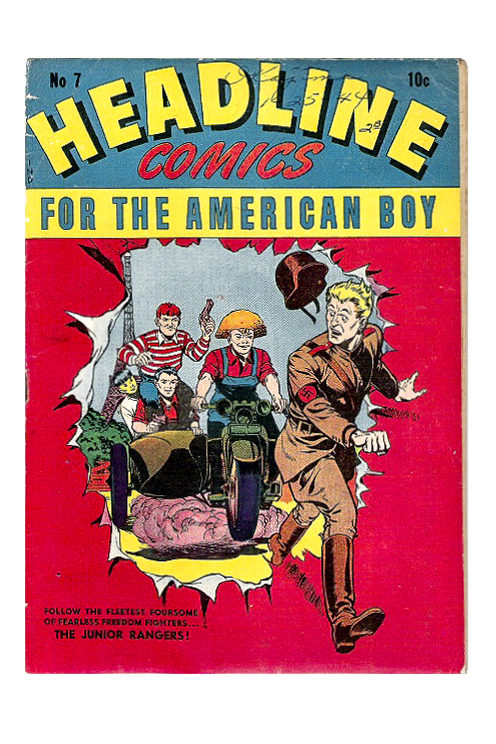

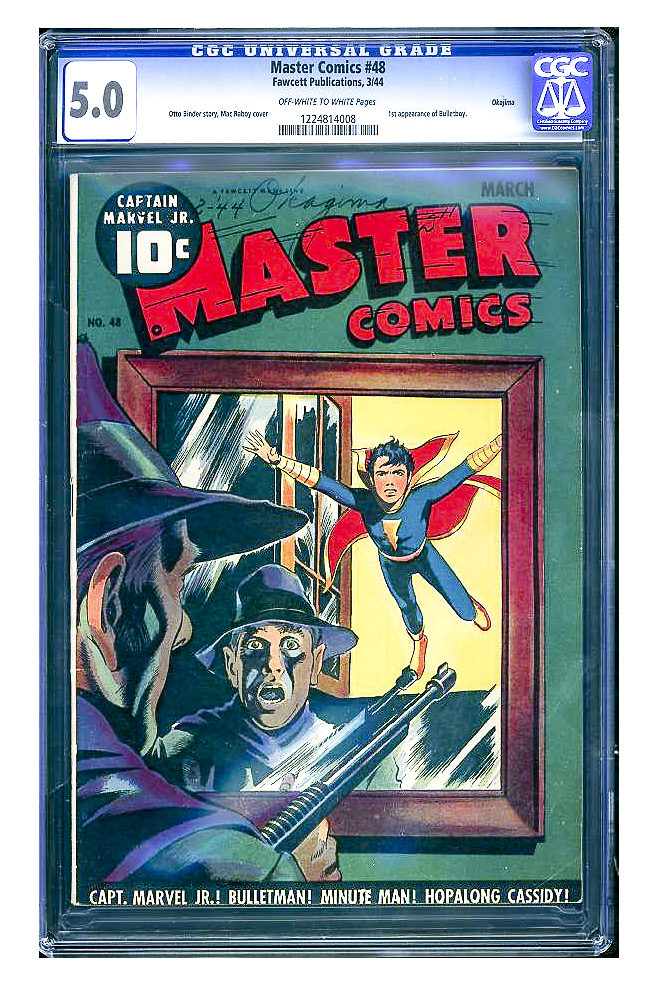

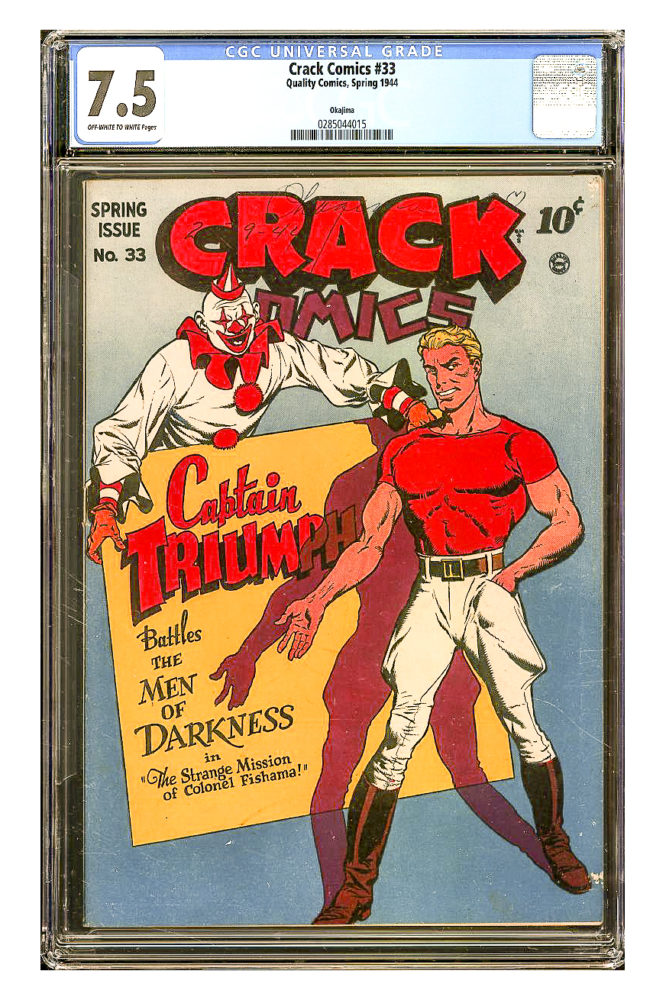

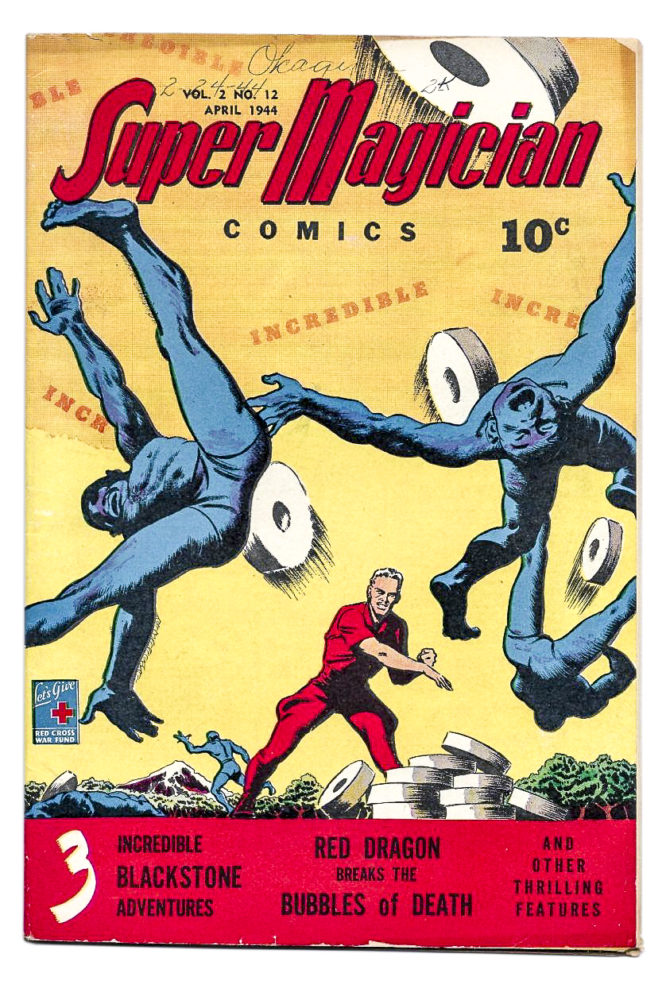

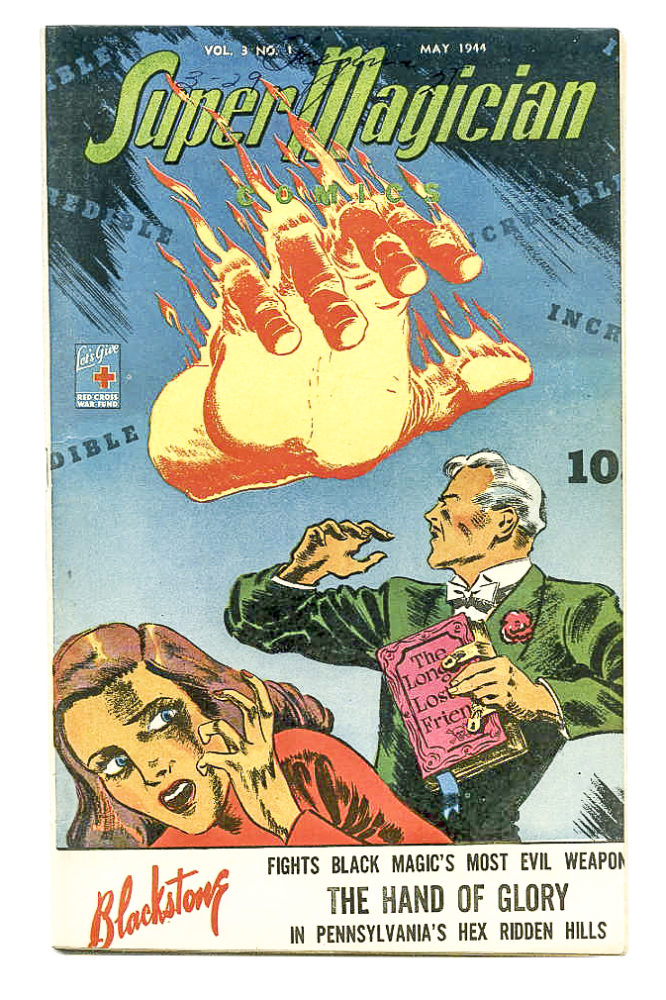

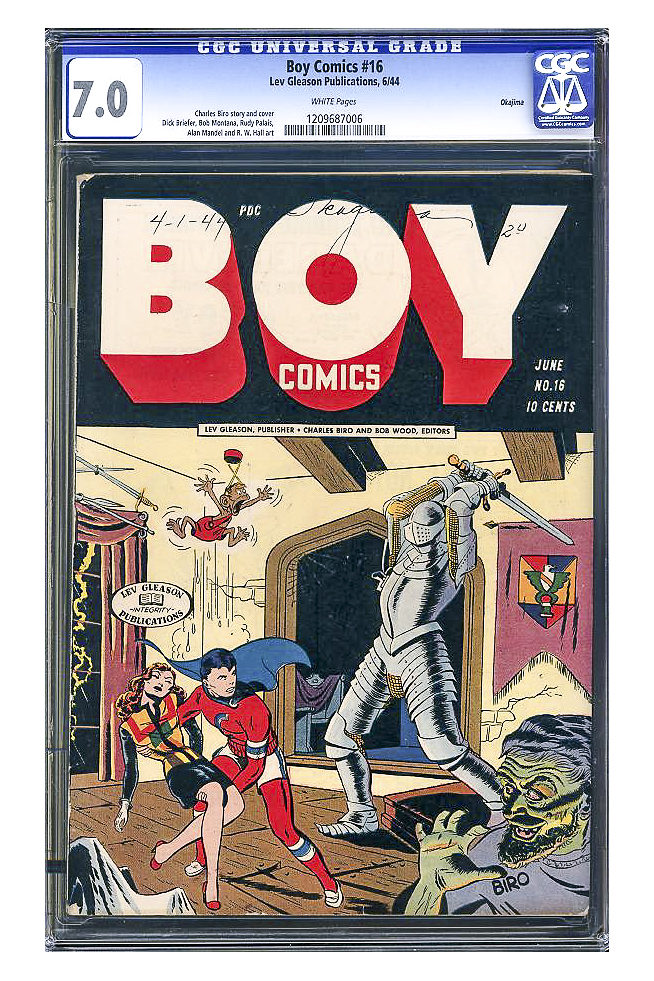

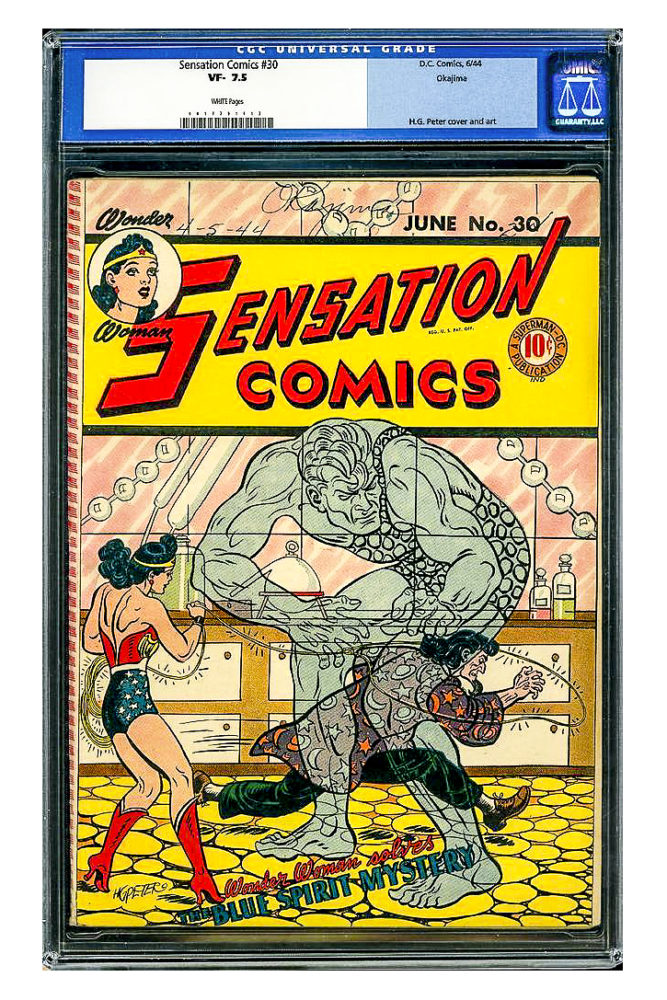

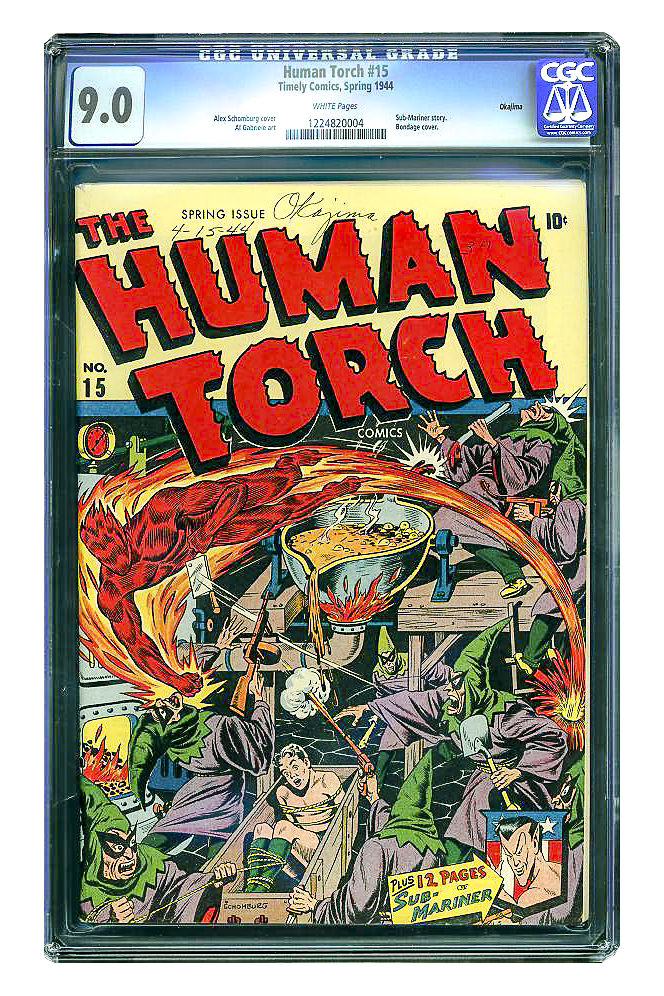

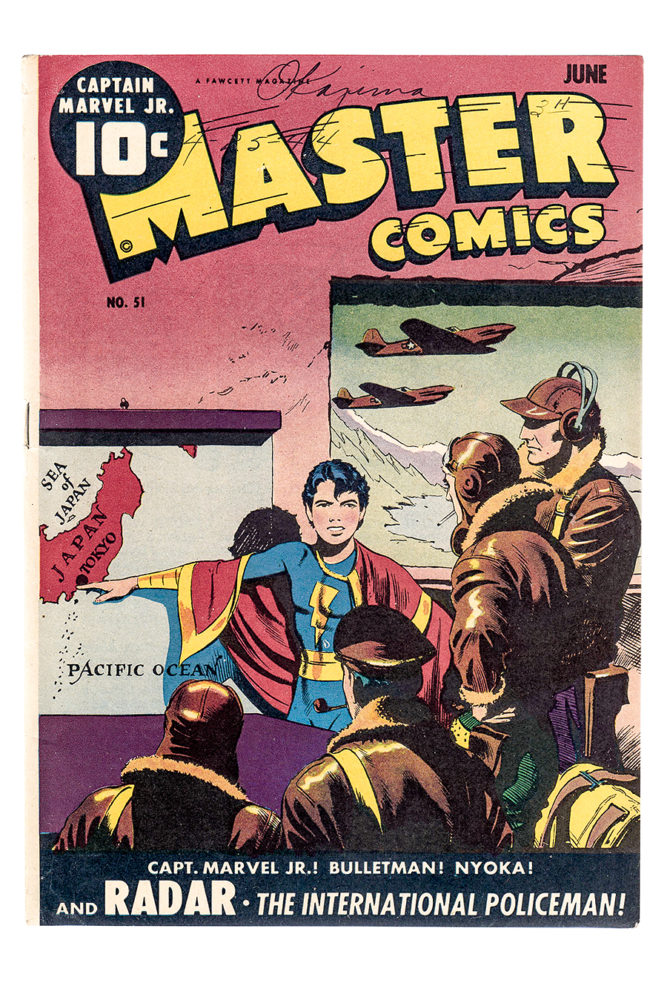

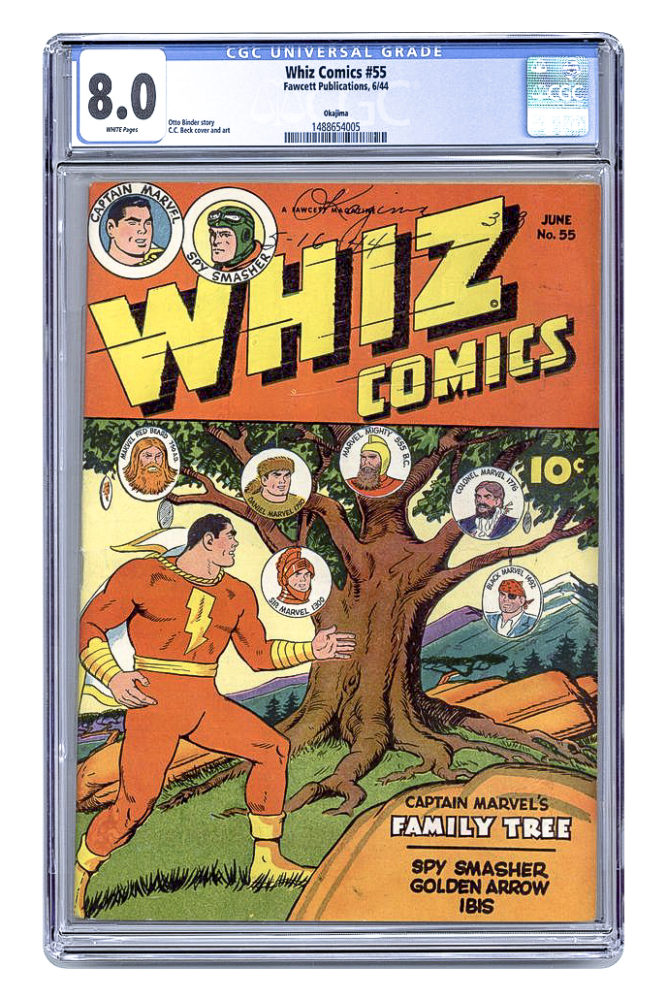

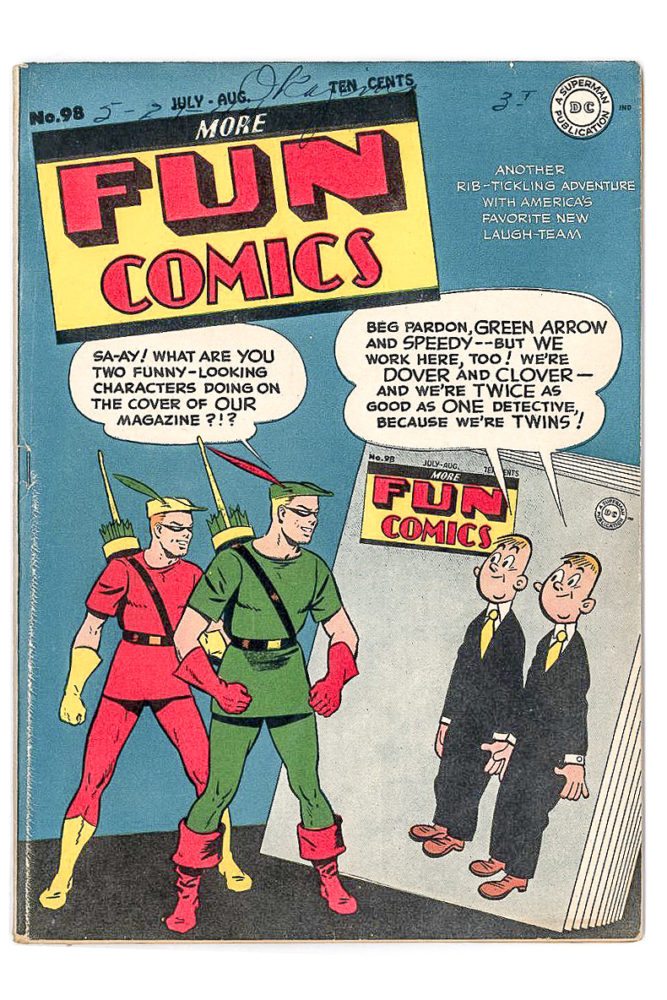

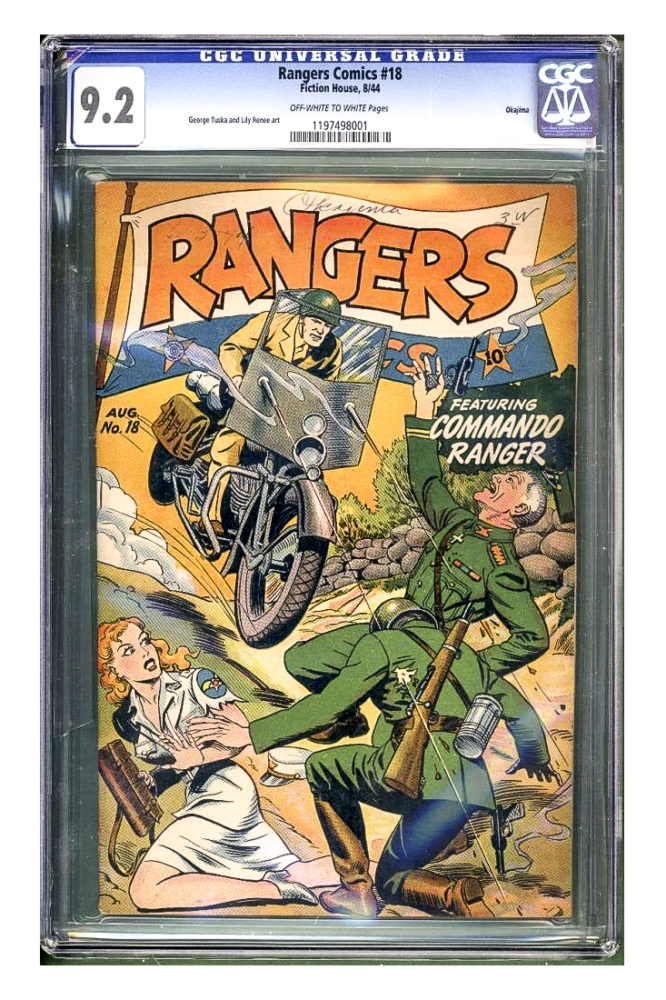

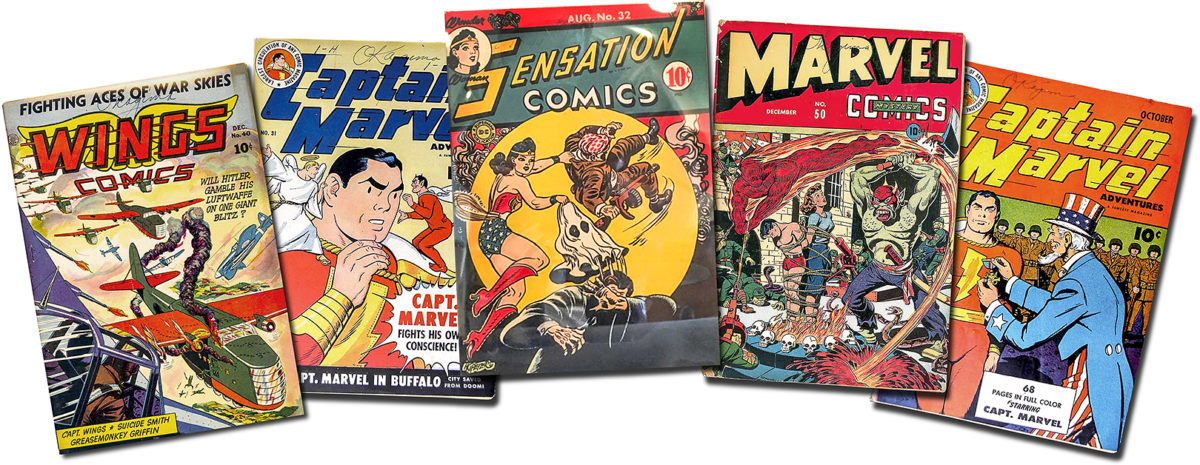

By the dim glow of a dangling light bulb in a barrack without running water, Bette devoured the Golden Age exploits of action heroes such as Captain Marvel and new titles like Wow and Startling. She liked “good girl” comics too, whose heroines “kicked butt,” said Matt Nelson, a comic industry expert.2

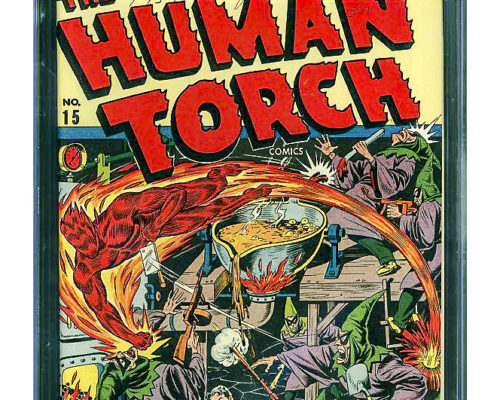

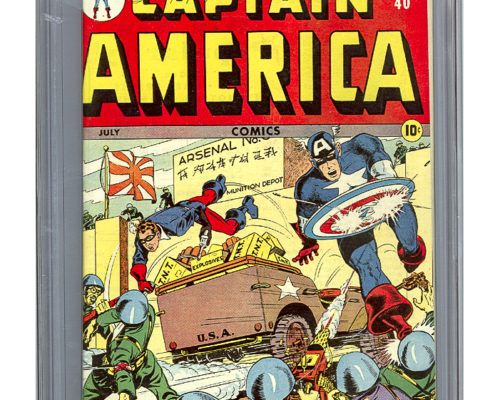

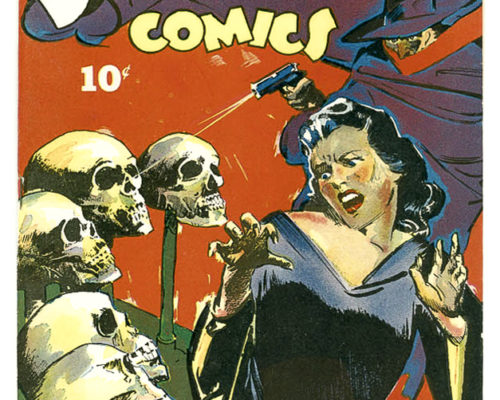

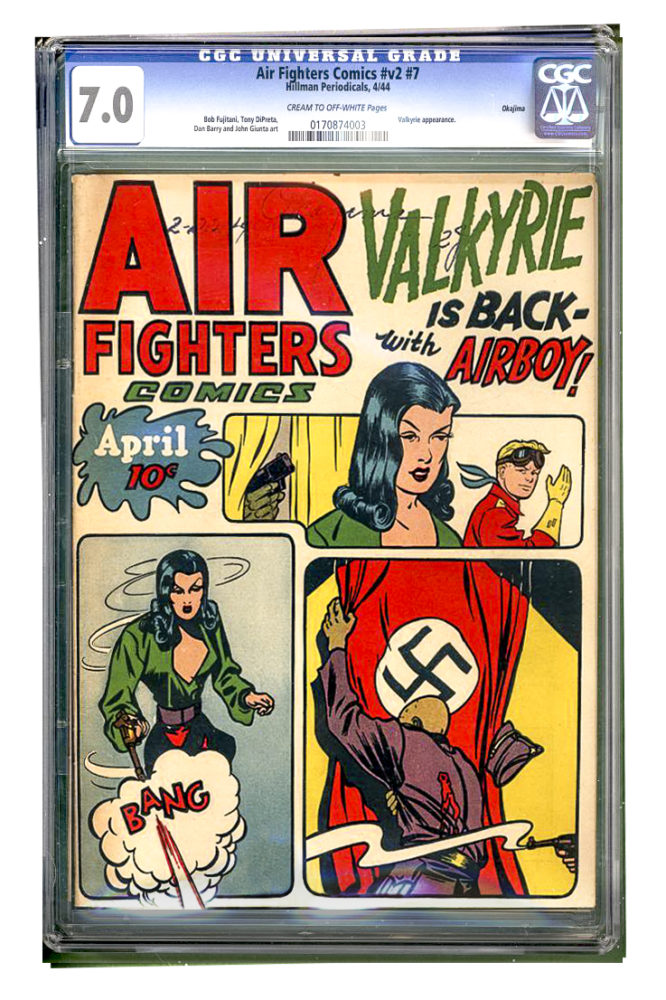

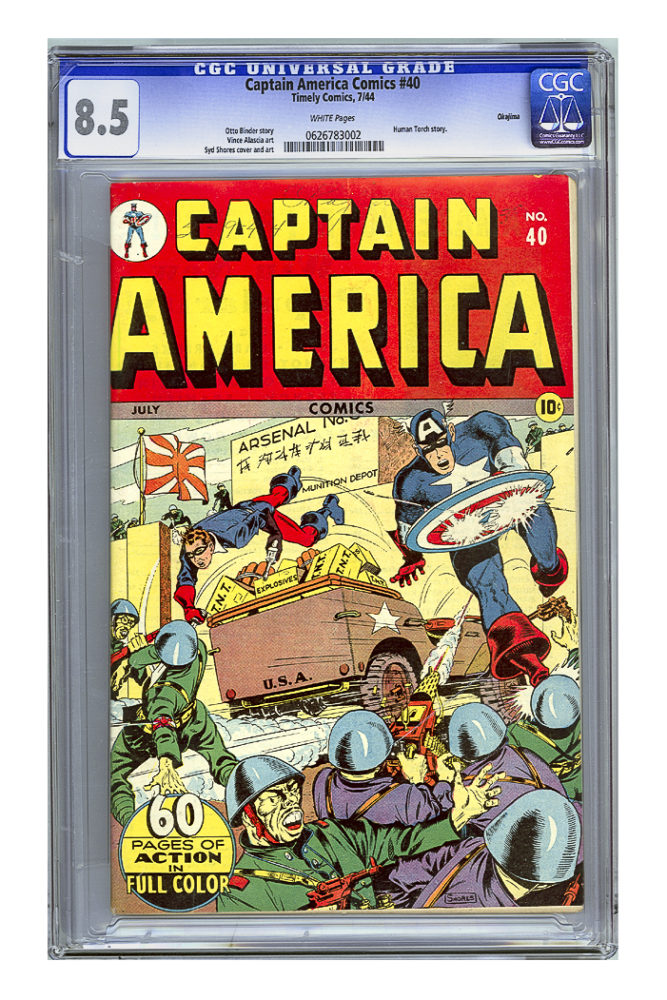

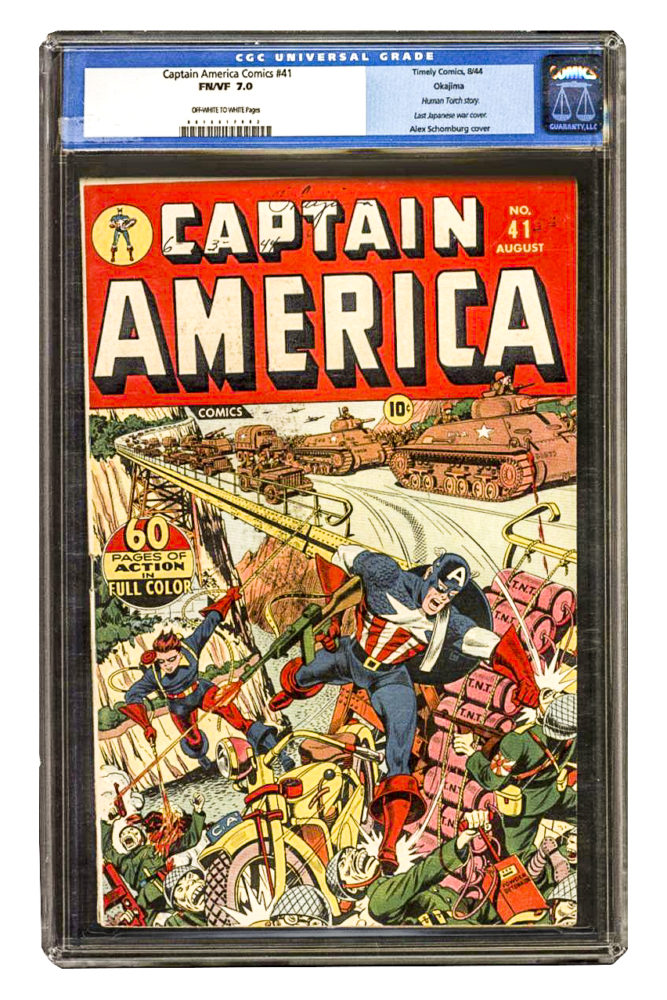

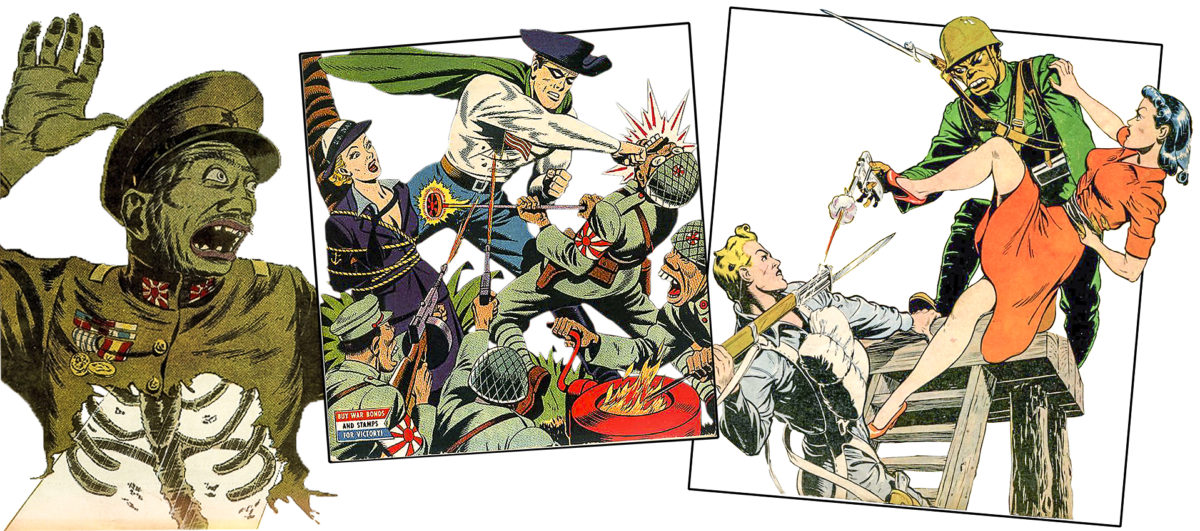

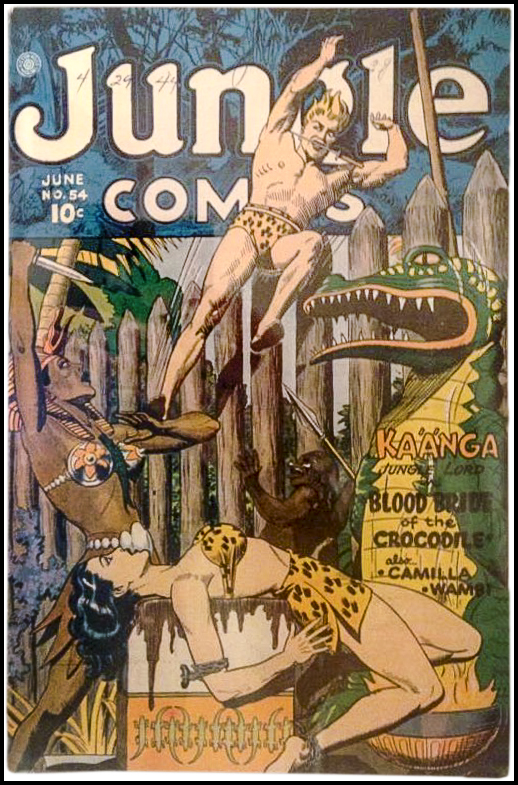

Many of the villains in Bette’s comics had the same Japanese face as she but with slanted eyes, buck teeth5 and mustard yellow skin.

Bette was a California-born U.S. citizen, but her nation was at war with Japan, and comic book artists, and even her own country, saw her as little different from the subhuman enemy depicted in dimestore escapades.

Comics in confinement

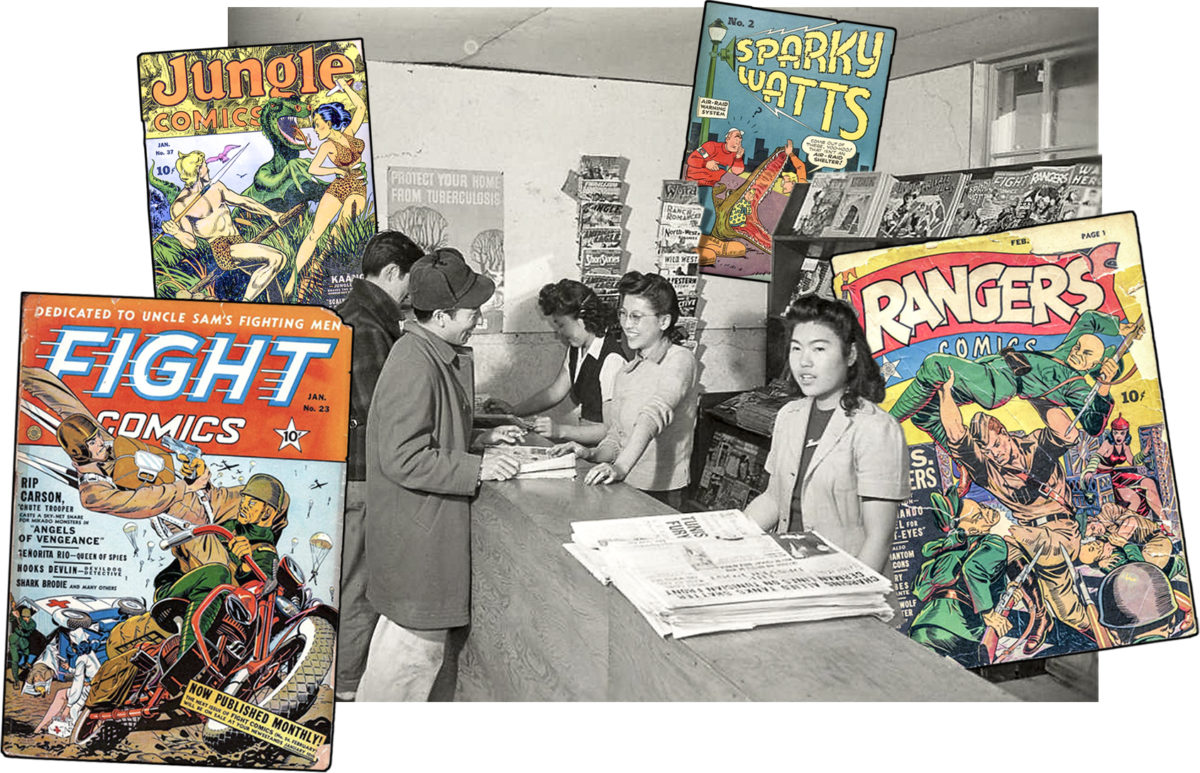

Comics were sold at the camp newsstand. Bette would have shopped there after entering the Gila River concentration camp in southern Arizona. She arrived on Aug. 8, 1942, with her widowed mother, Takano, and two younger siblings, Frances, 18, and George, 17. They were moved out of central California in a 500-person trainload, probably Bette’s first train ride, says Gerry Kataoka, a nephew. There were six trainloads out of Sanger in the Fresno area.6

The youngest Okajima, Hiroshi, who was disabled, had been left behind in an institution. The remaining family of four was assigned to Block 21 and occupied the middle, unpartitioned “C” space of barrack 13 in Canal Camp I, about three miles from a second camp at Gila River called Butte. Meanwhile, their home and 40-acre farm in Sanger were being “looked after” by the United Packing House Company.9

Two months after Bette completed the questionnaire, national security cleared her for indefinite leave with a condition: she “may not be employed in plants and facilities important to the war effort,” perhaps because she had studied Japanese in her youth. No matter. She had studied sewing at Sanger High School and intended to find work as a seamstress.

Bette was given $25, a train ticket and a parole card with her mugshot and fingerprint. On Oct. 17, 1943, she left George and her mother behind to reunite with Frances, who had gotten married in camp to Frank Kataoka and been released to Chicago.

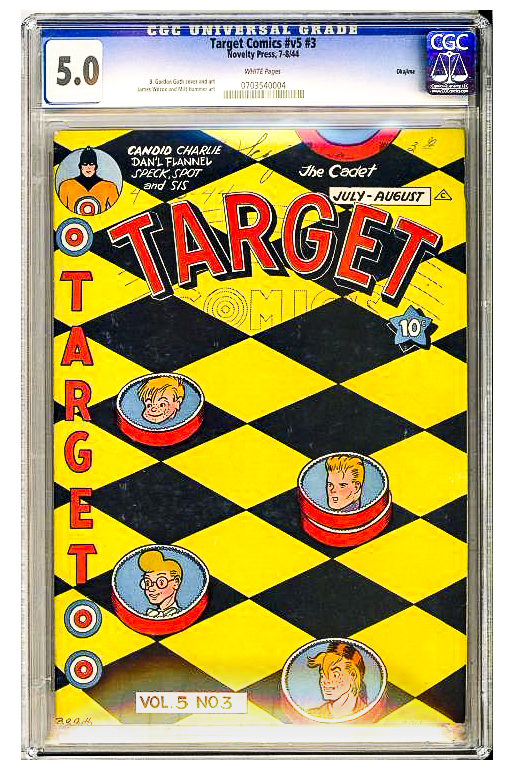

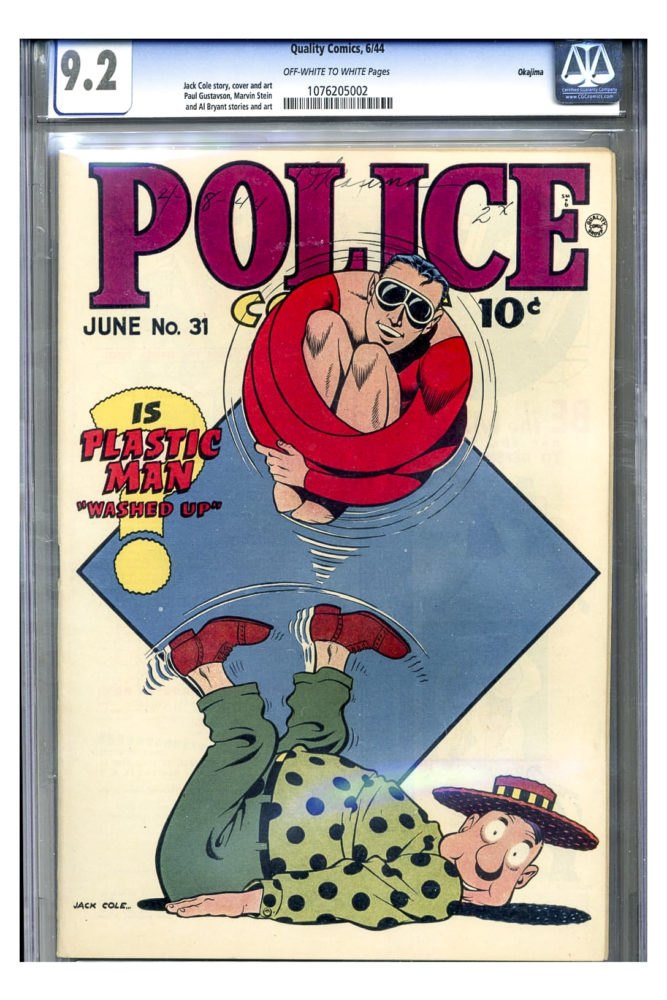

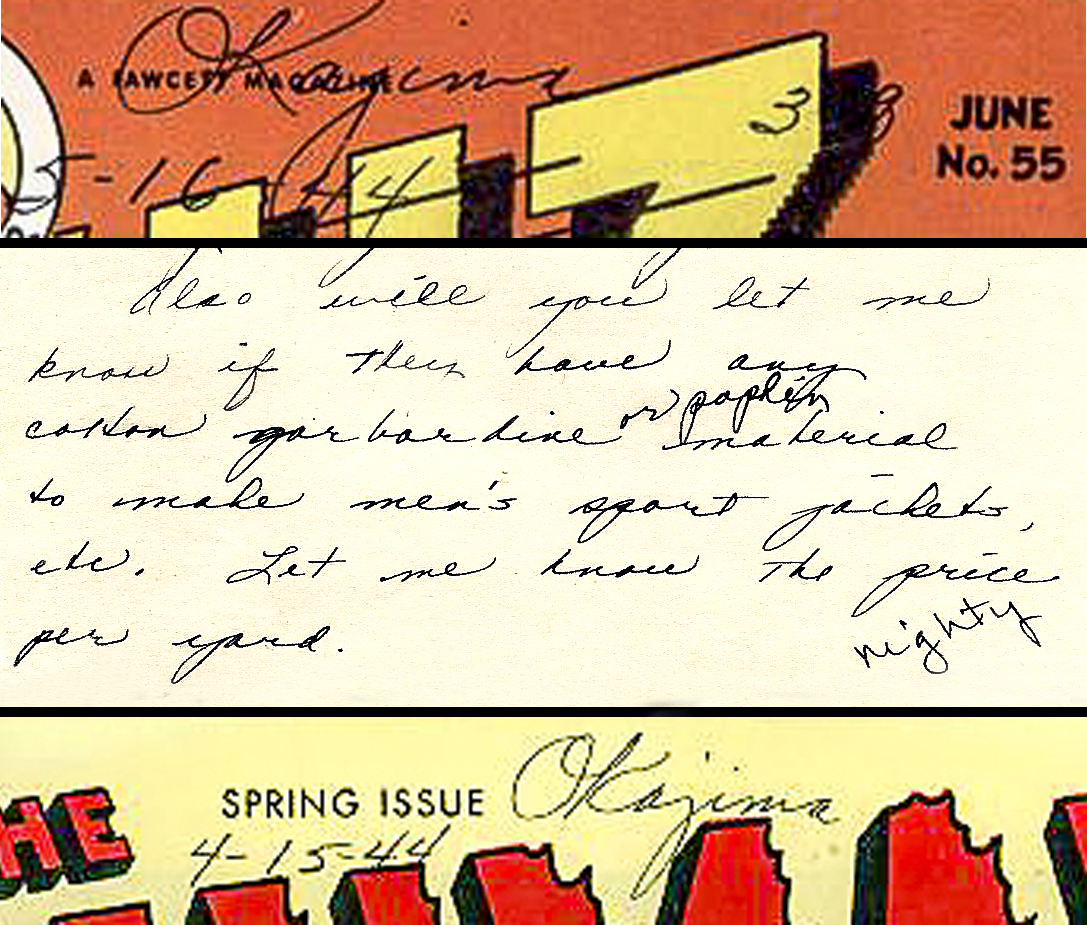

It isn’t known if Bette took the comics with her, left them behind or had them shipped later with her sewing machine. But it is believed that she bought comics in Chicago, sometimes writing her name, the date and a private code of letters and numbers on the covers.

After the war ended, Bette married Toshio Nakamura in 1946 and moved to Sacramento where the couple operated a hardware and furniture store in Japantown.

Bette’s in-laws ran “a pharmacy across the street,” Kataoka said. “And guess what the pharmacy had? They had comic books. So her collection continued” in the postwar period, Gerry believes.

Toshio died in 1956 of leukemia, leading Bette, 34, to return to Sanger with their two young sons. The comic collecting stopped.

Some 40 years later, Bette’s collection, thought to total more than 1,200 issues, was dispersed. How that happened is a mystery, even to surviving family members.

Comic community lore has it that in 1995, three dealers were rummaging through an Okajima estate sale in Sanger when they discovered three neatly-wrapped stacks of highly collectible Golden Age comics in a shed. They divided the spoils.

But the family asserts that selling their belongings to the public “is not something we would do,” Kataoka says.

Uncertain provenance notwithstanding, her comics began to trade in collector shows.

At first, the signatures were considered a flaw since collectors prefer clean covers.

But the Okajima comics grew in desirability as the unique back story became known: a female collector who, unjustly imprisoned by her own country, carefully preserved the earliest examples of action hero comics at a time when the medium was considered trash.

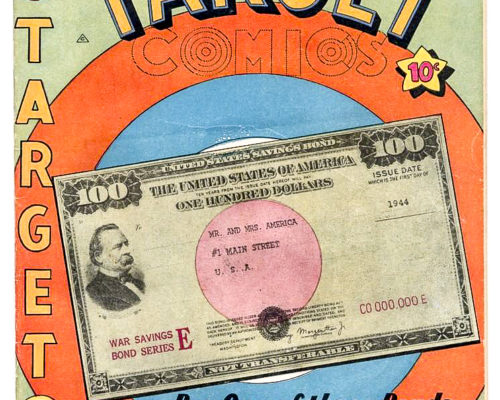

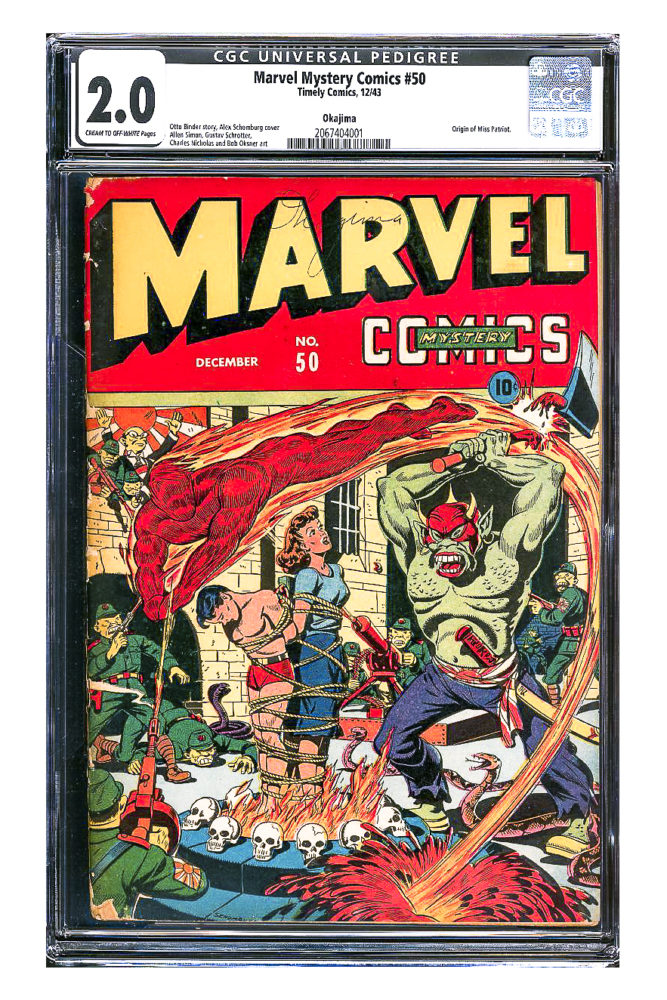

In 2000, the Okajima collection was elevated to “pedigree“ status by the CGC firm, which grades collectible issues and slabs them in plastic cases. Pedigree collections must be large in number, of high physical quality and acquired at the time of publication.

The Okajima Pedigree was one of only 12 such designations at the time and the only one awarded to an Asian American woman. The issues, many prized for their pristine pages, rose in value. Over time copies would come to sell for thousands of dollars each.

News of the pedigree enthralled the comic book world but collectors didn’t know that Bette was still alive, residing quietly in Sanger.

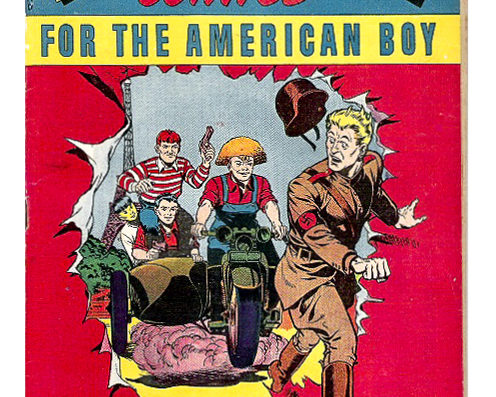

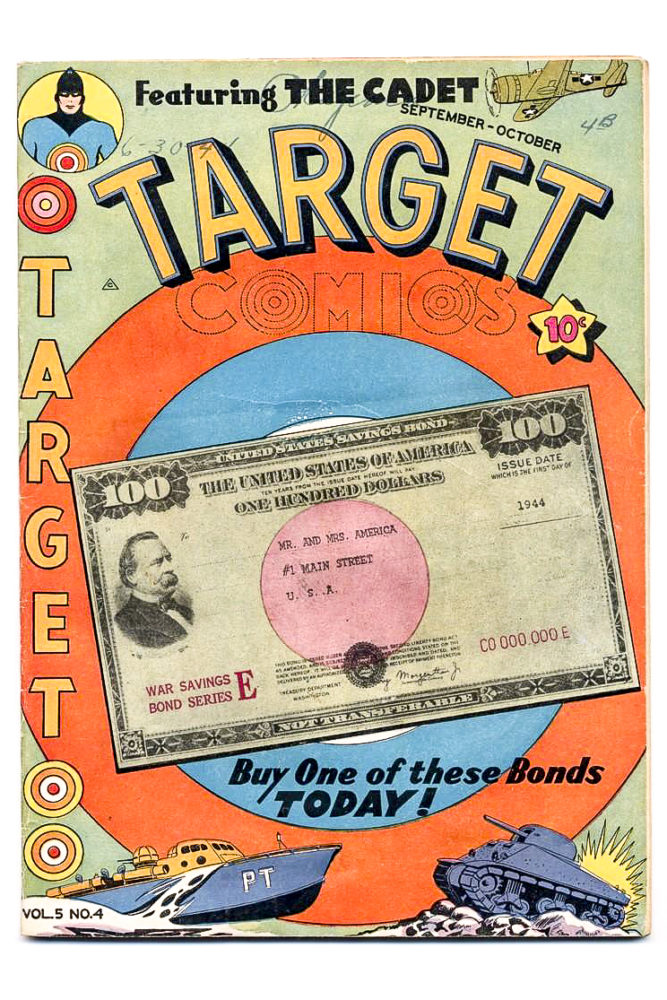

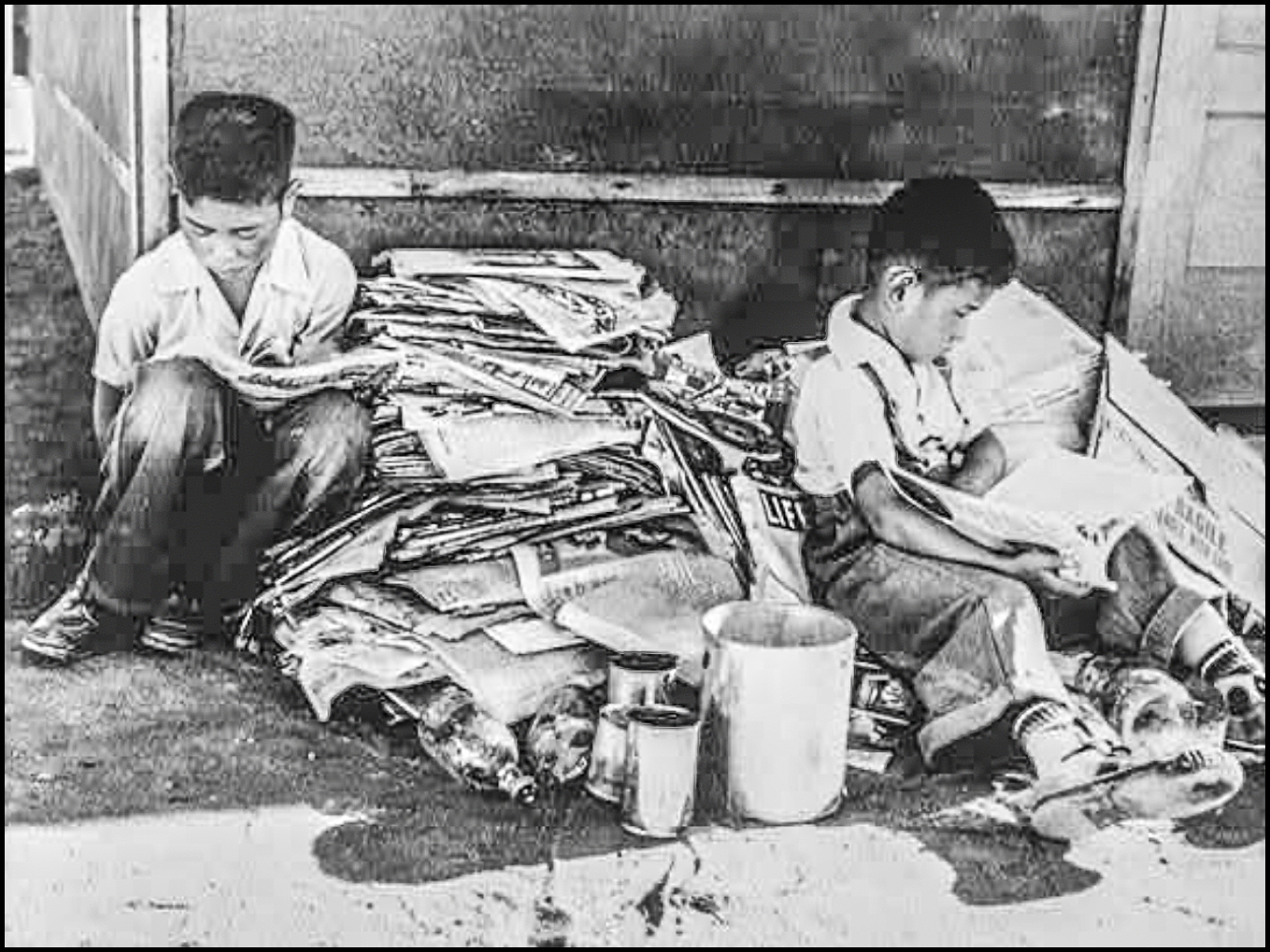

Comics were the most popular entertainment among U.S. children during the medium’s “Golden Age,” between 1938 and the early 1950s, which birthed Superman and the action hero archetype. Readership surveys show that more than 95 percent of elementary school-aged children read comic books and comic strips regularly.11 Cheap and shareable, comics were the video game of their day, only more accessible.

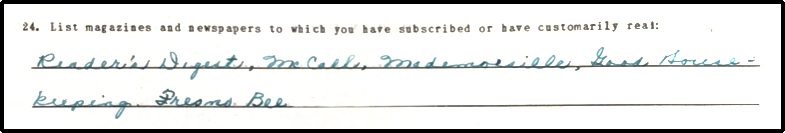

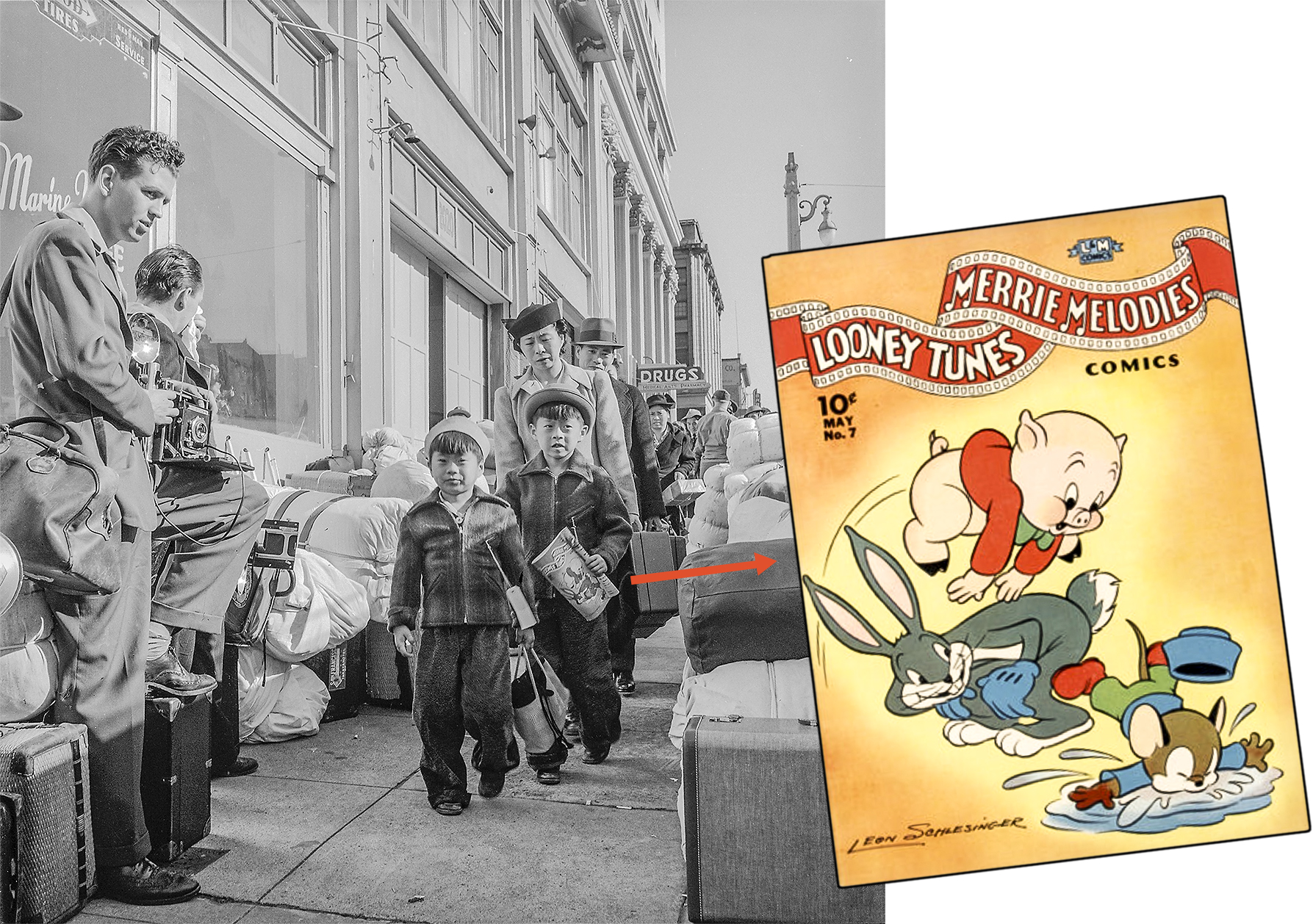

So it was not unusual that children escaped to comics during the trauma and upheaval that ripped their communities apart in 1942. Roosevelt’s presidential order emptied the West Coast of 110,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans within a matter of weeks in the spring. After the exclusion zone expanded in California to cover the entire state, roundups took place in the summer, too, as was the case with Bette.

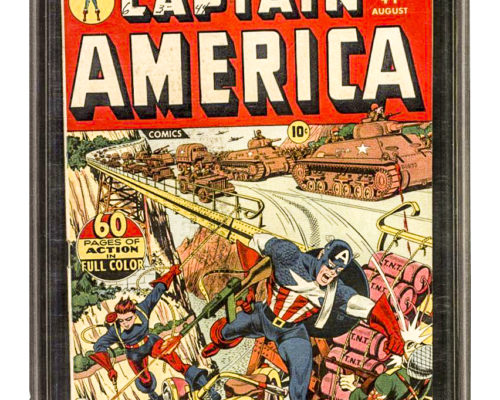

Government photographs taken during the mass removal show children immersed in the alternate reality of Looney Tunes and Captain America.

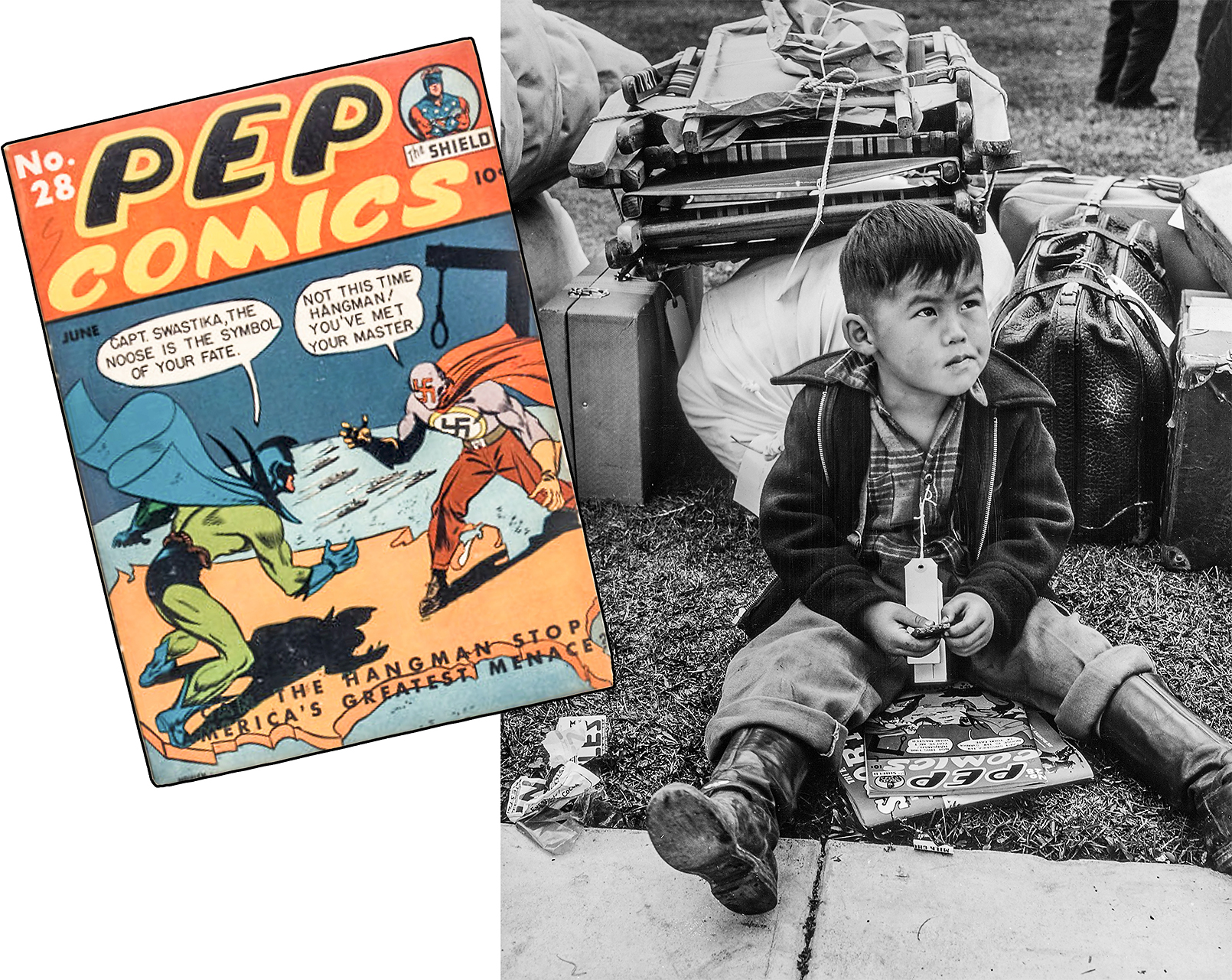

Inside the camps, comic culture flourished in barracks, at co-op newsstands and even in makeshift libraries. Among the first donations to the Tanforan library in San Bruno, California, were ten comic books.13

Robert Kono, born in Los Angeles, read comics as a 10-year-old prisoner at Crystal City, Texas, before his family was deported to Japan. On the night of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the FBI took his father away. The family was separated for two-and-a-half years, during which time Robert was cycled through four camps. “I bought (comics) at the canteen” in Texas, he said. “Captain Marvel, Tom Mix, Superman” and a memorable issue about Robert Louis Stevenson. “My early education was in comics.”14

Mas Hashimoto, of Watsonville, California, recalls reading them while he was a patient at the Poston, Arizona, camp hospital. He disinfected the issues afterward by exposing the pages to the sun and turning them, one by one, every few minutes, he said. His friend, Ed Hirose, “lent them out for three cents a read.”

Arthur Yamada said that when he was ten years old at Manzanar in eastern California, “comics saved my life.” When he was forced to stand in front of class and make a report, he was stymied.

“I had to, at that young age, come up with something to say or a story to tell every week. My reference material became comic books. I would take a comic book and read a comic strip, and then with the six or eight frames I would have to make a story up … So, kind of, comic books saved my life, to be able to get up in front of the class and tell stories.”17

A collector in San Francisco, Jeff Tom, sympathized with the imprisoned children and began a deep dive into the WWII history of Japanese American incarceration and comics, posting a comprehensive photo essay on a collectors board.19

“The Tule Lake newsstand was remodeled and enlarged in January 1943,” he wrote, “with 100 different comic titles added, from Action to Zip.”

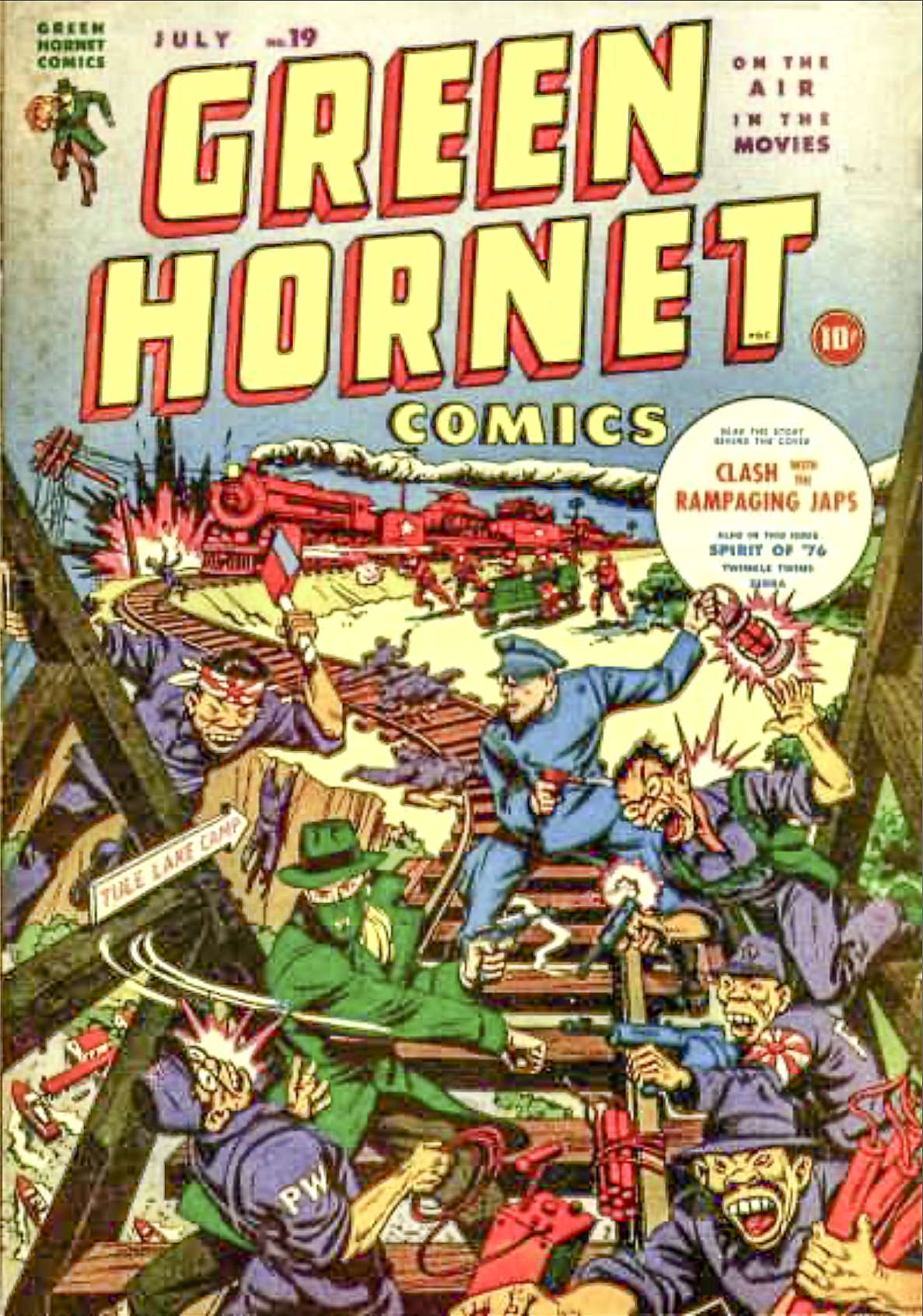

Propaganda within propaganda

Tom’s expert knowledge of the stories within each 64-page issue made him keenly aware that the children who were shown with comics in government propaganda photos were themselves reading propaganda that demonized their race. “Almost all the wartime comics have anti-Japanese stories,” he said.

He points to a War Relocation Authority photograph of four boys at a Tule Lake camp newsstand that shows a child grinning as he reads Marvel Mystery No. 34, which contains the stories, “Exposed! The Jap Invaders” and “Dr. Watson Makes Monkeys Out of the Japs.”

Beginning in April, 1943, during the period in which Bette would have been collecting, the Writers’ War Board, a quasi-governmental entity, worked with comic publishers to build support for the war. It “promoted race-based hatred of America’s enemies,” through comics’ powerful graphics.21

Building on old racial tropes, ugly caricatures visually conflated the Japanese enemy and U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry and their immigrant parents.

Images of vermin, apes, “primitive, childish, moronic” subhumans on the one hand, and super villains capable of the most brutal behavior on the other, were the extreme and uncensored visual language of wartime comics.23

At least the German enemy had the option of being “good Germans,” a privilege not afforded to Japanese.

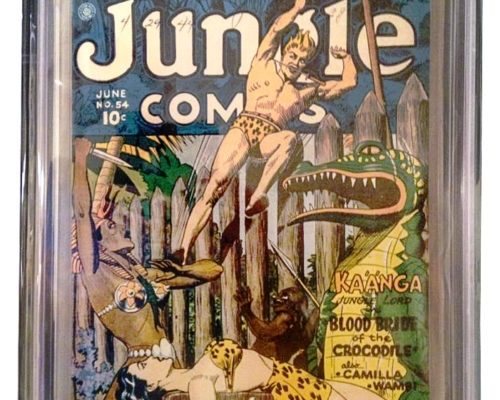

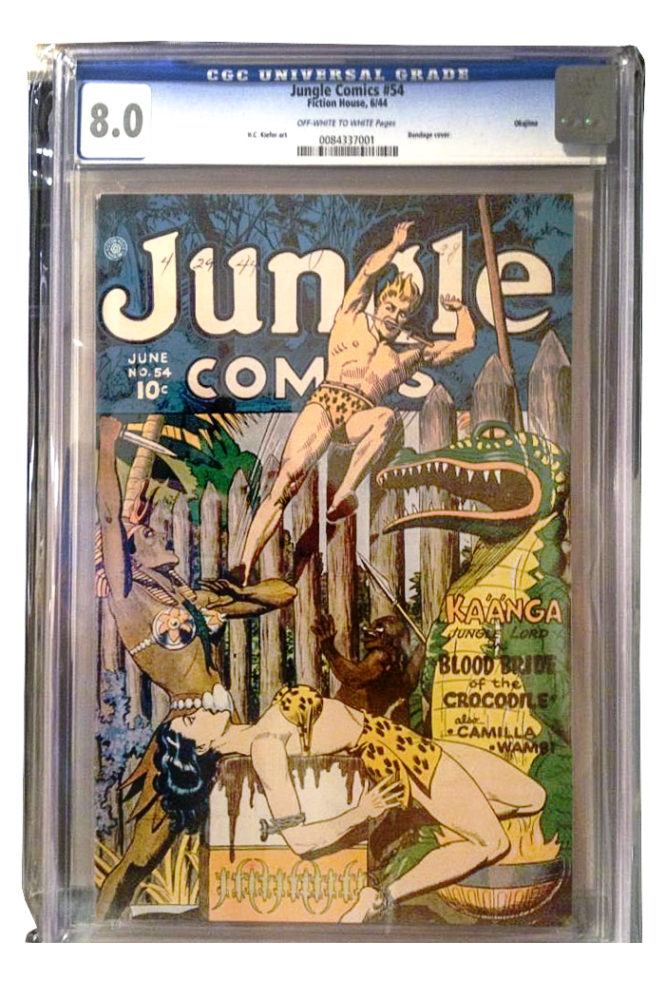

“They are racially pointed. You have to wonder, what was she thinking when she was reading them,” said Collin Dey of Anchorage, Alaska, who bought an Okajima book in the 1990s. Bette’s moving story connected him to the traumatic wartime experiences of his uncle, Robert Kono. Okajima’s Jungle No. 54, 1944, was his favorite, he said, out of a personal collection that at one point numbered more than 30,000.

Missing: girls and adults

The government’s photographic record noticeably leaves out girls and adults, large segments of the comic-reading population. In some surveys, girls account for half of child readers.

Boys are often shown with comics at newsstands or reading outdoors. One image shows boys sitting next to a trash heap where used comics might have been tossed.

This leads one to wonder if girls were reading in private spaces, out of reach of photographers, selectively excluded from the record, or enjoying their hobby in less visible ways?

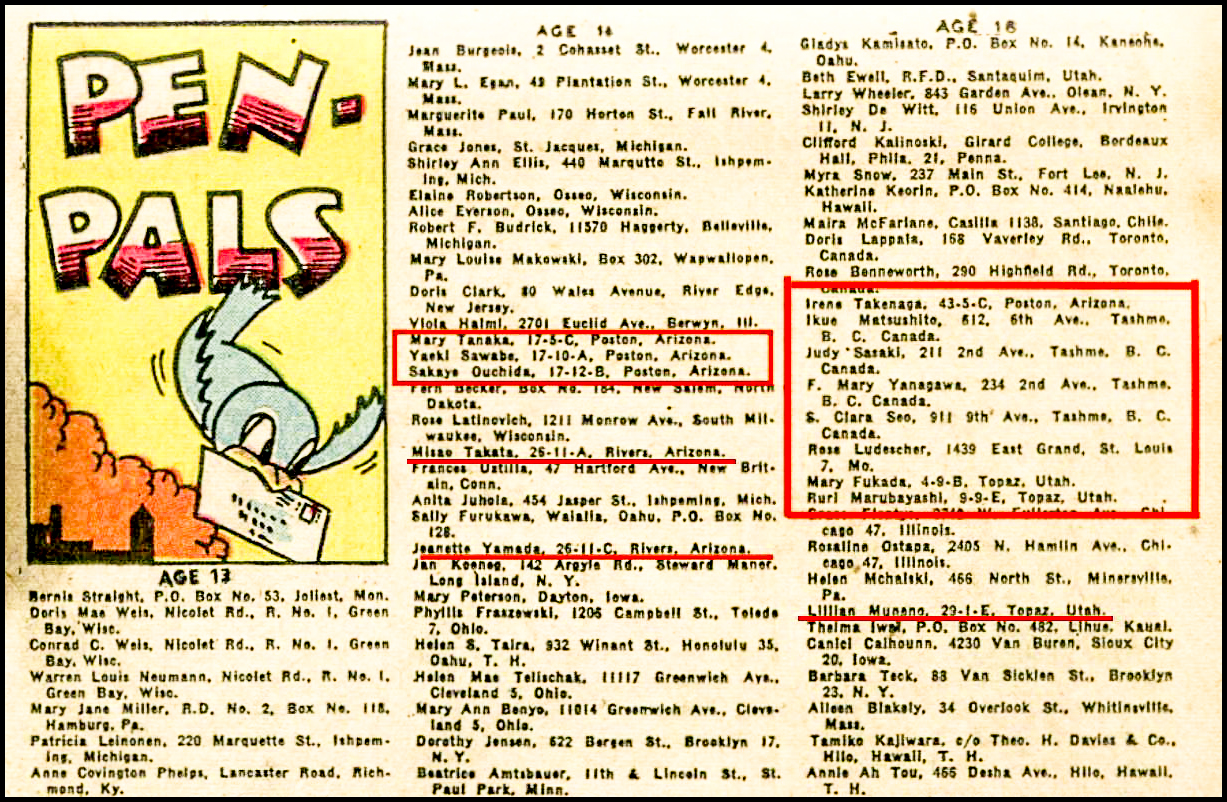

A look at the back pages of comics suggests that girls were actively engaged, but in a more gendered way, such as in pen pal clubs.

The back pages of Famous Funnies published names of pen pal seekers, grouped by age, who wanted to make a friend through letter writing.

“The cool thing is that a lot of kids were doing more than just ‘reading’ comics. They were using comics as ways of building social networks,” said Carol Tilley, comics historian, librarian educator and professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.25

A database of 31 “Pen-Pals” pages in Famous Funnies (issues No. 104, Feb. 16, 1943 — No. 150, Dec. 13, 1946) with at least one Japanese surname was created by Tom. It shows that imprisoned Japanese American girls – but very few boys – were busily seeking friends outside the barbed wire.

“Teachers were always trying to get us to do things like” write to magazines, recalls Chizu Omori, 92, who entered Poston, Arizona, at age 12.

Poston girls answered the call. An analysis of the Famous Funnies pen-pal database shows that of 79 girls incarcerated across the country who were seeking correspondents, 34 were from Poston.27

Girls seeking pen pals from nine of the 10 WRA camps were tabulated as follows:

Arizona: Gila River (8), Poston (34)

Arkansas: Jerome (0), Rohwer (2)

California: Manzanar (6), Tule Lake (9)

Colorado: Amache (4)

Idaho: Minidoka (2)

Utah: Topaz (6)

Wyoming: Heart Mountain (8)

The girls gave their barrack addresses as their domicile. Only four Japanese American boys’ names were identified, from Gila River (2), Heart Mountain (1) and Poston (1).

Nine Canadian Japanese girls – and no boys – also sought pen pals from the Tashme concentration camp in British Columbia via Famous Funnies. An attempt by this project to contact survivors to see if they were successful in finding a correspondent hasn’t yet yielded results. This would be interesting to know; an article about wartime pen pals stated that one popular pen pal seeker in the U.K. received 500 letters.

Outside the camps, in the “free zone,” where mainland Japanese Americans were not put into camps, three American Japanese girls and one boy, from Utah, Colorado and Pennsylvania, sought pen pals.

Few images of adult readers

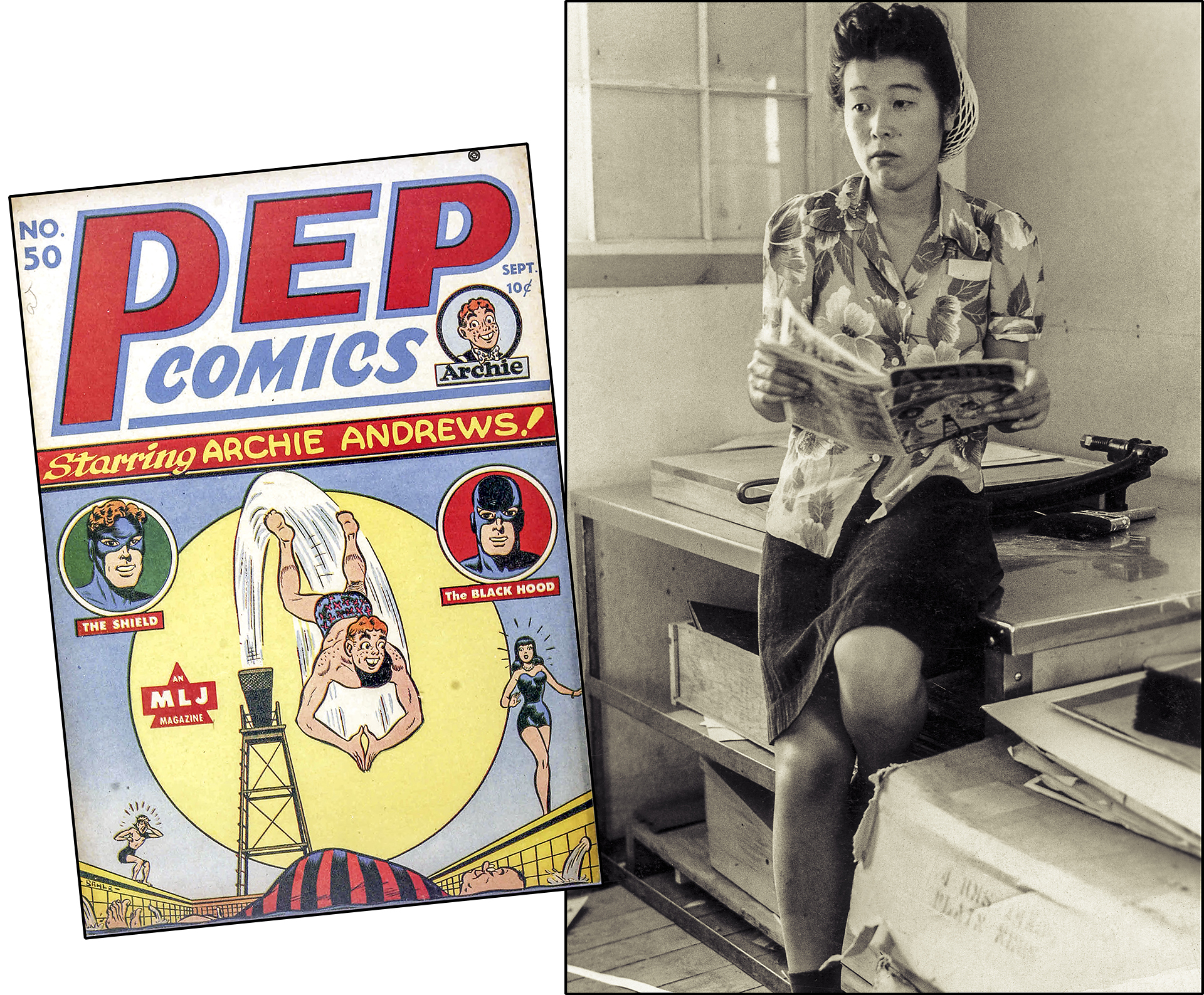

Only two images of adults reading comics have been located in the photographic record. Both were made by Japanese American inmate photographers.

George Ochikubo of Portland, Oregon, photographed an unidentified woman at Amache, Colorado. She is perched on a work table in a silk screen office, holding an issue of Pep, the first media home of soda counter denizen Archie Andrews.

A second photo shows young adult picnickers at Manzanar taken by portrait photographer Toyo Miyatake of Los Angeles. Couples are laughing and relaxing at Bair’s Creek, in the southwest corner of the camp, with Superman No. 30.

There is no known photo of Bette during her incarceration at Gila River, with or without a comic.

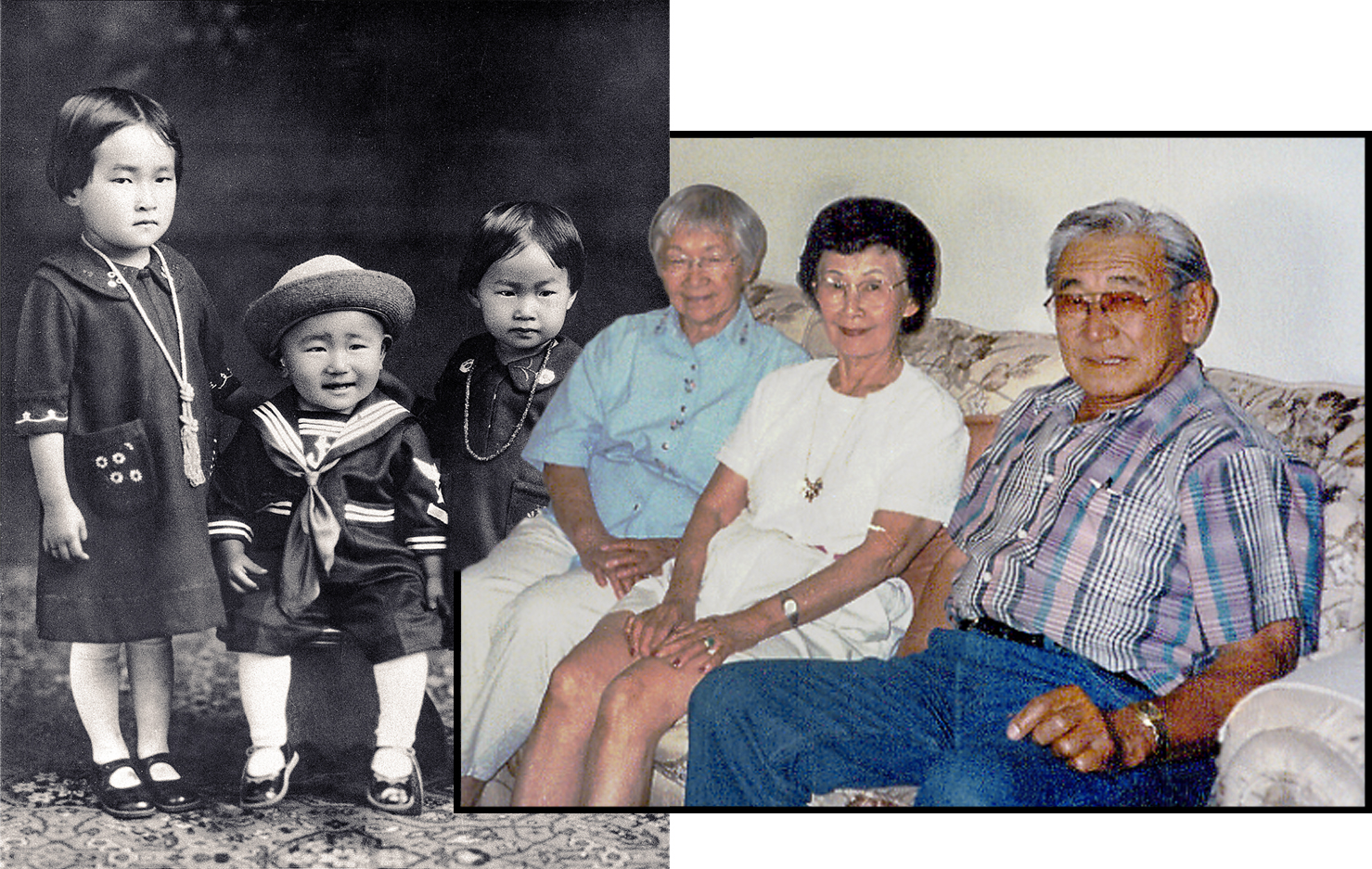

Fumiko Bette Okajima was born on Nov. 24, 1921, at the Eda Maternity Home in Fresno, California, a year after her mother, Takano Kawai, emigrated to the U.S. from Okayama at age 16, with her new husband, Masuo Okajima. Bette was the eldest of Takano and Masuo’s four children.

Masuo died at age 39 in 1936, when Bette was 15. He left a rare legacy: 40 acres of farmland that his father had acquired in the early 1900s before the Alien Land Law of 1913 banned Asian immigrants from buying property. Land ownership was so rare that at Gila River, Takano said she was known as the “rich widow who cleaned toilets in Block 21,” a job she took to escape mess hall gossip.29

Before the war, Bette helped tie the vines and harvest Thompson grapes, figs and oranges. She and Frances also “had chores around the farm, like feeding chickens,” Gerry, the son of Frances Okajima Kataoka, said. “They had their choice: stop working on the farm early and start the fire for the bath, or start dinner and feed the animals.”

Bette attended Japanese school, studied Spanish at Sanger High School and played tennis and the piano. In camp forms, she described herself as trilingual in English, Japanese and Spanish; able to type 50 words a minute; and listed typist, seamstress and sales clerk as her preferred jobs.

Camp records show that she lasted one week as a mess hall wait staff before quitting to become a sales clerk and then moving up to co-op cashier – possibly moving her closer to the newsstand? – for $16.00 a week. She was promoted to Girls Department head with a $3.00 raise before gaining her freedom after 14 months of imprisonment.

Losses colored her life. The deaths of her father in 1936, her youngest brother in 1948 and husband in 1956 may have drawn her closer to surviving family members. She never remarried and worked at Gong’s Market while living with her mother in Sanger. They raised the two boys in a small house that was built 150 yards away from the original family home.

Bette cared for Takano, who became bedridden, for 20 years until her death. Bette and Frances subsequently moved in together in nearby Selma and the sisters attended exercise class, bingo and the movies, Kataoka said.

No one in the family was aware of Bette’s collection until a stranger called to inquire if they were connected to the Okajima pedigree. Kataoka asked a friend’s nephew to look into the claim and the answer returned, “Yes, the pedigree is well known.”

But by then, the collection had been dispersed and Bette was suffering from memory loss. When Kataoka interviewed Bette for his memoirs, he said, “I had some questions about what they did when they got released from Gila and she’d just say, ‘I don’t know, I don’t know.’”

“There was a lot of trauma in that early period of her life and I think the comic books are part of it,” he said.

The handwriting on the comic covers matches that on the cards and letters Kataoka received from his Aunt Bette from childhood. The meticulous preservation of the collection is characteristic of her orderly habits. “The way she catalogued it is part of her personality. She kept an immaculate house, even though she worked a job as a single mom and raised two boys” — who happened to be avid comic readers. “They always had the latest comic books. We didn’t, we couldn’t afford them.”

An examination of the National Archives Japanese American Internee Data File, 1942-1946, turned up six people in three families with the Okajima surname out of 109,377 records. Bette’s family accounted for three of the six Okajima listings.31 Two other Okajimas were from Oregon, imprisoned in Idaho. A sixth Okajima was born in Japan in 1885 and incarcerated at Poston.

In 1995, about 400 Okajima comics were purchased by a California collector, reportedly from a Central Valley source. In addition, high-grade Okajimas were said to be surfacing in the Central Valley along Highway 5 between Sacramento and Bakersfield.

While examining his Okajima inventory, the collector discovered versions of a letter tucked into the pages of a 1944 comic in which the writer asks about the price of fabric. Bette was in Chicago with her sewing machine at this time, so assuming the cursive is hers, she is ordering cotton gabardine to make men’s sports jackets.

As a result of the apparently unsystematic dispersal of the collection, and doubt cast on the estate sale story by family members, an accurate total may never be known. Unsigned Okajimas were likely purchased at comic shows and even if they bore her distinctive markings, an uninformed owner might not recognize them.

No Okajima sells for less than $1,000 now, unless it is low grade. The most admired Okajima issues are said to be the classics, Sub-Mariner No. 32 and Startling No. 49, which are in excellent physical condition. Together they could sell in excess of $100,000, according to a veteran dealer.

When asked about the mysterious circumstances of the collection’s dispersal, Kataoka speculates that a family member may have sold the collection but adds that those who would know are no longer alive.

On June 30, 2021, Bette passed away at age 99, after suffering a stroke. She was the last survivor of the family, having outlived her sons and siblings. Kataoka had hoped to celebrate her 100th birthday with a celebration of her World War II pedigree collection and its story.

Instead, he spoke at her grave site at the Sanger cemetery about her collecting passion, sharing details which some family members were hearing for the first time.

Kataoka related memories of his Aunt Bette and his mother. They shared life in a barrack cell at Gila River and never spoke of it again — except for passing mentions of the heat, dust and “fun” times. For Bette, comics must have helped temper the tedium, soften the hardship and provide a temporary mental escape, he said.

Artifacts of war and loss

The question of how an important collection could languish in a home for decades puzzles some. “When somebody has something that they don’t look at for 50 years, do they remember that they have it? Does it matter to them?” a collector wonders.

Bette’s comics, however, may fall into the fraught category of camp and post-camp artifact: too important to discard, too sad to unpack. Camp remnants and their entangled memories have been buried for decades in Japanese American attics, closets, basements and garages.

Unlike Golden Age comic stories, there is no triumphant closure or clarity on the Okajima books. For a purist, “the overall quality of the books, the fact that they survived in such wonderful shape despite the odds” should be appreciated, said a dealer. “But by its very nature, the story is integral to how people feel about the collection. The two can’t be separated.”

Questions about race, gender and social justice are now laced into the pages of Bette’s books. She defied gender expectations by not buying romance or Disney. The comics ask how American Japanese read the racist messaging in the art and storylines.

For Tom, Bette’s books spark dialogue on injustice. When an Internet commenter blithely wished that they could have been at a WRA camp to buy the classic comics, Tom wrote a long photo essay for the comic community to deepen their historical knowledge.

Another online contributor expressed empathy. He replied to the author of an essay on Bette: “I think about this collector often. I think about when her family was told they had to pack a suitcase to leave … I love the fact that during this very difficult time she collected (and signed) each book so she could always claim ownership of them. Did she hide them? … And the fact that once she and her family were free and relocated that she kept collecting. These are the things I dwell on as I look at these books. It’s an amazing story and the pedigree gives us a partial glimpse at one woman’s love of comics during a dark part of America’s history. Thanks for posting it.”

Credits

June 3, 2022

by Nancy Ukai

art direction and digital illustrations: David Izu

Cover Images:

Comic book covers — Captain America No. 40 courtesy of Richard Evans, Master Comics No. 51 courtesy of Ron Hobbs, Air Fighters Volume 2 No. 7 courtesy of Colin Dey, Sensation Comics No. 30 courtesy anonymous, Red Dragon Comics Volume 1 No. 7.

Okajima family photos courtesy of Gerry Kataoka. Gila River landscape courtesy of CSU Dominguez Hills Department of Archives and Special Collections.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Jeff Tom

Gerry Kataoka, Robert Hiroshi Kono, Collin Dey, Mas Hashimoto, Gary Ono, Matt Nelson, CGC Comics, Alisa Lynch, Sarah Bone, Manzanar National Historic Site, Alan Miyatake, Densho.

Supported in part by The National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program

Disclaimer of liability

The material contained on this website is for information purposes only. Using this information as a basis for business or investment purposes is done at one’s own risk.

© 2022 50 Objects/Stories