When its owner was forced to leave his home, taking only what he could carry, the bonsai was left behind.

It was well over five feet tall, unusual for a bonsai. Neglected for three years, the tree burst through the slats of its wooden planter, sending shoots into the earth. When the owner returned, he began to nurse the tree back to health and its proper form, a challenge and a pleasure that continued for four decades.

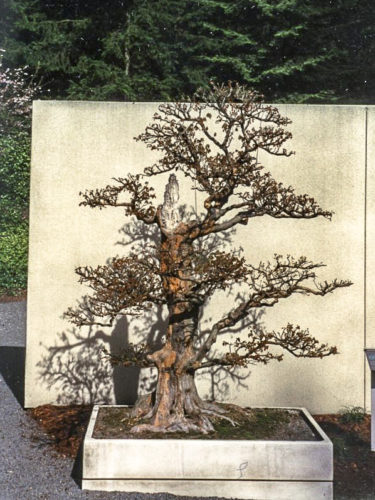

The prize specimen, a trident maple, is now some 200 years old and the star of an outdoor bonsai museum in the Pacific Northwest. It has outlived several generations of humans who cared for it and artistically guided its growth.

The war was only one part of its long life and, like all survivors, it has a story to tell.

Born in Japan

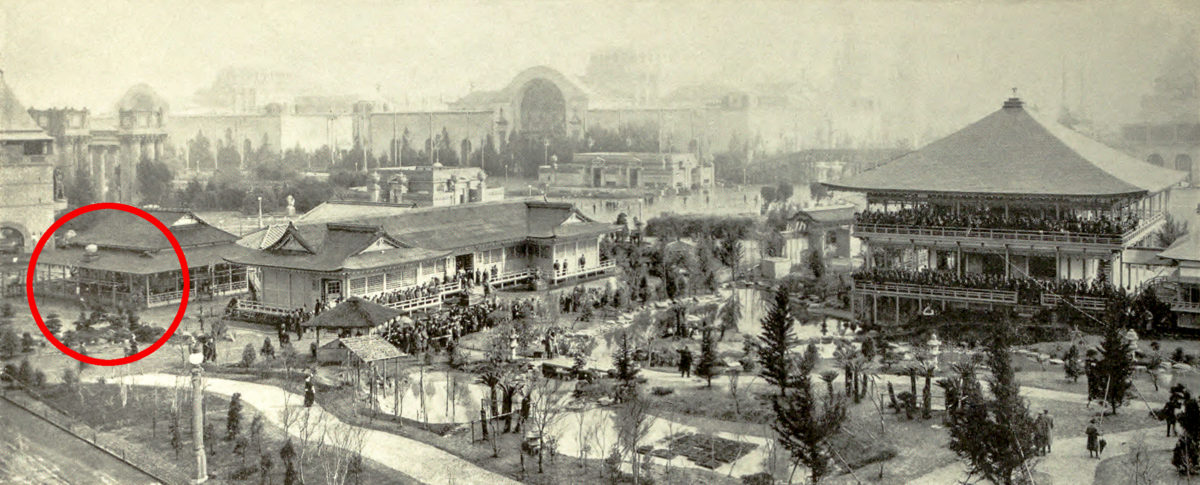

The bonsai began its life as a pampered plant in Japan around 1815.1 It was trained into such a handsome specimen that by the time it was approximately a century old and perhaps four feet tall, it was selected to represent Japan in a world’s fair. The Yokohama Nursery Co. loaded it onto a steamship bound for California.

The bonsai — a tree that has been carefully cultivated in a container to curb its growth and intensify its beauty — arrived in San Francisco in 1913, two years before the opening of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. It was “imperial size” and one of a matching pair.

From its perch on the verandah of the Formosa Tea House in the Japan pavilion, the exotic plant in a pot delighted guests who sipped tea served by women in kimono. Its partner tree was sent to San Diego for display in another exposition.

The S.F. world’s fair was successful beyond expectation, attended by 19 million. The maple won acclaim and would have been purchased by the wealthy Du Pont family on the East Coast had the pair not been divided, causing the Du Ponts to lose interest. This turn of events led to the bonsai being acquired by Kanetaro Domoto, a wealthy immigrant from Wakayama, Japan. He lived in Oakland.

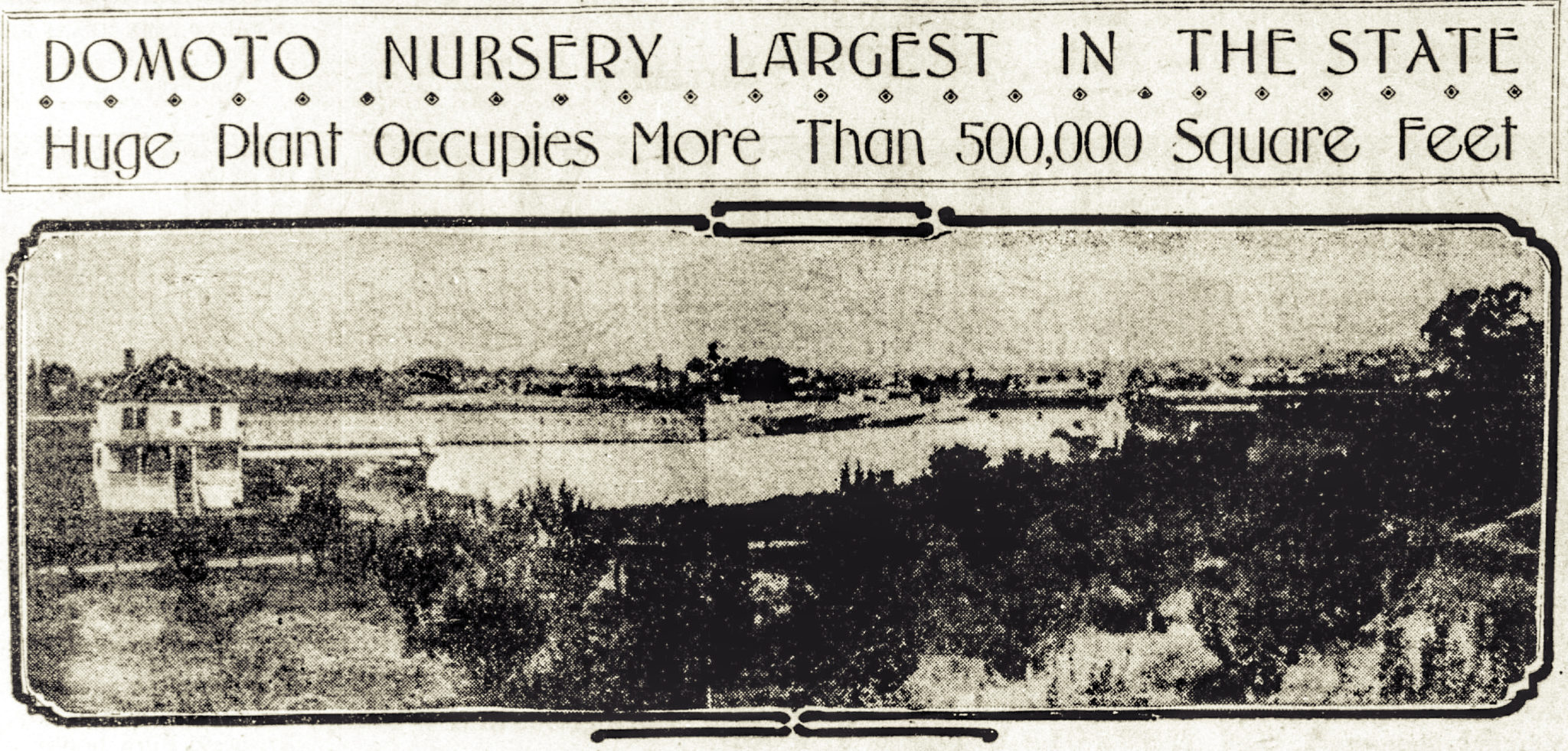

Kanetaro was an entrepreneur and a successful businessman who owned 48 acres in the Fitchburg district of Oakland with his brothers. They would have been among the first Japanese to buy land in California, having purchased it before the discriminatory Alien Land Law was passed in 1913 that banned Japanese immigrants from buying property.

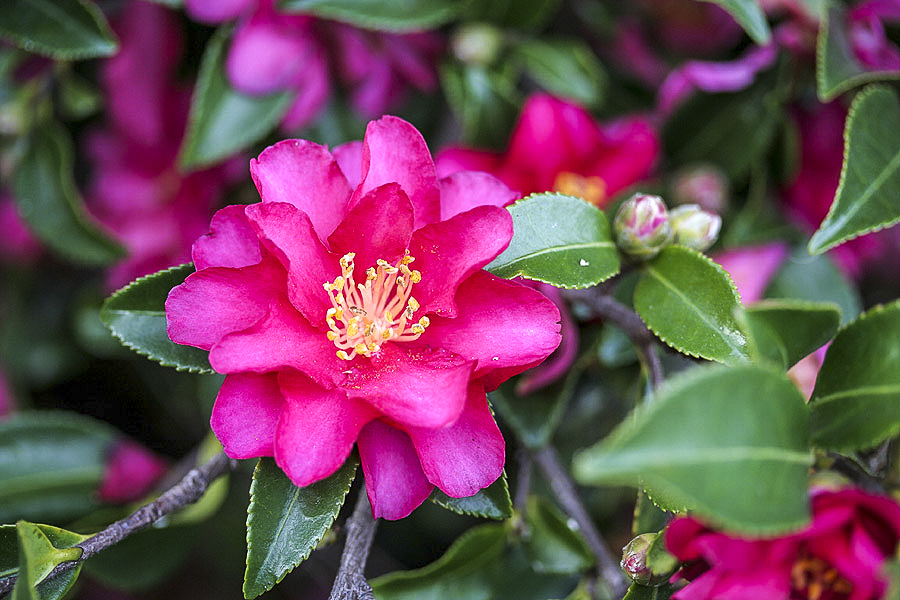

The Domoto Brothers Nursery grew into one of the first large-scale commercial nurseries in California, famed for their beautiful and rare plants, bulbs and seeds imported from Japan, Australia and Europe.3 The 1902 catalogue offered 230 varieties of chrysanthemums.4 The Domotos introduced azaleas, camellias and the persimmon into the U.S. and shared their expert knowledge so generously with their fellow immigrants that white growers called their operation the “Domoto College.”5

from the San Francisco Call Bulletin, 1912.

Saved during the Depression

But the prized tree was nearly lost during the Depression. The bank foreclosed on the massive Domoto property and by 1936, when the city of Oakland had taken over the land, it was described by a local newspaper as having turned into “a jungle” of 35,000 rose bushes, a goldfish pond and 80,000 greenhouse glass panes.9 Everything had been lost except for the bonsai. Kanetaro handed the tree down to Toichi, the oldest of 13 Domoto children.

Toichi was born at home on Dec. 11, 1902, just as the noon whistle blew, “so I even know the exact time of birth.”11 In adulthood, he continued in the nursery business, although that wasn’t his first choice.

He had enrolled at Stanford University in 1921 with the goal of studying mechanical engineering. But jobs in that field were essentially closed to Japanese Americans, so after two years, Toichi transferred to the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign to study horticulture.

Upon returning to California in 1926, Toichi bought 26 acres in Hayward to start a nursery and the tree was moved onto his property.

On Dec. 7, 1941, Toichi was sitting with a bank manager when they heard that the Japanese military had bombed Pearl Harbor. He recalls that the manager said, “Toichi, I don’t know. It looks bad.” 13

Immediately after the bombing, a sheriff’s deputy came to his house to ask for the names of espionage suspects. Law enforcement already had names of San Francisco Flower Market members, Toichi said, and “most of the active members were picked up and sent to detention camps for the alien Japanese, so-called.”14 Several Domoto family members decided to leave the area during a period when Japanese Americans were urged by the government to “voluntarily” depart from their homes in advance of an expected mass removal.

The tree had to be left behind. Toichi, with his wife Alice Okamoto, who was pregnant; Kanetaro, now a widower; and Toichi’s brother and sister-in-law, fled 100 miles to the eastern half of California. The area was not under military control and they hoped to wait out the war in Livingston, where a sister lived.

But the entire state shortly thereafter became off limits to all American Japanese and the family was forcibly exiled twice: first to a temporary detention site in Merced, for six months, and then to the Amache concentration camp in Granada, Colorado.

Toichi and Alice’s first child, Marilyn, was born the day before removal to the first camp and Kanetaro died at age 77 in the second one. When Toichi received permission to travel to Oakland for the burial of his father’s remains, he had to pay for a guard to escort him.15

photo: courtesy of the Pacific Bonsai Museum

Breaking free from its box

The bonsai had been left in the care of Toichi’s nursery employee in Hayward, but it was not carefully tended during the war and the tree broke out of its box and sent roots into the ground.

Toichi returned to Hayward after the war and began the decades-long process of returning his deceased father’s tree to a semblance of its original form.

He also started to rebuild the business, arriving at 6 a.m. to pick up plant stock from a sympathetic white nurseryman who agreed to sell to him. When Julius Nuccio asked Toichi why he set the pickup time at dawn, “His reply was that he didn’t want anyone to see a Japanese in our nursery for fear of hurting our business,” Nuccio said.19

In succeeding years, Toichi became known for his innovative work hybridizing camellias, sasanqua, tree peonies, azaleas and other plants and blossoming shrubs. He was elected president of the California Horticultural Society in 1957 and was known for his knowledge and his willingness to share it.

But friendships were his most important life achievement, he told an oral historian.”The fact that I got to know certain people real well, intimately, so that regardless of their color, race or religion, I knew them as a person, I think that was (what) I really cherish more than anything else.”20

“If you’re really truly interested” in certain plant material, he said, “you forget who is selling, and you go to the source, and you get what you can. You forget about race or color… That’s the way I felt. And then in the interim, since it’s the material that they’re interested in, there is common interest, they get talking about it, and you find out, ‘Oh, he’s not such a bad guy to talk with.’

“When you are out working with plants and flowers, you can’t have hate in your heart.”23

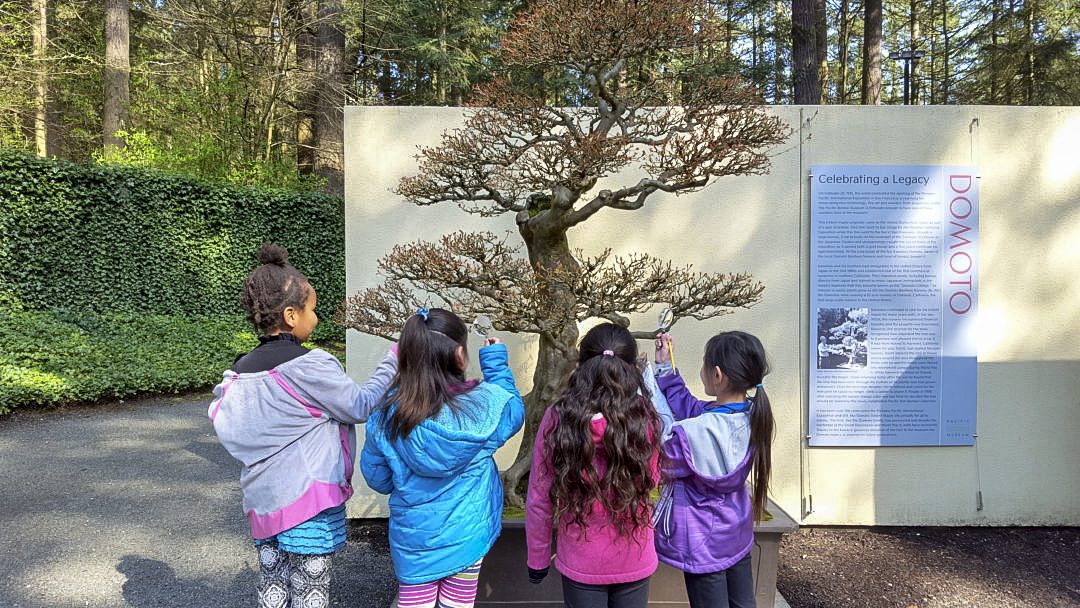

Pruning the maple required Toichi to climb a ladder and, in his 80s, he was no longer able to do so. He sent the tree on long-term loan to a new bonsai museum near Seattle in 1989.

Museum curators carefully studied the tree to prepare it for public display. They flushed out the trunk and found snail shells, gravel and walnut shells, the leavings of the Domoto children. The tree had experienced trauma in its life. At one point the top had been cut off, leaving a bare spot. It was decided to style the tree in keeping with time-honored bonsai practices.

Story of resilience

Toichi passed away at age 98 in 2001 and his children, Marilyn and Douglas, officially donated the heirloom tree in 2015 to the newly-renamed Pacific Bonsai Museum in Federal Way.

“We feel very deeply about the maple,” says museum curator Aarin Packard. “We held a ceremony when it was donated permanently. Its story of resilience touches our visitors.”

The Domoto Trident Maple in three seasons over the decades

The maple evokes an air of pleasure that Kanetaro and Toichi surely experienced as they worked on it. The bark is elephant gray, with a taut, papery skin. Thanks to the devotion of three generations of a family that, like the tree, has ancestral roots in Japan, it is now enjoyed by tens of thousands of visitors every year.

It has become the museum’s signature tree and when it came time to name it, the curators didn’t hold a formal discussion, Packard said. The tree just naturally came to be called the Domoto Maple. It’s the only one in the collection with a family name, he said.

Photo courtesy Pacific Bonsai Museum.

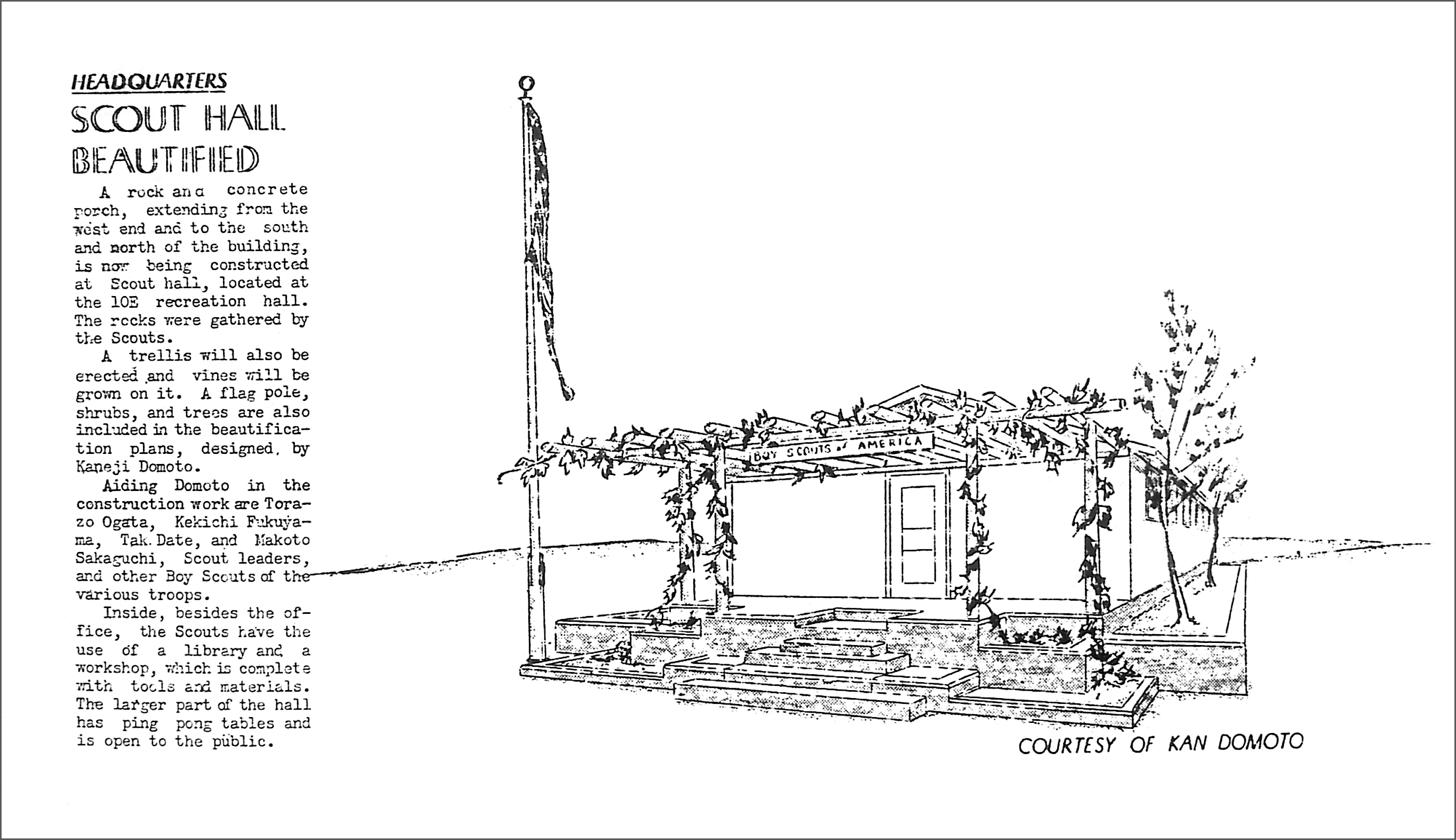

Two Domoto redwoods, separated early

Soil-planted in Hayward, California

In the late 1950s, Toichi Domoto acquired several three-year-old coast redwoods (sequoia sempervirens) as stock material. One was planted in the ground in Hayward, California, where Toichi ran his wholesale nursery business. It grew to a towering height.

A sibling in Washington

Toichi selected another of the redwoods to train as a bonsai. Beginning in 1957, he styled it for nearly 30 years. It was donated to the Pacfic Bonsai Museum and is one of the oldest examples of a redwood trained as a bonsai, according to Aarin Packard, the museum’s curator.

The outline of the bonsai is seen here in a winter enclosure. The pair of redwoods, separated at a young age, became a controlled experiment of sorts. It leads one to ponder whether that is what Toichi intended when he set the trees on their divergent paths. In a 1976 filmed interview, he points to a small cedar bonsai in his garden and then gestures to a grove of giant cedars behind him, saying, “You’d never think it was the same thing as those big trees back there.” (Video below, 12:25)

Top photo courtesy of Pacific Bonsai Museum. Bottom photo, 2019, courtesy of Jeff Stottlemyre.

'Do you still sell plants at the old price?'

Toichi Domoto video interview, 1976. At 8:31, describes an old customer who found an 1890 nursery receipt for imported camellias from Japan. price: 50 cents. Maple bonsai: 9:55. At 12:08 shows cedar bonsai compared to cedar tree in ground. Courtesy of Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, via Internet Archive. Copyright Steven Fisher.

Credits

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: courtesy of Domoto family, Pacific Bonsai Museum, Internet Archive

Special thanks to:

Marilyn Domoto Webb, Alix Webb, Peter Domoto, Pacific Bonsai Museum, Aarin Packard, Kathy McCabe, Gary Kawaguchi, Dennis Makishima, Lynnette Widder, Thad Russell, Jeff Stottlemyre, Densho.

Supported in part by The National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program