Nakamura family gatherings have routinely brought together four generations of relatives, most living within a 20-mile radius of San Jose, California. The elders, if asked, will talk about how they escaped the West Coast before the government began to round up Japanese Americans in 1942. But memories fade. Elders have passed away.

No one knew that records of the family’s wartime history lay buried in a government file in the National Archives, in Washington, D.C. Each of the 109,384 Evacuee Case Files, compiled by the War Relocation Authority, is a memorial to the hardships of the concentration camp years. The Nakamura file was particularly so.

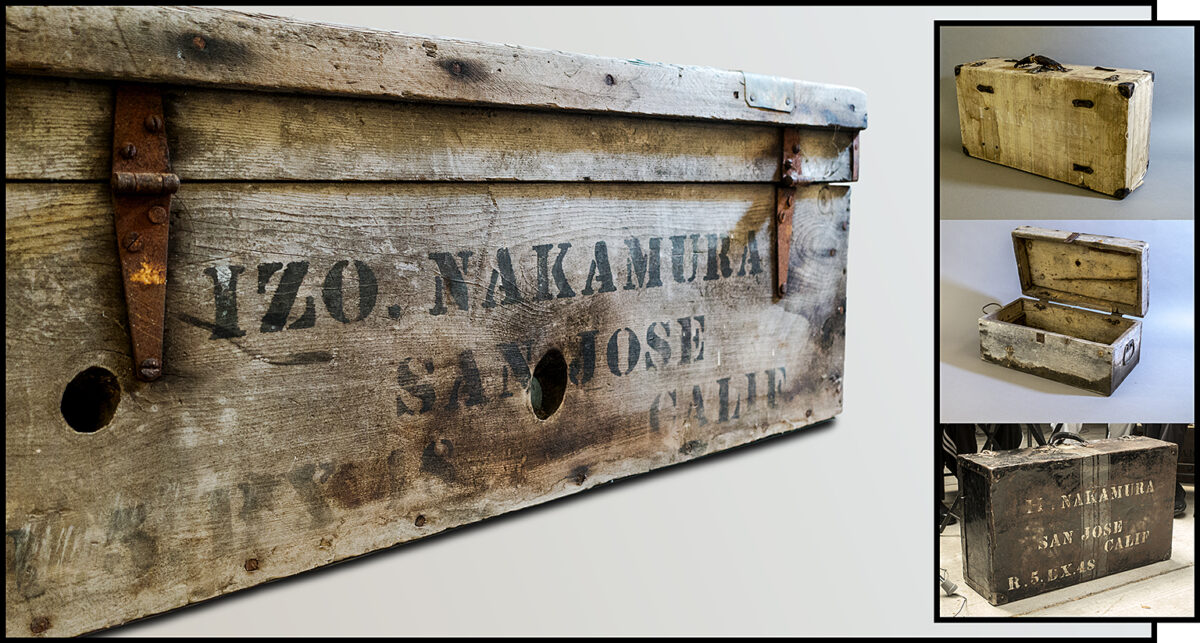

With the permission of the family, the 50 Objects project pulled the file of Izo Nakamura, the immigrant head of the family. Out came letters and government memos which showed how he struggled for seven months to get the family of nine into a camp.

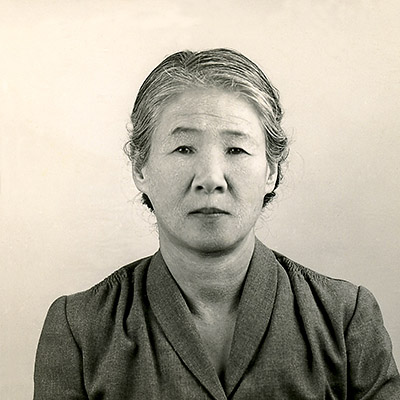

Izo Nakamura was born in 1887 in Wakayama Prefecture. He arrived in the U.S. in 1903 and over time became the leader of a cluster of 30 Japanese immigrant families living on Trimble Road in San Jose. Izo became known as “the celery king.” He built a thriving business on leased land with his wife Some (pronounced so-meh), a picture bride from Wakayama, and their children, who worked in the fields after school. The children remember the plow horse but the pleasure of treats, too: music lessons, Saturday matinees, waiting for the fish and tofu peddler. “We could go to the department store and buy clothes,” Bettie, the oldest daughter, recalled.

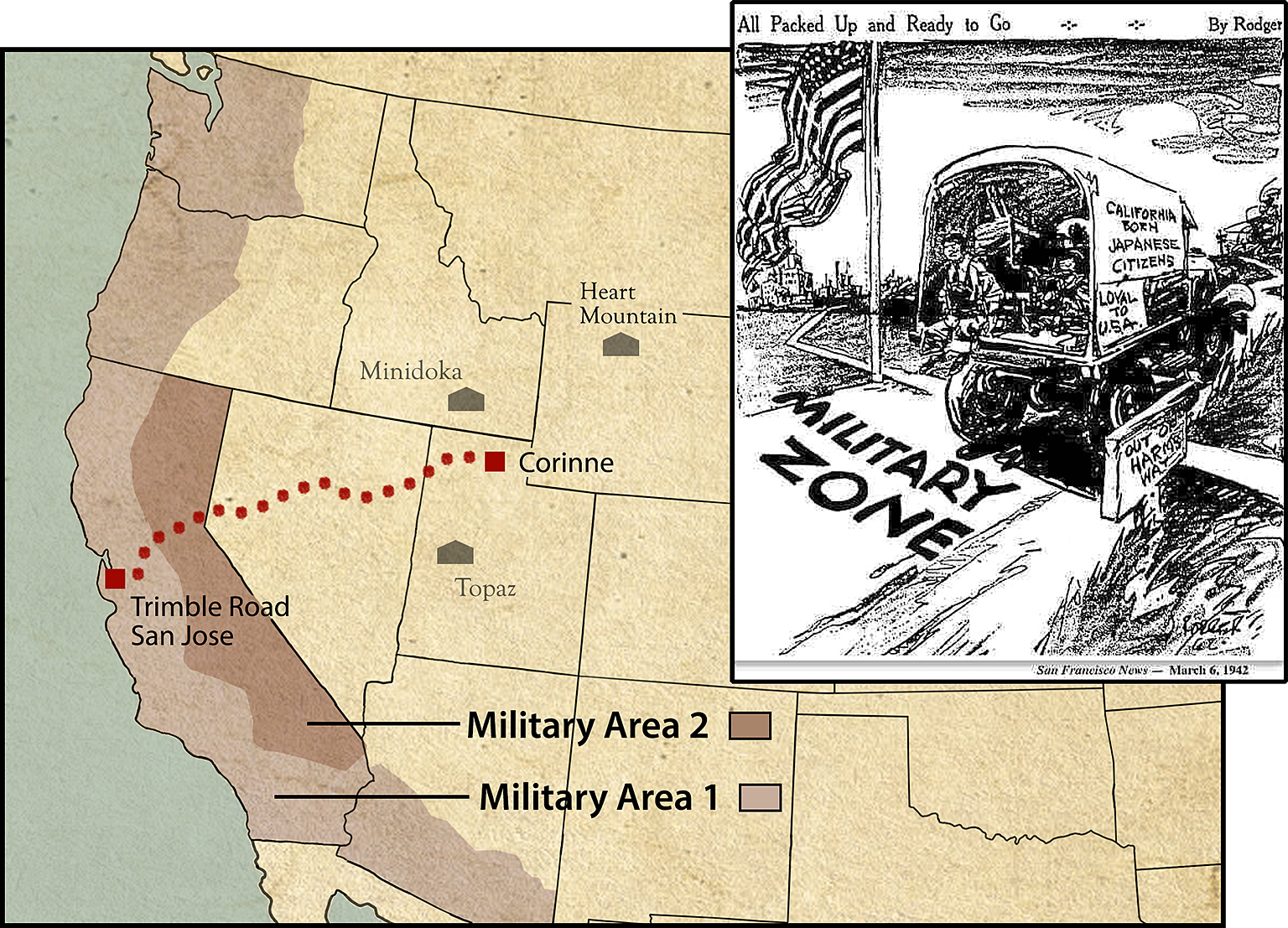

This life of stability was shattered when Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan on Dec. 7, 1941. The Western Defense Command designated the West Coast a military zone and placed curfews and travel restrictions on those of Japanese ancestry.

When President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February, 1942, it became clear that race-based prison camps were looming. But the government also offered an option: self-exile or “voluntary evacuation” out of the newly-created military areas.

Some was pregnant and worried that health conditions would be poor in the camps. She and Izo decided that the family would take their chances and leave San Jose for Corinne, Utah, where they could share crop on land owned by her relatives.

The family of nine hurriedly packed their belongings and boarded a train to Utah in March. They sent the car, a green Plymouth, separately, by freight train.

‘Voluntary evacuees’

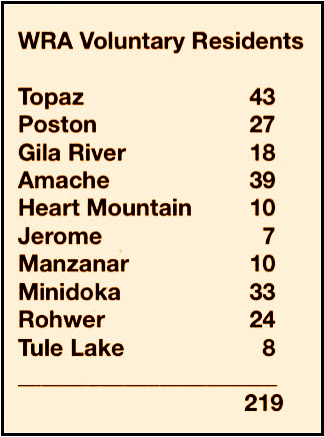

People forced to leave their homes or countries because of war, violence or fear of persecution are categorized as “refugees” or, if forced to move within the borders of their own country, “internally displaced.” The U.S. government came up with its own cruel euphemism for the citizens and permanent residents it forced to leave or be locked up. They called them “voluntary evacuees.”

“Voluntary” didn’t begin to describe the Nakamuras’ forced departure.

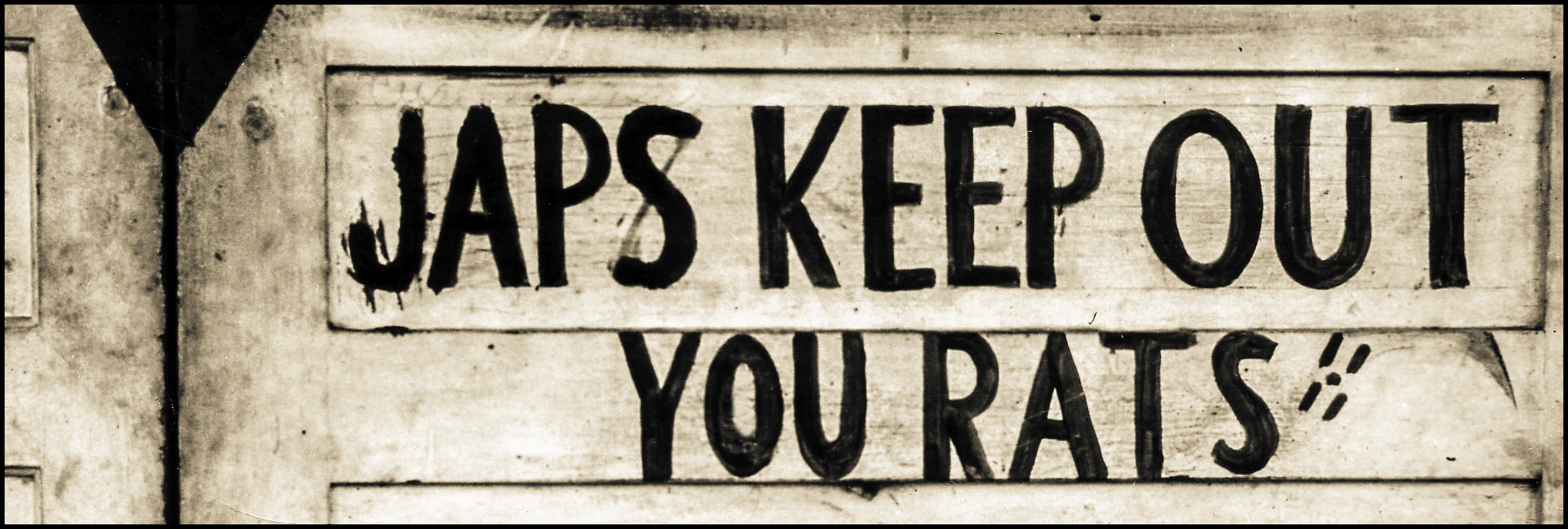

The term masked the desperation of thousands who fled on trains or in trucks with mattresses tied down toward the “white zone” where there would be no friends, few jobs and the threat of vigilante violence.

Violence already was being reported in California, where windows of Japanese American businesses were smashed, a hotel was torched in Sultana and a “guerrilla army of nearly 1,000 farmers” in Northern Tulare County, called the Bald Eagles, armed themselves to “guard” local Japanese Americans.1 At least seven race-based murders took place between December 1941 and March 1942, according to research by historian Brian Niiya.

Citizens and politicians in the states to which Japanese American could flee asked why people who threatened wartime security in California or Oregon wouldn’t be equally dangerous in Idaho or Wyoming. 2 “Japs live like rats, breed like rats, and act like rats,” said Idaho Governor Chase Clark, during this period. 3

In the end, more than 90 percent of Japanese Americans stayed put, although chaos reigned: many Californians headed east within the state only to find themselves trapped when the entire state became part of the exclusion zone.

The period for leaving the West Coast lasted only a month. On March 27, a military freeze order stopped all movement. The Army’s forced mass removal began in spring of 1942.

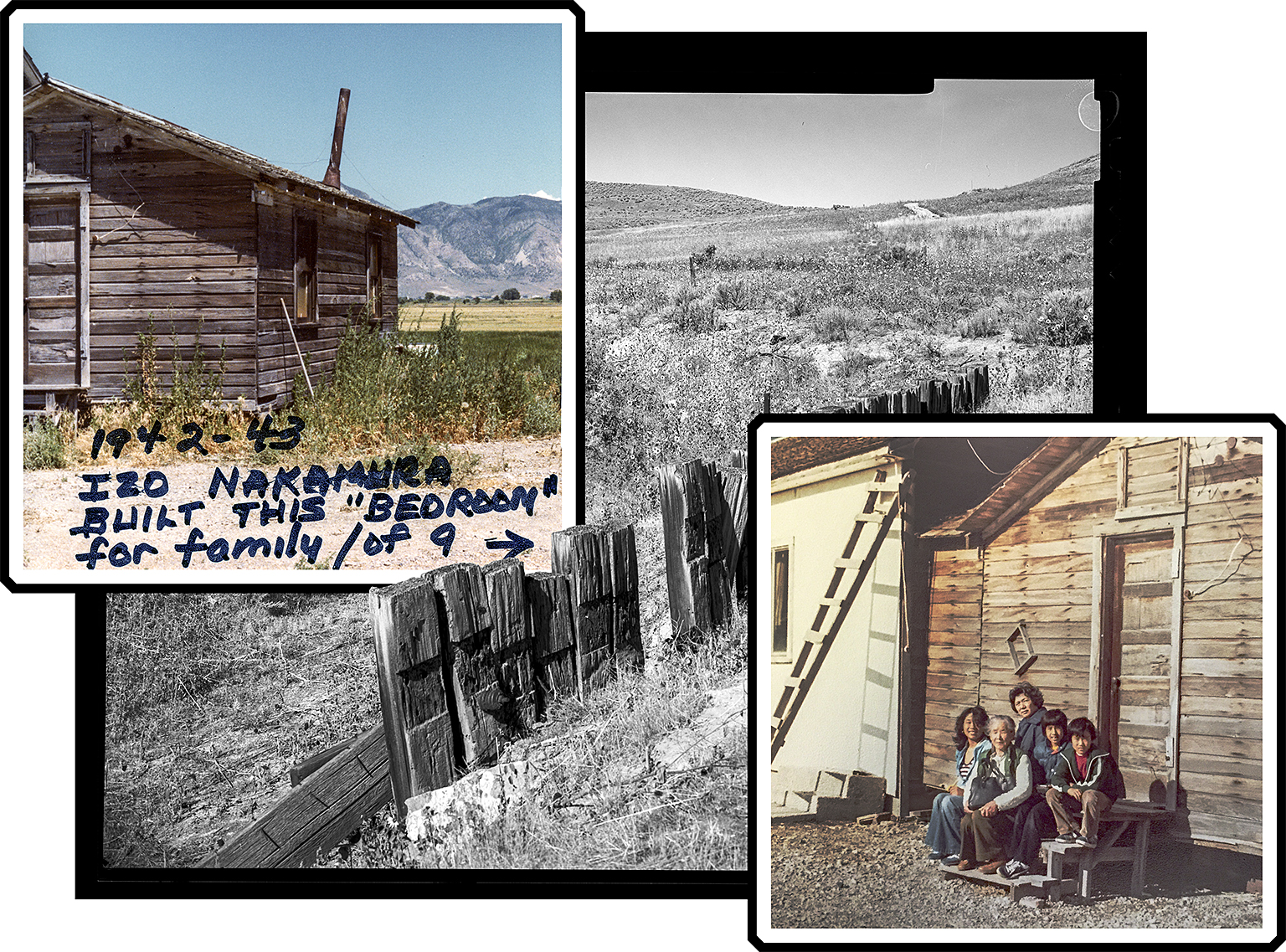

Left color insert: the house that Izo Nakamura built in Corinne for his family of nine.

Right color insert: A post war visit to their relocated cabin, left to right – Colleen Nakamura, Some Nakamura, Alice Nakamura, John Nakamura and Mitchell Matsunaga. The unpainted “bedroom” was originally built by Izo. It was eventually donated and moved next to a church (painted white). Both color photos courtesy of the Nakamura family collection.

The Nakamuras’ exile in Utah began in a primitive cabin with a dirt floor and no running water. They survived the first several months by farming potatoes and sugar beets, but everything changed in October when Bobby, who had just turned 17, died of Rocky Mountain Fever.

Medical treatment was lacking. “The first local doctor wasn’t that helpful, probably because of evacuation,” said Lisa Nakamura, one of Izo’s granddaughters. Bobby was rushed to a Salt Lake City hospital, where he died. He was cremated and his remains were placed in a drawer of the family’s butsudan, a portable Buddhist shrine.

Some had recently given birth to a baby girl and fell into depression. She grieved the loss of Bobby and feared for the health of the baby and the other children. She and Izo began to consider the unthinkable: seeking refuge in one of the prison camps they had left California to avoid.

“Mom didn’t want any of the other children to die. That was the reason why she wanted to go to camp,” said Atsuko Kathleen, who was born a few months before Bobby died. “At least they’d have some health care.”

But entering a concentration camp wasn’t easy.

Izo wrote a letter to the War Relocation Authority, the civilian agency in charge of the camps, to ask if the family could enter one. He also appealed to the head of the Heart Mountain facility in Wyoming, where his sister, Seki, and brother-in-law, George Yamaoka, were incarcerated. On Dec. 22, Heart Mountain director Guy Robertson replied that it was “impossible to make room for an additional family … (but) we will keep your application on file.” He advised the Nakamuras to apply to the Topaz camp in Utah. Meanwhile, the WRA suggested they write to the Minidoka facility in Idaho.

Since the Nakamuras were already in Utah, they decided to apply to Topaz. Izo asked for help from a friend, Fred Wada, who had set up a colony in Keetley, Utah, of 130 Japanese Americans who had caravanned out of California before the freeze order.

Izo’s handwritten letter and other documents were found in his Evacuee Case File.7

Wada wrote to Topaz director Charles Ernst on Jan. 17, 1943. “Here I am again asking you for another favor.”

Wada explained that after the Nakamuras’ son died, “they asked me to let them into our group, but I am not in favor of a little Tokyo in Keetley … Will you kindly accept this family into your project? The members of this family and their ages are as follows: Izo Nakamura, 56; mother, Some Nakamura, 44; sons – James, 21, Henry, 15, and Ray, 10; daughters – Betty (sic), 20, Yoriko, 13, Michiko, 7, and Kathleen, four months.”

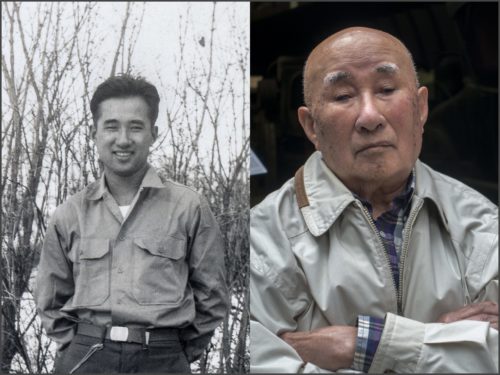

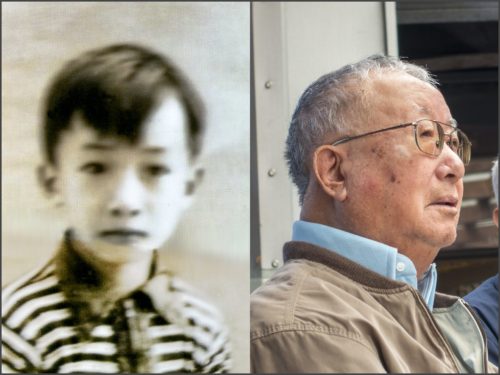

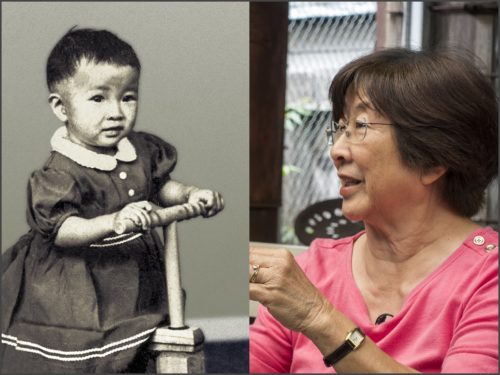

Izo and Some’s children

Izo also wrote to Ernst, explaining, “After the death of our son recently, my wife hasn’t been herself … She gets hysterical … we feel that if she is with her friends in your project she might get better. So could it be possible for you to give us permission to reside in your center immediately. Thank you kindly.”

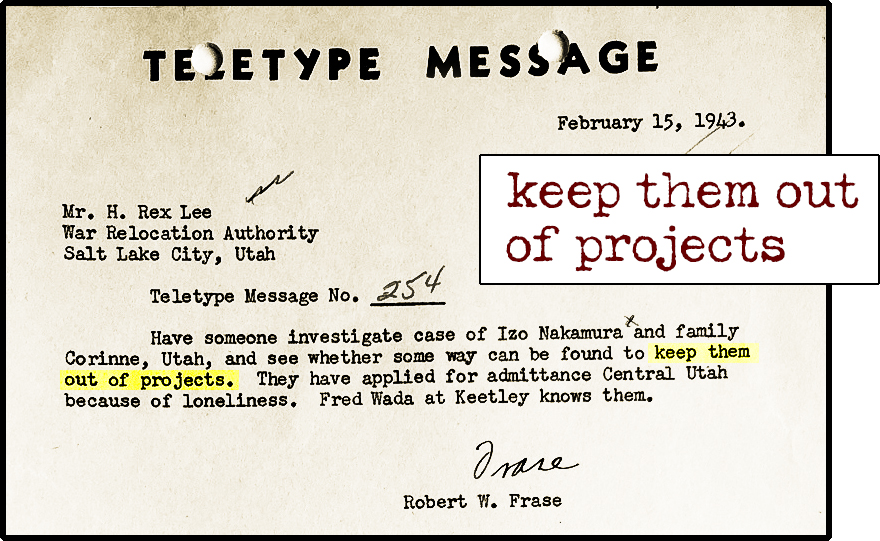

Unbeknownst to the Nakamuras, their case was under discussion by WRA officials in Washington, D.C. and Utah.

Robert Frase, a WRA official in Washington, D.C., sent a telegram to the Salt Lake City office, asking someone to “investigate case of Izo Nakamura and family Corinne, Utah, and see whether some way can be found to keep them out of projects.”

Some ten days later, W.E. Rawling, WRA Assistant Relocation Supervisor, Salt Lake City, replied to Frase with a report.

“In reply to your telegram concerning the Izo Nakamura family at Corinne, Utah, I visited this family…

“They are voluntary evacuees coming to Utah from San Jose, California, on March 29, 1942.

“Mr. Nakamura is 56 years old and claims to be in poor health and unable to do ordinary farm work. Mrs. Nakamura is 44 years old and the family claims she is mentally unbalanced since the death of her son in October.

“Their contention is that with the one boy, James, 22 years old, as the only worker in the family able to operate the farm and do heavy work, that it is impossible for them to share-crop this year and provide a living for such a large family.

“They tell me that they are not destitute as yet because they did make some money last year on farm operations. They have a car, and there was an ample supply of coal in their home. They appeared well dressed…

“In my opinion these people have decided they would like to have the entire family admitted to a center in order that they can have free board and lodging and thereby save any money that they have now on hand.”

Frase also wrote directly to Ernst.

“We have had quite a number of these cases investigated and in practically all of them it has been possible to arrange for the continued residence of the applicants outside relocation centers.”

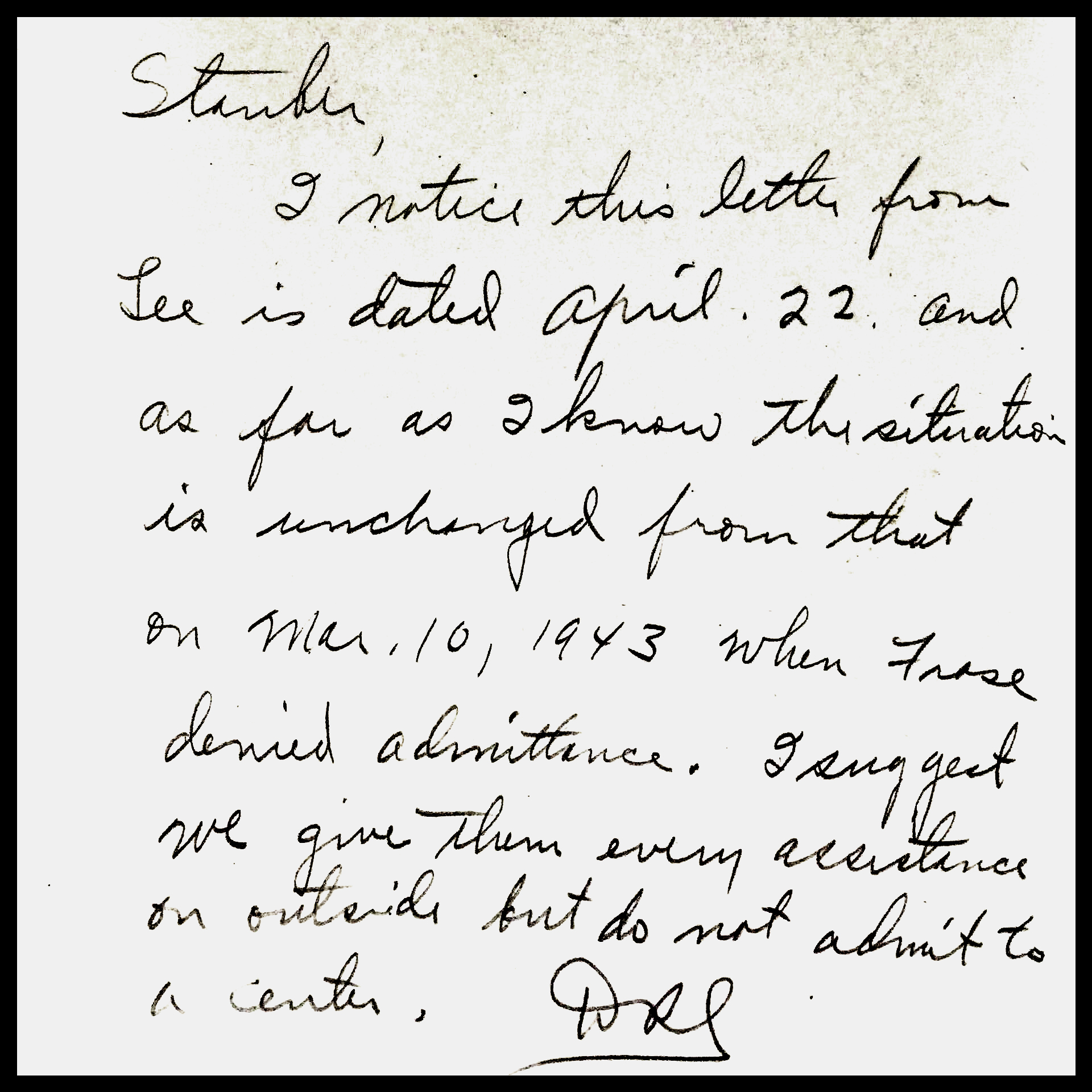

Even WRA director Dillon S. Myer appears to have weighed in on the case. An undated note signed with his initials and in handwriting similar to that of his states: “I suggest we give them every assistance on outside but do not admit to a center.”

A social worker at Topaz, George Lafabreque, was the only official voice of sympathy.

Lafabregue wrote to Ernst on March 16: “The eldest son of the family, James Nakamura, visited our center recently … This family has suffered more than the usual evacuees, and although we are not in favor of making a Relocation Center a refuge for unfortunate evacuee families, we believe that for the welfare of the family concerned, consideration should be shown to their request.”

Three months later, the Nakamuras were admitted into Topaz. They were assigned to Block 36, Barrack 7-E, next to the unit where James Hatsuaki Wakasa, an issei chef, had lived before he was shot and killed by a guard, eight weeks earlier.

Henry, the middle child, attended high school at Topaz. Decades later, he told his children that camp was “fun.”

Henry’s daughter, Lisa, a sansei who was born after the war, realized that compared to the trauma her father had experienced before and after Topaz, life in camp might have seemed “fun.”

Hardship continued after the war. The Nakamuras returned to a different part of San Jose and started to farm again. “It was hard,” said Henry. Bobby’s ashes were finally laid to rest at the Oak Hill Memorial Park cemetery.

There was only enough money to send one child to college. The youngest, Ray, who was 10 when he entered Topaz, was selected as the child with the most academic promise. He was accepted into Stanford University. But Ray had a breakdown in his last semester and never graduated.

“I once talked to Uncle Ray about this,” Lisa said, “and his story was that despite the family sacrificing so much money for his college, the prospective job offers were paltry in pay, which is ‘what made me sick.’”

“The generational trauma from financial loss really echoes,” Lisa said. Ray later suffered from schizophrenia, she said, but he stayed close to family and attended every gathering.

Lisa became a clinical psychologist, specializing in intergenerational trauma. She wrote her doctoral dissertation in clinical psychology on the healing effects for those who attended the pilgrimage to Tule Lake, and became a “healing circle” leader for the Tsuru for Solidarity immigrant rights advocacy movement. In 2021, Lisa joined a Tsuru letter-writing campaign to support H.R. 40, a Congressional bill that would establish a commission to study Black reparations. She cited her family’s experience of incarceration.

“Intergenerational trauma has impacted our family. Financial issues have become a loaded issue after seeing it be a source of contention during and after the war. My relatives suffered from psychological trauma that can manifest as hoarding, feelings of deprivation and resulting envy, and avoidance to such a degree as to be unable to stand up for personal injustices,” she wrote.

Survivors gather with descendants to remember

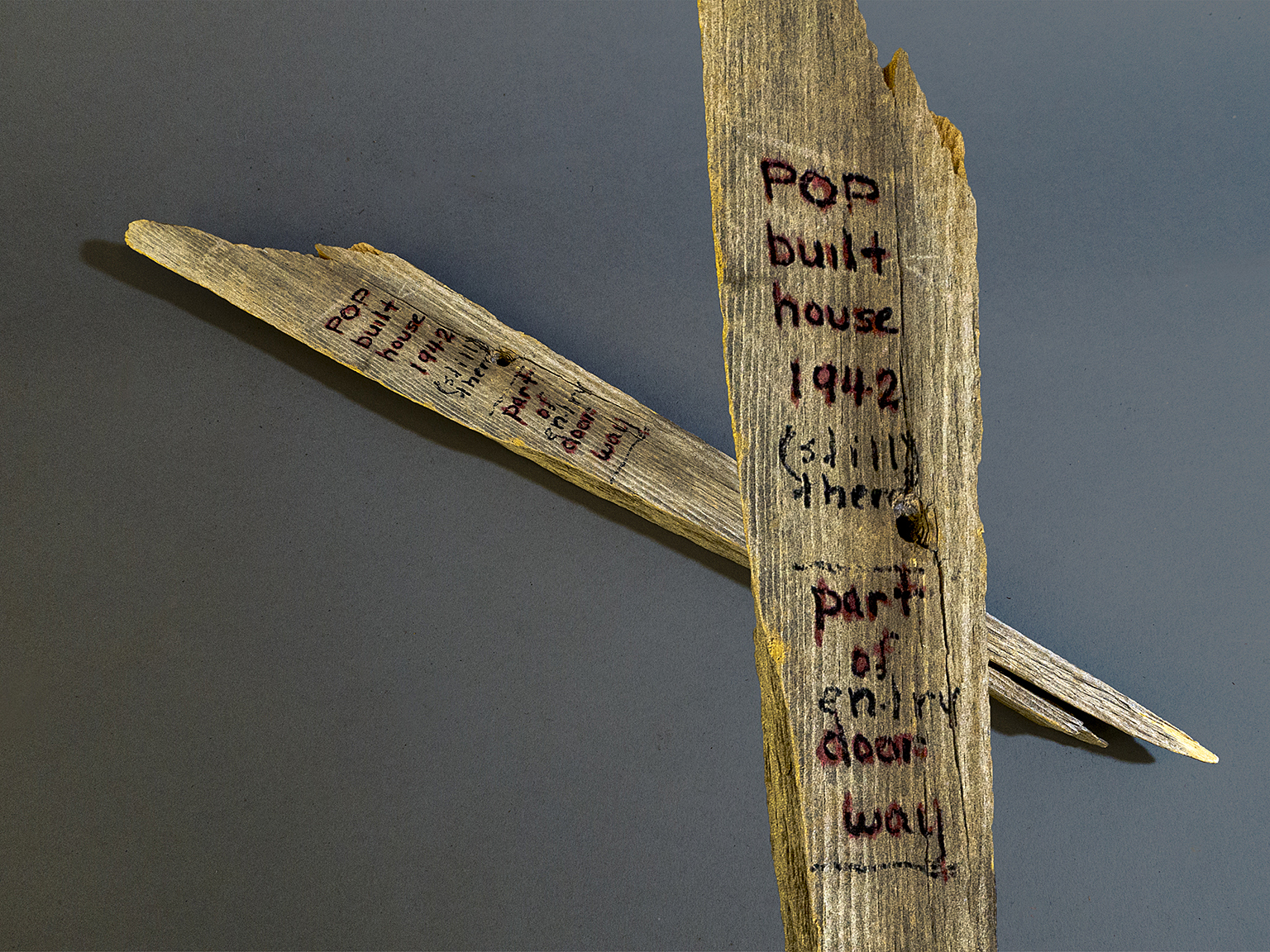

In 2017, family members gathered at the Japanese American Museum of San Jose to listen to seven of the last surviving nisei siblings talk about the war years. The elders brought trunks, documents, photos and World War II artifacts. A wood fragment from the door frame of the Corinne shelter was passed around, a memento from the family’s return to the site. “I bought my Toyota Sienna so all seven of us could travel. And that’s what we do,” said Rosie.

Nieces and nephews read aloud excerpts from Izo’s government file, animating the words of their ancestors and those of government officials who almost succeeded in excluding their family a second time.

Atsuko was ten months old when she entered Topaz. She listened to her siblings’ memories and located Trimble Road on a map at the museum.

She also shared a story that was preserved not in Izo’s file but in family memories.

The story was about Bobby, she said. Older siblings had told her that before he died in the hospital, he reached out from his bed to gently stroke her head and say how sweet his baby sister was.

Dedicated to the memory of Bobby, Some and Izo, and the three Nakamura children who attended the San Jose museum reunion in 2017: James, the eldest, who drove to Topaz to request that officials allow the family in, and Bettie and Ray. With gratitude to Henry, Rosie, Atsuko and Alice for their time and support.

Documentary and news reports

Documentary: Before They Take Us Away, directed by Antonia Grace Glenn. The award-winning film can be seen at the PBS website.

CBS Bay Area news report by Ryan Yamamoto whose father was a child in the Keetley Colony, Utah. January 30, 2023.

Credits

October 24, 2023

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: Nancy Ukai, David Izu, and the Nakamura family

Special thanks to:

Lisa Nakamura, the Nakamura family, Tom Izu, Russell Endo, Japanese American Museum of San Jose, Jim Nagareda, Allyn Emiko Izu, Susan Hayase, Richard Cahan, Densho.

Supported by a grant from the Japanese American Confinements Sites program of the National Park Service