The Paintings

In 1941, Gene Sogioka was a 26-year-old background artist at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. He had worked on Fantasia, Dumbo and Bambi and was getting ready to hold his first solo show.

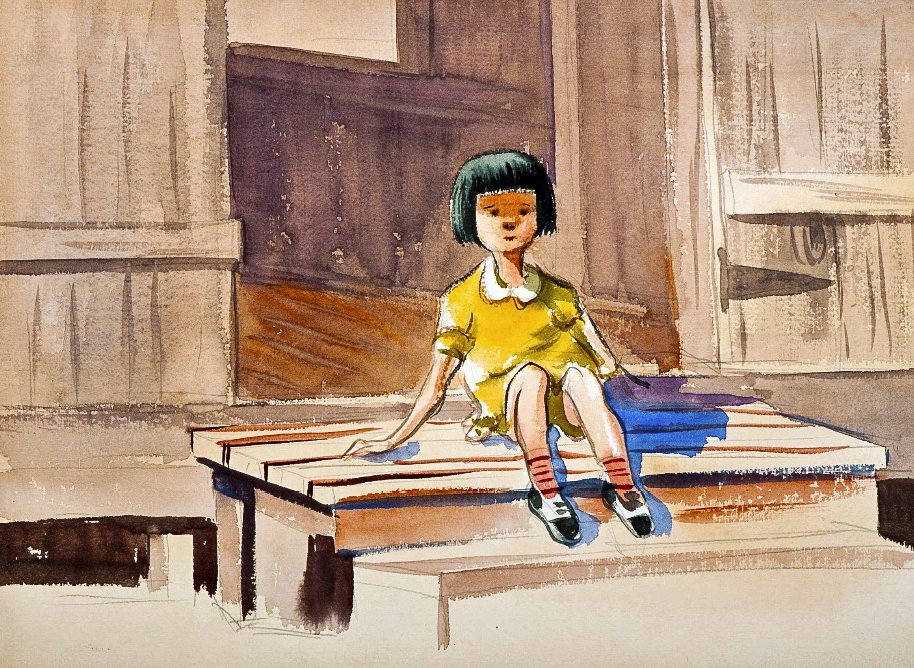

“Little Girl in Yellow”

Two years later, from a cramped barrack in the Arizona desert, where the rattlesnakes were as big as his arm, Gene put the finishing touches on what was to become his artistic legacy: a unique record of the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

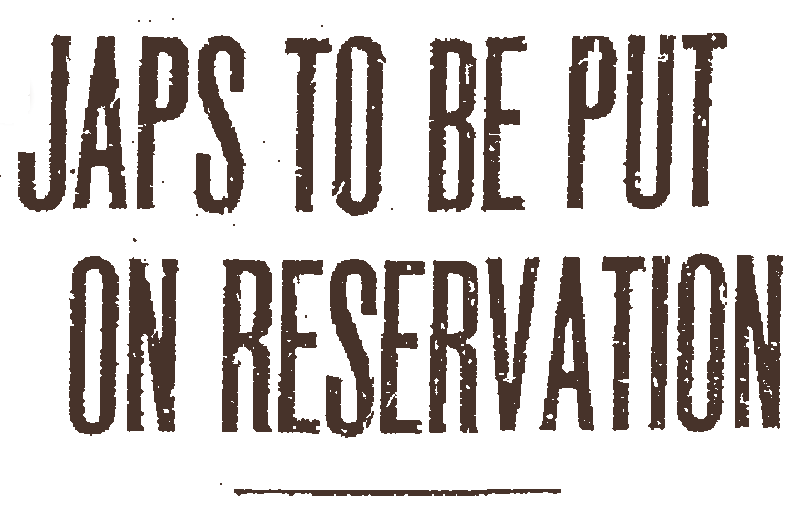

After Roosevelt’s presidential order banned people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast, Sogioka was sent with his extended family to the Poston camp on the Colorado River Indian Reservation.1 It was the second largest of the U.S. concentration camps, holding 18,000 civilians, mostly U.S. citizens.

He had taken some of his artwork with him and was subsequently hired by a government project to document what he saw. Free to paint without constraints, Sogioka created 134 watercolors between 1942-1943.

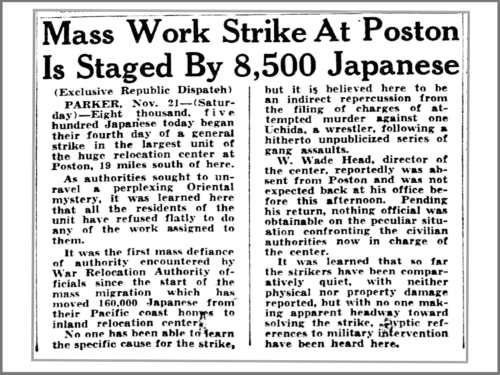

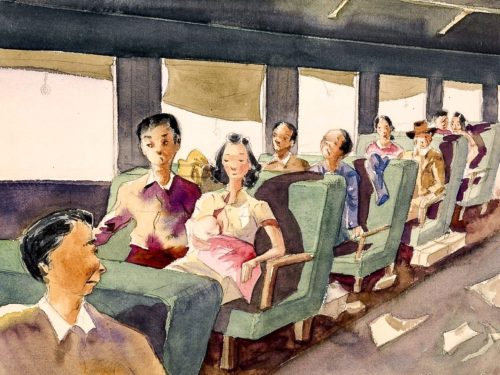

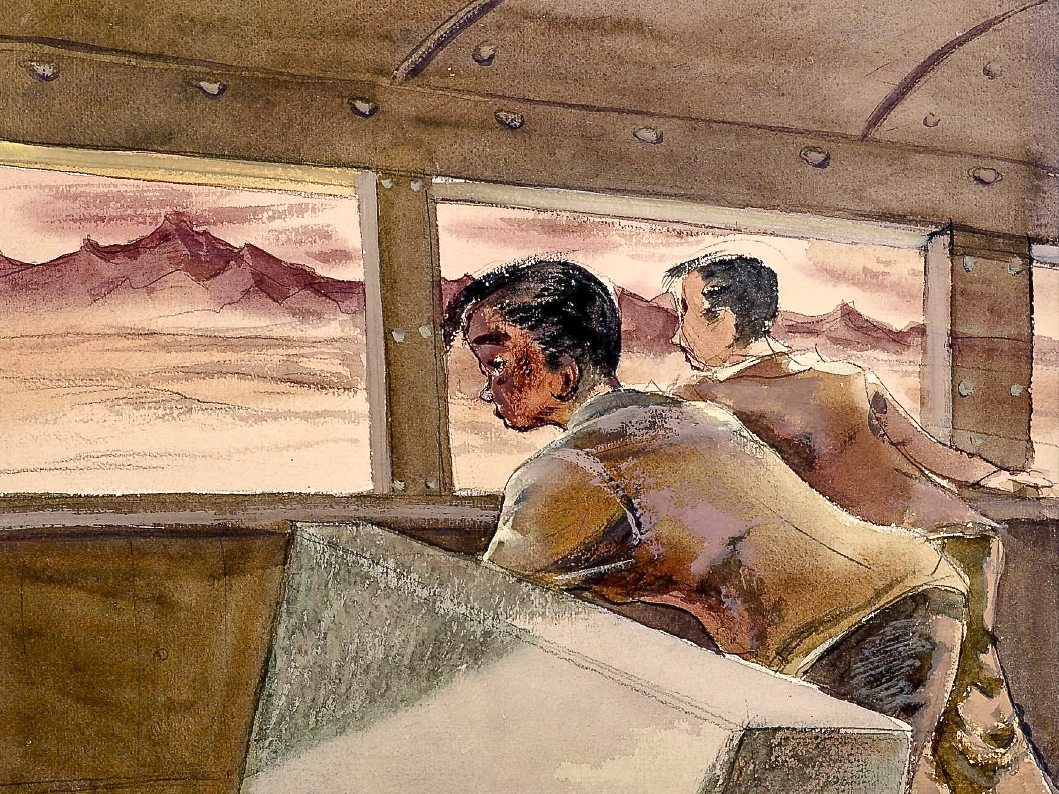

The series starts with the one-way train ride under armed guard into Parker, AZ, arrival in the desolate camp and includes rare images of the turmoil and upheaval of the 1942 Poston strike.

Sogioka recorded “the presence of informers, the beatings, riots, arrests and interrogations — all of these facts of life in the Poston camp,” writes Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, professor emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles.3

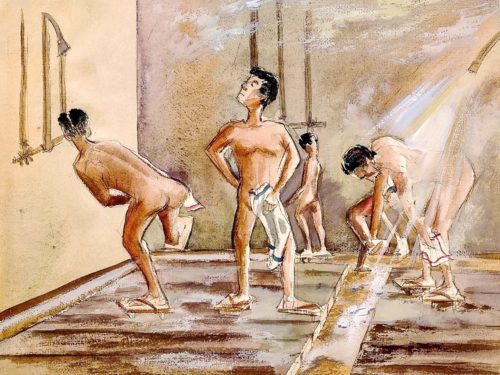

The artist also left behind quick washes of comic relief and caricature. Imprisoned bodies are freely in motion — dancing, brawling, bathing and ready for intimacy in a barrack without privacy. Youthful dissent is seen in a watercolor of two boys who spit at an FBI agent, after he walks by.

“Spitting on the FBI”

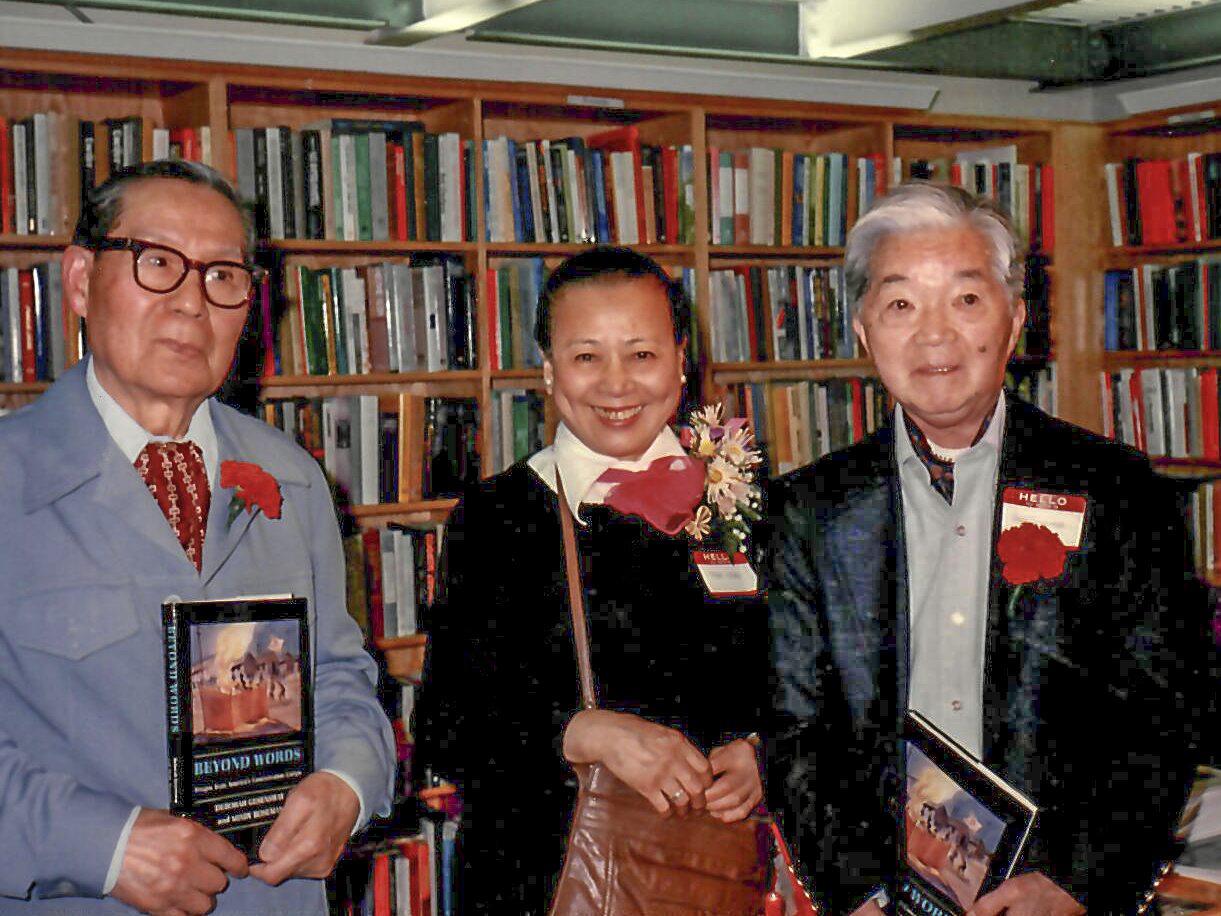

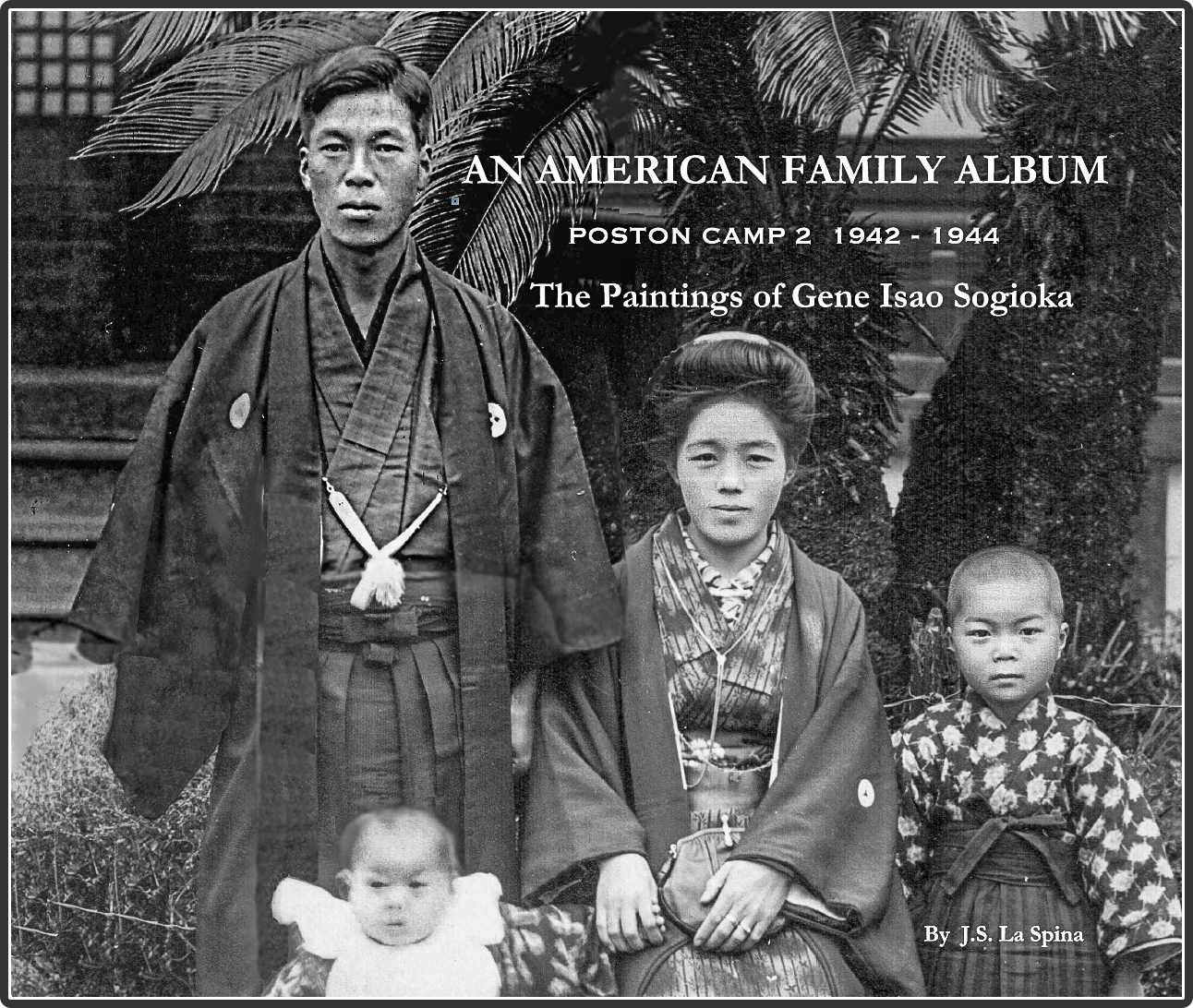

Until now, the full collection has never been seen by the public, but thanks to a book recently published by his daughter, Jean Sogioka La Spina, Gene’s Poston record has been brought together in one place.

In An American Family Album, we can see for the first time the entire series of vivid, storyboard-like images that, remarkably, were not censored despite content described as “not favorable” by a WRA official.4

It’s not clear how Sogioka got away with creating work that countered the official propaganda of the day, especially given that it was done for the governmental Bureau of Sociological Research.

But the project director, Alexander Leighton, a Naval commander, medical doctor and anthropologist, whose aim was to study the impact of mass incarceration on civilians, explained in a 1983 interview that Sogioka’s assignment was “to describe with brush and pigment what the others in the bureau were describing with words.”7

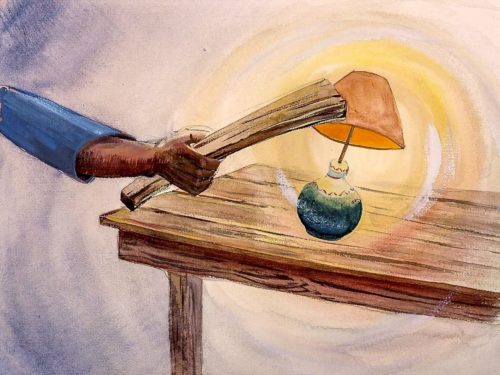

Some paintings show incidents that Sogioka was unlikely to have witnessed, such as stealth night attacks on suspected informers.

According to Mary Higashi, 95, a typist on Leighton’s team, the BSR held regular staff meetings which Gene attended. She said that team members listened to each others’ oral reports and in some cases Gene may have “visualized” events that he did not personally witness.

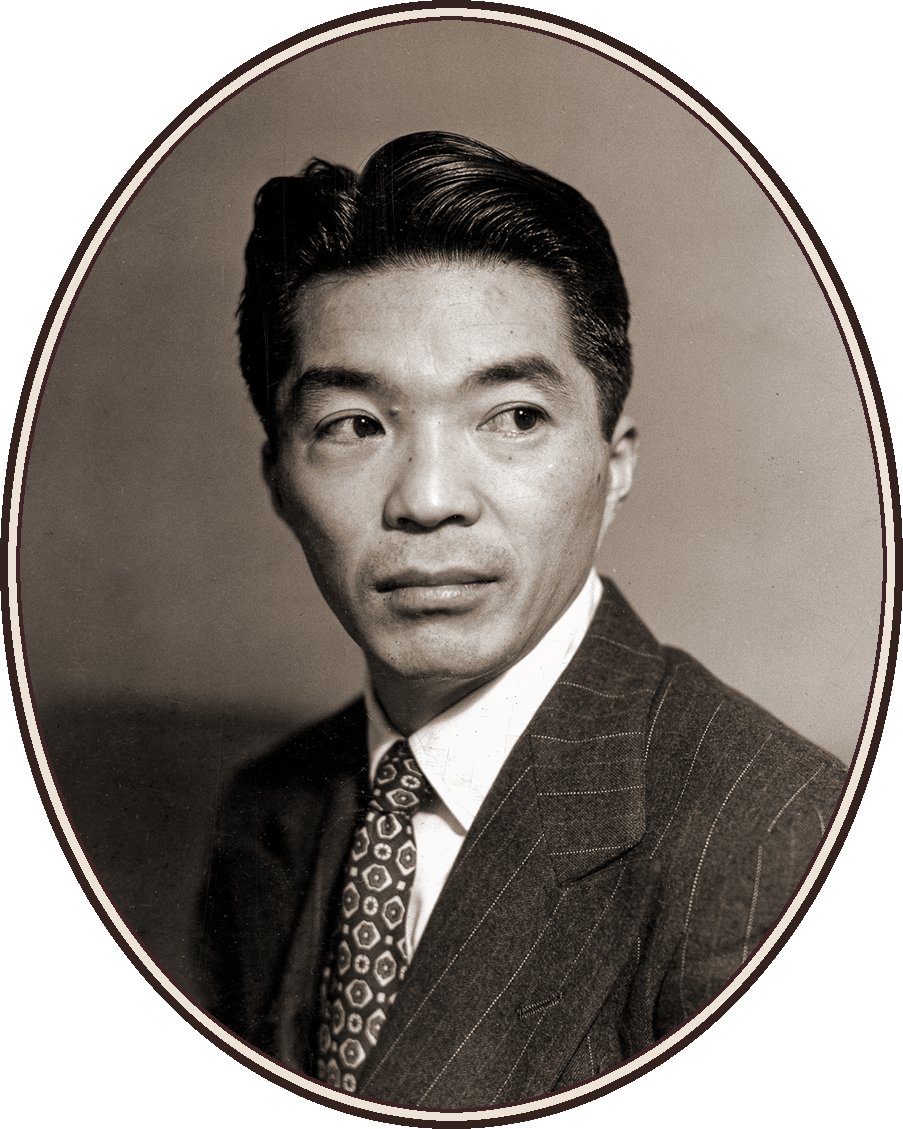

The Artist

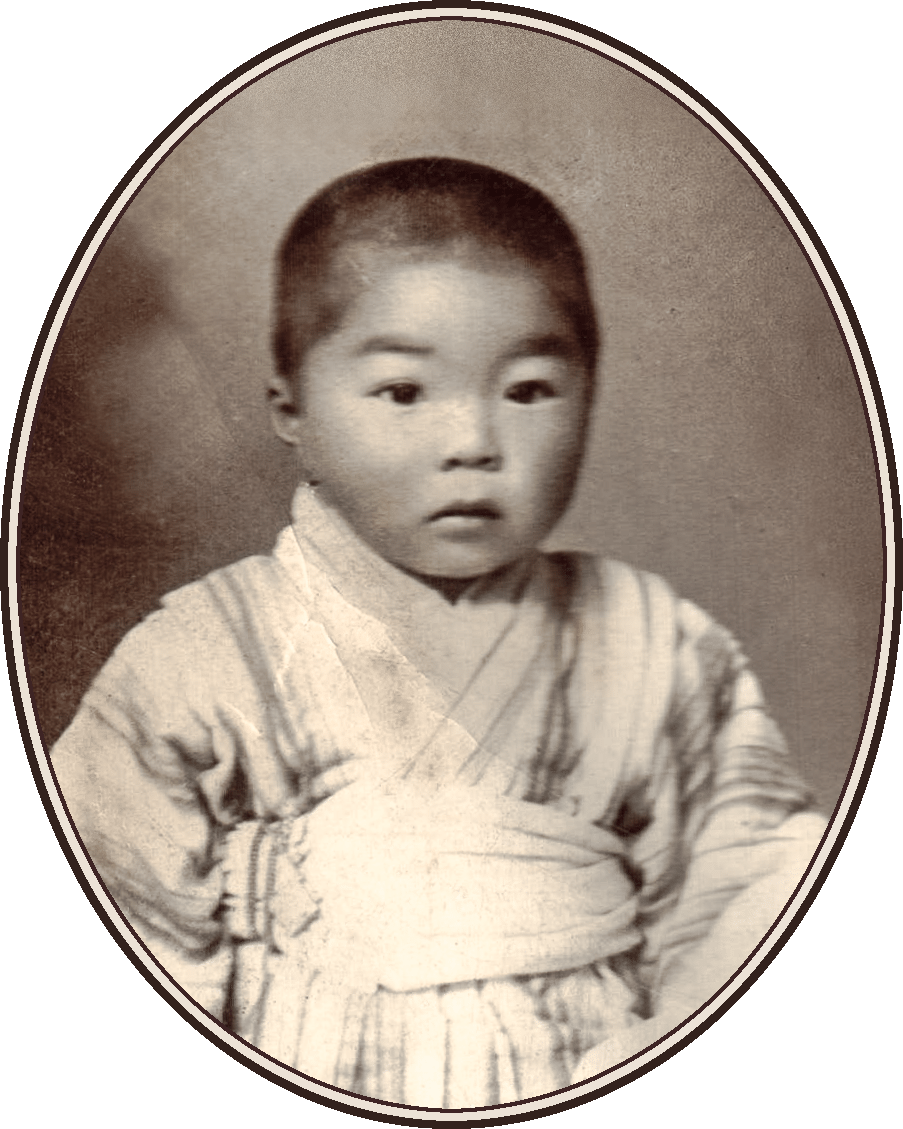

Gene Isao Sogioka was born in Irwindale, CA, in 1914, the eldest son of immigrant farmers in Baldwin Park. Sadakichi and Setsu Sogioka sent him to rural Hiroshima when he was a baby and he spent his childhood and early adolescence there, until age 14.

After returning to Los Angeles, he struggled to catch up at Covina Union High School while helping with farm chores at dawn. He studied at Pomona College for two years but left after racial exclusion from housing and social clubs convinced him that a four-year degree would not lead to a job. He decided to follow his love of art and received a scholarship to attend the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles.

After graduating, Sogioka taught for two years at Scripps College before getting hired by Disney. His salary dropped from $60 a week at Disney to $4.75 a week at Poston.

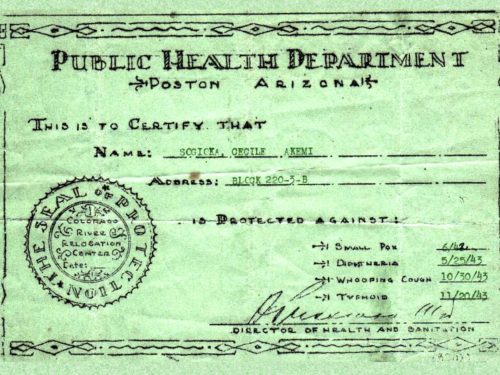

In late 1943, Sogioka was cleared by authorities to leave Poston for New York City, ahead of his wife, Minnie, and their daughter, Cecile, 2. Without a bank account and so malnourished that he was rejected for service by the U.S. military, he eventually settled permanently in the state with his young family and logged years in commercial art, far from the life he once imagined.

An Attic Discovery

In 1980, 35 years after the war ended, the wartime artwork was discovered in upstate New York, rolled up in attic cartons on the campus of Cornell University.

Gene was stunned to learn of their existence after so many decades. Researchers visited him at his home in Larchmont, N.Y., bearing images of the work. “I want to forget about it,” he said at first, emotions welling up. The recovery of the work became the inspiration for the 1987 book, Beyond Words: Images from America’s Concentration Camps, which featured his paintings and the work of 24 other Nisei artists. The discovery became “the height of his senior life,” Jean says. He died the year after the book came out, at age 73.

Jean’s mother and sister died in 2005 — the last members of the immediate family to have lived through the camps — motivating Jean to do “something” with her father’s paintings.

The watercolors had been left to Cornell University by Leighton, but he specified that the copyright remain with the Sogioka family. One day, in her Florida home, Jean was looking at snapshots of her father’s works when she accidentally dropped a stack of prints on the floor.

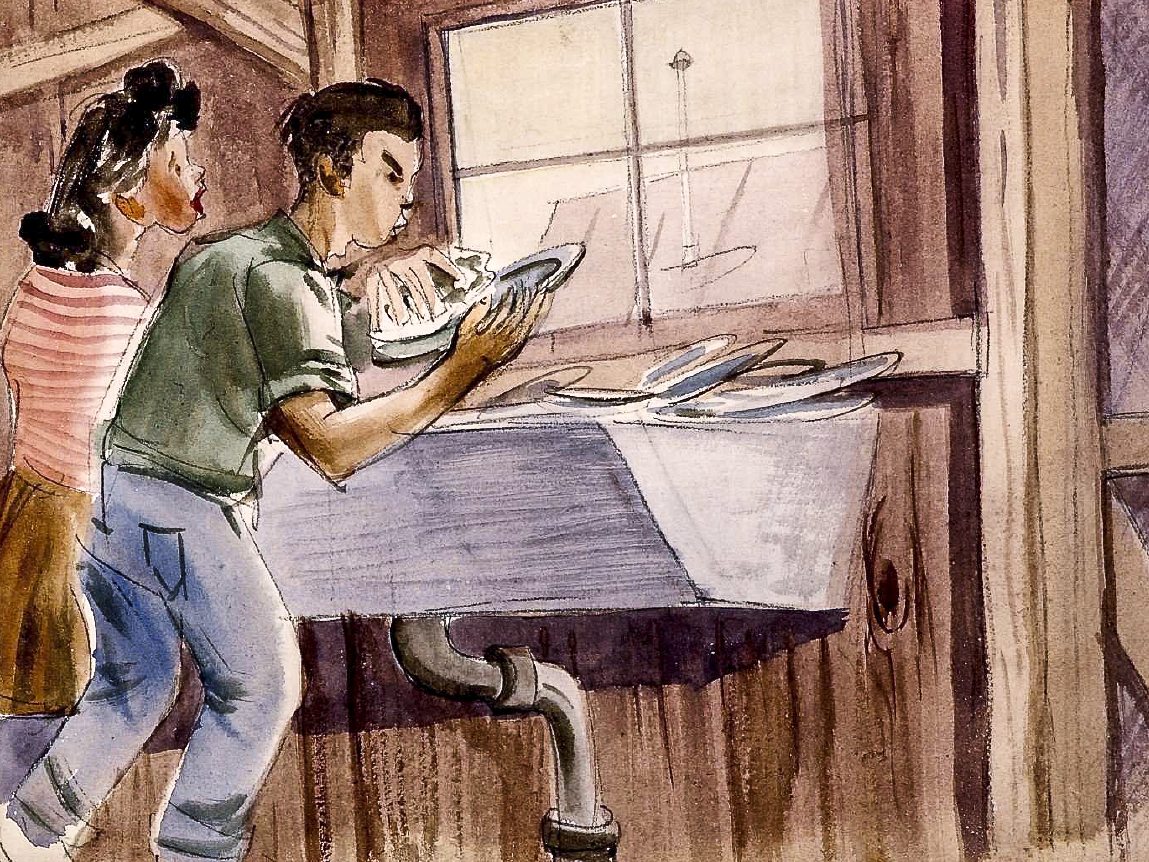

“First Job Helping Her Wash the Dishes”

”As I picked them up, I realized, ‘wait, that looks like dad, and that looks like mom,’ and I realized that he had painted the family in some of these pictures. And that made it more exciting and more personal.”

Finding family in her father’s imagery connected her to a personal past whose ghosts came alive. “It was so meaningful to see my mom sitting there on the train or to see my grandparents, and it became such a puzzle that it consumed me 24-7 to find out who they were. And so I went on an adventure of finding relatives that I knew about but had never met.”

She decided to write a book and spent the next five years immersed in immigration records and family trees, studying the paintings for clues to the history of Poston and her family.

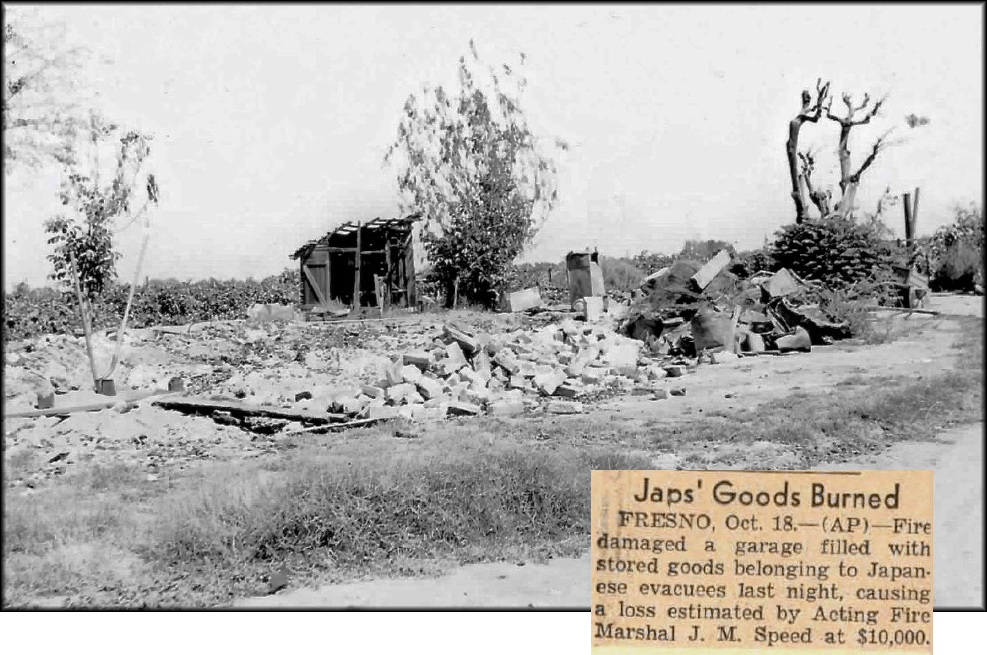

Copyright 1942, The Seattle Times. Courtesy of The Seattle Times.

One of the family’s most harrowing stories has no visual image. Her parents, in their 20s, had led a group of 12 or 13 into a period of hiding in “the canyons” of central California, in order to escape going into the camps. They finally surrendered from exhaustion, dehydration and fear of armed vigilantes. The only survivor of that period, an elderly relative, will not discuss it.

Jean, 70, considers the book her “destiny,” a gift to her father. “I was supposed to do this book and give him his chance to have his show,” she says, the exhibition that he was never able to mount during his lifetime.

It also is an album for her grandchildren, who are one-quarter Japanese and who “really identify with their Asian side.” It’s important for them to know this history.

Photo: Kimiko Marr, 10/31/2017, Tequesta, Florida.

| Sogioka's Paintings | |

|---|---|

| dimensions | 9” x 11” to 15” x 22” |

| material | Watercolor on paper |

| date | June 1942 - Sept. 1943 |

| creator | Gene Isao Sogioka |

| site | Poston (Colorado River Relocation Center) |

| collection | Division of Rare Books and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library |

| Caption photo right | Eisha Leigh Neely, Reference Specialist, and Evan Earle, University Archivist, with Sogioka paintings at Cornell University Library. Photo: Hilary Dorsch Wong. |

13 Watercolors by Gene Sogioka 1942-1943

We are honored to present here a sampling of Gene Sogioka’s camp oeuvre coupled with personal interpretations of the images made by his daughter Jean Sogioka La Spina. The excerpts below are from Jean’s recent book which includes a compilation of her father’s works and Jean’s summary of camp life and her family’s history before, during, and after World War II. The titles for the paintings were written by Jean.

The Train – Isao and Mutsushi See the Desert

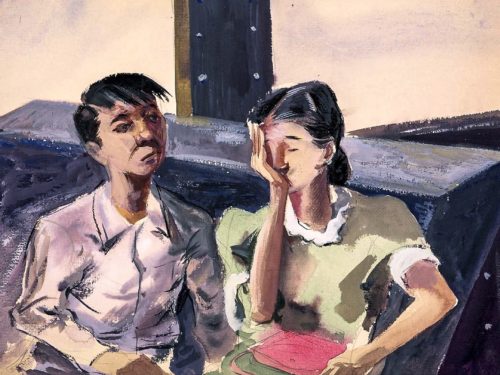

“… as they endure the 30-hour train ride (from Sanger, CA, to Poston) Gene is dressed in a suit. His signature forelock is swept to the right, as he looks out the window with his brother, worrying about their uncertain future.”

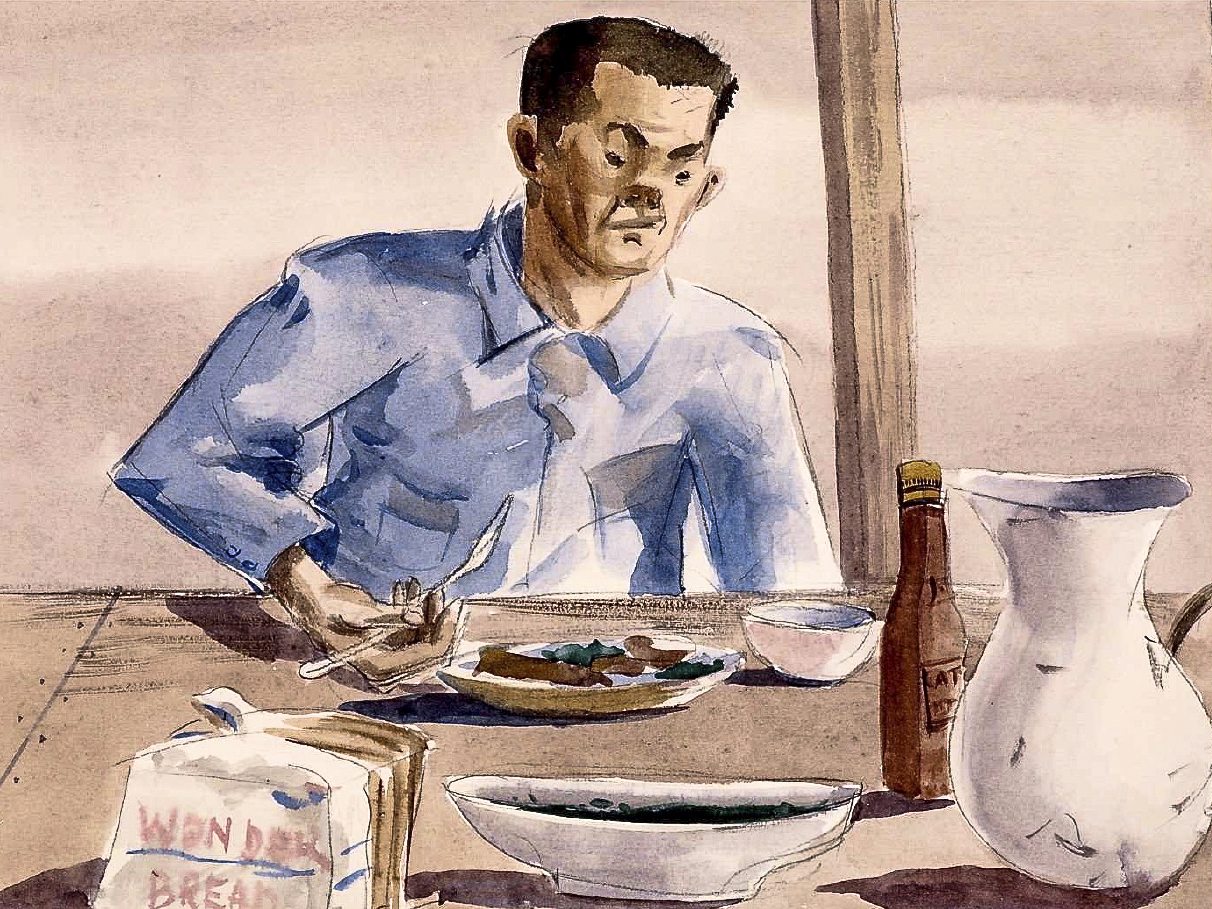

Our First Meal – Not Our Kind of Food

“….an Issei man sits on a bench at a wooden picnic table and grimaces in disgust at the thought of eating hot dogs with catsup on Wonder Bread for his first camp dinner.”

Run to the Women’s Toilet

“… my mother races for the bathroom with arms pumping in a runner’s stride. The women’s communal flush toilets are inconveniently located and fitted with army issue toilet seats designed for soldiers. Mothers with children, the sick and elderly suffer greatly. Small children must be supervised for fear of falling through the seats to land in a raw sewage pit.”

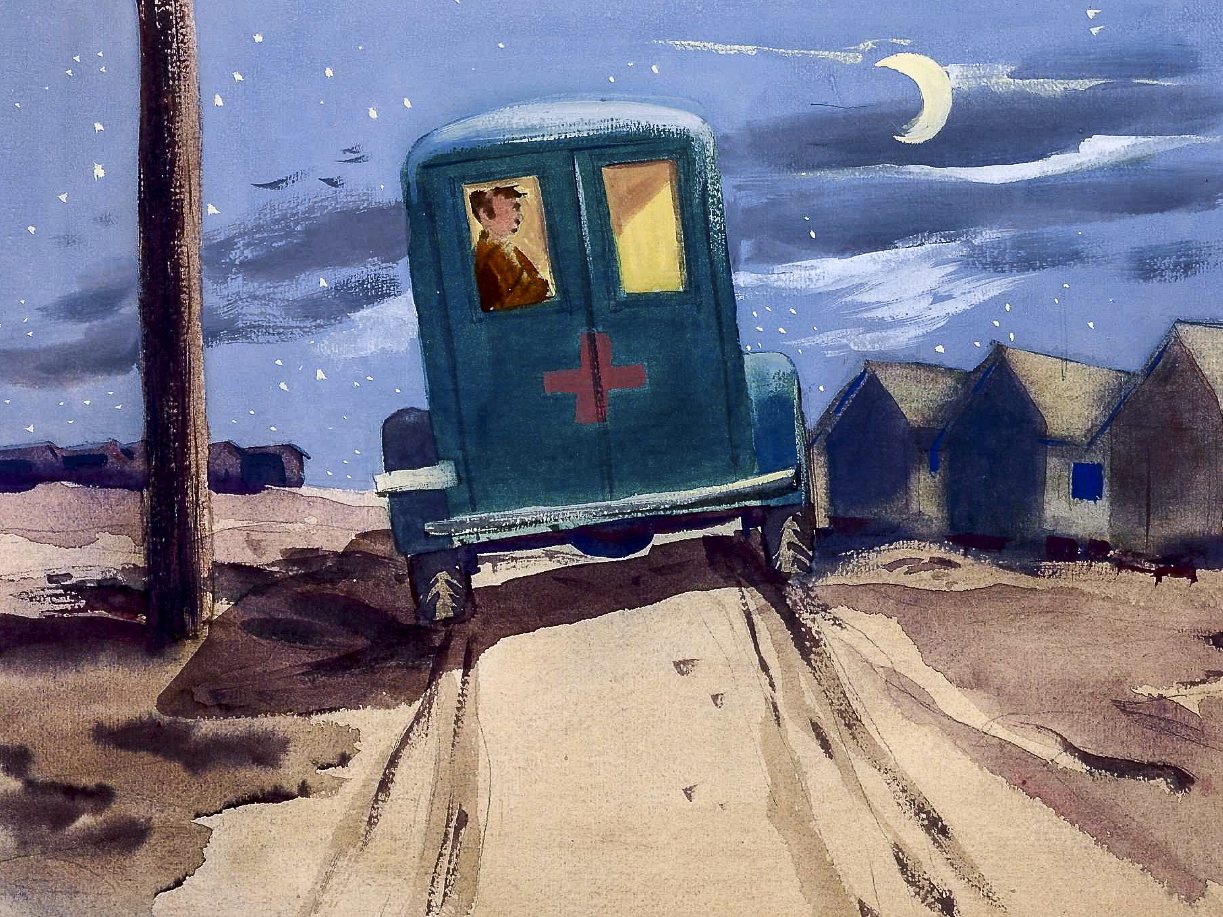

The Ambulance

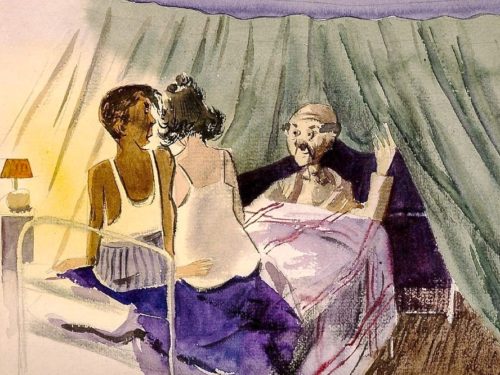

“The doctor arrives by ambulance to transport his patient, a common practice due to the distances between the hospital and the three camps… Poston Hospital provides some basic dental services such as tooth extractions, fillings and general healthcare physicals and immunizations… But the hospital is greatly understaffed and lacks many supplies and equipment to support the large population” (17,814 inmates at its peak in September, 1942, the 3rd largest city in Arizona at the time).9

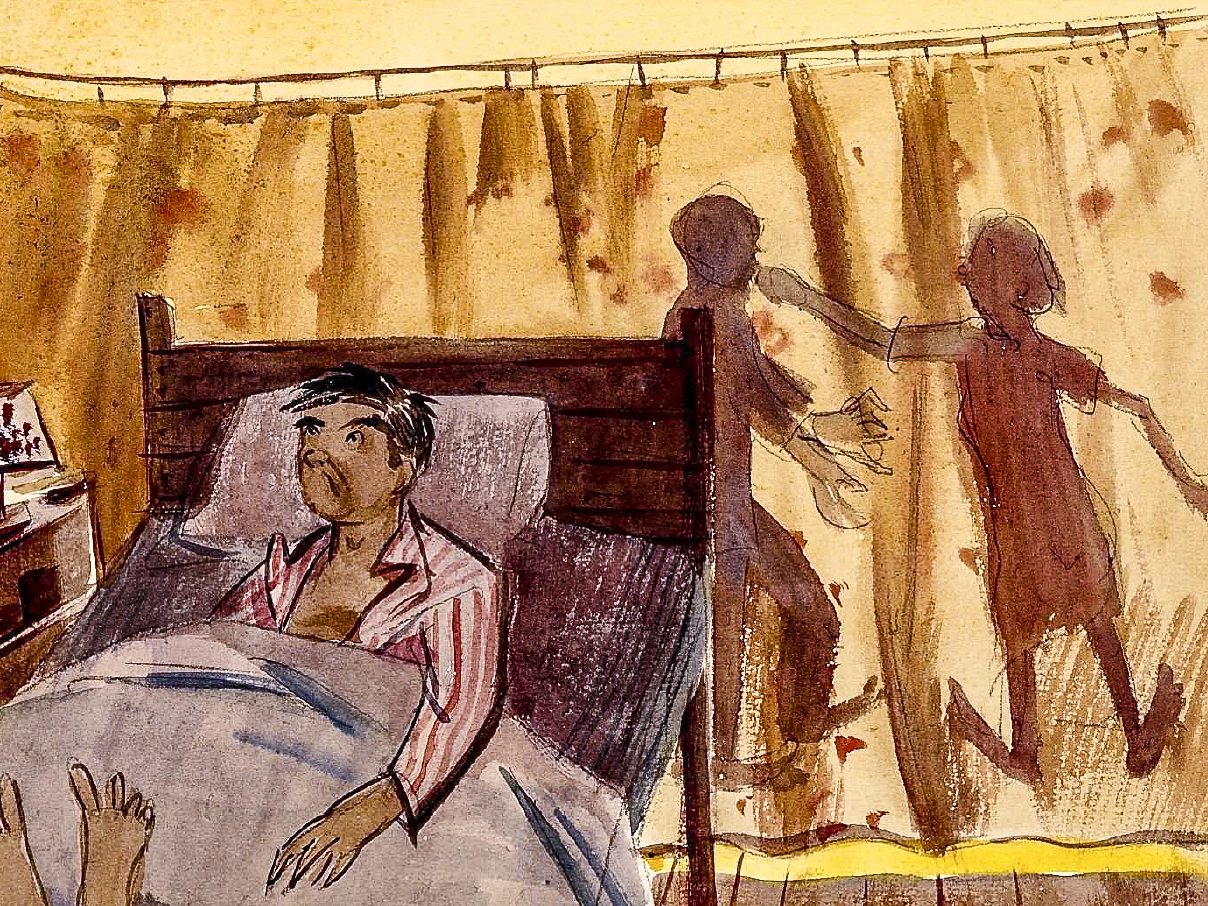

Sleepless Night – Fighting Behind the Curtain

“Loss of privacy and confined living arrangements often divided families and created generational gaps of turmoil. Women, especially mothers found camp life difficult, particularly with respect to feeding, washing, bathing, supervising and protecting their children.”

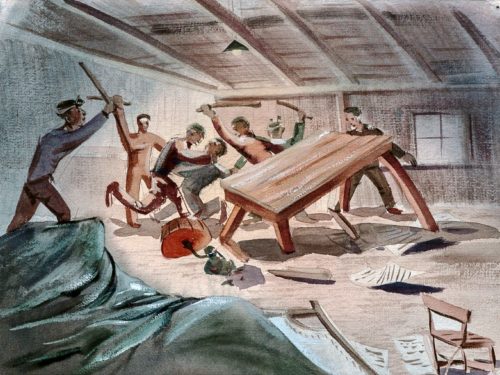

Acts of Violence – the Beating

“Tensions peak when two internees are accused and imprisoned for organizing the beating of an alleged FBI informer. The accused are denied legal representation and the WRA refuses to intervene on their behalf. The Beating conveys the intensity of the raw violence in a smear of red color against a cluster of male bodies pounding down on the suspected informer.”

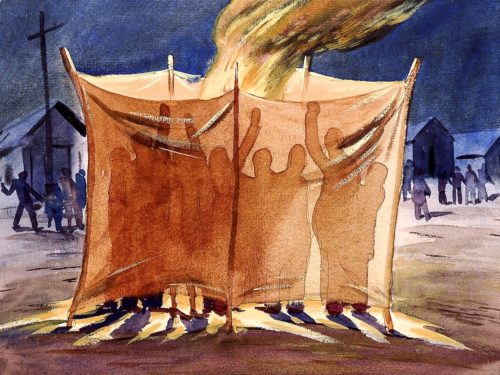

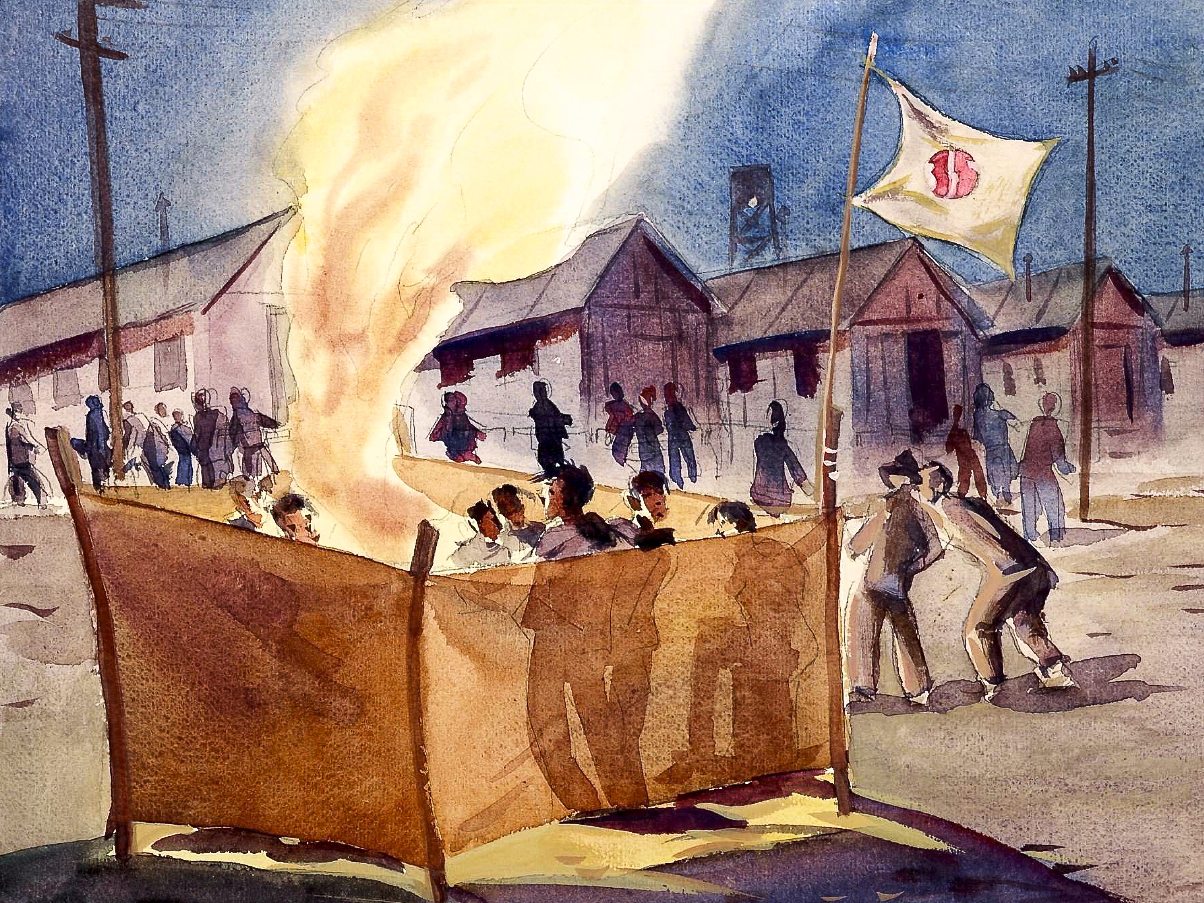

Political Fires of Discontent

“Many supporters of Japan … vent their anger and resistance to authority by initiating a five-day work strike in November of 1942… Groups of supporters gather around fires burning in oil drums to stay warm, as shown in Political Fires of Discontent; figures walk back to their barracks in the gathering darkness while large flames burn brightly within a sheet wrapped enclosure.”

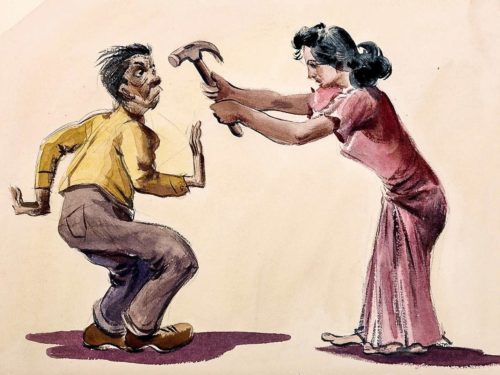

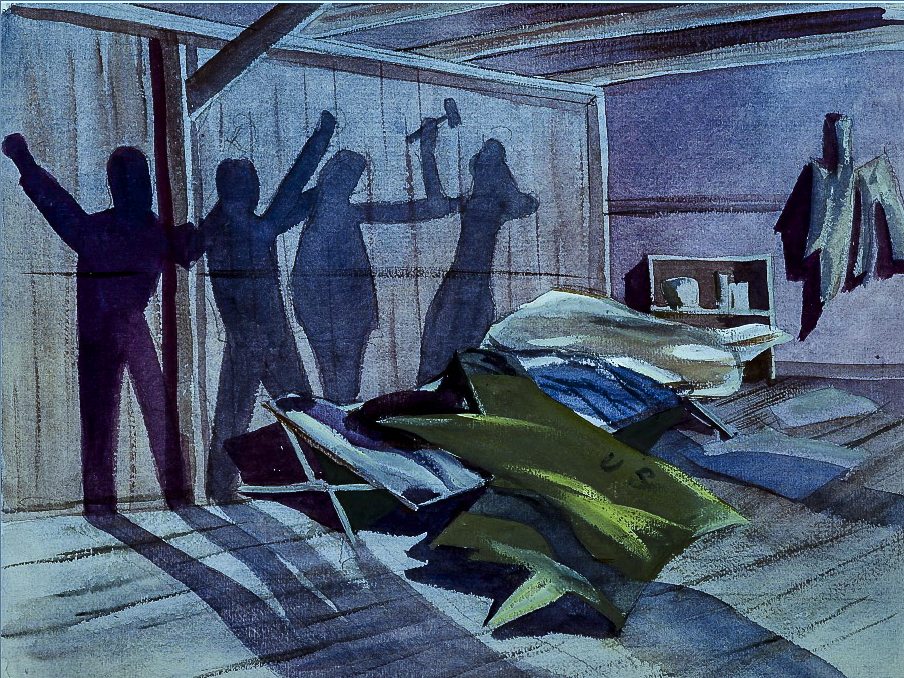

Shadows on the Wall – Camp Violence/Woman with Hammer

“Domestic and gang violence occurs in the camps… A volatile situation is played out in a bedroom apartment –the threatening actions of three men and one female are exploding into violence: one silhouetted figure reaches out to either strangle or push back the hammer wielding woman while two men stand behind him with arms raised to either prevent or join in the attack.”

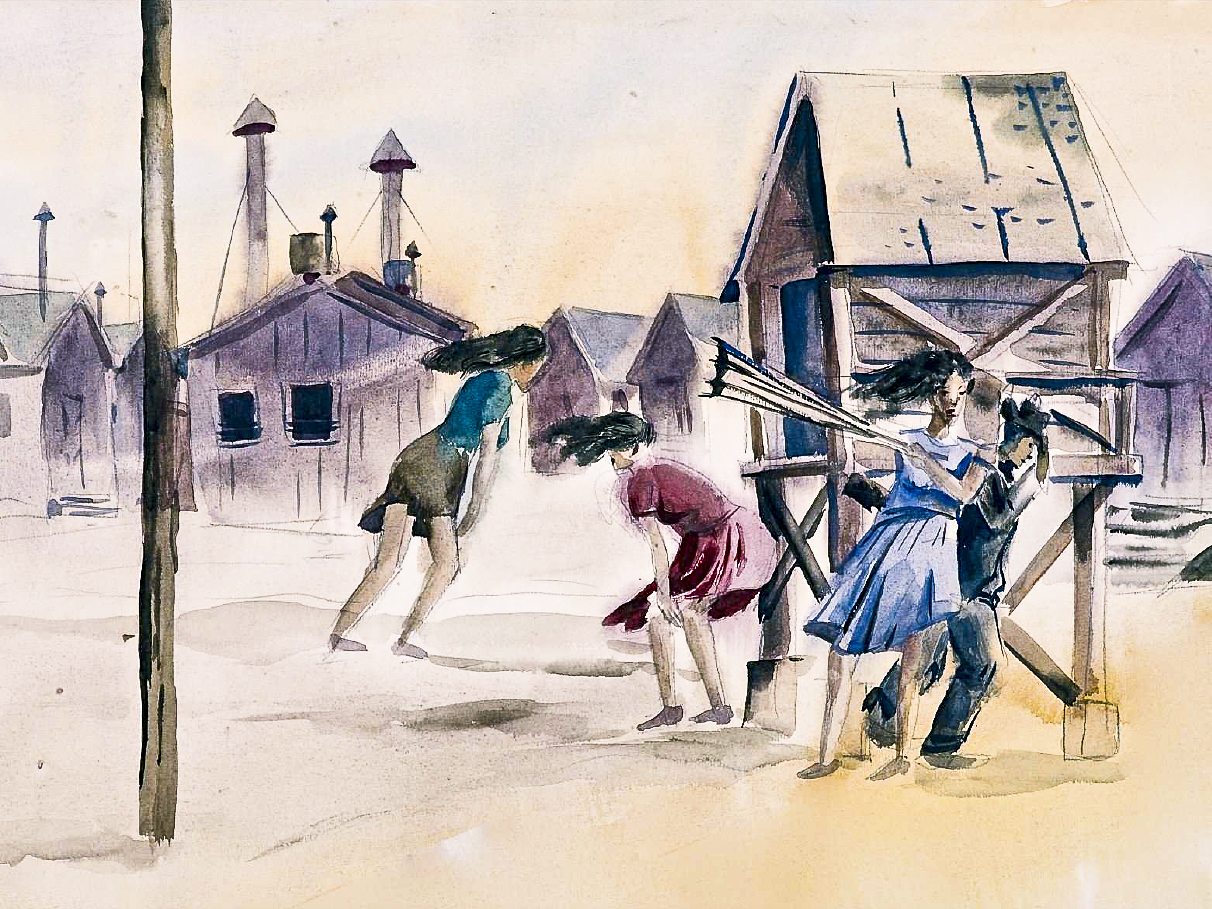

Dust Storm

“Dust is a harsh weather condition of the Sonoran desert… The dust is in everything, entering between floorboard cracks and knotholes, ending up in hair, eyes, mouths, and food.”

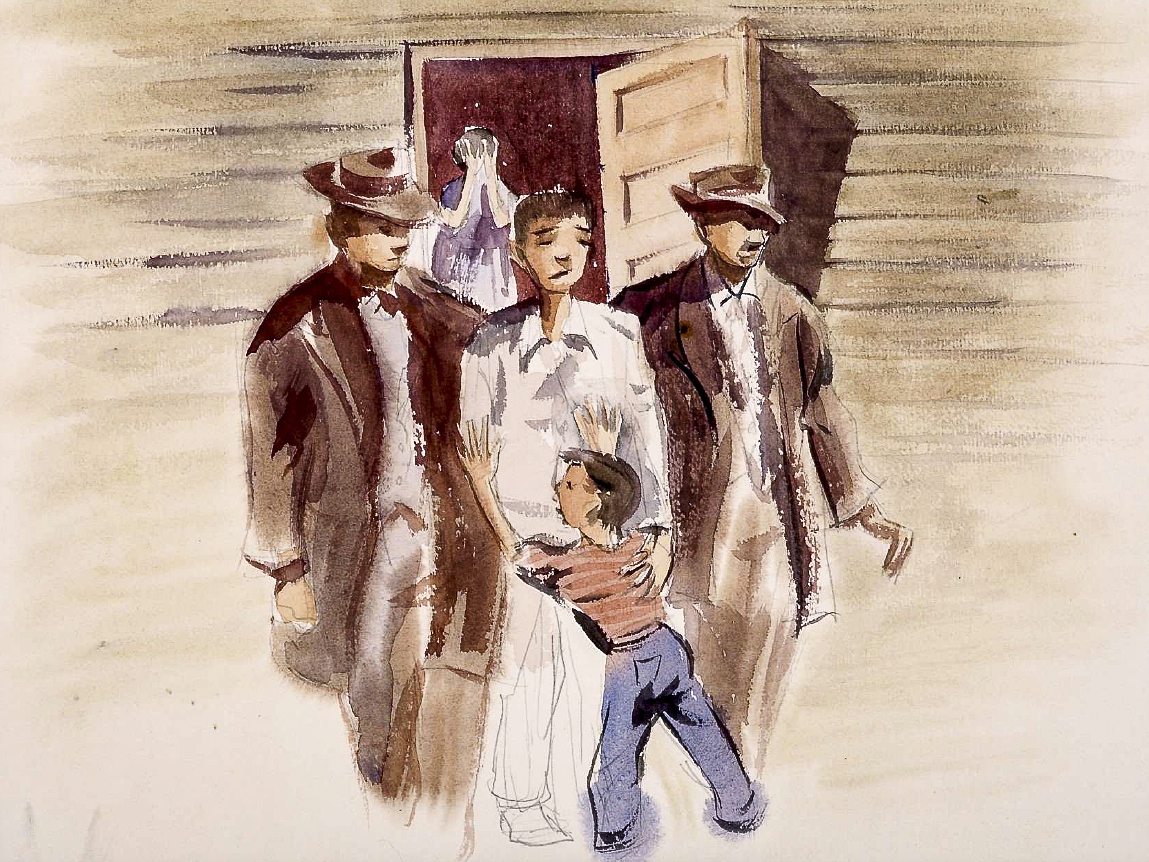

The FBI Took Him Away

“In The FBI Took Him Away, two FBI agents escort a father from his barrack apartment as his young son tearfully embraces him. The son lifts his small arms in an effort to stop the arrest. One agent restrains the sad father by twisting his arm behind and prevents a parting hug for the son. His wife stands at the barrack doorway covering her face in fear and shame. This mother and child may not hear from the father or know when and if the father will be allowed to return to them… Many (of those taken away) are innocent community leaders.”

The Card Game

“Four young Nisei men sit at a table playing cards as their anxious girlfriends watch in the background waiting for a fight to break out. .. A dishwasher earns only $12.00 per month and can easily lose his pay on a single bet, but it is not enough to deter illegal card games and gambling.”

Dancing to the Radio

“Radios and cameras are considered contraband and not allowed in camp, although visiting GI’s on R & R bring cameras and radios for family members… In Dancing to the Radio, two young boys enjoy the music playing on the radio… In 1943, the Nisei kids and my parents enjoy popular music as much as their white peers; it’s the era of energetic big bands like Glenn Miller, Harry James and Benny Goodman.”

Leaving Poston Sepia and White

“Not everyone is happy to depart the camps… my maternal grandfather holds his grandson’s hand and one small suitcase as grandmother wraps a supportive arm around his sagging shoulders and carries her own suitcase in a tableau of sadness. Their faces reflect uncertainty of their return to the outside world; they have lost their home to arson during the war and their lives have changed forever.”

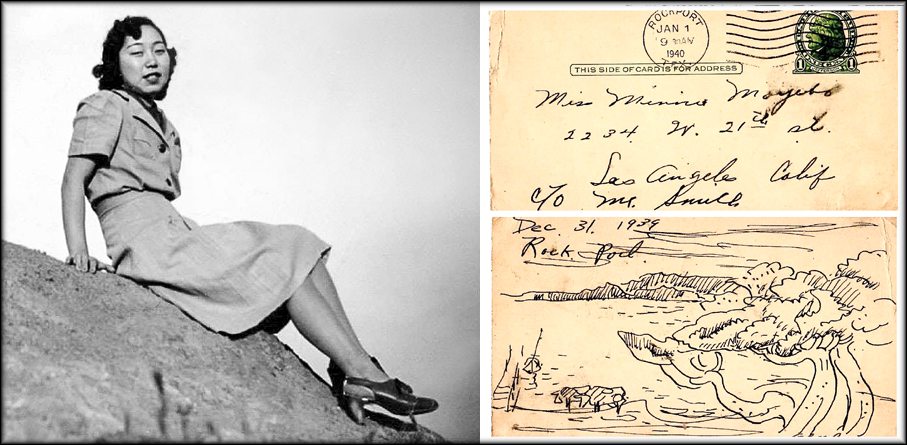

Minnie Mayebo Sogioka

Minnie Mayebo (1919 – 2005), the only daughter of Masato and Ayako Mayebo, immigrants from Hiroshima, met Gene at age 19 on a blind date in Los Angeles. The couple eloped the following year, “breaking from Japanese tradition and her parents’ plans for her arranged marriage to a local farmer,” Jean writes. Photos courtesy of Jean Sogioka La Spina.

Ayako Mayebo, Minnie’s mother, on the family farm in Sanger, before the war.

Older brother, Tom, with harvested vegetables.

Minnie’s first date with Gene took place at a dance at Scripps College in 1939. They had a whirlwind romance and eloped to Las Vegas in 1940.

When Gene traveled around the Southwest, he made sketches and mailed them to Minnie. These were saved among a cache of the couple’s love letters.

After the war, Minnie and Gene raised three daughters in New York: Cecile (photo), Jean, born in 1947, and Alyce (1951). Minnie sent care boxes to relatives in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing. She sewed her daughters’ clothes, made matching outfits for their dolls and taught them to tie-dye using onion skin dyes. When the Sogiokas moved to Westchester County, Minnie decided to take a job so that Gene could paint fulltime. “She was the strength of the whole family,” Jean says. “Most of all, she was compassionate and kind.”

Credits

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

cover images: Gene Sogioka, Kimiko Marr, Clem Albers, David Izu

special thanks to:

Jean Sogioka La Spina, Jimmy La Spina, Mary Kinoshita Higashi, Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, Linda Mayebo, Mindy Roseman, Eisha Leigh Neely, Evan Earle and Hilary Dorsch Wong.

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service,

Japanese American Confinement Sites program