In 1933, Takato Hamai suffered a left hip infection that put him in and out of surgery, in a plaster cast and made the 35-year-old bedridden for years in San Francisco. An operation shortened the leg by an inch-and-a-half. In 1941, he had finally healed when a car accident broke his femur in the same leg.

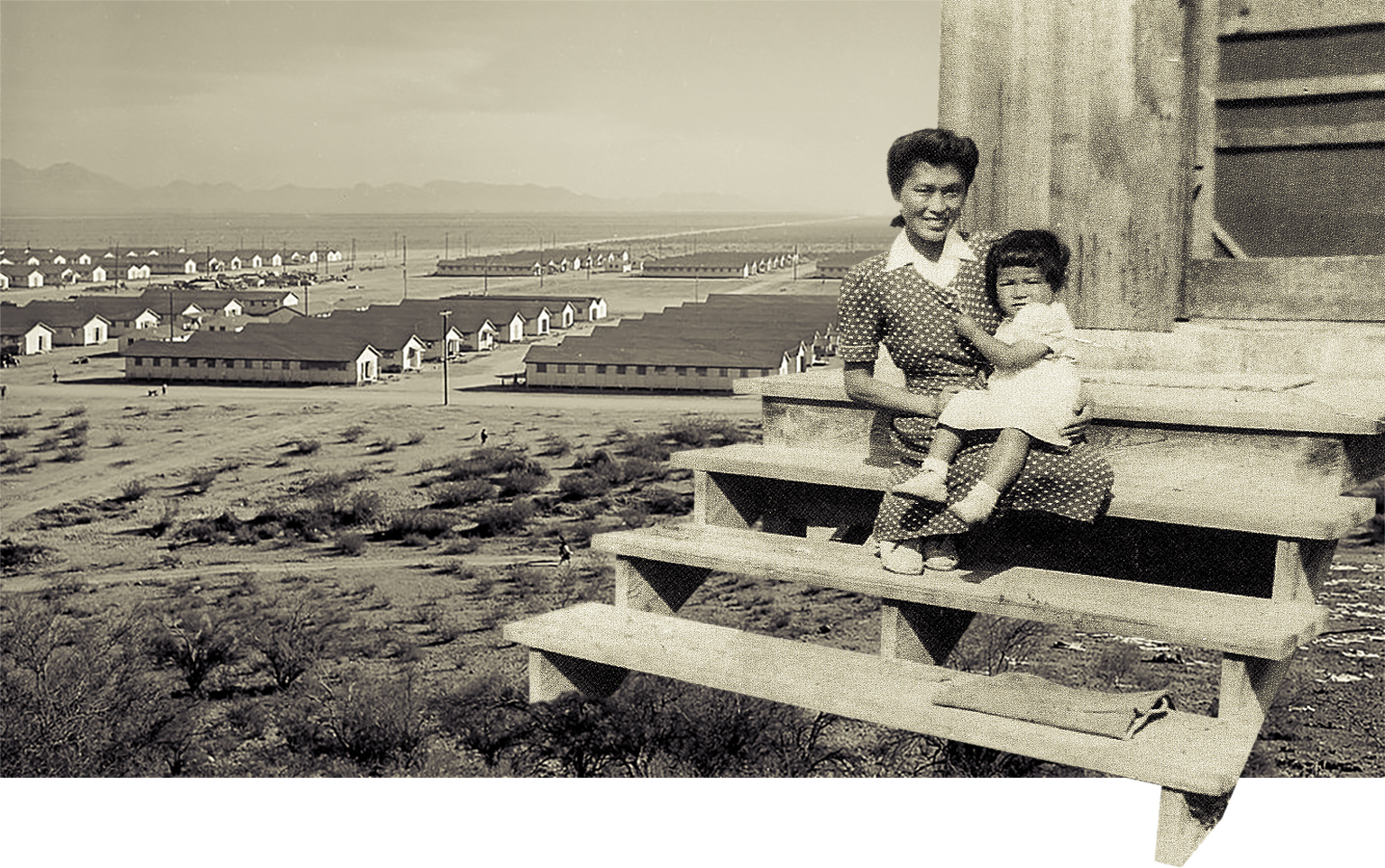

In the summer of 1942, Takato was shipped to the Canal unit of the Gila River concentration camp in Arizona with wife Yukiko and their three young children.

Since his leg problem existed before camp, it’s an open question as to why Takato needed to make his own crutches there. But Ken Hamai, a son, said that his father told him that he had to make them and “used steam from the ofuro to bend the wood,” presumably in the communal bathing facilities shared by 200 people in Block 10. Mismatched nails and small metal washers bound the hand grips.

Takato was an immigrant and in his native Japanese, crutches are called matsubazue or “pine needle sticks” (松葉杖). The ends of Takato’s — the wood carefully split to near the breaking point — visually recall their namesake. The underarm supports also suggest a Japanese sensibility, their lines evoking Japanese temple roof joinery or shrine gates.

The crutches were light, comfortable for Takato’s 5’ 6” height, and sturdy.

The patina and wear marks suggest that the crutches were well-used, but unfortunately there is no background information about them other than the anecdote about how they were made.

Takato wrote poetry, journals and newspaper columns during the war, but the crutches do not appear in his camp writings either.

The Hamai family is left with the presence of an artifact and an absence of narrative, something that is not unusual for wartime artifacts. Objects often survive without their stories.

The children were young during the war and don’t remember the crutches although they have lifelong memories of their mother changing the bandage everyday on their father’s oozing wound. Tak, who was 10 when he entered camp, remembers that his father had trouble negotiating the barrack stairs.

Takato’s diary mentions only in passing the difficulties of getting around on uneven ground. “When I got out of work at 5 o’clock, the roads were very muddy and it was hard to walk,” he wrote on a rainy day in 1943.

It’s not unusual that there isn’t a single photograph showing Takato using crutches. Fifty years before the Americans with Disabilities Act, crutches symbolized the stigma of disability. Even Roosevelt was not photographed using his wheelchair during his presidency.

It also was the case, however, that Takato was genuinely preoccupied with a different sort of mobility: the family’s. When would they be released and where would they go?

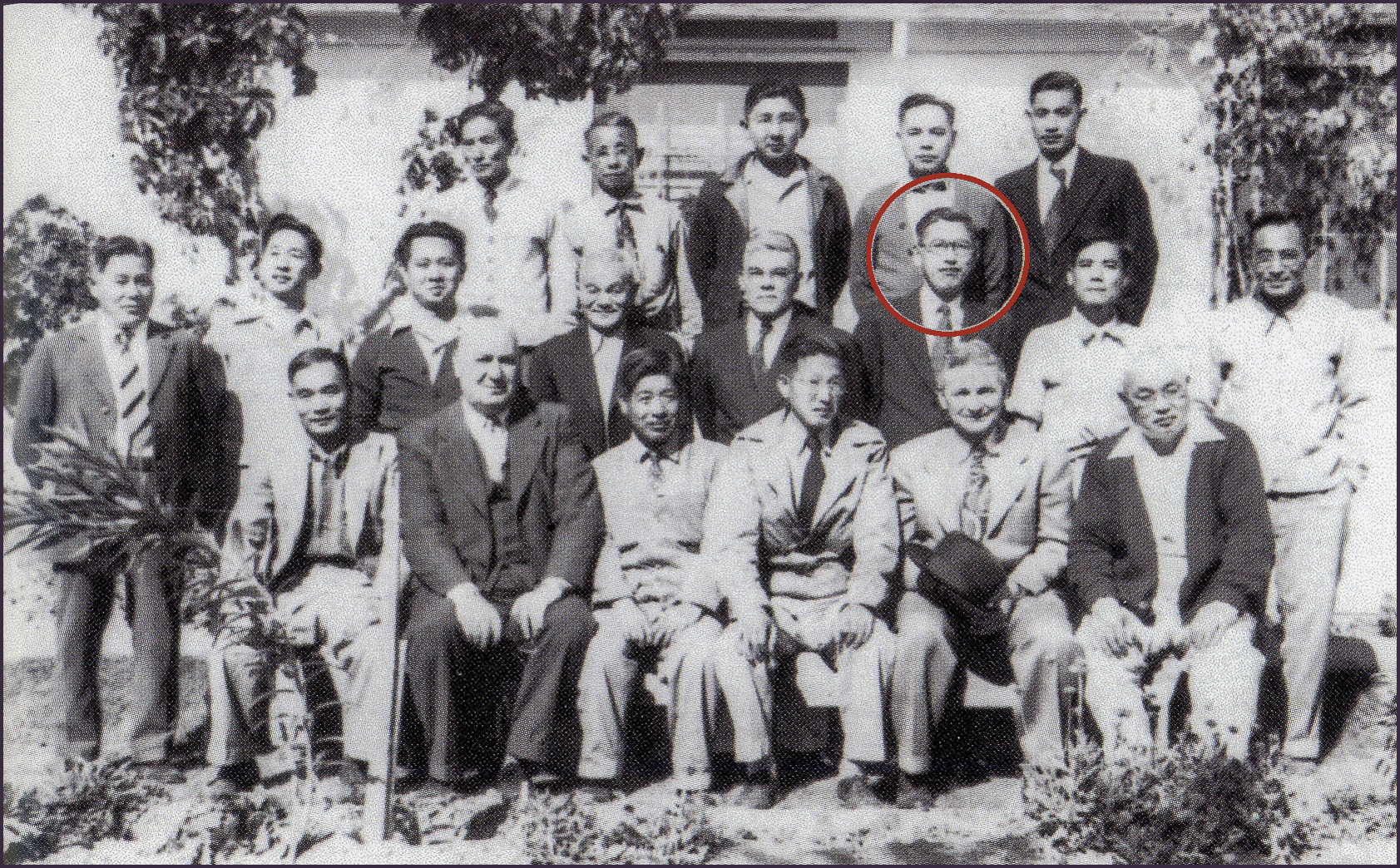

Takato had taken a job as a relocation officer at Gila River and this required him to monitor the outflow of inmates. Such observations dominated his journal entries from 1943-1945. The diaries were written in Japanese and the children had them translated 75 years later.

Takato was born in 1898 near Hiroshima city. His parents had emigrated to the U.S. when he was an infant, leaving him behind with a grandmother. They divorced while he was in Japan, when he was 10. By the time he arrived in Denver, at age 19, he briefly reunited with his father but “essentially he was on his own” and had to become independent, his daughter, Michi, said. He became a “house boy” and did menial labor in exchange for room and board.

Takato moved to California and in 1930, he and Yukiko Alice Kozuki, a nisei born in Stockton, married. The couple were living in San Francisco when the mass roundup of Japanese Americans loomed.

In March 1942, the couple fled with the children to Parlier, near Fresno, to live with Yukiko’s family outside the exclusion zone. But the boundary lines changed and everyone ended up in Gila River.

Shortly after imprisonment, Takato began writing columns in Japanese for the Rocky Shimpō newspaper in Denver.3 He observed the unsettled environment “where immoral behavior occurs: unmarried women getting pregnant, not knowing by whom . . . married men having an affair,” and the fighting in barracks that erupted when people were “forced to live in primitive . . . cramped quarters.”

His poetry found solace in nature but the diaries dwelled on leaving. In the midst of kiln-like heat and icy winters, each person’s departure fed his worries about the future.

The War Relocation Authority’s program to resettle inmates was intended to reduce the camp population and the cost of running an archipelago of prison sites. Inmates were encouraged to resettle outside the West coast if FBI clearance was obtained and a controversial loyalty questionnaire passed. Proof of housing and a job, or admission to a school, was required, .

Single men and couples were taking seasonal leave to top beets. “Mr. and Mrs. Matsumura said tomorrow they are departing for a daikon job in Montana. They said goodbye tonight,” he wrote (April 13, 1943).

The following month, a similar departure led to tragedy. “Mr. Wada, a 72-year-old, has been missing since Saturday” (May 4). Large search parties, one as big as 1,000, looked for him, but the elderly Otomatsu Wada was never seen again. The camp news reported Wada had said “he was going to join his son, Paul Wada, who recently left for work in the Wyoming sugar beet fields.”5

Hundreds of immigrants who had given up on the U.S. decided to return permanently to Japan, many with their U.S.-born children in tow. “A total of 127 people departed Jersey City last night” on the Gripsholm, he noted. A second group was scheduled to leave Gila in a few days, joining leavers from Manzanar and Poston (Aug. 29, 1943). Two colleagues were among those leaving.

Should the family have joined them? Before the war, Takato had worked for a company that imported food from Japan. Maybe that’s why he received “a notice from Washington that . . . my name was on a list of returnees on an exchange ship to Japan so if I wanted to return, I have to apply. Right now, I don’t want to” (June 19, 1943).

By Nov. 4, 1944, a total of 4,400 people out of a population high of 13,348, had left.

The young were being drafted into or enlisting in the military. An astonishing number of resisters to the loyalty questionnaire — some 1,900 — were forcibly segregated into the maximum security Tule Lake concentration camp in California.

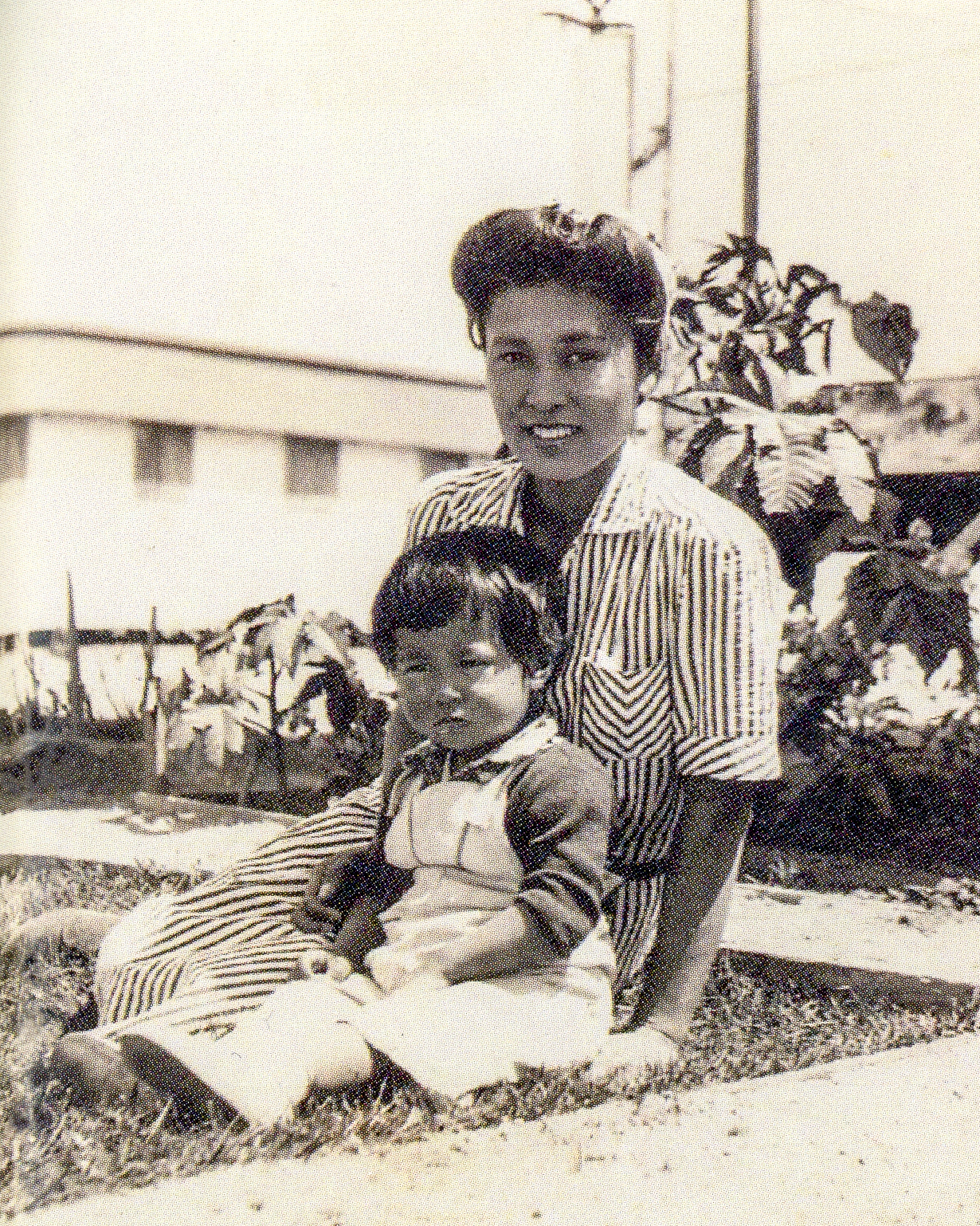

One event added to the population, however. On Sept. 15, 1943, baby Tomio was born to Yukiko and Takato. Eleven days later: “I’m busy washing diapers,” Takato wrote.

When Tomio was four months, Michi, two, was hit on the head with a hammer by Kikuo, the son of a nearby family, which called for a visit to the hospital.

The next month, she contracted scarlet fever. “Two days ago, she had a fever of 103 or 104 degrees, so we couldn’t sleep for two nights,” he worried. Fortunately, her temperature dropped, because a doctor couldn’t make a barrack call (Feb. 26, 1944).

Takato resigned from being chair of the governing Community Council, citing leg problems.7 Working 44 hours a week was taxing. “I calculated my income and expenditures,” he wrote. “The monthly average expenses are $38.47. The monthly income is $36. I’m operating on a $2.47 deficit” (Aug. 31, 1944).

On February 27, 1945, Takato left camp alone to take a job in Denver.

He started to work for the Rocky Shimpō and the family followed six months later. But one snowy winter was enough; the family returned to San Francisco the following year. Takato and some partners formed a food import company in 1948 that became the Japan Food Corp. through a merger. JFC eventually became one of the largest distributors of Asian food in the U.S.

The family moved to the western part of the city, where the children could learn to assimilate more easily into white society than if they had been raised in Japantown. “That was their way of trying to protect us,” Michi said about her parents’ decision. But being called names and made to feel that during the war “our race brought harm to other people” may have created feelings of shyness and hesitancy. “You don’t want to stand out,” Tomio said.

Takato became a U.S. citizen in 1954 and died in 1985 at age 86. Toward the end of his life, he continued to write. He reflected that the years in camp were a prison that “also existed in my mind, which is more difficult to control than one’s body.”

Yukiko lived to be 103. She had run the household and raised six children without a car, packed the household for each move and changed the bandage daily on Takato’s wound for 40 years. In later years, “Mom loved her garden, especially the dahlias, gladiolas and snap dragons,” Michi said. The family created three illustrated family histories, one for their father and two for their mother.

After Yukiko died in 2012, the children found the crutches in a closet. The children chose what they wanted to keep and Ken selected the crutches.

In March, 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic was shutting down San Francisco, Ken decided to donate the crutches. He contacted the National Japanese American Historical Society in Japantown and the executive director, Roslyn Tonai, drove to his home to pick up the crutches and copies of the diaries with mask on and following social-distance protocols. A family artifact that had been created during the lockdown of a vilified race thus began a new chapter, this time as a teaching tool during a different time of confinement.

The interpretation of the crutches continues. Were they secreted from public view out of shame? Or from disuse, as Takato increasingly relied on his cane? Perhaps they were “not the mark of a disability but enabling devices,” suggests Tonai. “Like a good friend, they were his constant companion and kept him going through some tough times.”

* * *

Meet the Hamai children. This Saturday, Oct. 17, the five Hamai siblings will discuss their father’s crutches and the effect that the war had on their family in an online program sponsored by the National Japanese American Historical Society and 50 Objects, from 11 a.m. to noon. Register for the free program here

* * *

Credits

by: Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

banner cover design: David Izu

banner cover images: David Izu, the National Archives, and the Hamai family archives

Special thanks to: Ken Hamai, Michiko Matsuura, Takayuki Hamai, Tomio Hamai, Satoshi Hamai, Bernice Hamai, Henry Matsuura, Yi-Shen Loo, Masako Nakada, Malia Okamura, Neil Burmester, Densho

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service Japanese American Confinement Sites program

This object/story presented in collaboration with the National Japanese American Historical Society