When Tokinobu Mihara had an idea, he usually found a way to make it happen. What he envisioned, even as he was losing his eyesight, was a new system of Japanese braille that could be laid out on a wooden board so that others who were blind could learn to read using their fingertips and connect to the world.

Completing such a board became his goal. “My arms and legs were robbed of their freedom,” he wrote, “but the government could not restrict my thoughts and my time.”1

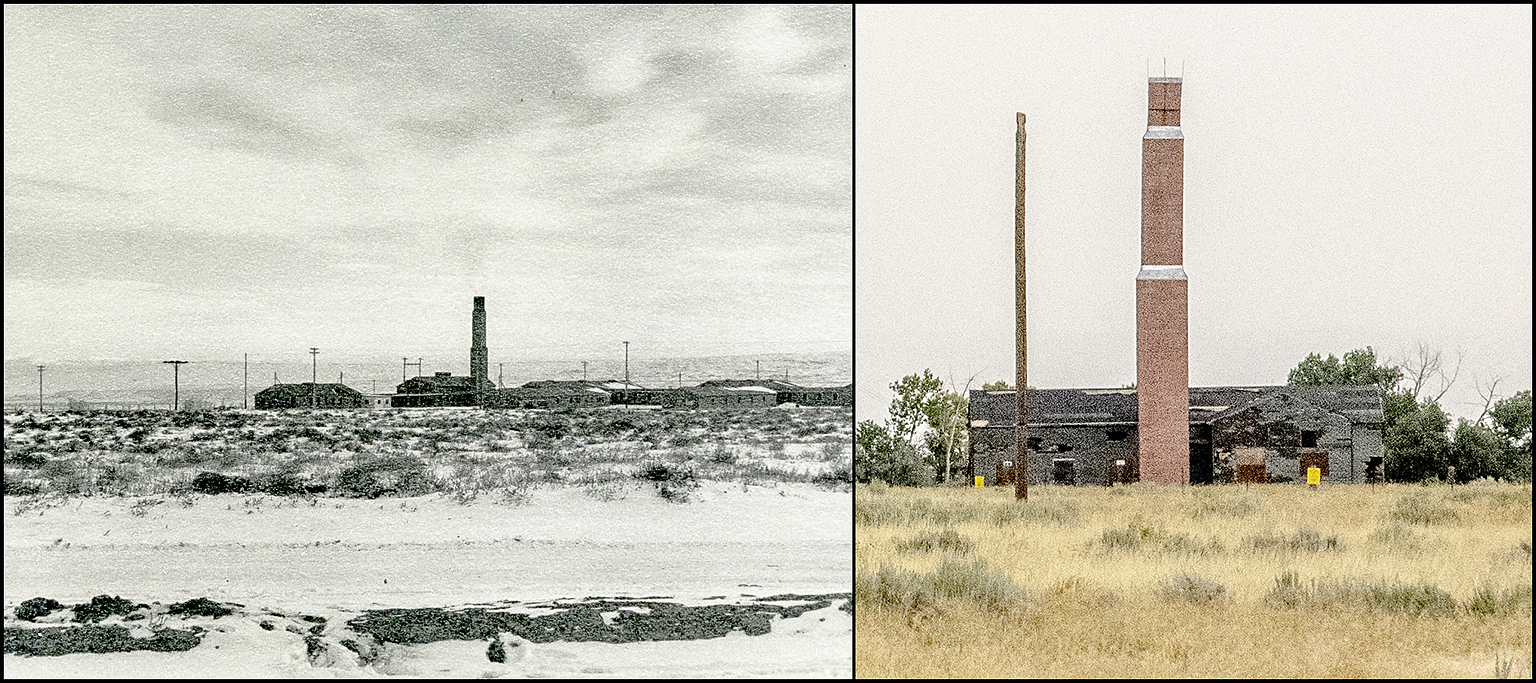

Tokinobu’s braille board, unique in the material history of the Japanese American incarceration, was made during an especially traumatic year. Tokinobu was a writer and editor whose wife, two sons and parents were incarcerated at the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming, more than 1,000 miles from San Francisco, their home.

On August 6, 1944, Tokinobu’s father died of cancer at the camp hospital. He had been the first of the Miharas to emigrate to the U.S.

In 1902, when Tokinobu was only five, his father, Tsunegoro, left Matsuyama on Shikoku island for San Francisco, to lift the family’s fortunes.

For the next 18 years, Tsunegoro made a living as a producer of miso soy paste and sent his earnings back to Japan.

The rest of the family joined him in 1920, never dreaming that his final days would be spent in a barren camp hospital with colon cancer. When Tsunegoro said goodbye to his American-born grandson, Sam, he placed a quarter in the child’s hand.

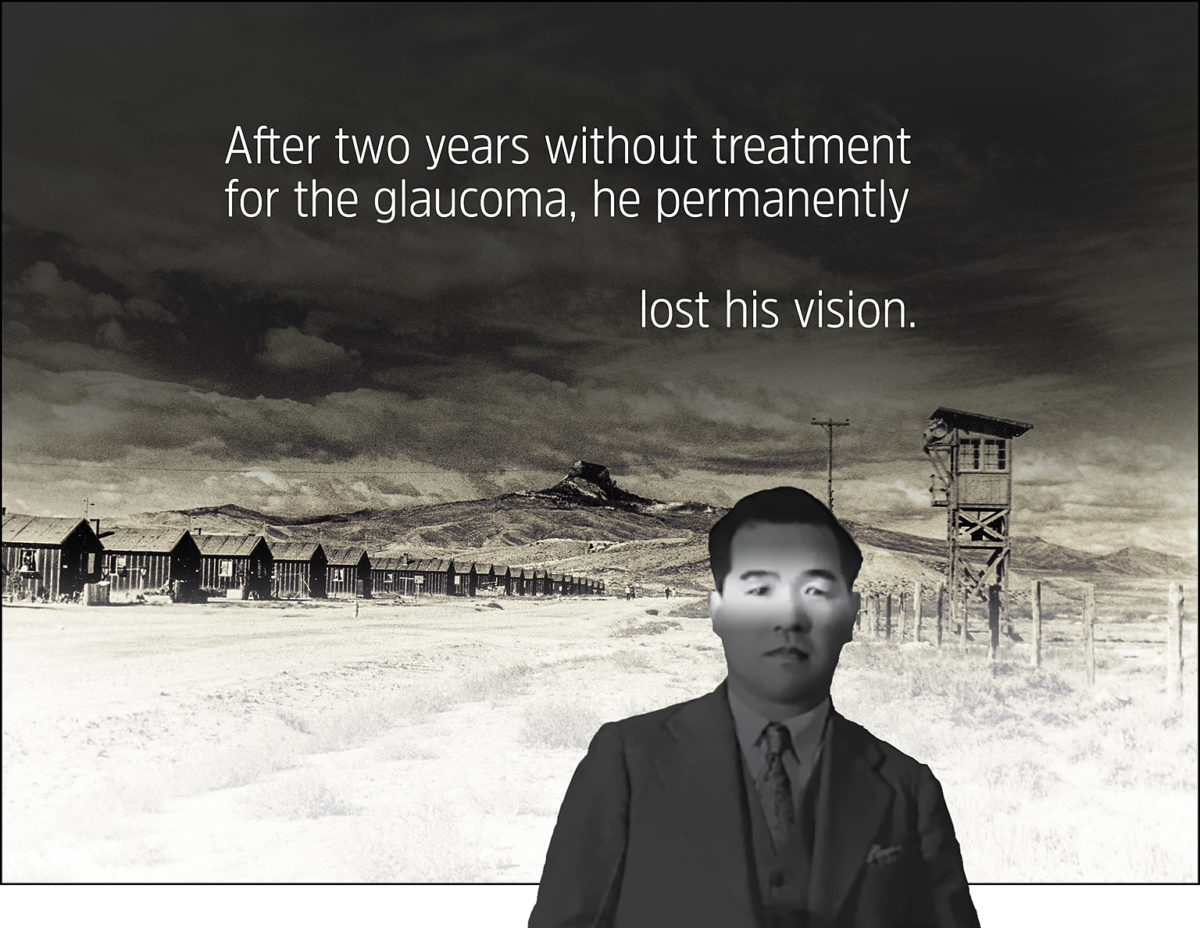

Even as Tokinobu was grieving the death of his father, he was losing his eyesight. He suffered from glaucoma in both eyes. Without the care of his San Francisco ophthalmologist who had managed his case for 17 years, his condition rapidly worsened.

Sam, the younger son, was 11 at the time. “General DeWitt would not allow my father to visit his specialist,” Sam said, referring to the head of the Western Defense Command, “so I watched my father become blind.”

In early November, Tokinobu was issued a day pass to visit a hospital in Billings, Montana. The visit confirmed that Tokinobu had permanently lost his vision.

Losing his vision sharply curtailed his ability to earn income and get around Block 14. Eating at the mess hall was difficult and required Sam and Nobuo, his older son, to guide him there, so he ate in the barrack more often than not. For the first 18 months, Tokinobu had worked as a translator at the camp newspaper, the Heart Mountain Sentinel, but he was forced to quit when he could no longer read the print.

His monthly pay in San Francisco had been $120 at the New World (Shin Sekai) newspaper, compared to $19 a month at the Sentinel. But even this meager income was now gone. Suyeko, his wife, had quit her mess hall job due to neuritis.

Daily life required money for odds and ends. “They have to buy food because he feels dizzy in the mess hall. Have to buy shoes for the boys,” wrote a camp social worker during a September meeting.3

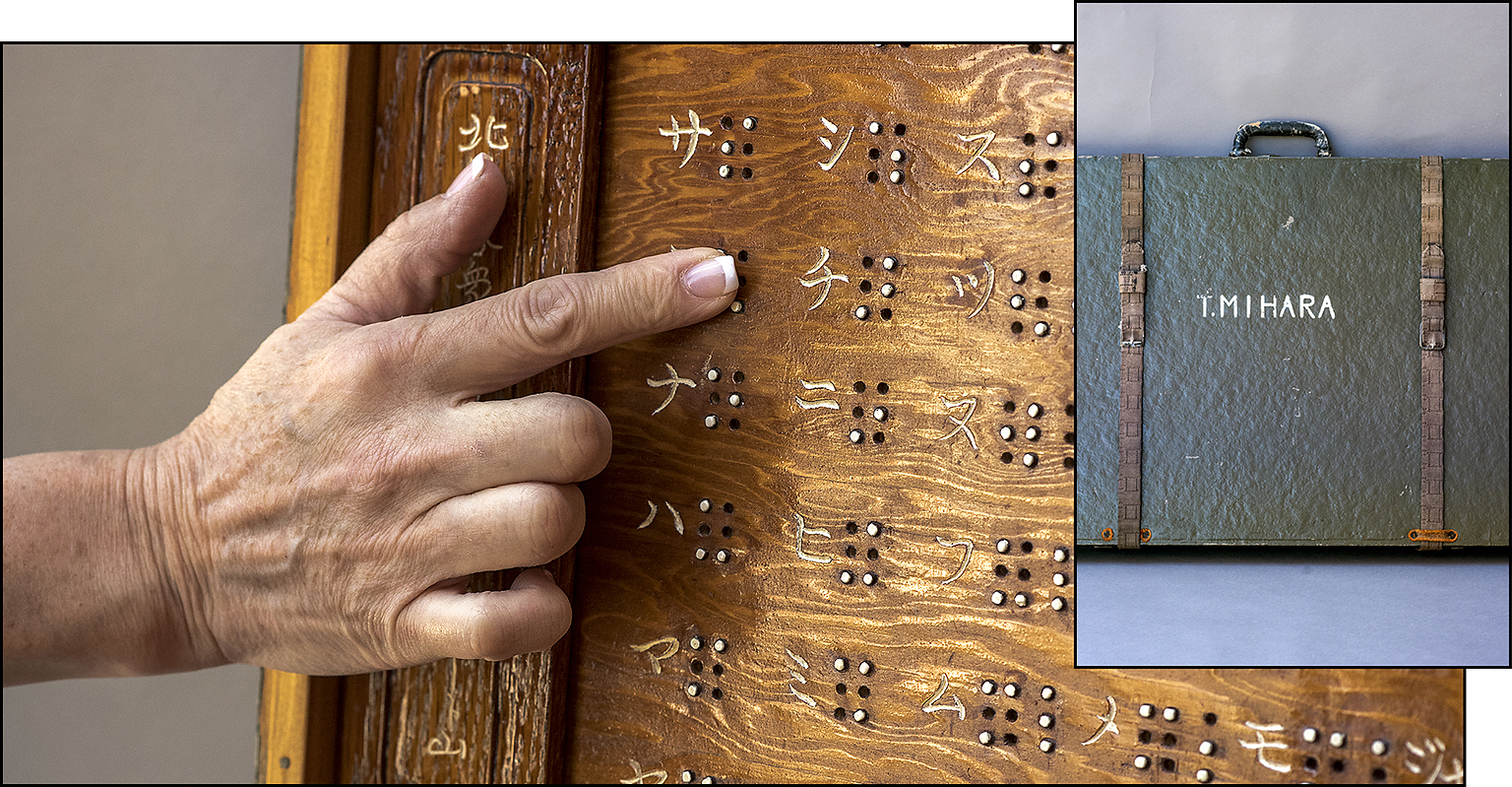

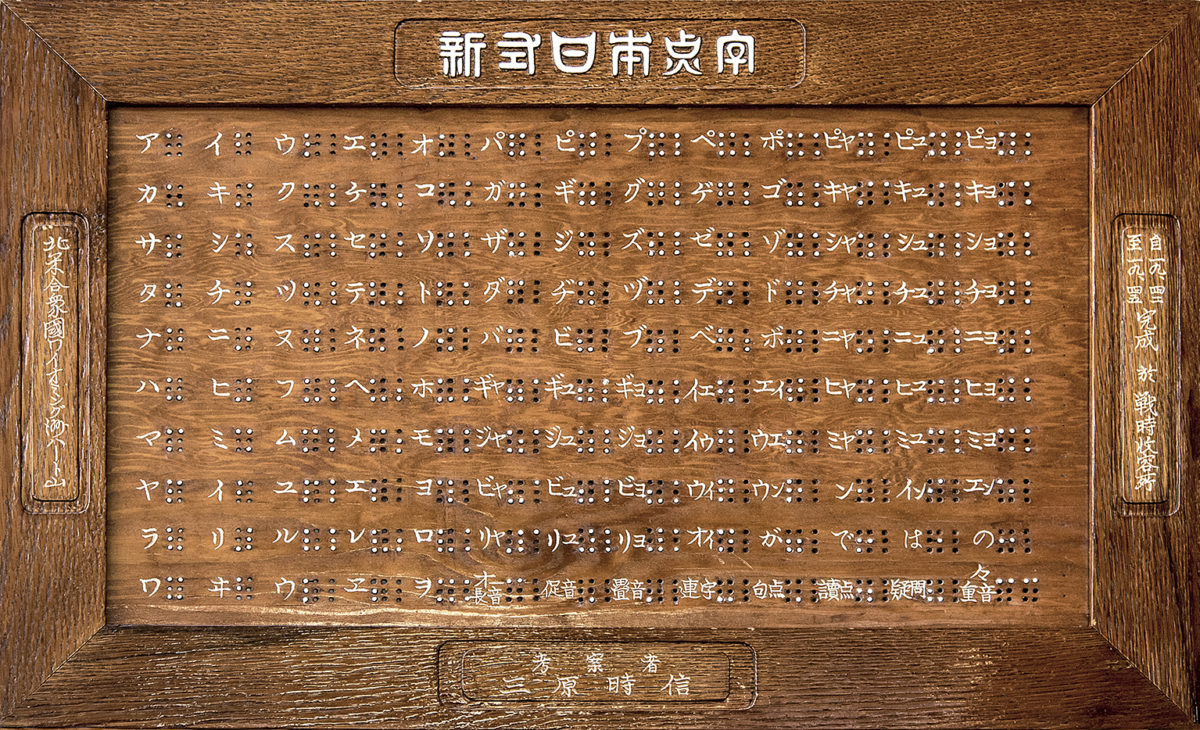

But in the same interview, Tokinobu revealed that he would like to teach Japanese braille using a system that he had invented. It was thoughtfully laid out on a large instructional board that he had commissioned an elderly prisoner in Block 23 to make.

Tokinobu explained that there were four or five blind people at Heart Mountain and that he was already teaching braille reading to a young woman from Washington, 19-year-old Mae Kumashiro. The camp put Tokinobu on the payroll as a teacher of the blind from Dec. 1, 1944.

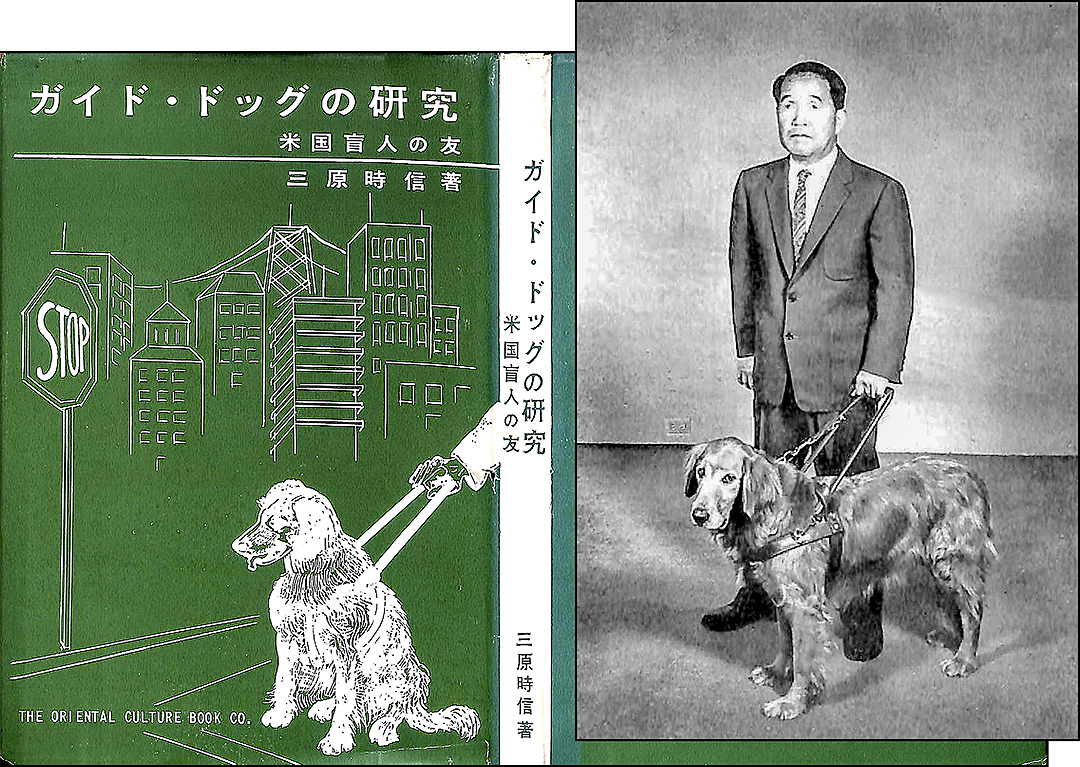

In the 1940s, visually impaired people were not considered to be useful members of society. Tokinobu defied this characterization. When he learned that he had glaucoma, he went through periods of severe depression, Sam says, but his father’s Christian faith and a strong drive to be productive led him to continue to write, publish and educate.

The Japanese braille code Tokinobu created at Heart Mountain used a system of raised dots for written characters, sound combinations and punctuation based on the convention of using two columns of three cells each, with variations, including an additional row.

Inside the camp, Tokinobu had learned English braille by studying materials sent to him by friends from the Crafthouse for the Blind in San Francisco.5 He then decided to create his own Japanese braille code even though Japan had adopted the Ishikawa system in 1890. It presented an intellectual challenge for him during incarceration and also was rooted in his conviction that improvements could be devised.

The Mihara system was informed by Tokinobu’s life-long passion for language and communications. At Waseda University in Tokyo, he majored in English and minored in Hebrew.

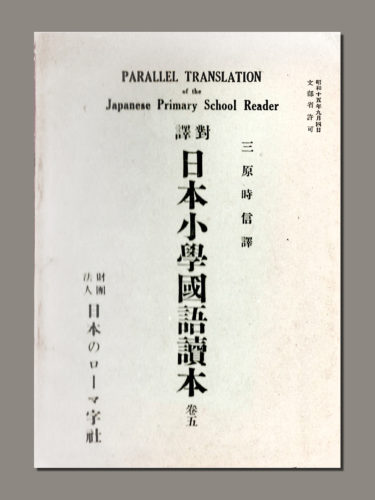

The system also incorporated his interest in romaji, the use of Roman letters to write and read Japanese. After living in the U.S. for many years, he determined that the next generation of Japanese American children would never learn Japanese if they had to memorize some 100 kana in two syllabaries and 1,952 Chinese characters — just to read a newspaper.

He became an ardent proponent of teaching Japanese without using kana or kanji and even converted a series of Japanese elementary school readers into romaji, which drew suspicion from the FBI.

Tokinobu enlisted the help of a 72-year-old issei, Shigeichi Usami, to create the braille board. Usami was a single man from Shimane Prefecture. His refined script and meticulous woodworking skills suggest a life beyond his occupational record, which included years as a laborer for the Southern Pacific railroad.6

Experts in educational materials for the blind say that paper was used in the 1940s and that an instructional board made of wood would be unusual. “Unlike braille paper, such a board would be durable, and easy to clean. Heart Mountain was probably a dusty, windy place and for instructional materials that were to be passed around and used by several students, the more durable the better,” surmised Greg Kehret of the San Francisco Lighthouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired.

Wood, which was available to inmates, is also “warm to the touch and familiar to Japanese people,” adds Hiromi Kishi of the Japan Society for Blind Education in Kyoto.9

Only six months after Tokinobu began teaching, the family was approved for release.

Tokinobu and Suyeko had wanted to return to San Francisco but they feared the racism that might greet them. Their house on Sutter Street had been broken into and everything stolen. Then Tokinobu was informed by the Army that he was prohibited from returning anyway.

The family packed up the board with their barrack belongings and moved to Salt Lake City on June 28, 1945, with Tsune, the boys’ widowed grandmother. The Miharas opened a book shop on South West Temple Street, in the small Japantown two blocks from Temple Square and the headquarters of the Church of the Latter Day Saints.

The shop struggled. In three years, perhaps in the summer of 1948, the family finally returned to San Francisco.

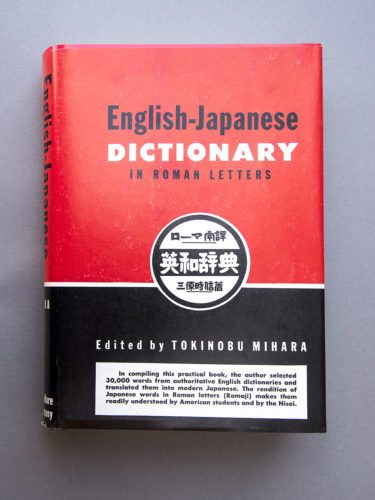

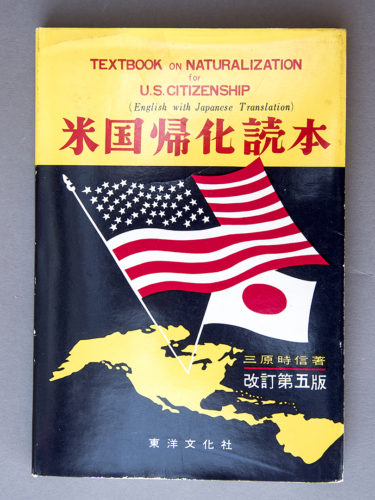

While incarcerated, Tokinobu had also compiled an English-Japanese romaji dictionary with 30,000 entries. He and Suyeko decided to start a small publishing firm in the basement of their Victorian home and rented out the other rooms. Tokinobu taught English to Japanese war brides and wrote a book about U.S. citizenship regulations.

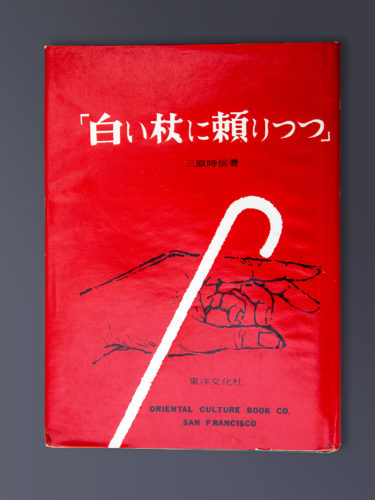

Research by Hiromi Kishi so far reveals that Mihara wrote 17 books, all but two in Japanese and most after he lost his vision. Tokinobu’s autobiography, Guided By My White Cane (白い杖に頼りつつ, 1962), describes his religious devotion and how it inspired his appreciation for life’s gifts. Tokinobu continued to think about his braille system, even considering how abbreviation styles used in Morse code and Gregg shorthand could be applied to braille.

The only books Tokinobu wrote in English were two slender volumes which he co-authored with Suyeko about the art of origami folding. They were among the earliest instructional materials in English.11

The couple’s five-year-old granddaughter, Linda, learned to fold by following the illustrations. She and her sister, Vicky, became origami artists, teachers and authors. Linda is co-owner of the Paper Tree gift shop in San Francisco’s Japantown.

The shop is located one block from the former Mihara family home which was sold to the Japanese American Citizens League. Its national headquarters was built on the site.

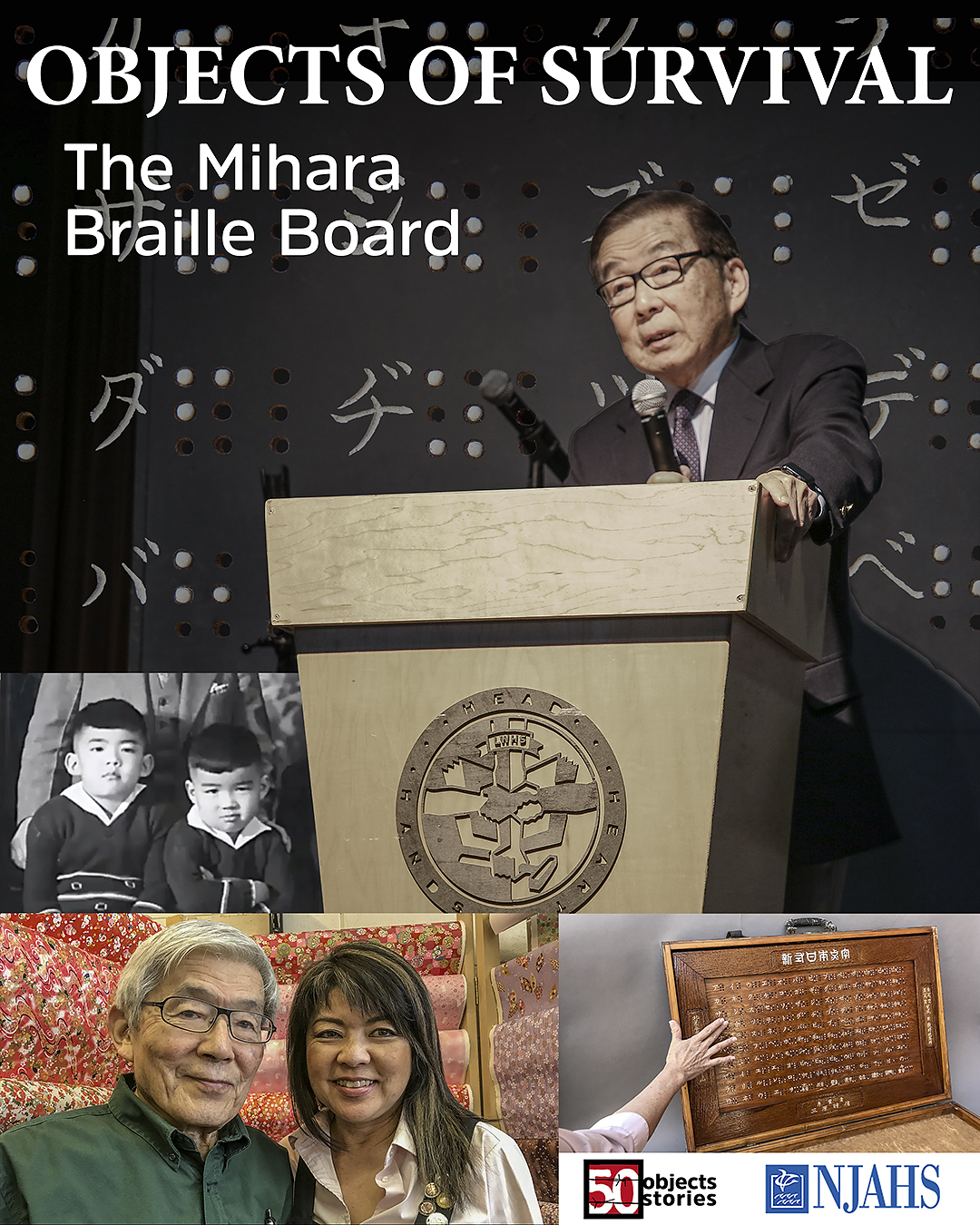

After 41 years as a rocket engineer, Sam started a second career as a national speaker on Japanese American incarceration. He has delivered his powerful slide lecture to close to 60,000, before high schools, civic groups, the law schools at Harvard and Yale and at his alma mater, U.C. Berkeley. He was awarded the Paul A. Gagnon Prize in 2018 by the National Council for History Education.

Displaying the same individualism and productivity as his father, Sam also has visited immigrant detention centers and federal prisons to investigate carceral conditions and report his findings. This has led him to protest family separations and to support Black reparations and the Congressional HR40 bill.

Sam learned that his father had visited San Quentin to speak about his religious faith, a fact that surfaced when an unpublished English translation of Tokinobu’s autobiography recently surfaced. Suyeko was distributing copies in 1978, a year after Tokinobu died at age 79.

In 2019, before the pandemic shut down national travel, Nobuo and Sam donated their father’s braille board to the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. A unique object of war, born of faith, determination and injustice, returned to the place of its birth.

In his memoirs, Tokinobu imagined a day when “a certain machine can be pressed against a book written in English or romanized Japanese and the printing is changed to sound.” With the advent of smart phones and apps, that day is arriving. Tokinobu’s board will continue its work in analog and digital forms, educating about racial injustice and illuminating the life of its inspired creator.13

| Mihara Braille Board | |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 28 3/16 in. high x 18 in. wide x 3/4 in. deep |

| Material | Hardwood, paint. The case may have been made after the war. |

| Date | Board ca. 1944. The braille system developed from 1942 and continued to be refined for years after. |

| Creator | System and project by Tokinobu Mihara. Board lettering and woodworking by Shigeichi Usami. |

| Site | Heart Mountain, Wyoming |

| Collection | Heart Mountain Learning Center, Wyoming |

| Photo caption right | Board with map showing Heart Mountain |

Saved from the Fireplace

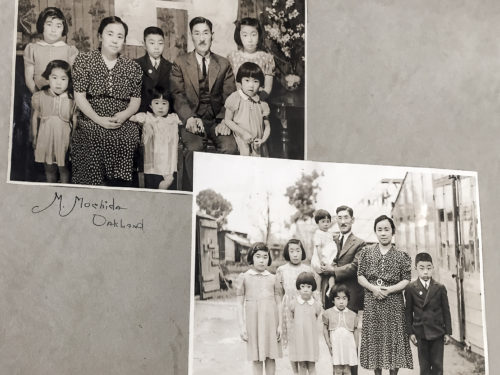

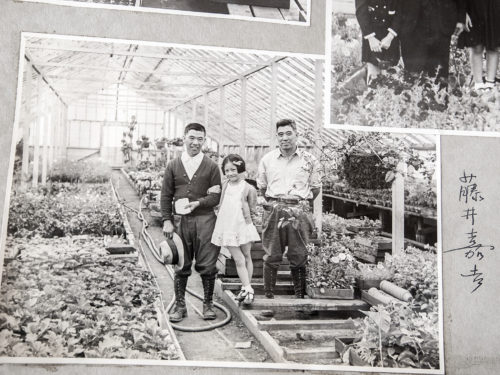

The “fireplace was going night and day,” Sam recalls. “Right after Pearl Harbor, my father was burning photographs and film. He was trying to destroy evidence that the government might tie to espionage activities. In that process, he destroyed a lot of family photos.” Only a handful of family photos and an album of Tokinobu’s photos of area flower growers survived. Tokinobu was an avid photographer with a home darkroom. In the album is a prewar photograph of the Mochidas of Oakland, who operated a nursery in Eden Township. It shows the family years before an iconic image was made of them by Dorothea Lange as they awaited removal in April, 1942, in Hayward, California. Courtesy Mihara Family Collection and National Archives.

Join us for a digital event and meet Sam, Nobuo, and Linda, the sons and granddaughter of Tokinobu and Suyeko Mihara. Sponsored by National Japanese American Historical Society and 50 Objects.

Date: Saturday, Jan. 23, 2021

Time: 11am – noon PST

Register here

Credits

by: Nancy Ukai

art direction and banner cover design: David Izu

banner cover images: Mihara family images courtesy of the Mihara Family Collection. Heart Mountain drawing by Estelle Ishigo. Other photos by David Izu and Evelyn Lee.

Special thanks to: Sam Mihara, Nobuo Mihara, Linda Mihara, Hiromi Kishi (Japan Society for Blind Education), Chiaki Shiba, Stacey Camp, Dakota Russell, Brendan Daake, Heart Mountain Interpretive Center, Reiko True, Greg Kehret, Esmerelda Soto, San Francisco Lighthouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service Japanese American Confinement Sites program

This object/story presented in collaboration with the National Japanese American Historical Society