At the former Topaz concentration camp in Utah, there’s only dry grass where a concrete monument once stood, to mark where an innocent man was killed by a guard tower sentry. The man was walking his dog after dinner. HIs name was James Hatsuaki Wakasa.

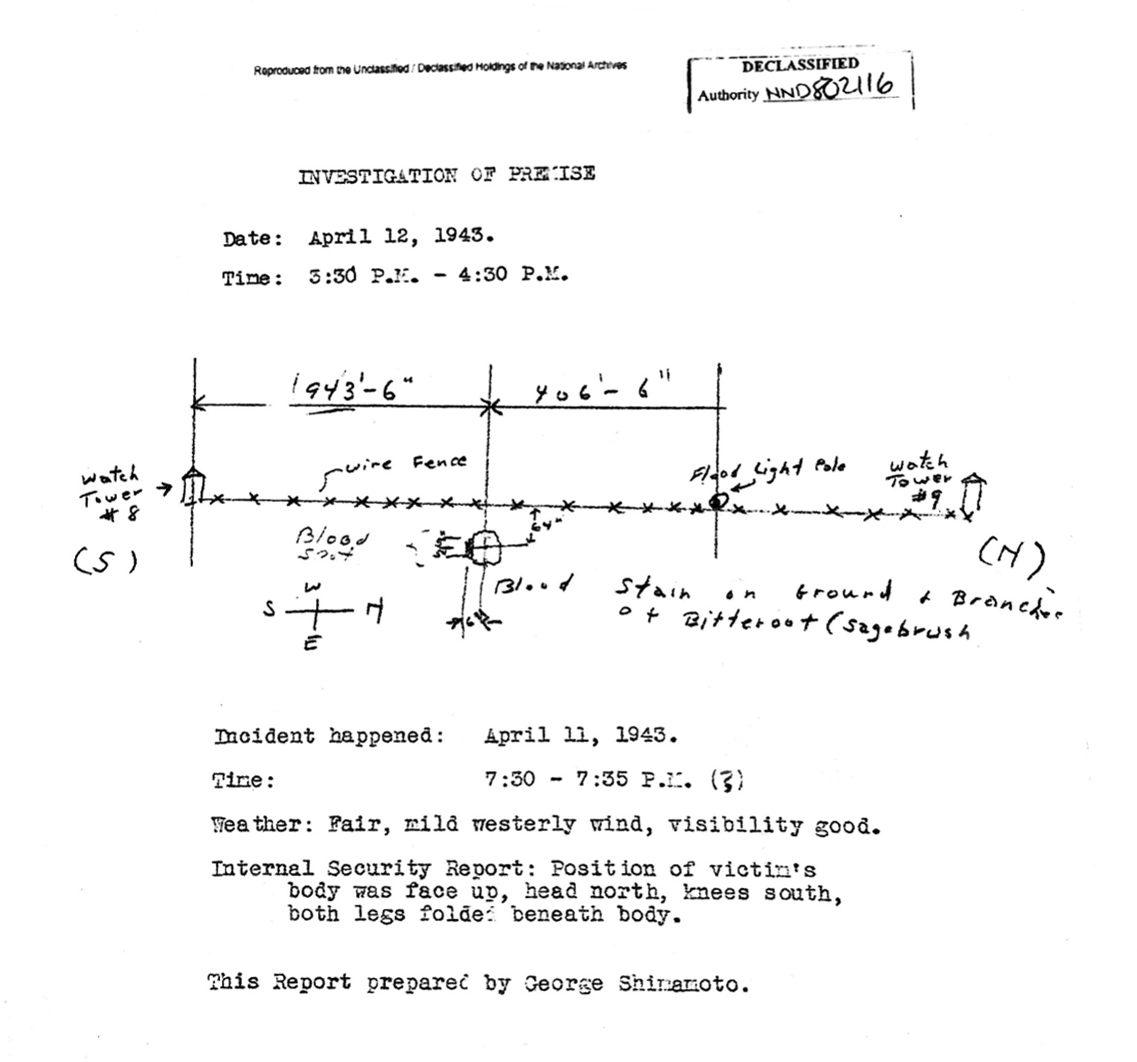

According to military records, a sentry from North Carolina shot his 30-30 Springfield rifle at Wakasa from a distance of 250 yards, the length of two-and-a-half football fields.

Private First Class Gerald Boone Philpott, 19, fired with pinpoint-accuracy a single shot that struck Wakasa, 63, in the chest, piercing his heart and severing his spinal cord. But Philpott testified in his court martial, “I did not aim the shot sir.”1

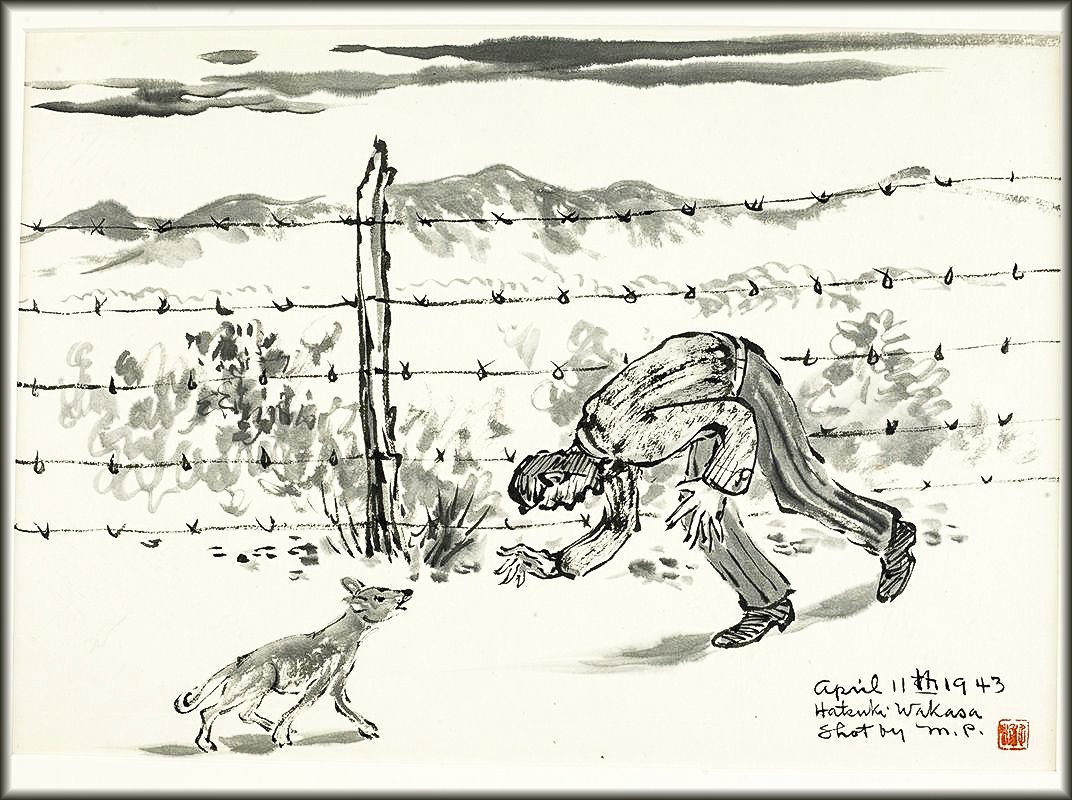

The shot knocked Wakasa to his knees. He fell backward and died parallel to the fence at 7:30 p.m., Sunday, April 11, 1943.

Weeks later, despite orders not to build a monument, angry issei prisoners erected one where Wakasa died.

It memorialized a tragedy, called attention to a military homicide and was unauthorized. When Topaz officials and the War Department learned of the monument, the builders were forced to tear it down.

In recent months, historical statues of Confederate generals that have stood for decades have been toppled during mass uprisings. But what of monuments to racial or state-sponsored violence that never got built, or were erected and demolished, to erase a dark history?

At least seven Japanese immigrants and American citizens were killed by military gunfire in U.S. concentration camps but their deaths are little remembered, in part because there are no markers.

The Wakasa monument was created as a permanent memorial to injustice but it lasted only days.

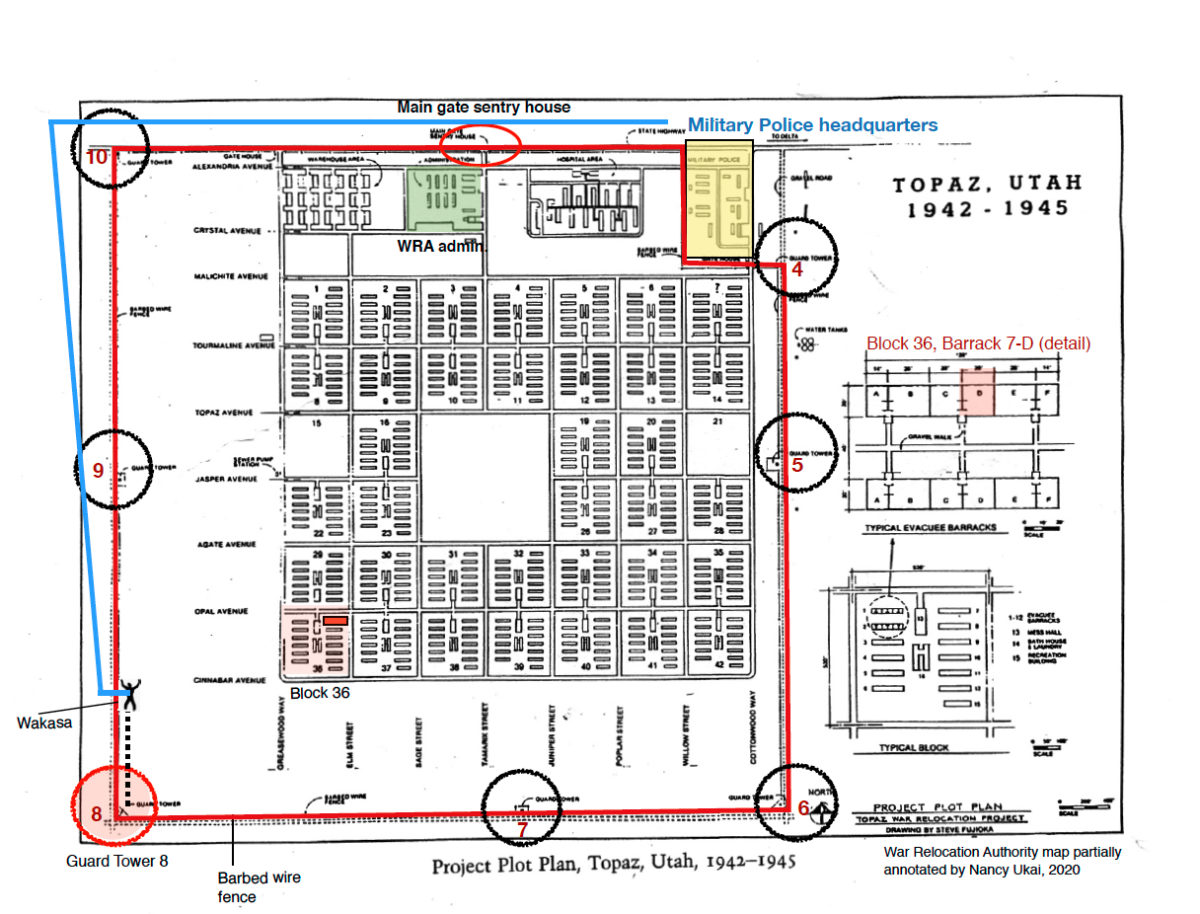

Wakasa died facing guard tower 8, in the southwest corner of the camp, leaving a large blood stain in the soil, three to five feet inside the fence, according to military and War Relocation Authority records.3

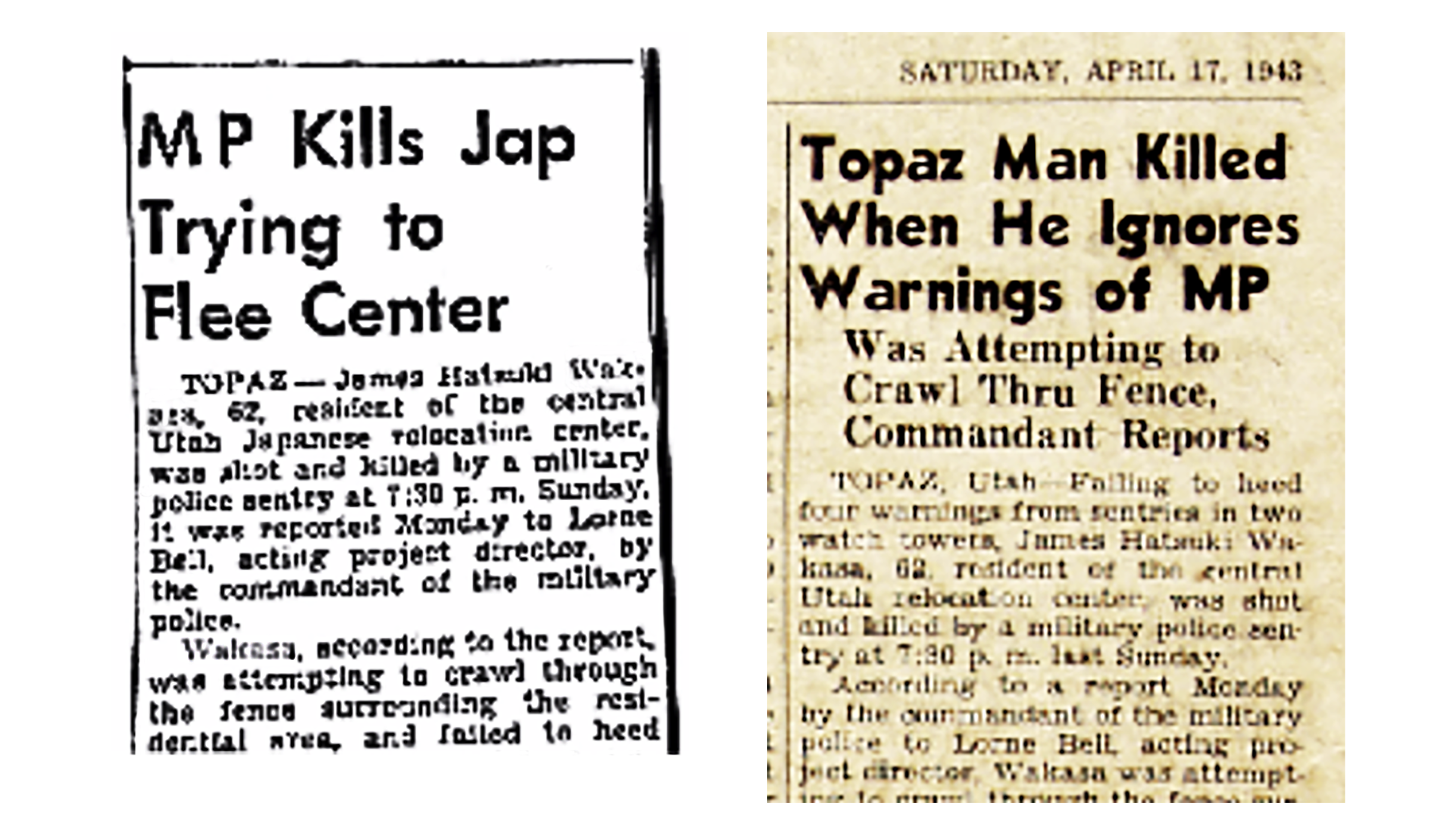

The official report for public distribution, however, stated that Wakasa had been attempting to “crawl through the fence” after ignoring four verbal calls to halt.4 The whitewashed version, which was written by Topaz reports official Russell Bankson, and cleared for approval by the Office of War Information, was never corrected.

The military took charge immediately after the shooting. The fence was under its jurisdiction but everything inside it was controlled by the civilian WRA. Nevertheless, soldiers seized Wakasa’s body and drove it to the Military Police headquarters on the other side of camp.

Topaz WRA officials did not learn of the homicide for 45 minutes.

That night, the commanding Army officer denied the Millard County sheriff’s request to carry out an inquest. Early admissions by the military that a warning shot had not been fired were dropped. The Topaz Times camp newspaper reported scant information. Wrote Miné Okubo, “Facts of the matter were never satisfactorily disclosed to the residents.”7

The shooting meant that “we were helpless. There was no way of defending ourselves from anybody who just got trigger happy and wanted to shoot us,” Michi Kobi said.8

Angry and scared inmates armed themselves the next morning with “a club or anything that could be used as a weapon,” Mel Roper, a Topaz teacher recalled. “It looked for a while like there might be a revolution within the camp.”11

The inmates were met by soldiers armed with machine guns, tear gas and anti-riot weapons. The riot gear order was lifted two days later but work stoppages continued and prisoners held emergency meetings.

A camp-wide committee of two representatives from each of 34 blocks was formed and then reduced to a Committee of Fifteen composed of 10 issei and five nisei. An additional nisei was added, from the Community Council, to act as interpreter for the immigrant members.

The committee brought demands to camp director Charles Ernst for a civil trial, that the funeral be held where Wakasa was killed, and that a monument be built there. All requests were denied.

The administration called the denial an “agreement.”

A funeral in Japanese was instead held half a mile from the fence on April 19, under a beating sun, before a crowd of some 2,000. A group of women had created paper flowers and fashioned them into 30 wreaths and funeral ornaments.

Wakasa’s remains were taken to Ogden to be cremated. On May 10, Bankson wrote a report in which he declared, “The Wakasa incident has now been closed.” 13

He noted that Philpott had been “honorably” acquitted of manslaughter in a court martial at Fort Douglas on April 28, 17 days after the shooting. The conclusion was never conveyed to Topaz inmates.

By 1947, Philpott was back in his hometown of Durham, North Carolina, working for the police department.15

But around the time that Bankson was finishing his report, issei men on an agricultural crew, in violation of orders, were building a monument where Wakasa died, using a sack and a half of stolen government cement to which they added native rocks.

Army and Topaz officials took photographs of the monument and military photos were sent to Washington, D.C. This created alarm at the highest levels of government; officials worried that Japan would cite the killing as a U.S. atrocity16 and mistreat U.S. prisoners of war. Also, the situation in the camps was tense. Topaz had only been open seven months when Wakasa was killed and his death came four months after an uprising at Manzanar in which two prisoners were slain. Topaz was still in turmoil over the loyalty questionnaire.

Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy wrote on June 8 to WRA director Dillon Myer that Wakasa’s homicide was “a justifiable military action and it seems most inappropriate that a monument be erected to him.”19 By then, the monument had come down, but McCloy complained that “there was no removal of the construction material.”

Ernst assured McCloy that “the monument has been torn down and the rocks which were used … have been completely removed from sight.”20

Topaz officials had been corresponding internally about the controversial marker. Assistant camp director James Hughes contentedly described to Ernst, who was away, how he had induced cooperation.

“You will be amused to learn that two members of the agricultural landscape crew, undoubtedly backed by someone else interested in the Wakasa case, went ahead and violated our terms of agreement with the committee by constructing a monument at the site of the incident. I haven’t seen it and I don’t intend to, but word reaches me that it is quite an impressive affair.”23

Hughes decided to talk with two members of the Committee of Fifteen to discuss the violation of the director’s order. “Two days later we found the monument was practically completed. My action then consisted of calling this fact to the attention of the committee members who had worked with me.”

Hughes told them the monument was “a physical symbol of the first case where an agreement had been broken by any committee of residents.”

“Since the matter was placed completely in their hands,” he wrote to Ernst, “they wrestled with the problem for almost three days, and yesterday came to the office to state that the commitee was embarrassed, and was very anxious to live up strictly to the terms agreeable with you, and that the landscape crew had been directed to remove the monument.”

It took the committee nearly three days to capitulate to the humiliating ultimatum. The monument incident lasted a week to 10 days.

It’s unlikely that others in the camp knew much about the monument since reports were not published in the Topaz Times, which was censored, and because Wakasa was single and without grieving family members to keep his case alive. In the end, the monument was as ephemeral as paper flowers.

In later years, the only visual documentation of Wakasa’s death has been WRA photographs of the funeral and artworks created by artists Okubo and Chiura Obata, director of the Topaz Art School.

Searches at the National Archives have not yet located the Army or WRA photographs of the memorial. As a result of the government’s control of the facts and objects, memories have been stolen.

Myths, such as stories that Wakasa was deaf and could not hear the sentry’s alleged verbal warnings, have persisted. The claim of deafness was used by State Department officials to absolve the sentry of blame.25 But there are many accounts by friends and officials of conversations with Wakasa that refute this claim.

In his file at the National Archives, a legal memo mentions in passing that Wakasa was “a little hard of hearing” but that he frequently visited the camp office to discuss his case against the state of California to receive unemployment benefits.

Wakasa did not want a bad precedent to be set, a legal officer wrote. “He was not concerned about the few dollars involved … but was acting because he had the interests of the community at heart.”26

At the time of his death, Wakasa had lived in the U.S. for two-thirds of his life. He had traveled widely, living in Chicago for 14 years, and also in St. Louis, Detroit, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. He may have traveled to Mexico; 360 pesos were found among his belongings.

He was perhaps one of the most highly educated issei at Topaz. Wakasa was born in 1880 in Ishikawa Prefecture and attended the elite Kōgyokusha prep school in Tokyo before entering Keio University, whose founder, Yukichi Fukuzawa, famously urged young Japanese to study Western learning. Wakasa kept a portrait of Abraham Lincoln in his barrack.

Wakasa emigrated to the United States in 1903 and studied at Hyde Park High School in Chicago and pursued post-graduate work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 1917, despite his education, he was working as a civilian cooking instructor during World War I at Camp Dodge in Des Moines, Iowa.

When the U.S. entered World War II, Wakasa was living in San Francisco and got caught up in the forced removal of Japanese and Japanese Americans to the Tanforan racetrack in April, 1942.

Five months later, he was shipped to Utah. The day before he died, the WRA agreed to support his legal claim for unemployment benefits.

Wakasa probably didn’t know how dangerous it was to stroll near the fence. Military records show that eight sentries had shot at people in the four months leading up to his fatal shooting,29 citing “JAP … failed to halt” or “was crawling under the fence,” but these firings were not reported in the camp news.

At least three of the sentry shots were along the west fence, a quarter mile from Wakasa’s quarters at 7-D, in Block 36. “My father and mother said he had a dog and always took him for a stroll near the fence,” recalled Miyoko Nakagawa. “Since he was in Block 36, the desert was very appropriate for his dog to walk around.”30

At the camp today, there is only parched earth where the monument once stood. Over the years, people have created informal markers, although not at the place where Wakasa died, since that location has not been known.

A provisional marker was erected by a local Boy Scout troop. In 2015, a student at the White River Academy built a sign near the west fence. A light blue, hand-lettered plaque has hung for years at the camp’s former sewage plant, on the concrete foundation.

Given that a 1943 map of the murder site provides information about where Wakasa was killed, perhaps it is time for the razed monument to be resurrected.

| Wakasa Monument | |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | Unknown |

| Material | Cement and native stones |

| Date | mid-May, 1943 |

| Creators | Immigrant men, agricultural landscape crew |

| Site | Topaz, Utah, inside the west fence, between Guard Towers 8 and 9 |

| Records | National Archives, Washington,D.C.; JASC, Chicago, IL; Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City |

Credits

September 15, 2020

by: Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

banner cover design: David Izu

banner cover images: David Izu, Yone Ito, National Archives, Nancy Ukai and unknown photographers

Special thanks to:

Jeff Burton, Chang Kim, John Kusano, Maxston Young, Kaylene Young, White River Academy, Michael Takada, Maria Pimentel, JASC, Densho, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, National Park Service, Topaz Museum, Ken Verdoia, Duncan Williams, Mollie Pressler, Bruce Embrey

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites program