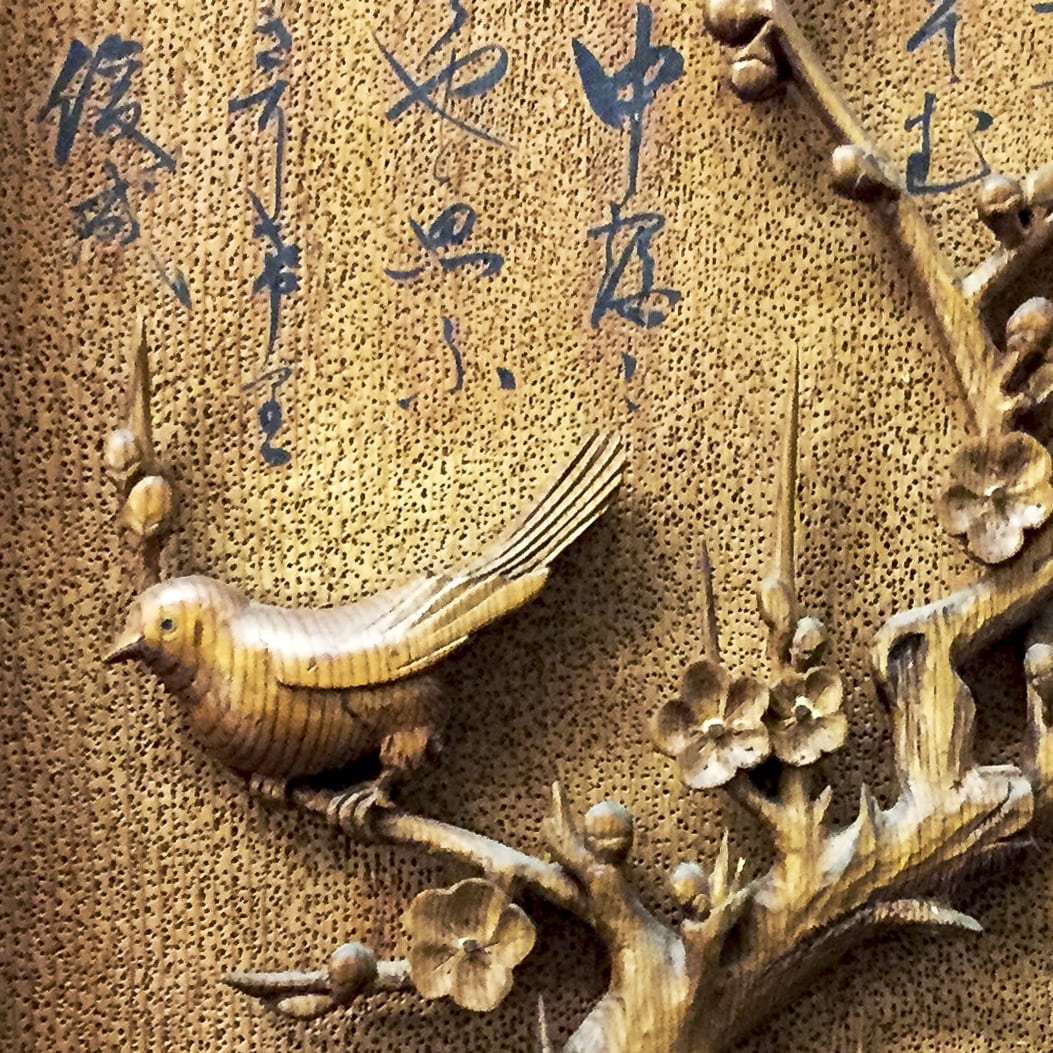

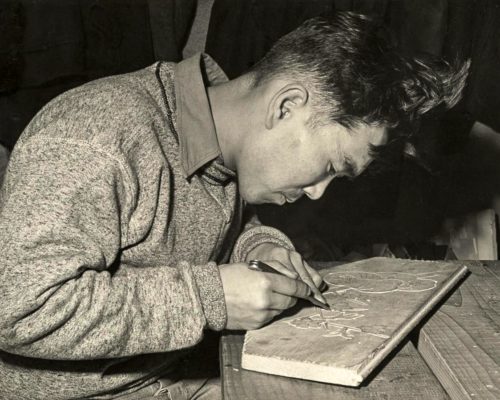

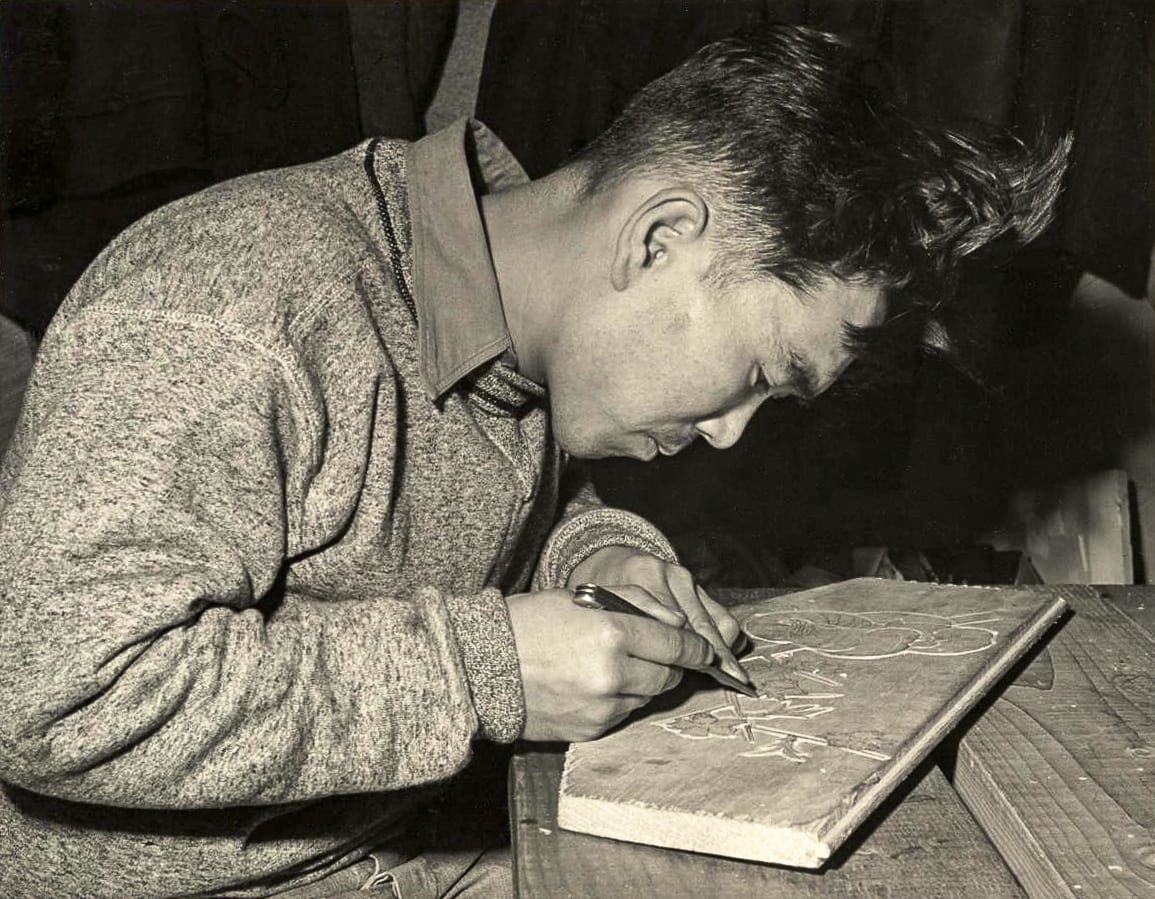

They had never carved before. But the cook in Block 9K, the laundry worker separated from his children, the immigrant apple farmer and two gardeners from California painstakingly chipped away at pine boards until a Japanese symbol of spring came to life: a nightingale in a blossoming plum tree.

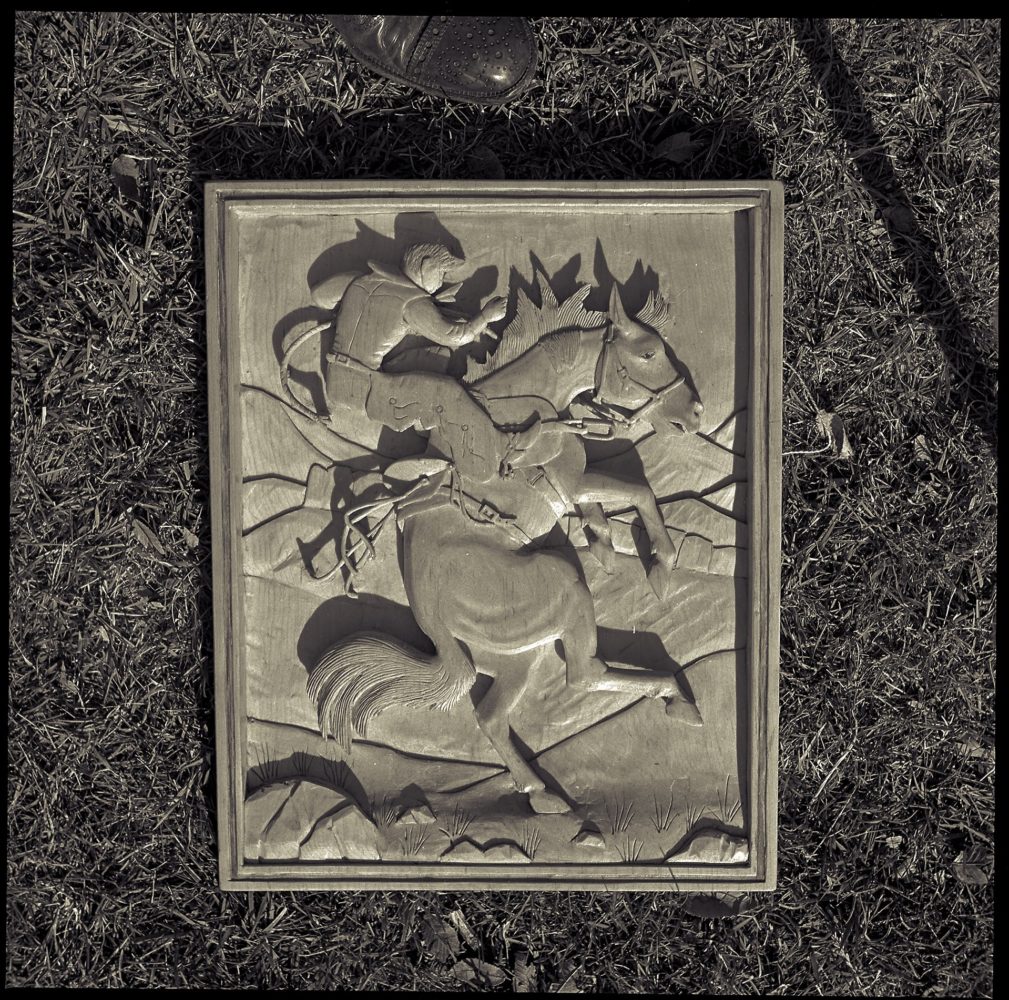

Between 1942 and 1945, while imprisoned on the dusty terrain of southeast Colorado, amateur carvers hatched songbirds on scrap wood from old fruit crates and lumber from the fuel pile.

Inside the Amache concentration camp, they used primitive tools made “from discarded saw blades, worn-down files, automobile springs and other waste metal,”1 wrote crafts scholar Allen H. Eaton.

“A cook from one of the mess halls carved several panels and, borrowing a few more from fellow carvers, used them for decorating the rough interior walls of the dining room,” Eaton wrote.2 He visited Amache in the fall of 1945, before the camp closed, and collected examples with the Japanese themes he so admired.

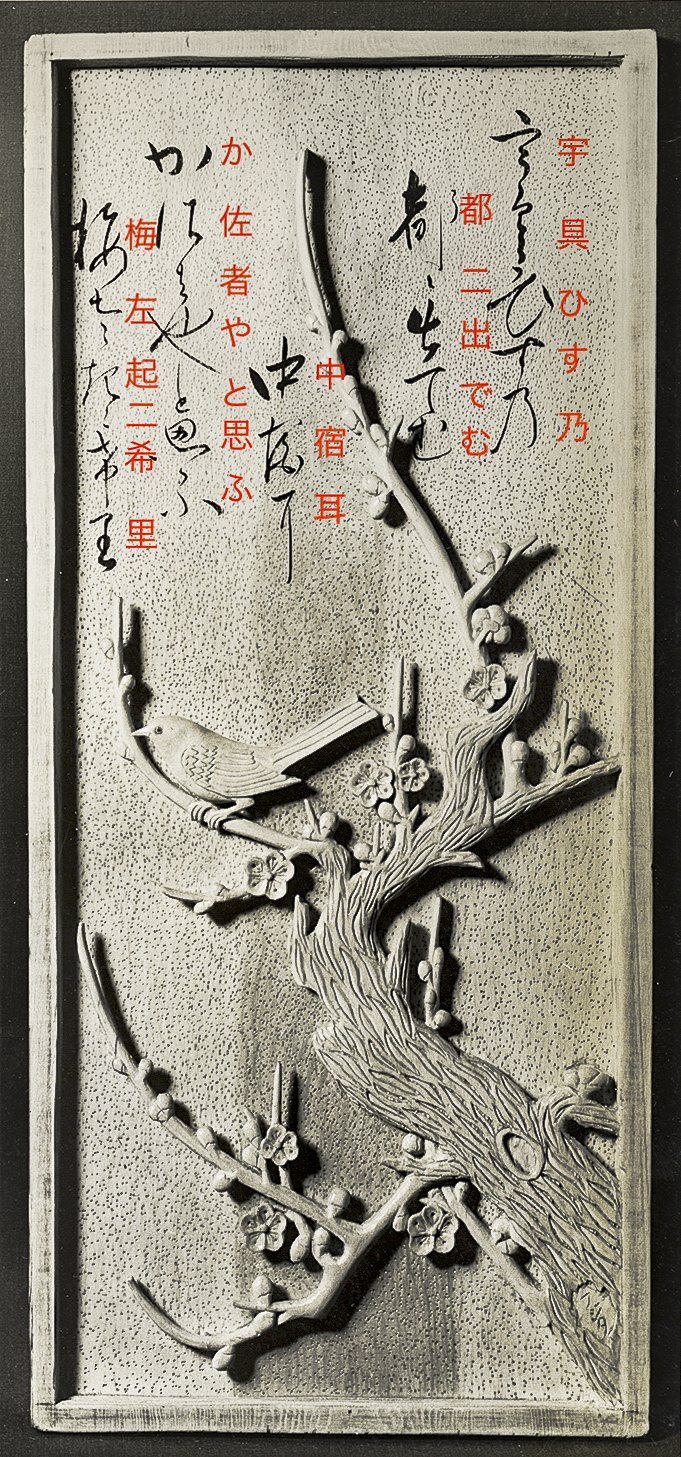

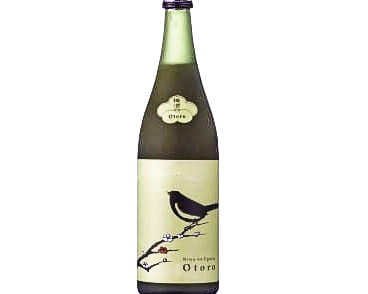

One was a carved panel of a Japanese bush warbler, or nightingale, in a plum tree.5 Eaton took the panels back to New York City, where he worked as a research scholar at the Sage Foundation.

“The best thought and feeling was expended on such traditional themes,” Eaton wrote later.6 What he probably didn’t know was that the calligraphy on the nightingale plaque was a poem that alluded to support for the emperor. Was the carver expressing a political view in artistic code?

Saved by a protest

Seventy years later, in 2015, Eaton’s large collection of Japanese American camp artifacts, which had been held by the Eatons and a contractor’s family in New York and Connecticut, was going to be auctioned. But the sale was suspended at the last minute, stopped by legal action and the outrage of thousands of camp survivors and family members who protested the sale of objects born from racism and unjust imprisonment.

The entire collection of 450 items was eventually acquired by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

Research revealed that a U.S. citizen by the name of Isamu K. Fujita was the carver of the nightingale panel.9 Unexpectedly, this led to a flurry of more warbler sightings.

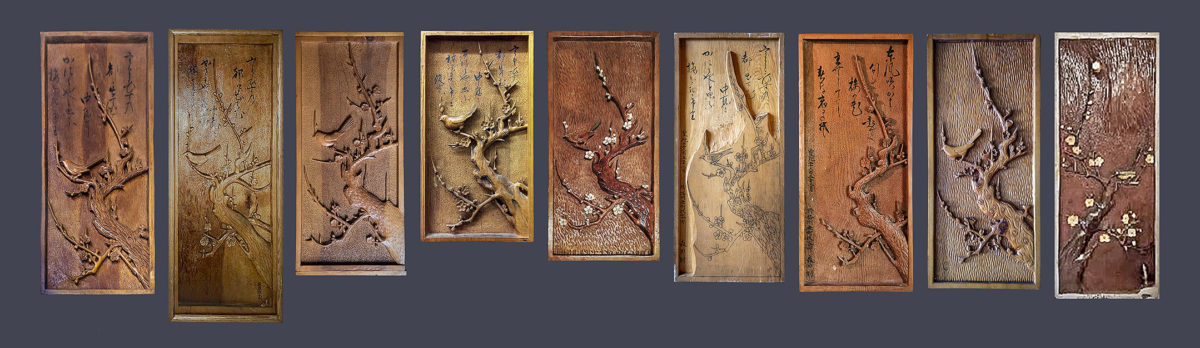

Over the next five years, eight more works with the same theme surfaced in California, Colorado, Oregon and Illinois.

Six were confirmed to have been made at Amache and information about the other three did not exclude the possibility.

That led to questions.

Did the woodworkers know each other and study in the same class? How did beginners learn to carve so well? After the war, what became of the carvers?

The details can’t be fully reassembled because in the intervening decades, memories faded and the carvers died.

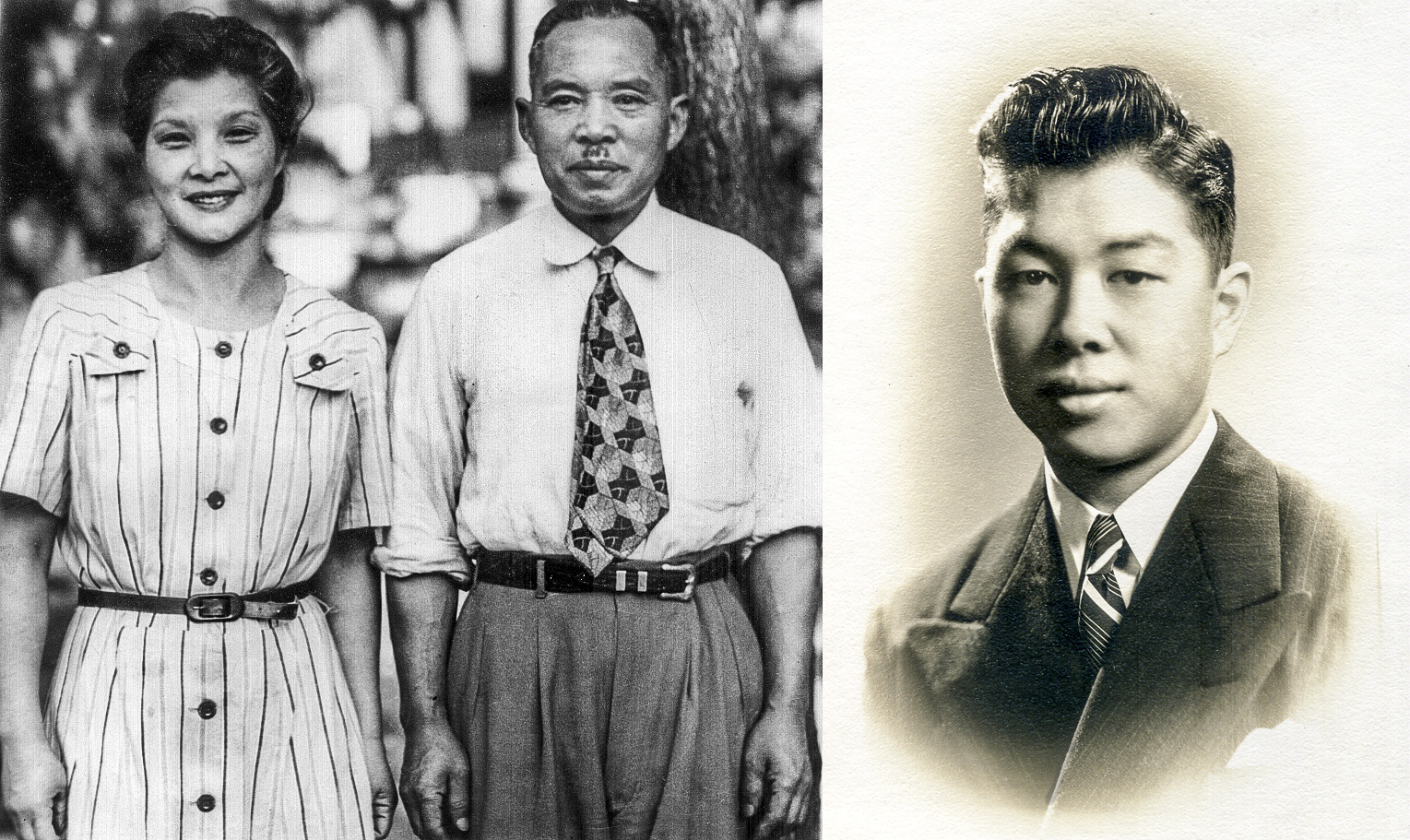

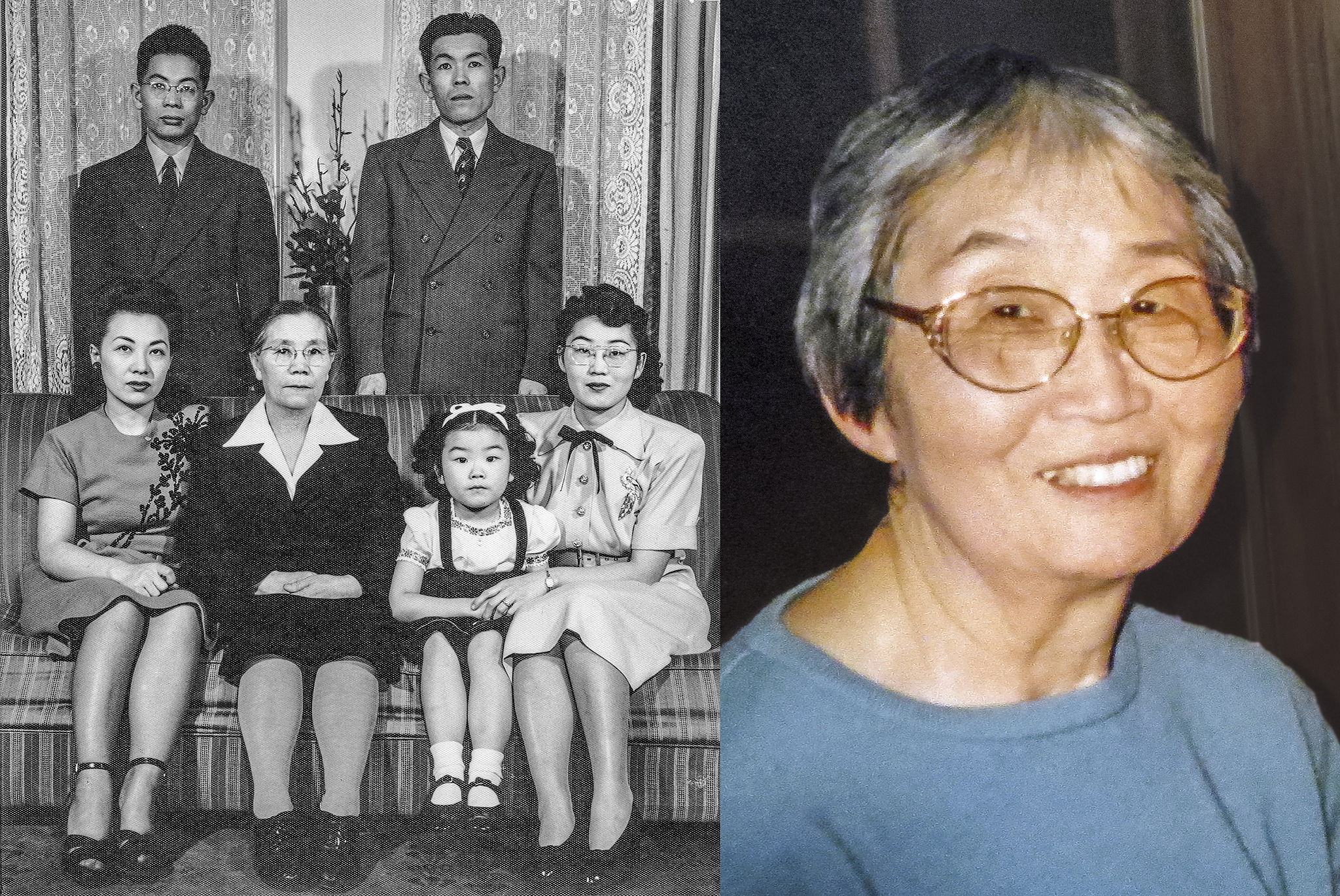

But a portrait of a small society of carvers emerged. Of the five woodworkers who could be identified, all were male and four were immigrants. Fujita was a U.S. citizen educated in Japan, a kibei.

Fujita had been working in 1942 as a gardener in Hollywood and Beverly Hills, California, when he and his wife Masako were taken from their home and imprisoned for the next three and a half years at Santa Anita, California; Jerome, Arkansas; and Amache in Granada, Colorado. A former employer, Alice Erasmus, wrote the War Relocation Authority to vouch for him, saying, “We lost a friend and worker.”11

But his loyalty to the United States was questioned, perhaps because he had spent part of his youth in Japan and a period after that to care for his dying father. A government review board eventually cleared him and the couple was released a year later, on Sept. 18, 1945, the day after Fujita turned 32. Eaton visited Amache around this time but it’s not known how he obtained Fujita’s panel.

Carved during the night shift

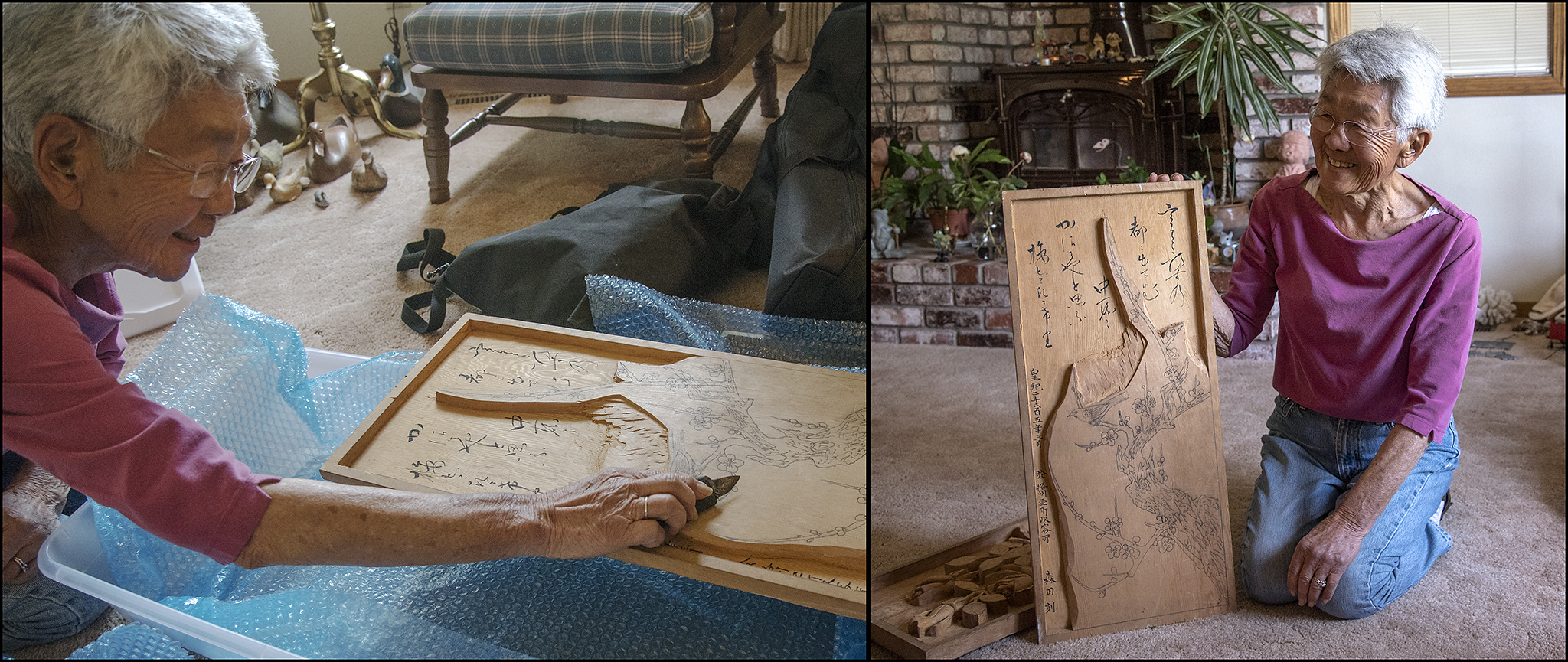

Before the war, Yasutaro Takano was a gardener and president of the Buddhist Temple of Alameda in Alameda, California. He carved two works while confined at Amache 9K-7B, a fish and the nightingale-and-plum theme. “It’s all that we have left from that time,” says his daughter, Cookie, 91, who was incarcerated at age 13.

Cookie remembers the day in 1942 that the family escaped by car from Alameda because “It was President’s Day, February 22,” she said. The evening before, she and her sister, Teruko, were walking to Long’s drugstore to buy cutlery to take to prison camp when they witnessed a Buddhist colleague of Yasutaro’s being taken away in handcuffs by the FBI. “The daughters were crying,” Cookie said. “We ran home.”

At 5:30 a.m. the next day, the family packed some belongings into their ’39 Dodge and drove east to Cortez, in the “free zone.” When the entire state became an exclusion zone for Japanese Americans, the Takanos were moved to the Merced Assembly Center and later to Amache.

Takano carved during the night shift of his job with the camp’s Internal Security police staff, Cookie and her brother, Mas, 88, said. “He was reluctant to work for the camp police,” Cookie recalled, because the officers were viewed with suspicion by inmates, but Yasutaro told the children to rise above the squalor and think of the lotus in Buddhist teachings: “Out of the mud comes beauty.”

Takano sculpted plum branches by undercutting. He made thousands of dotted indentations for the background by tapping nail heads into the pine surface, Mas said, bundling several nails together to press into the wood at one time.

“The process requires time, patience and a steady hand, says Sheri Tharp, a woodcarving teacher of 30 years in Berkeley, California, who examined Yasutaro’s carvings with Cookie. Time was plentiful for the carvers, who endured years of indefinite detention.

Found in a closet

The panels survived because they were carried out of camp, but after that their stories diverge. Two plaques were discovered after the carver died. One hung in a living room. Another was spontaneously given away at Tule Lake, California, by an elderly issei to a stranger who admired it. Another carving was gifted in Chicago.

Two panels by Toshiro Morita, an apple dryer from Sebastopol, California, were discovered in the back of a closet after he died, said Toshie Morita, 88, the daughter-in-law who found them. One panel has no bird. Did Toshiro’s hand slip while he was carving it, leading him to excise it? “There are no mistakes, only design changes,” said instructor Tharp.

Toshiro started a second panel but stopped midway and carried the unfinished work back to Sebastopol. “I didn’t think the woodwork was that special because it wasn’t finished,” Toshie said.

But the partially-carved work shows how Toshiro traced the pattern onto the wood and then began to cut away from the main design. Toshie wanted her sons to complete it, but they never had the time. Now the unfinished panel will be preserved by Toshiro’s grandchildren as testament to his life and its disruptions.

Message in a poem

Four of the nine panels bear the same poem brushed onto the surface. A fifth panel carries a different verse.

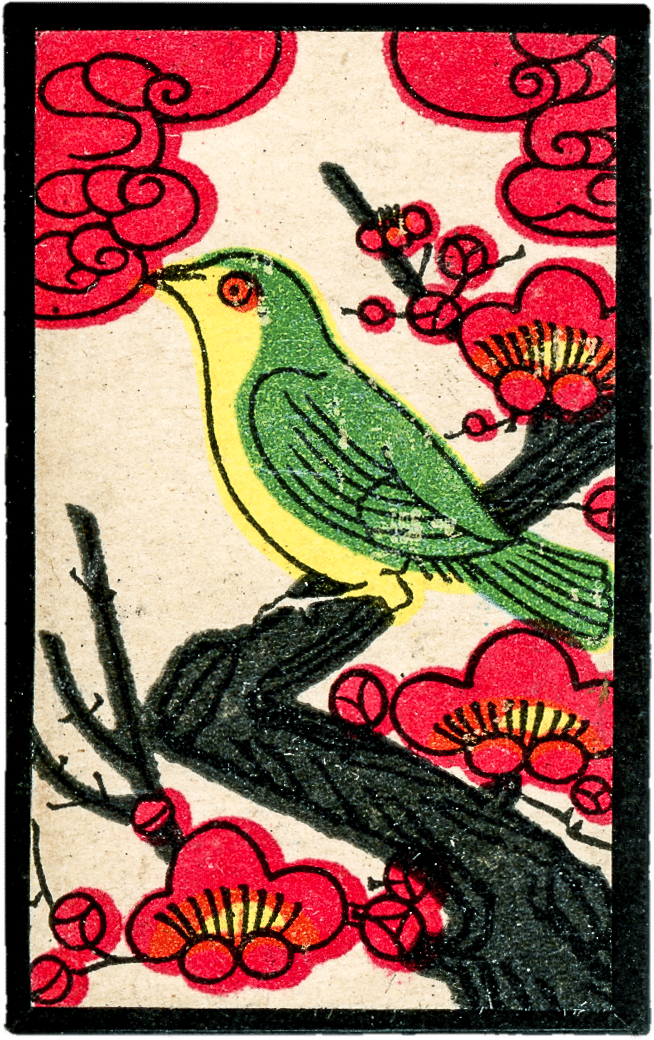

According to research by Ichiro Hanami, retired assistant professor of Japanese language and literature at The George Washington University, the verse that appears on four panels was originally written by the nun Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875).

Otagaki was an artisan, artist and poet. “She also was known as a loyalist of the emperor, a supporter of the sonno joi movement that called for the restoration of the emperor as the ruler of Japan and the ousting of the Tokugawa shogunate,” says Hanami, although she apparently never confirmed nor denied her position.

The poem tells of a bush warbler, or nightingale, leaving the capital during the spring. A blossoming plum tree beckons it to alight on a branch.

うぐいすの都にいでん中やどにかさばやと思ふ梅咲にけリ

Otagaki may have been gently calling for the nightingale (the emperor), as it leaves the capital (Kyoto), to stop by on her branch of blossoming plums as it travels toward Edo, the soon-to-be new capital.

“The warbler and plum blossoms (uguisu ni ume) are harbingers of spring and have been associated in every medium throughout Japanese art history, from Heian period poems to Edo woodblock prints to even one of the cards in the deck of Hanafuda cards,” Hanami says. “As such, there is very little in terms of originality” in this theme.

But the combination of the plum and nightingale with this particular poem may be telling. Could this be a subtle indication of support for Japan and the emperor during World War II?” asks Hanami, who researched and translated the poem for the Japanese American National Museum.

If this relatively obscure poem were a form of coded resistance by Japanese immigrants, it would go unnoticed by censors. In fact, it would not even be understood by the woodworkers’ own U.S.-born children. It’s intriguing that Otagaki veiled her message within a poem. The carvers may have done the same, comfortable with ambiguity and using it as a tool of nuanced expression.

Morita’s no-bird panel bears a different poem, written by the ninth-century poet, bureaucrat and Sinologist named Sugawara Michizane who was exiled, Hanami writes.

“This poem directly references Michizane’s feelings of being in exile. I wonder if it is a reflection of how Japanese Americans in camp may have felt: that they were forced into exile as well. It is interesting that the two poems in juxtaposition contrast each other, one a Japanese loyalist, perhaps defiant of his incarceration, the other sad about his current situation in incarceration.”

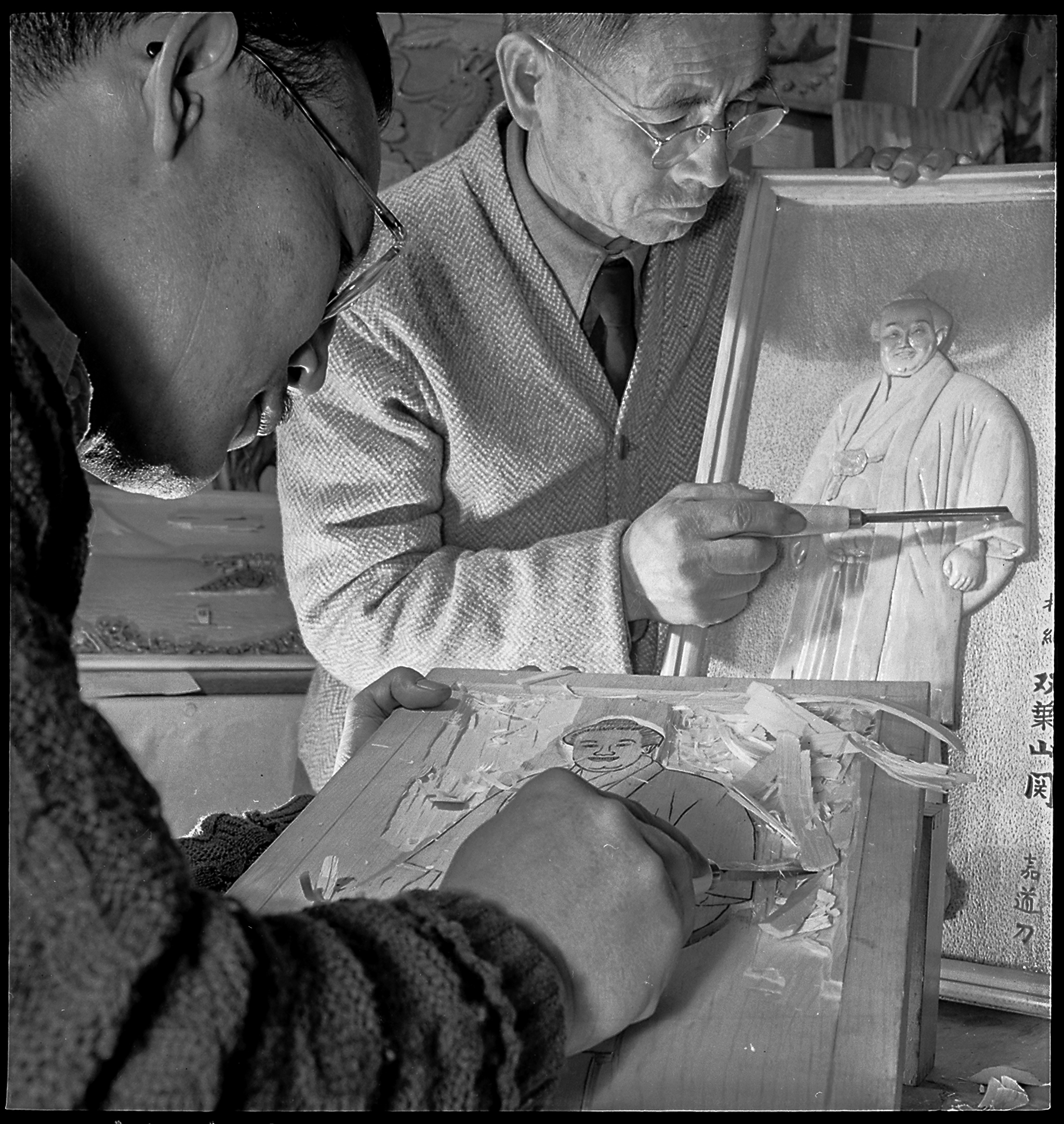

It’s not known who selected the poem but it’s interesting to ponder the possible role of the master woodworking instructor, Yutaka Suzuki, who “taught the craft to more than 20 residents, none of whom had ever studied before,” Eaton wrote.13

Suzuki was born in Fukushima, Japan, and was incarcerated at Amache for three and a half years. Records show that he taught wood carving for adult classes in the 8H school block. He also judged carving events for the Boy Scouts and other programs. He was probably the main (if not only) carving instructor at Amache.

Suzuki offered a pen and brush calligraphy class shortly after arriving at Amache.15 The Otagaki poem is written in what appears to be the same hand on four panels, giving rise to the possibility that Suzuki did the calligraphy and perhaps even selected the poem.

He was a gardener and nursery operator in Los Angeles before being rounded up with wife Masa and youngest son Robert. Their two older sons served in WWII. Suzuki naturalized in Chicago on Dec. 21, 1954. In his petition, he listed his occupation as “woodworker.”

Perhaps more panels will emerge in the future. They are expressions of displacement, captivity and loss, not “Asian decorative art,” as the Rago auction catalogue described them. Nor was Greenwich, Connecticut, their true provenance.17

After their release, none of the Amache woodworkers, with the exception of Fujita, carved again, family members said.

Courage of ancestors

Jintaro Ando made numerous carvings while incarcerated with spouse Itsue in barrack 8G-5F. They had left behind their laundry business in Mill Valley, California, and were separated from their children. A daughter, Hideko, was in Japan, and their son, Toshio, escaped incarceration in Denver. On the outside, Toshio tried to trace their belongings that had been stolen and occasionally was able to see his parents when they received permission to visit him during their nearly four years of imprisonment.

Jintaro hung the carving in the couple’s San Francisco apartment after the war.

The carving eventually was donated to the Amache Museum via Michi Yasui Ando, the couple’s daughter-in-law and sister of civil rights champion Min Yasui. Yasui had intentionally violated the military curfew on March 28, 1942, to test its constitutionality in a case that went to the Supreme Court where his conviction was upheld. That date was designated Min Yasui Day in perpetuity by the state legislature in 2016, the centennial of his birth, and he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama.

Michi, who had her own courageous escape story during the war,19 and family members Hideko Ando and Chihoko Ando, entrusted Bob Fuchigami,20 who had been incarcerated at Amache when he was eleven, to take the panel to the Amache Museum in Granada.

The museum recently moved the carving and the entire collection to a larger building. The Amache camp property, two miles away, is being studied as a potential new federal historical site by the National Park Service.

Of the nine panels, the Ando carving is closest in proximity to its place of origin. It is now used to teach Colorado school children about the fragility of democracy and to show that historical evidence can be found even in a carving. It, too, can prompt memory and narrate untold stories.

The nightingale panels were carved in a cage, birthed in a crucible of loss, racial hatred and confinement. Within these carved plaques are the truth of Takano’s words, “Out of the mud comes beauty,” as well as the poignant silence of unsigned panels.

Their existence is due to the fortuitous convergence at Amache of a master teacher and his immigrant students and a kibei who spoke Japanese. They used waste material and discarded metal formed into tools to sculpt a cultural theme that had existed in the ancestral land for centuries. This must have provided a sense of comfort and a way to make meaning and pass the empty hours.

The pairing of the nightingale with poems that suggest exile and quiet support for the emperor become a uniquely Japanese American creation, a diasporic voice in the Colorado desert, just east of Kansas and 50 miles from the site of the Sand Creek Massacre, in which Cheyenne and Arapaho were killed by the U.S. military in an unjustified attack in 1864. The daughter of a murdered chief was named Amache, and her name and its ghosts were ever after attached to the camp.

After the war, the panels scattered with their owners. Rediscovering them after nearly 80 years and piecing together their stories is a communal attempt to understand what had been buried for decades, awaiting a new reading. Carved shavings that woodworkers blew off finished pieces were carried over time to places thousands of miles from where they originated. By attempting to record their migrations, memories drift back through time to visit as a bird’s song, a poem of lament.

The Amache Woodworkers

teacher and students with their panels

Instructor

Instructor Yutaka Suzuki was born 7 May 1882 in Sōma-gun, Fukushima Prefecture. He immigrated to Seattle on 21 March 1907, returning to Japan to marry Masa Otsuki in Fukushima in April 1916. They sailed back together to Seattle 28 June 1916 and there had four sons between 1918 and 1924, moving to Los Angeles by 1930 where Yutaka was employed as a fruit merchant and nursery proprietor. In 1942 he was removed with his wife and youngest son Robert to the Santa Anita Assembly Center. They were sent in September 1942 to the Granada (Amache) concentration camp, 7K-9F. Suzuki was active as a carving instructor, calligrapher and in block activities. Yutaka and Masa left the camp in March 1945 to Chicago, where they naturalized in 1954. Their two older sons enlisted in the Army during the war. Yutaka died in Chicago on 13 April 1958 and was buried in the Graceland Cemetery. Masa died on 24 May 1970 while staying with her sister in Soma City, Fukushima.

The bringing together of nine panels could not have been done without the energetic and enthusiastic collaboration of a national network of community members. With thanks to Kirsten Leong, Robert Fuchigami, Dana Ogo Shew, Cookie Takeshita and Mas Takano, Clement Hanami, Japanese American National Museum, Irene Kinoshita, Judy Daza, Holly Yasui, Pam Ando, John Hopper, Amache Museum, Jim Nagareda, Japanese American Museum, San Jose, Lynn Fuchigami Longfellow, the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and Karen Yamasaki.

Credits

July 5, 2021

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: David Izu 2016. Ogata Korin – Red and White Plum Blossoms, 18th century. Julie Fukuda, 2014. Tsuchiya Koitsu – Plum Nightingale, 1930. George Ochikubo, Amache, 1942-1945, Woodcarving in center by Yasutaro Takano, 1942-1945.

Panel sections: Fujita carving, David Izu 2018; Ando carving, Tarim Kemp, 2108; Takano carving, David Izu 2018; San Jose carving, Nancy Ukai 2017; Oregon Nikkei carving, Lucy Capehart, 2017; unfinished Morita panel and “no-bird” Morita carving, David Izu 2018; Hanamoto panel, Karen Yamasaki, 2021; Amache panel, family collection.

Special thanks to:

Irene Kinoshita, Judy Daza, Kirsten Leong, Pam Ando, Allison Pace, Holly Yasui, Cookie Takeshita, Mas Takano, Robert Fuchigami, Doug Katagiri, Toshie Morita, Karen Yamasaki, Sandi Morimoto, Clement Hanami, Japanese American National Museum, Ichiro Hanami, Ph.D., John Hopper, Tarin Kemp, Bonnie Clark, Ph.D., Anne Amati, Amache Museum, Junko Kobayashi, Ph.D., Dana Ogo Shew, Sonoma State University, Henry Kaku, Lynn Fuchigami Longfellow, Lucy Capehart, Todd Mayberry, Japanese American Museum of Oregon, Sheri Tharp, Jim Nagareda, Japanese American Museum San Jose, Reiko Homma True, Densho.

Supported in part by The National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program