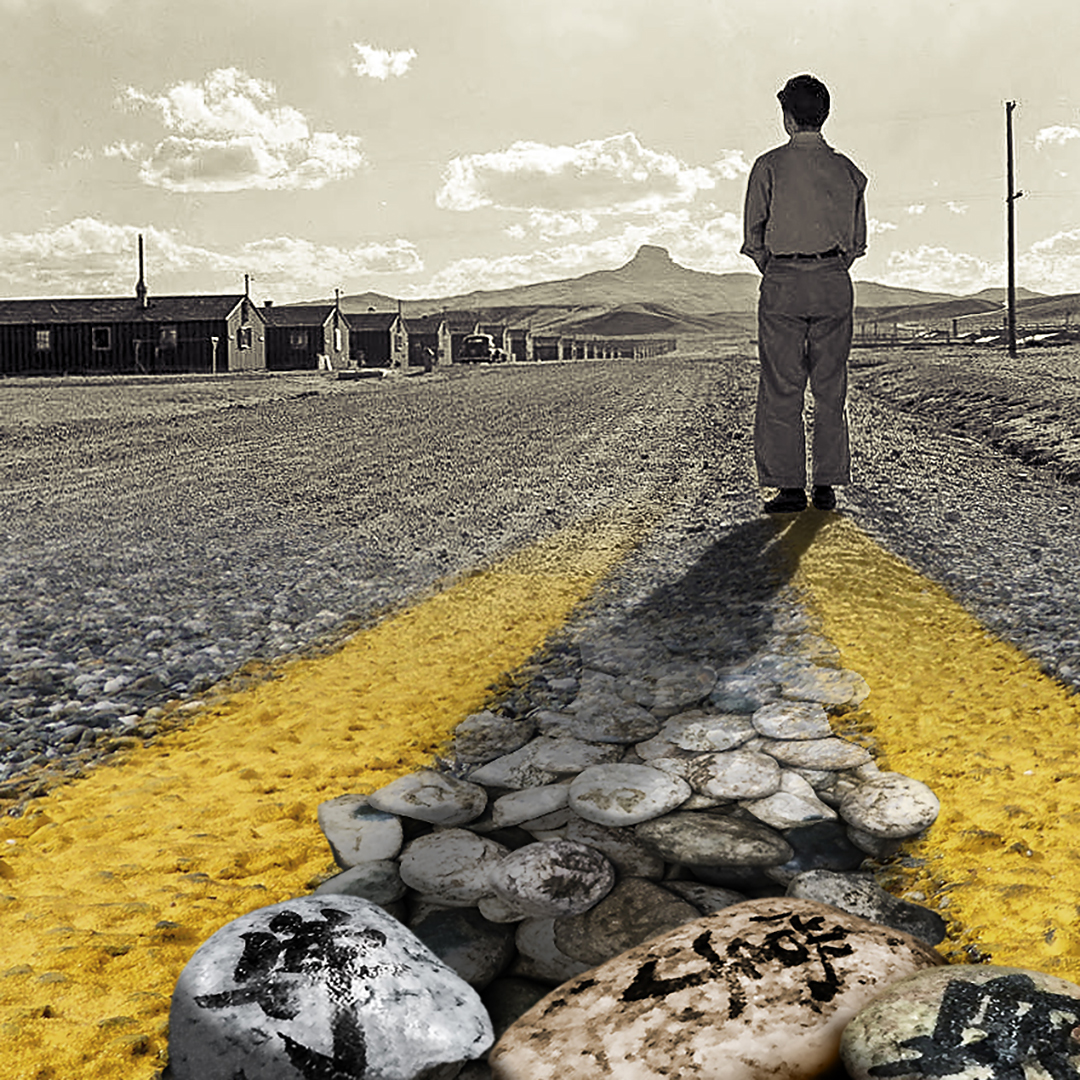

This is a story that begins and ends far beyond the barbed wire fences of the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming. It’s a story that stretches all the way from thirteenth-century Japan right up to the present; a mystery that remained unsolved for over 50 years. It may also be the story of one man’s act of unshakable faith during one of the darkest periods of his life.

After the Heart Mountain camp closed in 1945, the Bureau of Reclamation opened the area up to homesteaders, giving away parcels of land through a lottery.

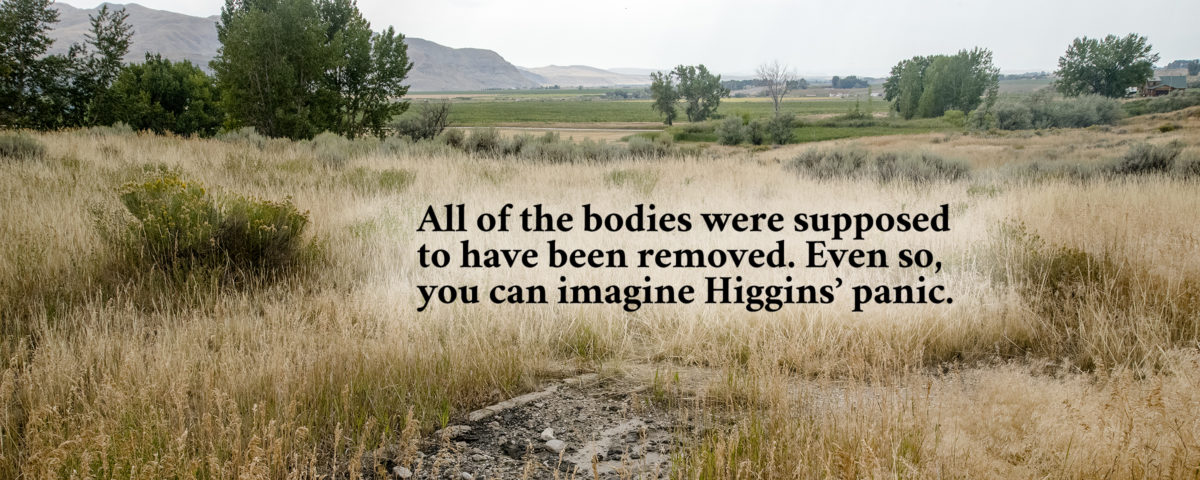

The Bureau began to raze the ruins of the camp, preparing the land to be given away. While clearing the old cemetery area with a grader, heavy-equipment operator Bill Higgins hit something underground. All of the bodies were supposed to have been removed. Even so, you can imagine Higgins’ panic. He cut his engine and climbed down to inspect. He discovered not a casket, but a 55-gallon metal drum buried just under the surface. Its top had been sheared off by his blade. Peering inside, he saw that the barrel was full of pebbles, more than 1,000 of them. Stranger still, each pebble had a single Japanese character painted on it.1

Higgins notified Les and Nora Bovee, who had been awarded the land the barrel was buried on. Les had spent the war as an airplane mechanic in Italy. He had recently returned to his native Powell, where he met and married schoolteacher Nora. The Bovees set out with shovels to excavate the barrel, which was still about two thirds intact. 3

Les placed the barrel of stones in his barn. He frequently showed it to friends and historians, in the hope that someone might be able to tell him what the stones were, or who had made them. As years went by, Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated at Heart Mountain began making pilgrimages back to the site of the former camp. Word spread among the pilgrims of the Bovees’ mystery stones.

Nora asked the wife of one former incarceree to translate some of the characters for her. She mounted the stones and translations to a board, which hung on a wall of her ceramics shop — itself a former Heart Mountain barracks — for nearly 35 years.4

Despite all the attention, no one could give the Bovees any history of the stones. The stones still remained a mystery in 1994, when the Bovees donated what remained of them—656 pebbles—to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.5

It was at the museum, some years later, that the mystery stones caught the eye of Japanese scholar Dr. Sodo Mori. Mori, an expert in Buddhist history, had a hunch as to what they might be. He knew there was a long tradition in Japan, dating back to medieval times, of copying and burying Buddhist scriptures, or sutras. The idea was to preserve the sutras until the Maitreya Buddha, the future Buddha, came to Earth to show humankind the way to enlightenment. In the 1600s, burying paper scriptures fell out of fashion, and devout Buddhists instead began copying the sutras, one character at a time, onto pebbles. Then they would bury the whole collection.6

Mori suspected he had found an American version of this “stone scripture” tradition. He reasoned that the text on the rocks had to be a sutra that was widely available and regularly used, since it had been brought into a concentration camp. He narrowed it down to six scriptures: the three Pure Land Scriptures, the Heart Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, and the Hannya Rishukyo.7

Each sect of Buddhism tends to emphasize one of these sutras above the others in their worship. By figuring out which text was used, Mori believed he could narrow down the identity of the stones’ creator. He and his colleagues entered all the legible characters from the stones into a database. Using a computer program written especially for the task, they began to compare the characters to the scriptures. They were looking not just for the presence of each character, but for the frequency it appeared. In the end, they found a match: the first five books of the Lotus Sutra, the sutra favored by the Nichiren sect of Buddhists.13

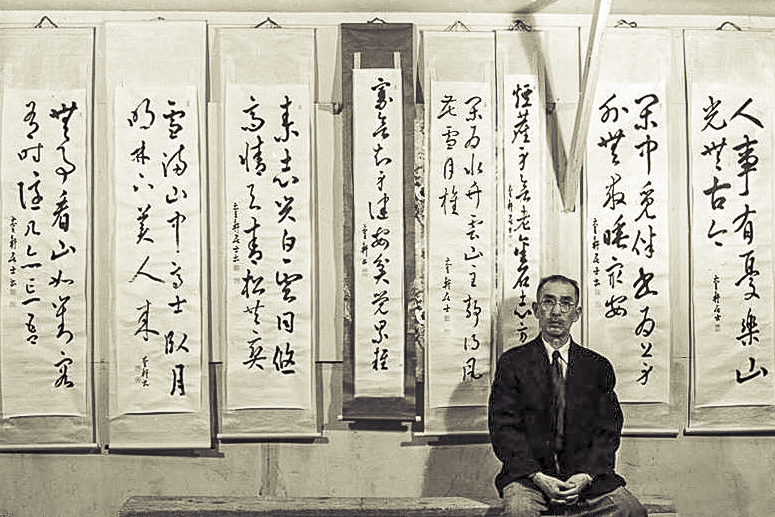

Mori felt certain that the mystery stones’ creator must have been a devout Nichiren, possibly a priest. The brushwork on the stones suggested that the creator had also been trained in Japanese calligraphy. Mori pored through the Japanese editions of the Heart Mountain Sentinel, the camp’s newspaper, until he found a person who met all these criteria: Reverend Nichikan Murakita.14

In 1940, Murakita, a 33-year-old Japanese native from Kagawa-ken, established a Nichiren Temple in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo district. He also began teaching children at the Hollywood Japanese Language School. Many issei enrolled their children in these schools in addition to American public school. It was their attempt to instill traditional Japanese culture and values in their children, even in a foreign land. A distrustful FBI, however, strongly believed — despite having no evidence — that these schools were staffed by agents of the Japanese government. 15

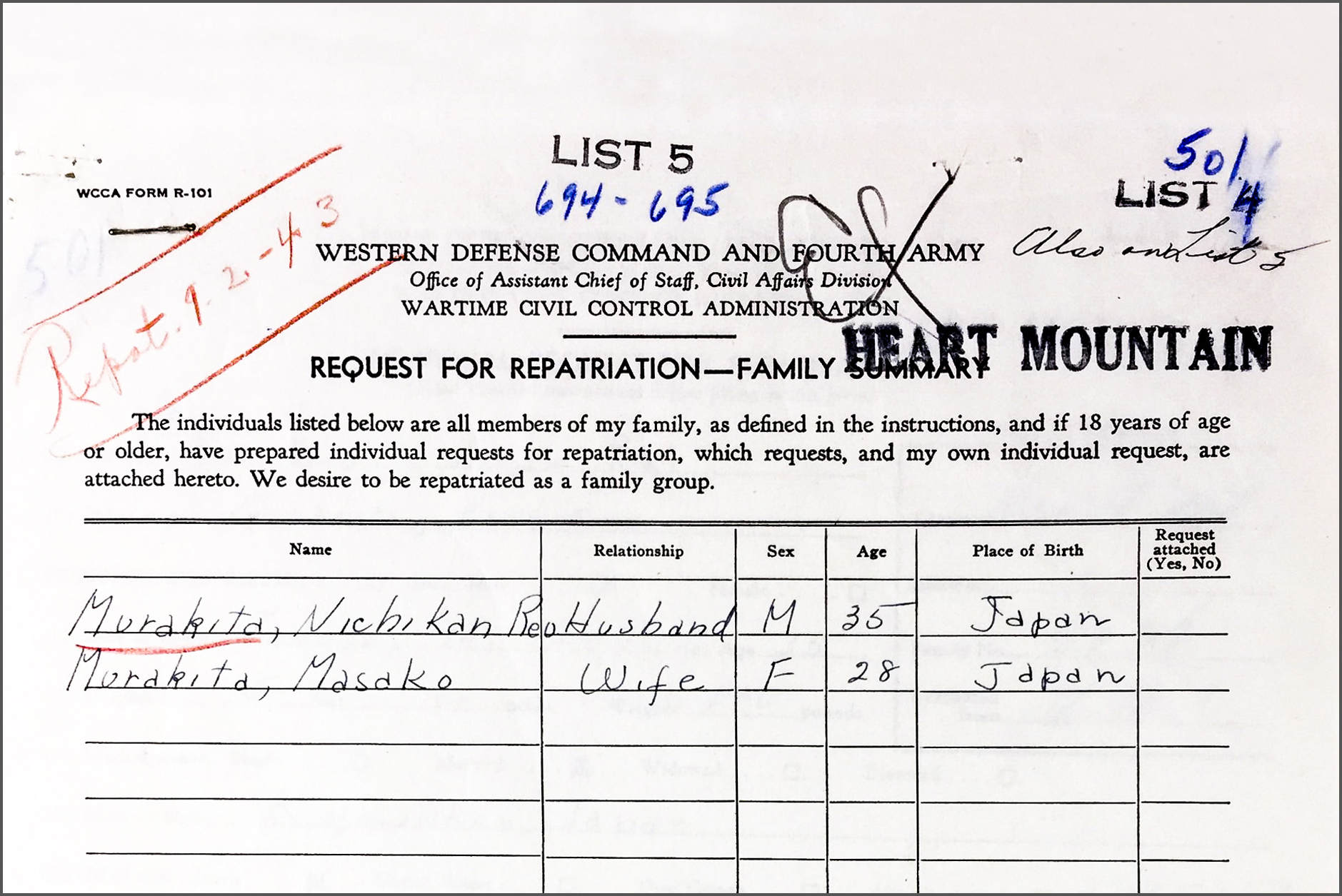

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the FBI executed a mass arrest of some 250 Japanese-language instructors in California on March 13, 1942. The local authorities picked up Murakita that day.19 Murakita likely spent the night in Los Angeles County Jail before being transferred to the Tuna Canyon Detention Station on the outskirts of the city. He was eventually released to join his wife, Masako, at the Santa Anita racetrack, which had hastily been converted into a detention camp for more than 18,000.

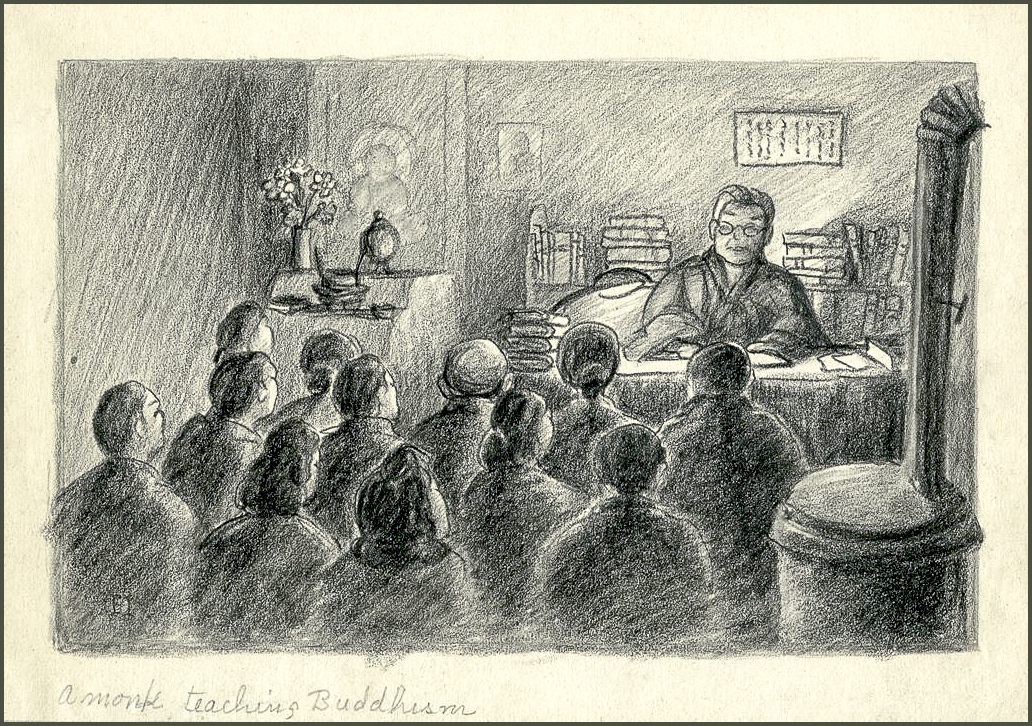

Murakita and Masako were eventually removed to the Heart Mountain camp. He and the other twelve Buddhist priests at Heart Mountain realized that faith communities would now be more vital than ever. They quickly organized a Heart Mountain Buddhist Federation. Murakita, being the only Nichiren priest in camp, represented his sect. A shared Buddhist church space was established in Block 17.

Murakita began conducting regular Nichiren services in camp shortly after his arrival. He also began teaching Japanese calligraphy, a skill he had taught himself, and perhaps began copying the Lotus Sutra. What we don’t know is whether or not his calligraphy classes included the creation of the Heart Mountain sutra stones. Some theorize that the sheer number of stones suggests multiple creators. Others debate whether the brushwork on the stones is from one hand or many. The apparent secrecy in which the project seems to have been carried out suggests that the writing on the stones may have been an act of devotion carried out by Murakita alone, but the absence of confirming evidence leaves behind an aura of mystery.20

By spring 1943, Murakita had stopped holding regular church services. He remained active in the Buddhist Association, and would occasionally give funeral rites, but the Sentinel no longer lists him among the Sunday priests. It’s likely that this coincided with a major decision that Nichikan and Masako had made: to apply for repatriation to Japan.21

The year before, the United States had made an exchange of Japanese nationals trapped in America for some of its own citizens stuck in Japan. The exchanges were supposed to be equal, though, and the U.S. came up short. Struggling to find more people to exchange, the government extended an offer for repatriation to issei in the concentration camps. Discriminatory laws barred the immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens, so they were technically still Japanese nationals.25

Masako had lived in the U.S. since she was 10 and Nichikan Murakita was a more recent émigré, having arrived in 1935. There are many reasons they may have chosen to repatriate. They may have felt mistreated, hurt or angry that their adopted home had betrayed them. Perhaps they simply wanted their freedom back. In the summer of 1943, the Murakitas received word that they were among those approved to return to Japan.27

That August, their neighbors in Block 7 held a going-away tea for Nichikan and Masako, complete with speeches. The couple was to depart on the 24th for Fort Missoula, Montana, where they would be inspected and processed before being sent to New Jersey, to board the M.S. Gripsholm.

Before he left Heart Mountain, Mori believes that Murakita would have taken the stone scripture, placed the pebbles in a metal drum, and quietly buried them in the camp cemetery. The research later done by Mori suggests that Murakita had completed at least five of the eight books of the Lotus Sutra before he had to leave his work behind.28

It’s not known whether Murakita ever again spoke of the stone scripture or his time at Heart Mountain. He died in Japan in 1983, having attained the second highest rank of his sect of Buddhism.29 The scripture, meant to stay buried until the future Buddha came, was uncovered prematurely. We still haven’t attained enlightenment. But if we can learn our lesson from the story of Nichikan Murakita — and the stories of the 14,000 other Japanese Americans unjustly held at Heart Mountain — we might bring ourselves one step closer.30

by Dakota Russell

Heart Mountain Interpretive Center, executive director

Dakota Russell is Executive Director of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation. Prior to moving to Wyoming, Russell spent many years with Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites, helping to preserve and interpret frontier log houses, Native American village sites, Civil War battlefields, and more. Russell believes that history benefits from a plurality of voices, and has worked to ensure that untold stories and all voices are better represented in the cultural landscape.” This is the link to Dakota’s full essay:

http://heartmountain.org/newsletter_16_3718344080.pdf

| The Heart Mountain Mystery Stones | |

|---|---|

| dimensions | various sizes, range app. one to two inches |

| material | granite or granodiorite, some with quartzite |

| date | c 1942-1943 |

| creator | believed to be Reverend Nichikan Murakita with possible assistance from others |

| excavated | site of former Heart Mountain cemetery, 1956 |

| photo | Chizu Omori holds sutra stones uncovered on the Bovees' property |

Credits

The Heart Mountain Mystery Stones by Dakota Russell

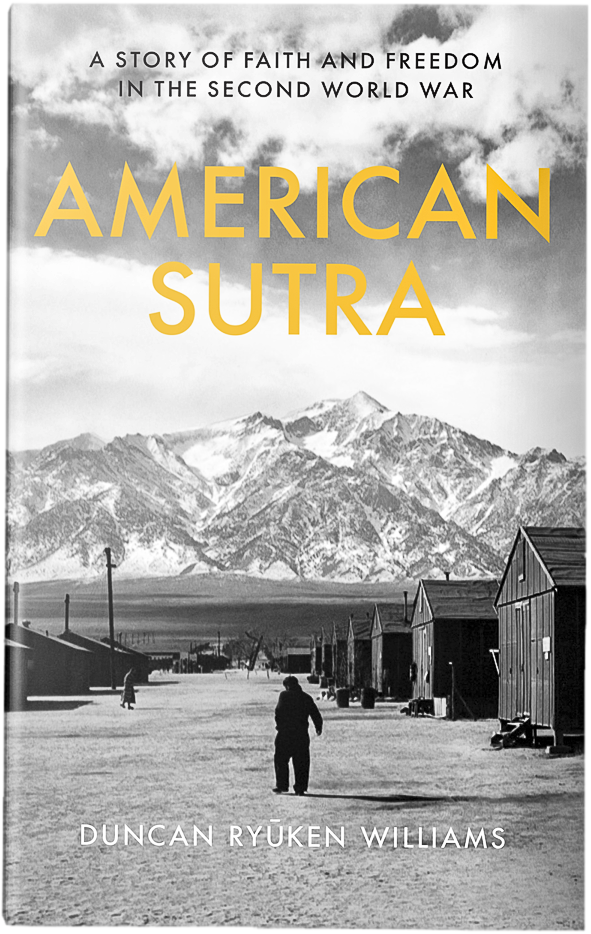

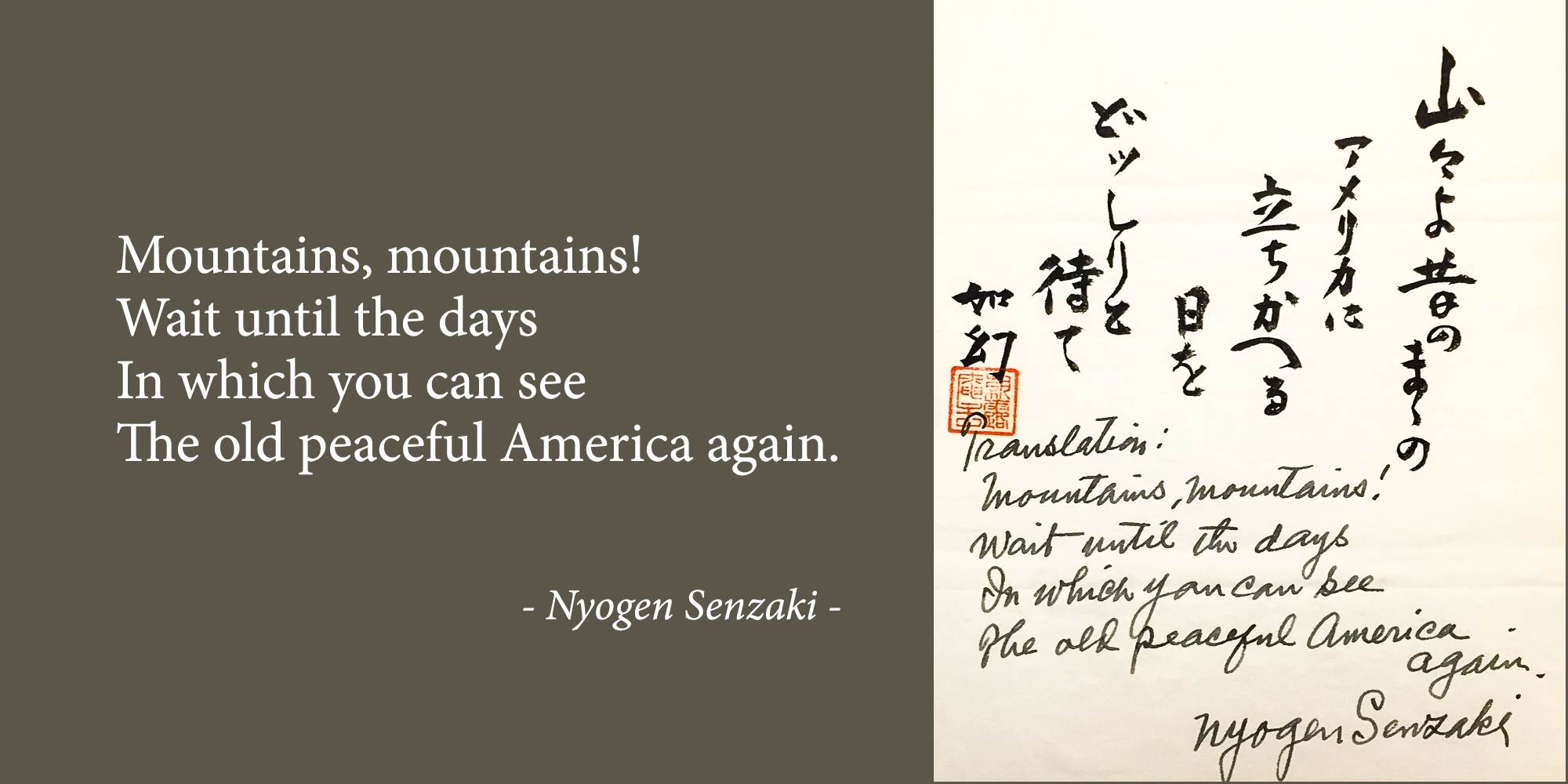

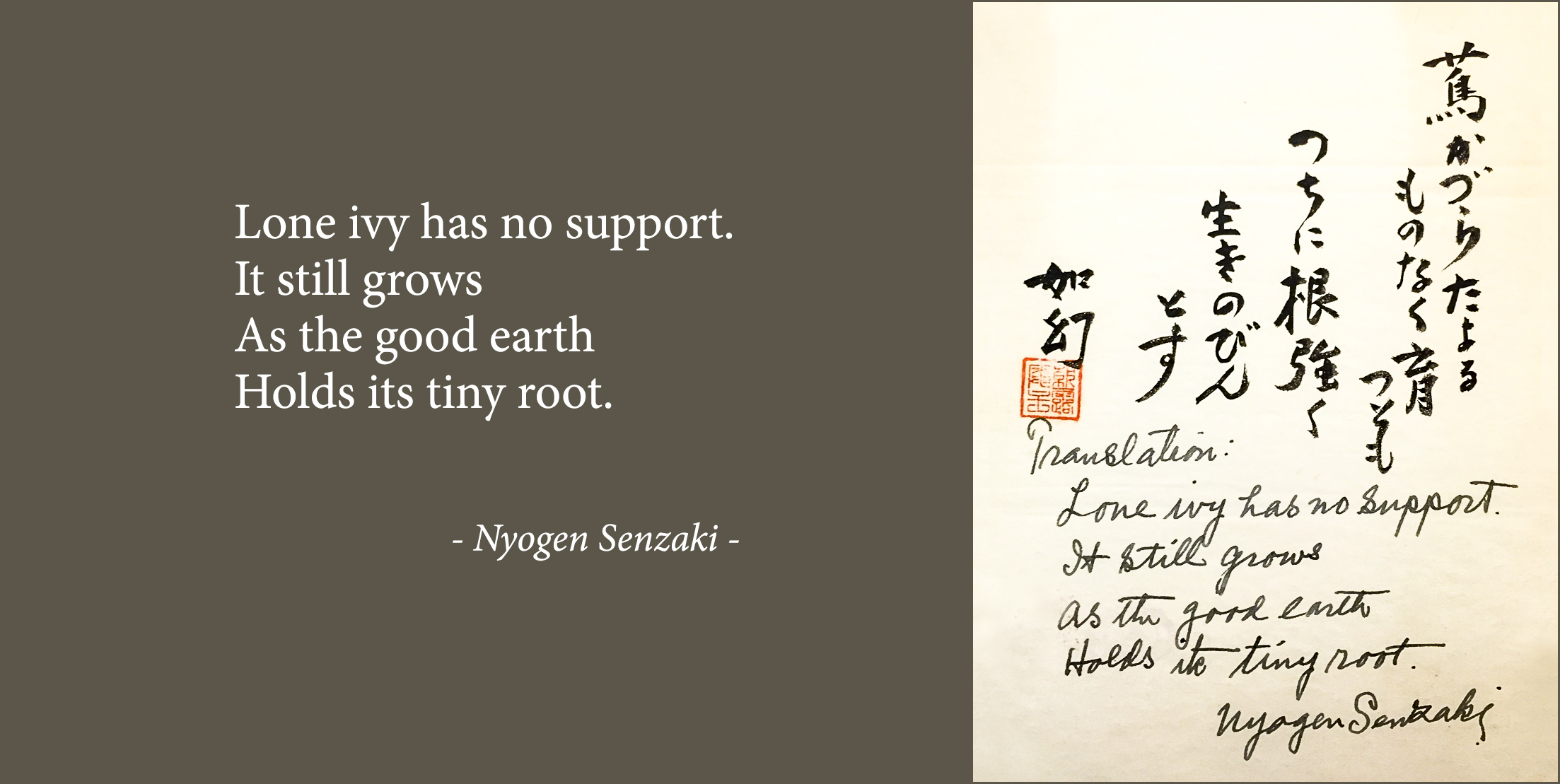

The American Sutra of Nyogen Senzaki by Nancy Ukai

American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War by Duncan Ryūken Williams

editorial: Nancy Ukai, art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: Stones – Nancy Ukai 2017, Lotus Sutra scroll 12th century Japan – Wikimedia Commons, Lotus – David Izu 2007, Heart Mountain landscape – David Izu 2018

Special thanks to:

Dakota Russell, Duncan Ryūken Williams, Patti Hirahara, Mark O’English, George and Frank C. Hirahara Collection, Washington State University Libraries, Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Professor Karl Lillquist, Professor Michael Manga, Toby Bonner, Dan Cogger, Powell Tribune (Wyoming), Ruth Pfaff, Chizu Omori, Emiko Omori

Supported in part by The National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program