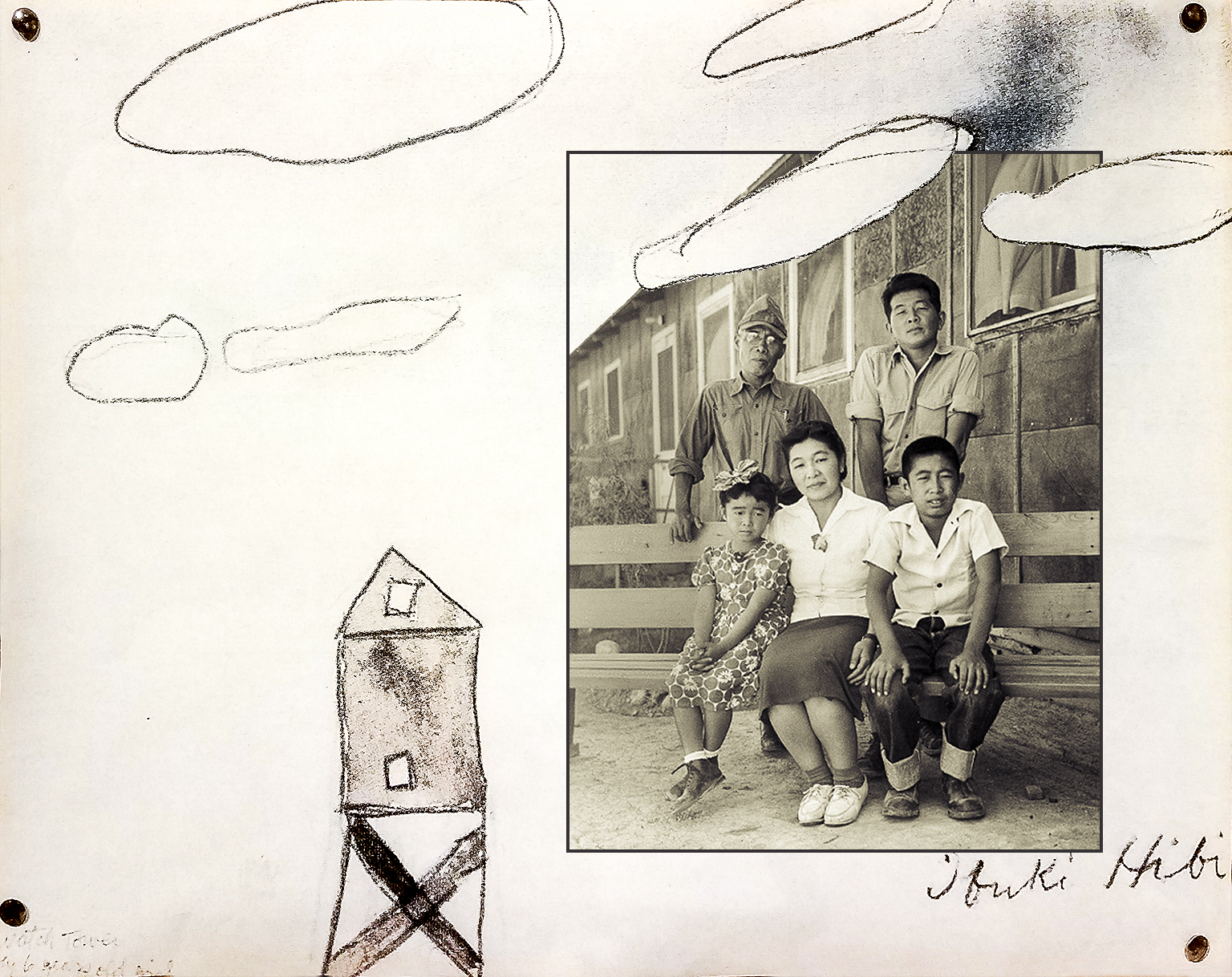

At five years old, Ibuki Hibi was the proud owner of three dolls.

The biggest and most precious of the three, a two-foot-tall German import with a beautiful porcelain face, had been left behind with a family friend.

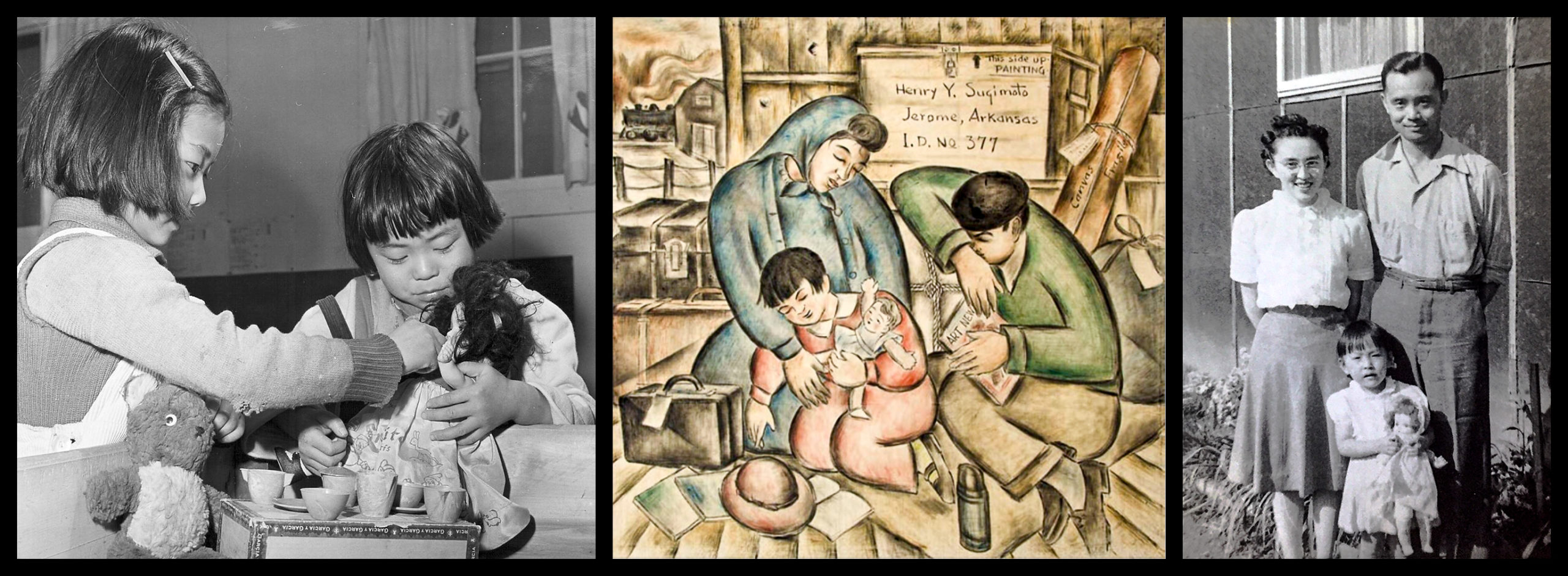

The remaining two were carried into the prison camps, which is what the photographer Dorothea Lange happened to record when she took a photo of Ibuki and her mother, Hisako, each holding a doll, on May 9, 1942, in Hayward, California.

The exclusion notices for “all persons of Japanese ancestry” had gone up just weeks before, forcing the Hibis to quickly reduce their belongings to several suitcases’ worth. Ibuki’s tricycle and her brother Satoshi’s wagon had been thrown onto a peddler’s truck 10 days earlier.1

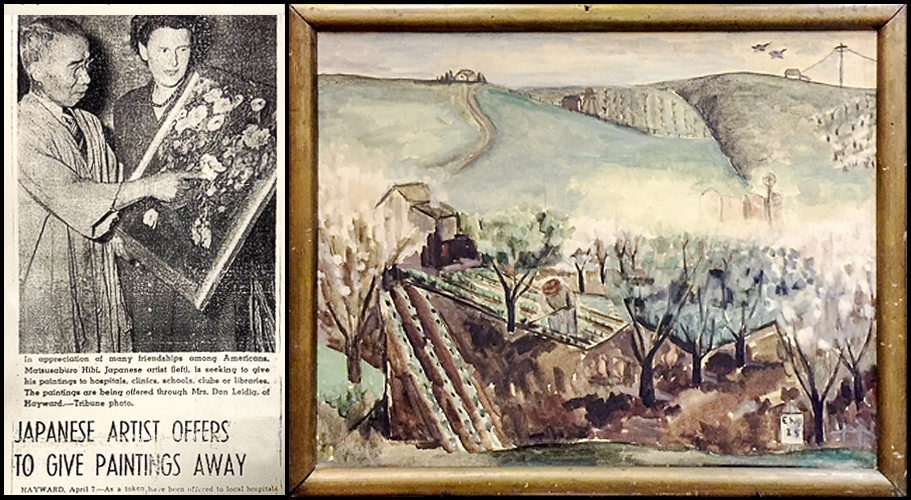

Matsusaburo, her father, a painter, had given away 50 of his paintings and prints to community organizations. Hisako, also a a painter, gave away some of her works, too.

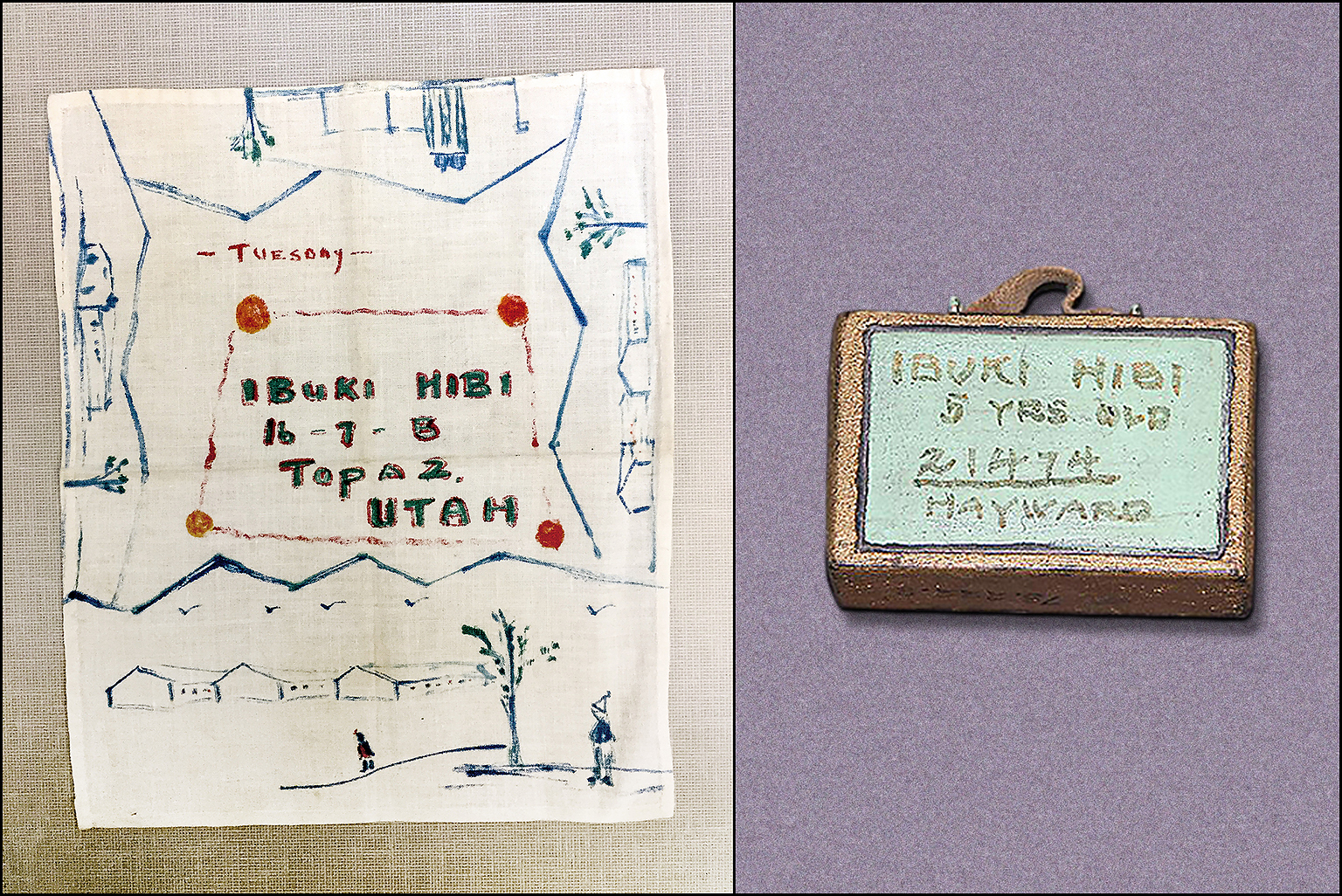

Ibuki, now 83, still has the doll that was photographed on her lap 77 years ago. She said it was carried beneath the guard towers into the Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno and, five months later, into Block 16-7-B of the Topaz concentration camp in the middle of Utah’s Sevier desert.

The war ended and after three years of confinement, the Hibis were released in 1945. The doll was packed again and traveled with the family to New York.

Matsusaburo and Hisako had always wanted to experience the art world in New York City. They found a flat in Hell’s Kitchen on the west side of lower Manhattan. But Matsusaburo was forced to take on small jobs such as painting lamp shades while Hisako became a seamstress. Matsusaburo died of cancer within two years of leaving Topaz but Ibuki says, “my father died of a broken heart.”

Hisako was now a widow supporting two children, Ibuki, 10, and Satoshi, 15. She intermittently found time to care for the doll. Although the timeline has been forgotten, Hisako fashioned a wig of purple yarn to replace the doll’s hair which had fallen off; eventually Ibuki removed it. Hisako stitched a Japanese vest and pink gingham shorts for the unbranded doll. It has its original pink-and-blue cotton dress and its mechanical blue eyes, perhaps made of tin, still blink.

As families were torn from their homes in the spring of 1942, many girls could be seen carrying dolls. The store-bought toys were comfort objects and imaginary playmates that trained the owners to be mothers and to care for something smaller than themselves.

This was before dolls were manufactured in plastic with different skin tones. The dolls that went to the camps had pink skin and often came with blond hair — as “all American” as the girls thought that they were.

Many of the evicted Japanese American families would have had different types of dolls in their households in the early 1940s, including dolls from Japan. Large art dolls with delicate lacquer faces and dressed in silk kimono were not meant to be playthings but were made for display, like the Hina ningyō sets that were brought out once a year to fete Girls Day.

Such “hina” princesses, along with Boys Day warrior figures and ceramic fisherman hoisting a carp, were stored or even destroyed after the bombing of Pearl Harbor because they had the face of the Japanese enemy.

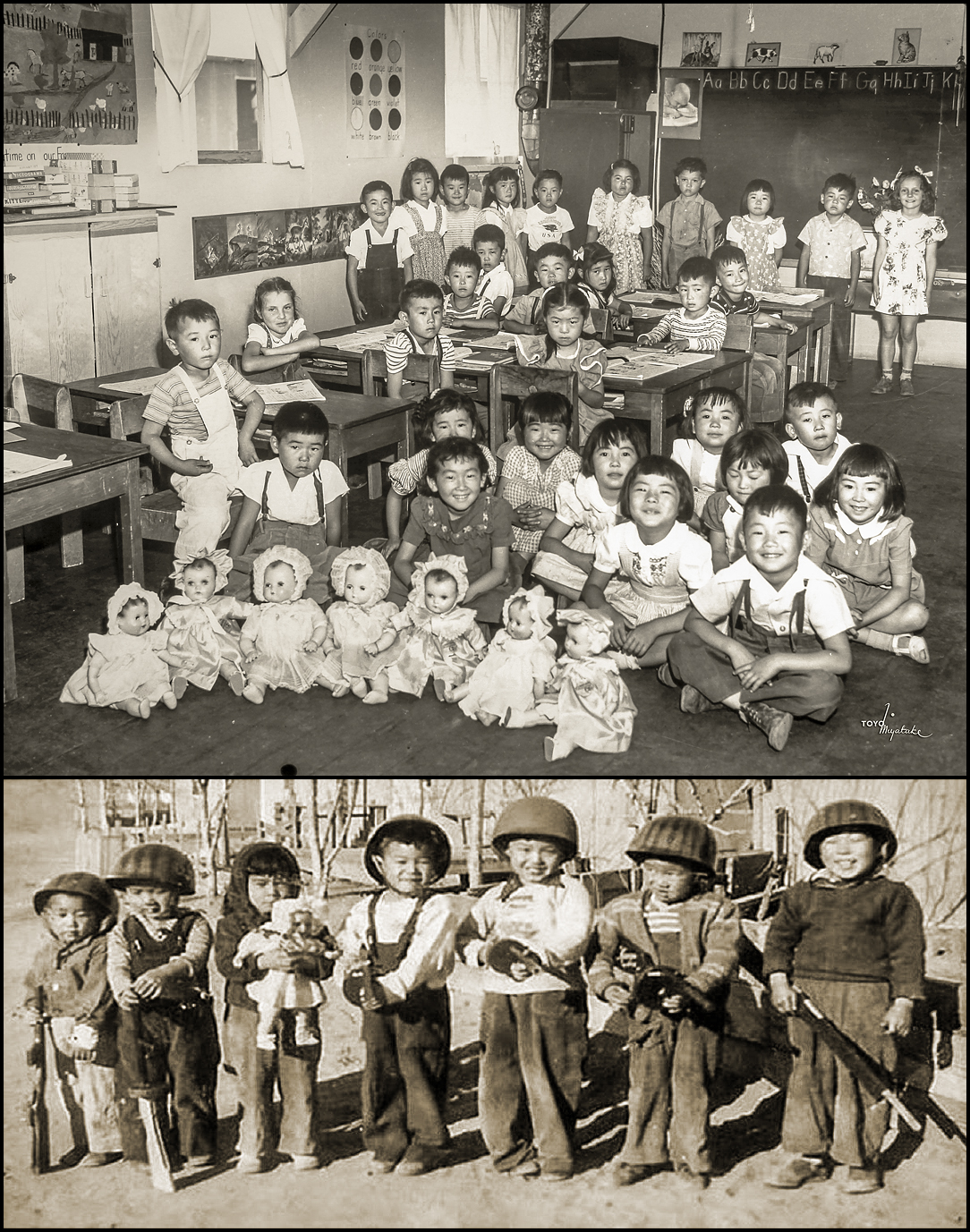

But once the inmates arrived in the camps, a baby boom of dolls erupted.

A donation to Manzanar of baby dolls, perhaps by the Red Cross, was made to brighten the lives of little prisoners. Girls learned to sew rag dolls at Tule Lake. Women crocheted delicate hina sets. Children played with their dolls in the barracks.

Bottom: Amache photograph discovered by Gary Ono, who is in the photo. He titled it “Block 10-E Defense Force.” Gary believes that his aunt, Yuki Okamura, took the photograph of seven children, aged three to six, to send to her sister, Kimiye Ono, who was convalescing in Boulder, CO, from tuberculosis, separated from her four children. “These little GIs, well-armed, look ready to defend their own Block 10-E, with a nurse ready, just in case,” he wrote in a 2019 Amache newsletter. From left: Haruo Roy Otsuji, unidentified, Yae Phyllis Okamura, Hiroichi Kenneth Okamura, unidentified, Tsutomu Gary Ono, Kazumi Stanley Ono (1939-2018). Courtesy Gary Ono.

Kimi Saito, a nisei mother pregnant with her second child, made an amusement for the unborn baby. She strung pink and blue wooden beads on elastic, used bells for hands and handpainted facial features on a head made of fabric. A leather Japanese thimble was attached to the top so that when the toy was held for the baby to pull, the doll jumped and jingled. It was made sometime around the time that her daughter, Teiko, was born in Minidoka, Idaho, on April 23, 1943.

“It shows its use,” says Teiko. “I must have enjoyed it a lot since it had bells that caught my attention as a child when I shook the elastic that held it together. It’s too bad the face is so dark since it hides the eyes, nose and mouth she put on the doll with ink.”

When Teiko was 14 months, her mother died at the Minidoka hospital of sepsis from the rupture of an internal organ. She was 35. The large blue button she placed below the doll’s torso fastens her love to Teiko.

Hisako and Ibuki returned to California in 1954. Satoshi had gone to Utah to attend college. The doll was put away and years after her mother died in 1991, Ibuki found it in a closet. She doesn’t feel a strong emotional attachment to it.

The photograph of the two holding Ibuki’s dolls evokes a strong reaction in viewers, however. The image of the stoic mother and innocent child being cast out by racial hatred and economic greed has been reproduced for exhibitions, books and films and was included in a 100-foot-long mural in south Berkeley by the artist Edythe Boone, who lost a nephew, Eric Garner, to police violence in 2014.

Ibuki says about the photograph and the doll, “it was a moment in time. I don’t remember much about it. ” Perhaps the doll belongs more to the public memory than to Ibuki.

She feels closer to the things that her parents made for her while the family was incarcerated: cotton handkerchiefs; a small nametag in the shape of a suitcase; a wooden swing that exists now only in Ibuki’s memory.

Her father had made her a small wooden swing outside the barrack. “There was a little boy who wanted to use the swing and he liked it so much that I complained to my father,” Ibuki said. “And my father just told me, ‘In this kind of environment we’re living in … you have to share with other children who don’t have a swing.’ I still remember him saying that I have to share what I have with others.”

His words never left her and Ibuki now imparts his kindness and spirit of generosity to her nine grandchildren, aged eight months to 18 years.

Meet Ibuki and Satoshi. This Saturday, Dec. 5, they will discuss the doll, childhood at Topaz and the effect that the war had on their family in an online program sponsored by the National Japanese American Historical Society and 50 Objects, from 11 a.m. to noon PST. Register for the free program here.

| Ibuki's Doll | |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 12 1/2" x 5 1/2" x 3 1/4" |

| Material | composition, metal |

| Date | ca early 1940s |

| Creator | no company marking |

| Sites | Tanforan, CA, Topaz, UT |

| Other | 12 bandaids placed on different parts of doll's body |

| Photo caption | Ibuki with doll at the memorial reunion of Hayward residents removed in 1942. Hayward Public Library, Nov. 8, 2019. |

Ibuki's memories

Issei painters

Hisako Shimizu Hibi (1907-1991) was born in Fukui Prefecture and came to the United States in 1920, graduating from Lowell High School in San Francisco. “My mother, who was more than 20 years younger than my father, took an interest in art when she was in high school because she wasn’t able to write well, she said, but she was able to express herself through art. So she went to the same art school in San Francisco, the California School of Fine Arts, and met my father there, who was at the right age to settle down,” Ibuki said.

Matsusaburo Hibi (1886-1947) was born in Shiga Prefecture and immigrated to the U.S. in 1906. “He had come to this country with such high hopes.” Before he married Hisako, “he was very busy in the community trying to help other Japanese families and other Japanese who were coming to this country.” They were married in 1930.

At Topaz with father

After the departure of artist Chiura Obata, Matsusaburo became director of the Topaz Art School.

“I was my father’s sidekick. I walked across the desert sand almost everyday with my father to the art school and coming back. I remember him instructing others in painting, drawing, sketching. And also carving linoleum blocks and wood blocks. He loved doing art.

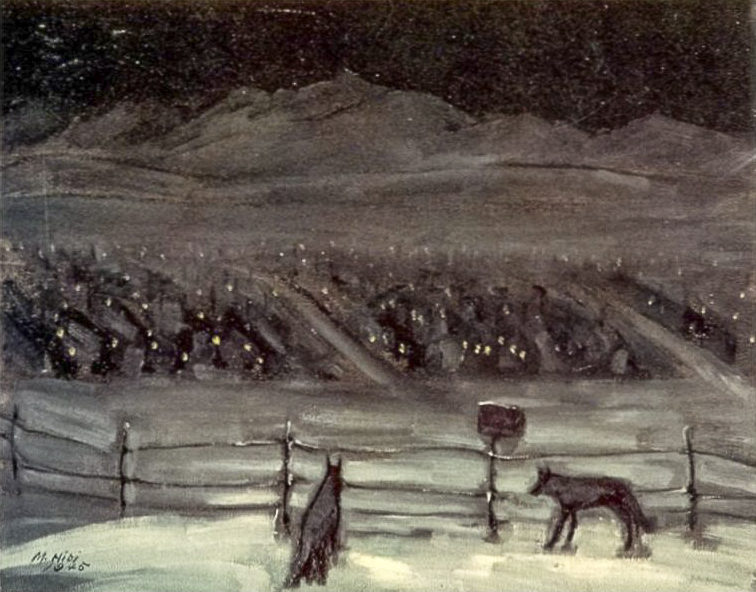

“My father would hear the coyotes howling at night and he imagined them around the mountains of Topaz so he did many paintings and wood block prints with wild animals but especially coyotes.” Photo: Hibi’s Topaz WRA Camp at Night, 1945. It graced the cover of the 1992 catalog, The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942-1945. A New York Times art reviewer wrote: “Hibi used the image of coyotes in the camps to evoke a sense of danger, but who is threatening whom? Do the coyotes represent the internees, their jailers or simply themselves? Hibi’s paintings, luminous and eerie, leave the question open.”

Hisako's homage to Mary Cassatt

Hisako painted herself washing Ibuki’s feet in their Topaz barrack in an homage to Mary Cassatt. She wrote on the back of the canvas, “My daughter.” Ibuki edited her mother’s memoirs which were published in 2004 by Heyday Books and the painting was used for the cover.

“My mother had been working on a manuscript since the 1950s. It took a decade. When I came across it after she passed away … I didn’t change any stories and didn’t change her format but I edited the mix a little for publication.”

The painting was featured in the exhibition The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942-1945, and traveled across the U.S. and to Japan in the 1990s with Matsusaburo’s painting of coyotes at Topaz.

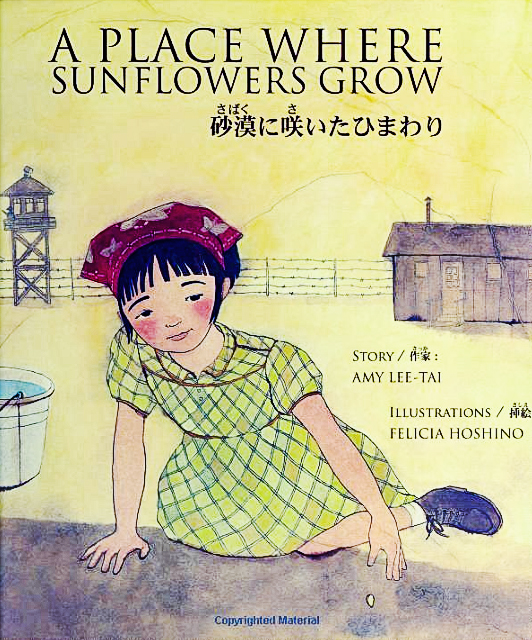

Planting seeds

Amy Lee-Tai, Ibuki’s daughter, wrote and published a picture book, A Place Where Sunflowers Grow, about a small girl at Topaz who plants sunflower seeds in the barren desert. Although the main character is fictional, the author said in an interview, “Sunflowers really did bloom at Topaz. My mother and grandmother planted sunflower seeds, and they grew to the top of the barrack wall. To me there is something so lovely in that act of planting seeds in the barren desert behind barbed wire. It was such an act of hope.”

The book is bilingual in English and Japanese. The illustrator, Felicia Hoshino, is a descendant of incarcerees at Poston, AZ and Minidoka, ID.

Twelve yellow band aids

crackle spread like a spiderweb laid

over the remade cracked plate face

of a doll of 77 years

a concentration camp survivor

along with its owner then a girl of 5 her name Ibuki

now 82 she too keeps alive

an embodied memory

This could be a pretext

for cross cultural aesthetics

the nobility of endurance

wabi and sabi embedded

in a passage of plastic

threaded through time

a model of a minority sublimely triumphant

or not

The doll’s eyes wide

her mouth shut small

she’s seen so much

said nothing at all

David Izu 6/2019 – 6/2020

Credits

by: Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

banner cover images: doll photos by David Izu, historical photos of Hayward, CA and the Topaz concentration camp by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives. Photo illustrations by David Izu

Special thanks to:

Ibuki Hibi Lee, Satoshi Hibi, Teiko Saito, Kimiko Marr, Frances Kitamoto Ikegami, Dan Barry, Bainbridge Island Historical Society, Katy Curtis, Windgate Museum of Art, Hendrix College, Alan Miyatake, Toyo Miyatake Studios, Alisa Lynch, Manzanar National Historic Site, Gary Ono, Amache Historical Society II, Kerry Yo Nakagawa, Erica Harth, Heyday Books, Amy Iwasaki Mass

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service Japanese American Confinement Sites program