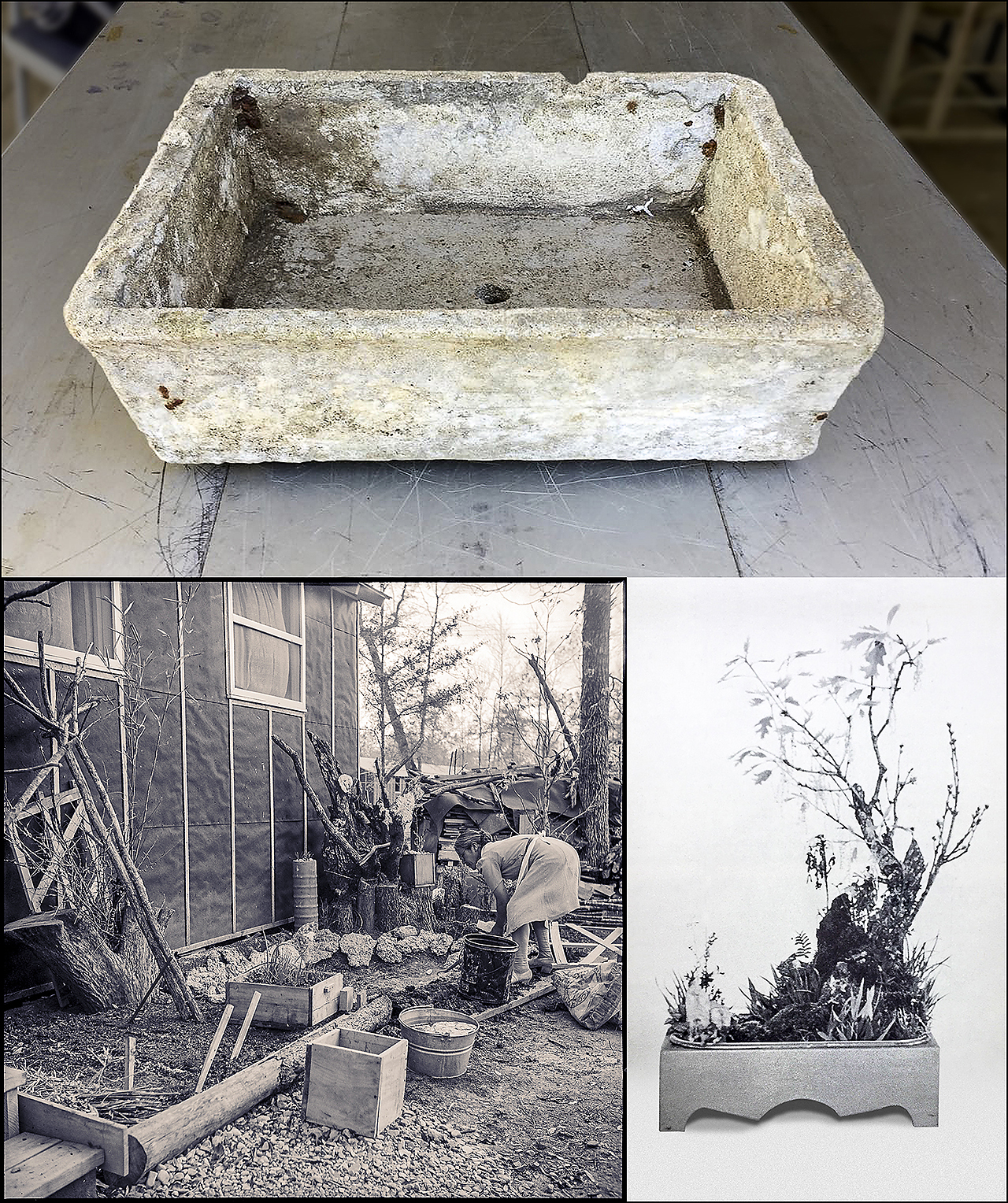

Cement is a porous and homely material for making a bonsai pot but that’s all that was available to Mitsuo George Fujimoto, who was self-taught in the art of training miniature trees. Using cement, chicken wire and a metal pan, the grocery man in his mid-30s made two shallow bonsai containers, one oblong and the other round. He sanded and painted them, creating elegant forms that belied their brutal provenance: a high desert prison in northeastern California.

In September, 1945, three and a half years after they entered the Tule Lake concentration camp, Mitsuo and his wife, Irene, and their two girls, Jean, 11, and Lily, eight, were released. They packed the bonsai pots, two tricycles, a glass washboard and returned to Sacramento, the city they had left under armed guard.

Only 3,500 Japanese Americans returned to Sacramento by the spring of 1946, about half the prewar population. “They have learned that their fears of violence and possible death are unfounded,” according to a Rocky Shimpo news article, “but a majority of them are penniless.”1 The article noted that most returnees had no property, savings or job prospects. “In the haste of evacuation, the Japanese disposed of property at unbelievably low figures. A laundry in Sacramento sold for $1,500 and now can’t be bought for $10,000.”

But the Fujimotos were among the fortunate few who had a small nest egg to return to. An Armenian immigrant couple had leased their mom-and-pop business, the Court Grocery on 7th Street, and deposited the rent payments. Mitsuo and Irene used the money to buy a small house on a block where many other Japanese Americans returning from Tule Lake also eventually moved.

Mitsuo quit the grocery business and became a full time gardener. The house became strewn with magazines about the suiseki art of rock appreciation and bonsai, recalls Dana Kawano, a granddaughter who spent childhood weekends at her grandparents’ home.

The couple transformed the backyard into a tranquil oasis they had longed for in the desert. They built a bridge over a pond that was filled with 24-inch-long koi and constructed tiers for bonsai plants and wisteria. The garden would become a highlight of city garden tours sponsored by the Sacramento Bee.

In the 1950s, several years after his release from Tule Lake, Mitsuo founded a bonsai and rock-viewing club, the Bonsai Sekiyu-kai, which held classes in Japanese for issei and kibei hobbyists who took pleasure in sharing information about the art which, at that time, was not taught outside Japan.

By the time Mitsuo retired from the club, some 20 years later, membership had risen to 100 and had become more diverse, with women and non-Japanese American students, said Yuzo Maruyama, the club president.

It was around that time, in 1972, that a stranger appeared at the Fujimoto doorstep and asked Mitsuo to be his bonsai teacher.

Fred Capellas had tried to shape a lemon tree into a bonsai but when he showed it to his Japanese American friends, they laughed, he said.

“If I’m going to get into this hobby, I need to find a teacher,” he decided.

“Mr. Fujimoto was known as a respected bonsai teacher” and famed for his garden, Fred said in an interview. “I went to his house and knocked on his door. I introduced myself, saying, ‘I would like to learn bonsai. Can you teach me?’”

“Mitsuo asked, ‘how many trees do you have?’

“I said, ‘three to five.’

“Good. Come back next year.”

Fred waited a year.

“One year later, I banged on his door. ‘Do you remember me? Will you still help me?’

“Mitsuo replied, ‘Okay, now I’ll help you.’”

Mitsuo had “a hell of a sense of humor,” Fred said.

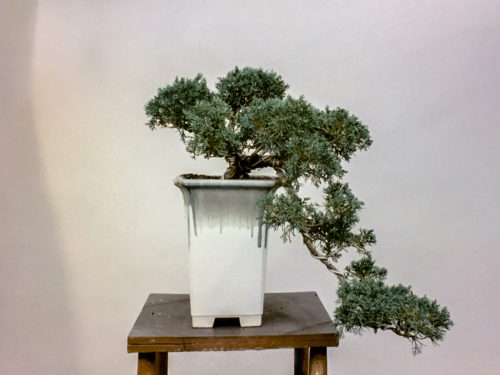

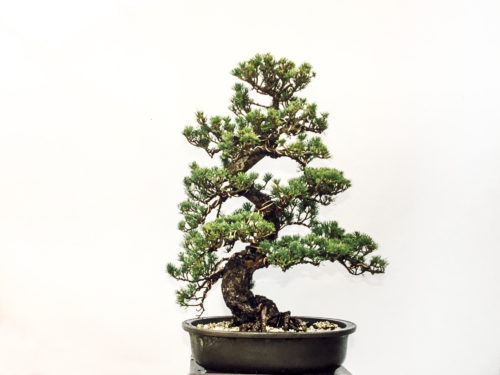

Every Thursday, for the next 11 years, Fred went to Mitsuo’s home and learned how to grow inch-high plants in thimble-sized pots and to prune, wire and repot mature pines, maples and junipers. “It took two years to learn how to water,” Fred said. He learned issei folk methods of guiding growth, such as weighing down branches with lead fishing lures and placing rusty nails into the potting soil to impart iron.

One day, they were talking about containers and Mitsuo said he had something to give Fred. At their next meeting, he came out with the Tule Lake cement pots.

“Mitsuo said, ‘I had to make these in camp,’” but little else and Fred didn’t pry.

Despite harsh conditions in the camps, improvised practices of bonsai took place and cement containers are evidence of such activity. Unfortunately, even if such pots were brought out of the camps, they often weren’t documented as such and may have languished in a garage or remained unidentified after the bonsai practitioner died. Prisoners also made do with what was within reach. For instance, a coffee can was used to start a seed at Topaz, Utah, by immigrant Juzaburo Furuzawa, who lost his Berkeley, California, nursery when he was rounded up in 1942.

Cement was acquired in different ways. It might have been pilfered from a construction site, as was done when issei men who worked on an agricultural crew built an unauthorized monument at Topaz, in 1943, in the memory of James Hatsuaki Wakasa, who was slain by a guard. Cement also was made available by camp authorities for small projects such as making garden ornaments or a koi pond, to keep inmates occupied, lift morale and tamp down incipient unrest.

After the war, rudimentary molds made of fiberglass were used by backyard hobbyists to form cement receptacles, according to bonsai writer and artist Dennis Makishima.

Fred tried to train a tree in the oblong container but it didn’t drain well, so he put both away.

Mitsuo died in 1990 at the age of 83.3 This spurred Fred to give one of the planters to a bonsai friend, Bob Washino, who was interested in containers, was a family friend of the Fujimotos and had been imprisoned at Tule Lake as a child.

In the 1930s, Bob’s father, Shimeta Washino, an immigrant from Aichi Prefecture, used to drive to the Silver Lake area in the Sierra Nevadas with Mitsuo to hunt for wild bonsai stock. On the Fourth of July, friends would gather at Mitsuo’s house, Bob said, and “they would sing, drink and dance. The next morning they would head out for the mountains.”

The friends would return with lodgepole pines and old, wind-sculpted junipers that they pried from cracks between granite boulders. It was tough, physical work but the plants were taken home to be pruned and shaped, and after decades of daily training, a miniature model of nature emerged. The men also collected beautiful stones of unusual shape and coloring that were polished and displayed on stands that they carved by hand.

Bob wanted Mitsuo’s pot to go to a worthy home so he donated it to a respected nonprofit, the Golden State Bonsai Federation.

The organization placed the container in its annual fundraising auction. The high bid was made by The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, which was founded in 1919. Its holdings of 120 acres contain landscaped gardens, an internationally-known European and American art collection and one of the most important bonsai collections in the U.S., displayed in the Japanese Garden.

Fred was pleased to hear of the acquisition and in 2019, when the 50 Objects project interviewed him to learn more about Mitsuo’s pots, Fred decided to donate the second Fujimoto container to The Huntington. “It’s part of history,” he said. “The pots belong together.”

Fred invited Bob and a mutual bonsai friend, Art Sugiyama, to view the container a last time. Art’s family also had been incarcerated at Tule Lake with the Fujimotos and Washinos.

Mitsuo’s pot was placed on a patio table and Fred, Bob and Art sat around it, sharing memories for several hours about Mitsuo.

Art, a retired doctor, said that Mitsuo had given him a five-needle pine in 1985 when he opened a new office but that it did very little for 25 years until he repotted it and “it took off with a burst of new foliage.”

In San Marino, Huntington curator Ted E. Matson was delighted to accept the second receptacle. He is a decades-long practitioner of bonsai and studied under legendary kibei teachers John Naka and Harry Hirao.

He examined the heavy oblong pot, noting that the bottom was lined with corrugated metal from an old-style roasting pan. One side had the rusty imprint of chicken mesh wire, perhaps used for reinforcement.

It’s not known what type of plants Mitsuo might have trained in the vessels. Little plant material was available on the arid terrain of Modoc County and Mitsuo didn’t leave records. The girls, who were young in camp, didn’t think to ask their father about the pots when they grew older. Details have been lost or suppressed, not unlike the stories about what the family endured at Tule Lake, which was the most turbulent of the 10 War Relocation Authority camps, where the government criminalized dissidents they labeled “disloyal.”

Mitsuo never told the girls that in February, 1944, he and Irene signed documents at Tule Lake stating that the family would move permanently to Japan. This must have been a wrenching decision. The document requested “repatriation” to Japan but Irene Sunada was a U.S. citizen, born in 1909 in Folsom, California, and had never been to Japan. Neither had the girls, who were born in Sacramento. Mitsuo was prohibited by racist laws from naturalizing although he had lived and worked in the U.S. for most of his life. Why the Fujimotos didn’t move to Japan isn’t known. Jean, the last living member of the nuclear family, learned of this startling decision when she was shown her father’s government file from the National Archives.

Leaving would have been the end of an immigrant story that had begun 25 years earlier. Mitsuo arrived alone in Seattle at age 12 on Sept. 15, 1919. He had come to join his parents, who were farmers in Placerville, California, and had left him in the care of his grandparents in Yamaguchi Prefecture.

The plucky boy spoke no English but after a week in quarantine, he managed to travel 800 miles south from Seattle on several trains, arriving at the station nearest to where his parents lived. “We don’t know how he knew to do that,” says Jean Kawano, now 88.

That the Fujimoto planters entered The Huntington collection was a surprise to Jean. The vessels are currently on loan from The Huntington for the exhibition, “World War Bonsai: Remembrance & Resilience,” now at the Pacific Bonsai Museum in Federal Way, Washington, along with 70 bonsai, half of which were styled by Japanese American artists. Her father’s pots could easily have been lost or discarded after the war, but now they can be appreciated by others, thanks to a beginner’s failed lemon tree experiment, a kind teacher and a friendship that bloomed.

In memoriam

Fred Capellas died on Nov. 24, 2019, at age 81. He was born in Waimea, Kauai, in 1938, and raised on the Big Island where he was exposed to bonsai as a child when he watched Japanese Hawai’ians tending them. His ashes will be scattered near the beach where he learned to swim, according to his wife, Cindy Capellas, who cared for the bonsai with Fred for 42 years.

Art Sugiyama passed away on Sept. 14, 2019, at age 87. When Art was 12, his mother died of cancer at the family’s third concentration camp at Topaz, Utah, leaving behind nine children. The Sugiyamas had first been removed from Sacramento to Tule Lake, then transferred to the Granada camp (Amache) in Colorado. They were subsequently moved to Topaz. After the meeting at Fred’s house, Art emailed that he had a Topaz artifact: an oil painting that had been in the family since 1945, and was the work of immigrant painter Hisako Hibi, the mother of Ibuki Hibi Lee, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. The painting is a barrack portrait of Ibuki when she was five years old, done as an homage to Mary Cassatt, and a duplicate of an earlier Hibi work. Although Art and Ibuki were children at Topaz at the same time, they didn’t know each other. Art immediately offered the artwork to Ibuki when he learned that her mother had painted it, saying, “I’m happy that it’s going to where it should be.”

The passing of Japanese American community elders and their friends reminds us that we lose not only their warm company but also an irreplaceable source of knowledge and human connection to the WWII artifacts that document the mass incarceration.

| Fujimoto bonsai containers | |

|---|---|

| Oblong pot | |

| Materials | Cement, chicken wire, metal pot |

| Site | Tule Lake, CA |

| Collection | The Huntington, San Marino, CA |

| Round pot B.2016.3.1 | 15 1/4" diameter x 5 5/8" high |

| Materials | Cement |

| Site | Tule Lake, CA |

| Collection | The Huntington, San Marino, CA |

| Photo, right | The Huntington curator Ted E. Matson examines the WWII planter |

Credits

by Nancy Ukai

art direction and banner slideshow: David Izu

Cover Images: landscape by Clem Albers, courtesy National Archives, oblong pot by David Izu, round pot by Andrew Mitchell, Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, other photos courtesy of the Fujimoto family.

Special thanks to:

Jean Fujimoto Kawano, James Kawano, Dana Kawano, Fred Capellas, Cindy Capellas, Robert Washino, Art Sugiyama, Ted E. Matson, Andrew Mitchell, The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, Aaron Packard, Pacific Bonsai Museum, Koji Lau-Ozawa, Yuzo Maruyama, Dennis Makishima, Bob Hilvers, Clark Bonsai Collection at Shinzen Friendship Garden – Golden State Bonsai Federation, Paul Saito, Atsuko Kinoshita, Donna Fujita, Marcia Hashimoto

Supported in part by The National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program