Courtesy of Mitch Homma

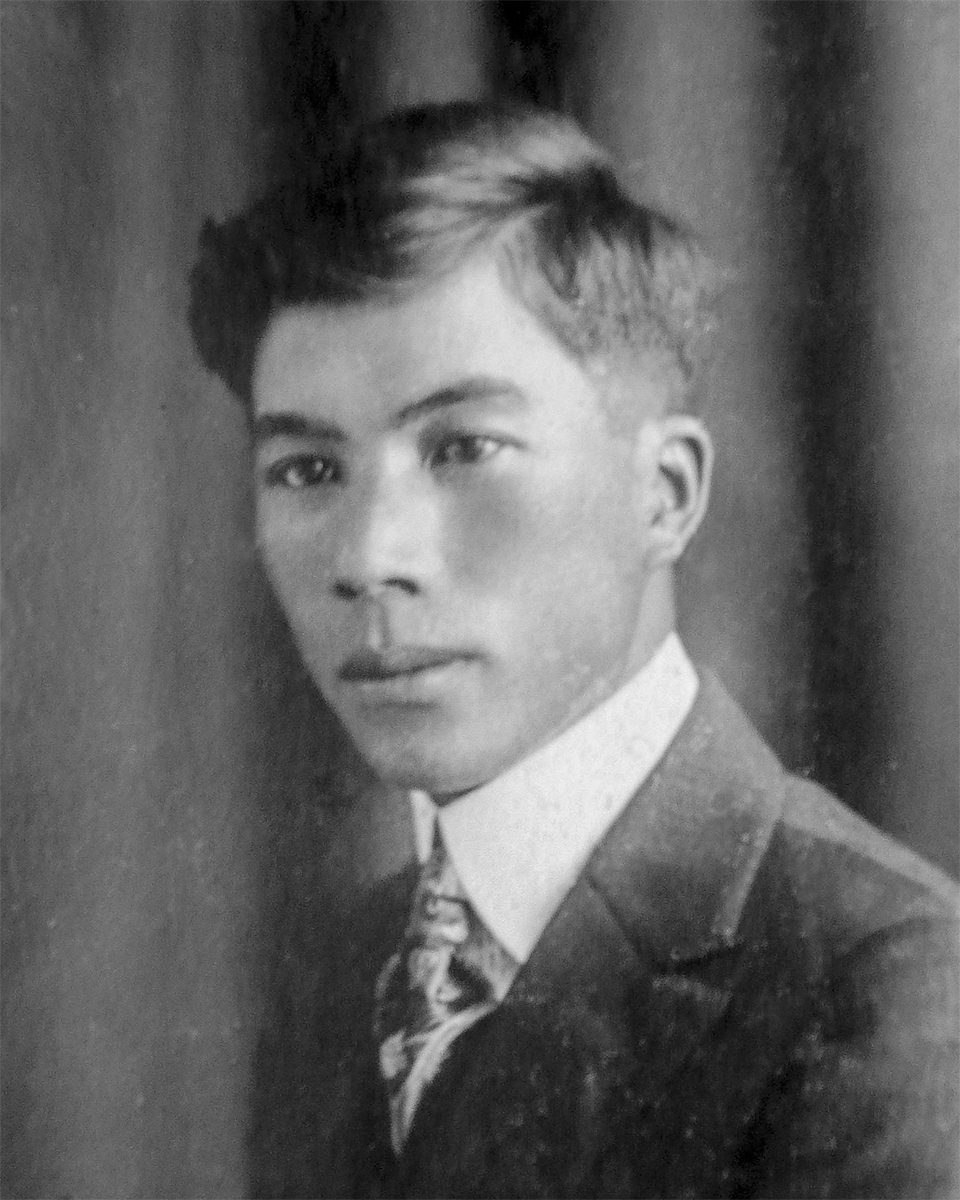

Yorozu Homma was born in Japan in 1895. The Homma family were prosperous landowners in Shizuoka Prefecture who had inherited land from samurai and wished to make it more productive. They looked to the United States as a place of new technologies and Western learning. So at the age of 20, Yorozu arrived in Los Angeles, sent by his family to study greenhouse technologies.

Yorozu had been in Los Angeles for 27 years and was running a floral business when he and his wife, Shigee, were swept up in the mass eviction of Japanese Americans from the West Coast following the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

They found themselves behind barbed wire in Heart Mountain, Wyoming, one of ten WRA concentration camps hastily constructed to house tens of thousands of innocent men, women and children uprooted from their homes.

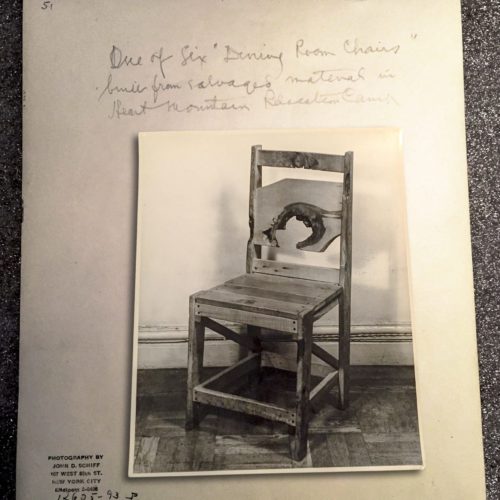

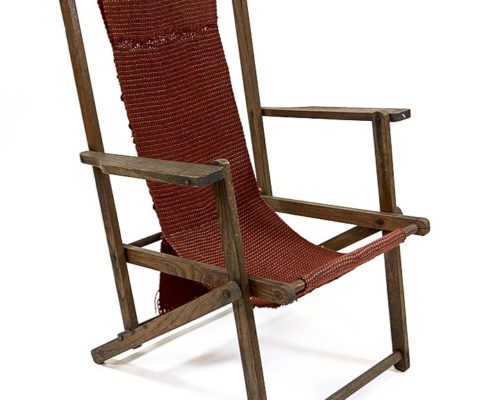

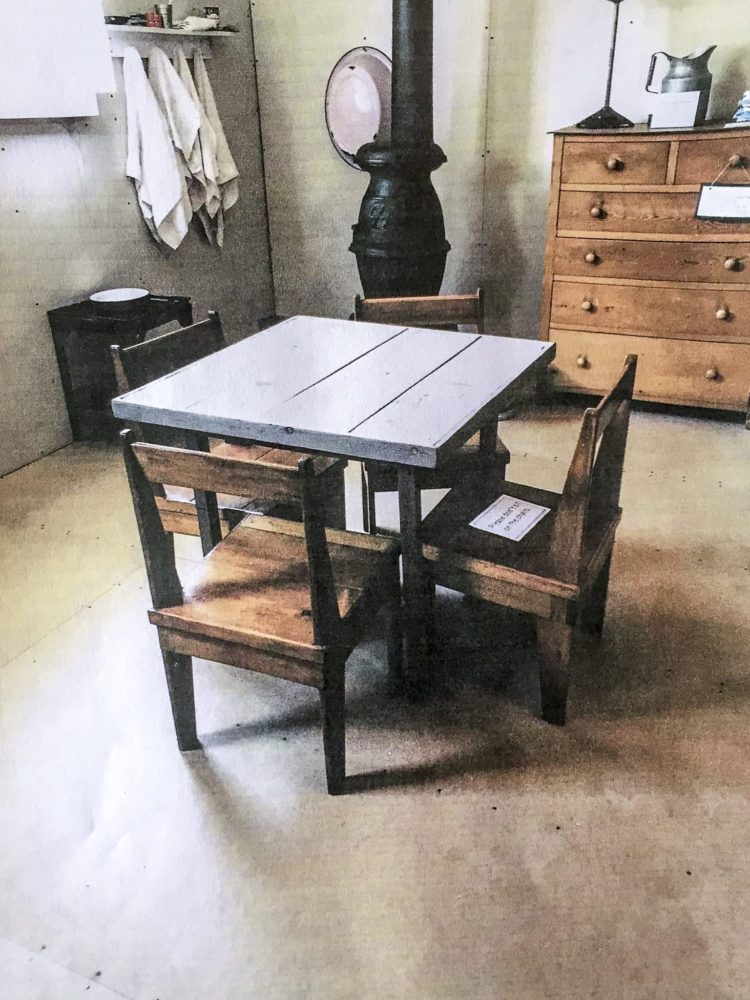

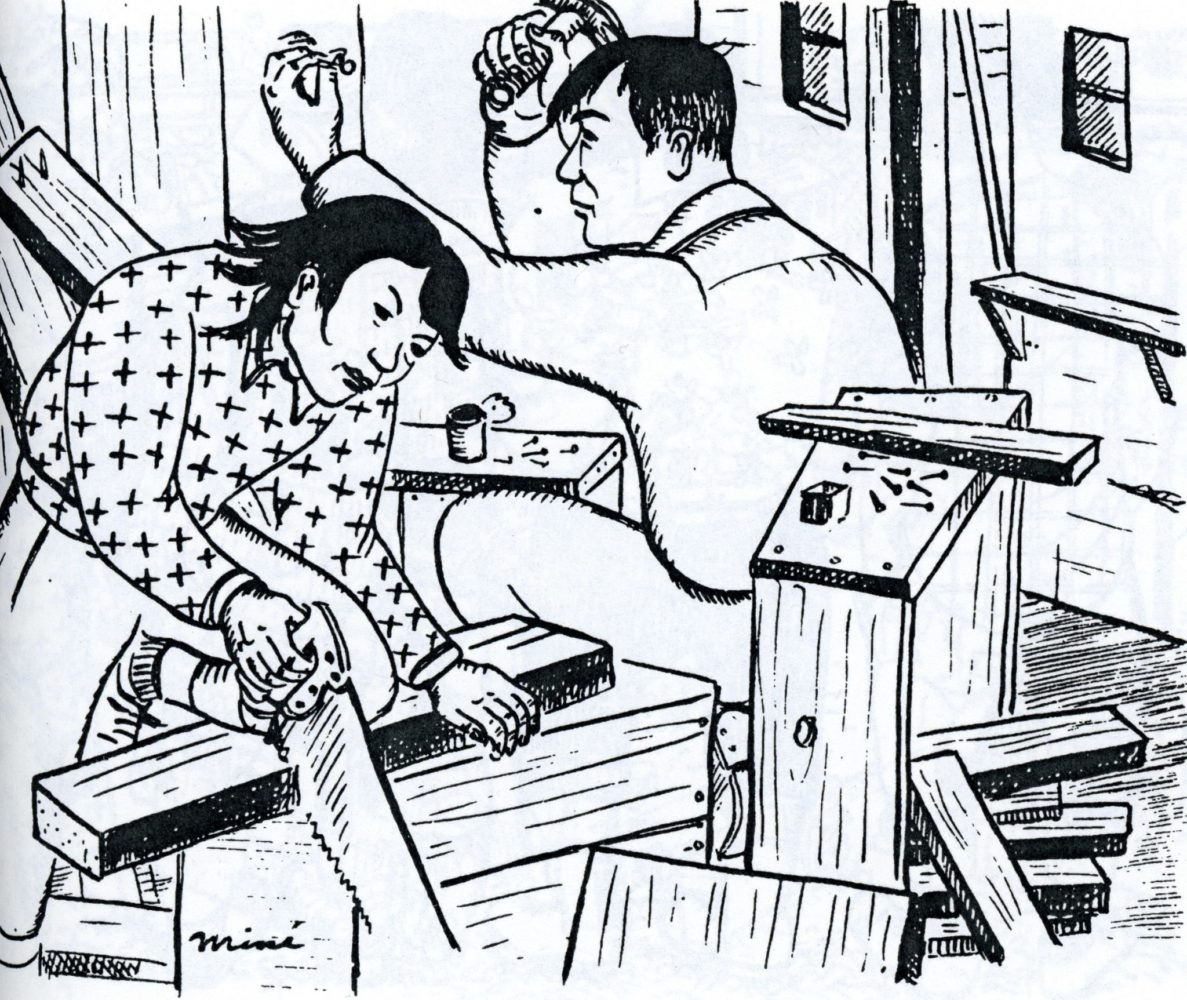

In the flimsy barracks of Heart Mountain, no furniture was provided, save for a cot and mattress. So Yorozu, like many, constructed a chair from scrap lumber.

The chair was simple but its back caught the eye — a slab of wood with a large, round knothole. The ragged opening would have been seen as a flaw by most people, but Yorozu honored the imperfection: he placed it directly in the middle of the chairback.

By highlighting the wood’s irregularity, Yorozu gave an otherwise plain chair a distinctive character, expressive of the sympathy in his native Japan for natural forms. This special detail may have been why the chair ultimately survived.

The Collector and the Chair

In the fall of 1945, Yorozu, in his fourth year of captivity, heard that a collector from New York City liked his scrap-lumber chair.

Allen H. Eaton, the collector and scholar, was in the midst of traveling to five of the camps in order to document the crafts that imprisoned people were making, mostly from salvaged materials. He was taking photographs, collecting examples and meeting artisans.1

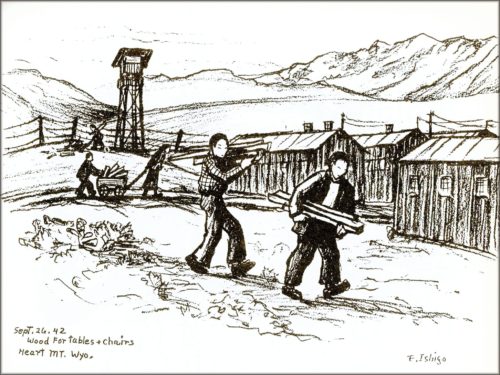

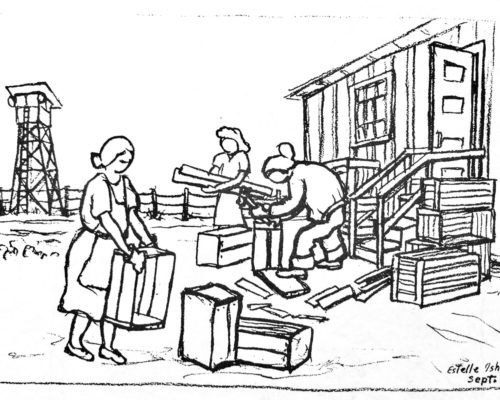

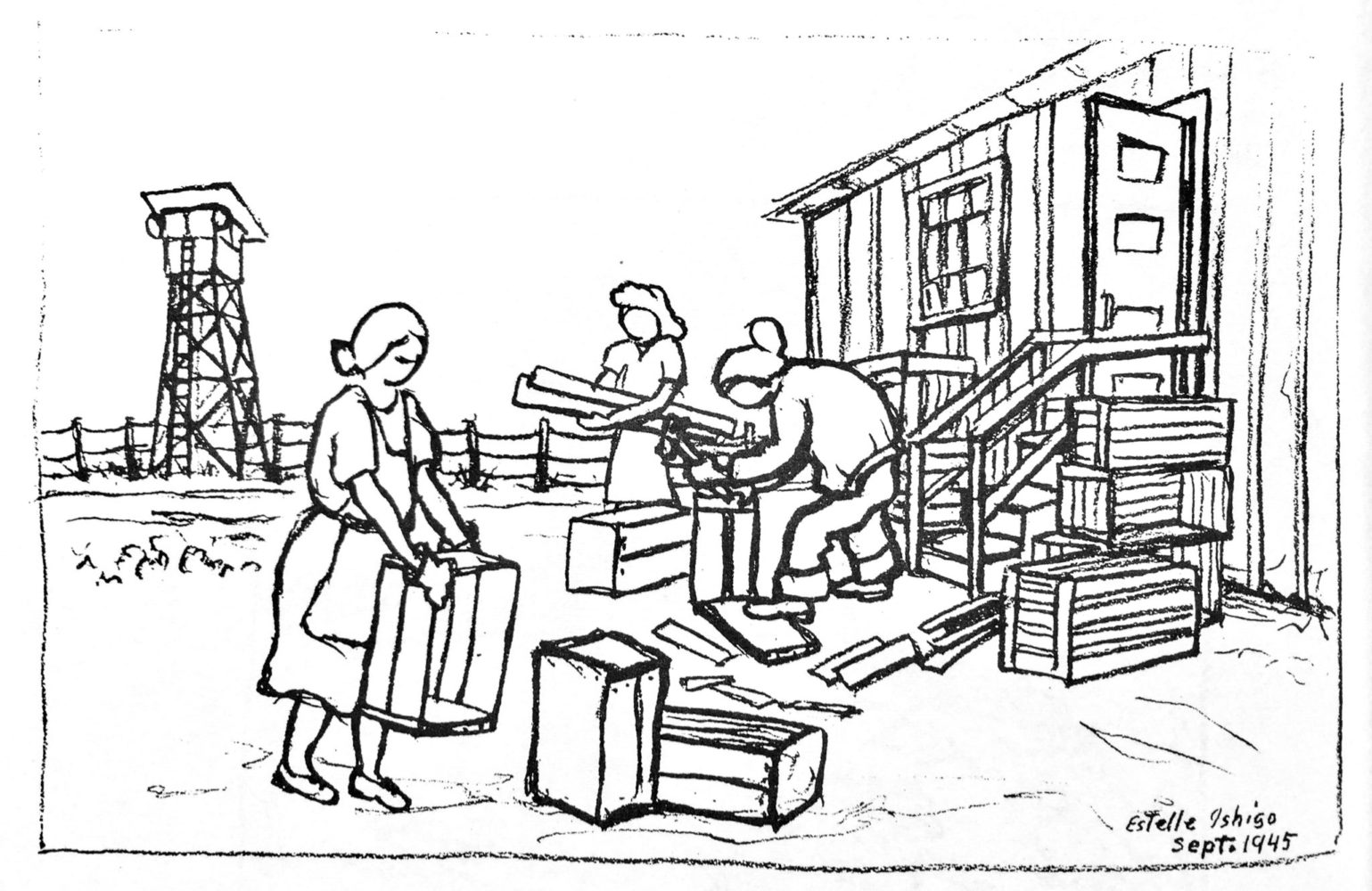

During a visit to Heart Mountain in the fall of 1945, just as the camps were closing, he worked closely with Estelle Ishigo, an inmate and an artist there whom he had hired to help him.

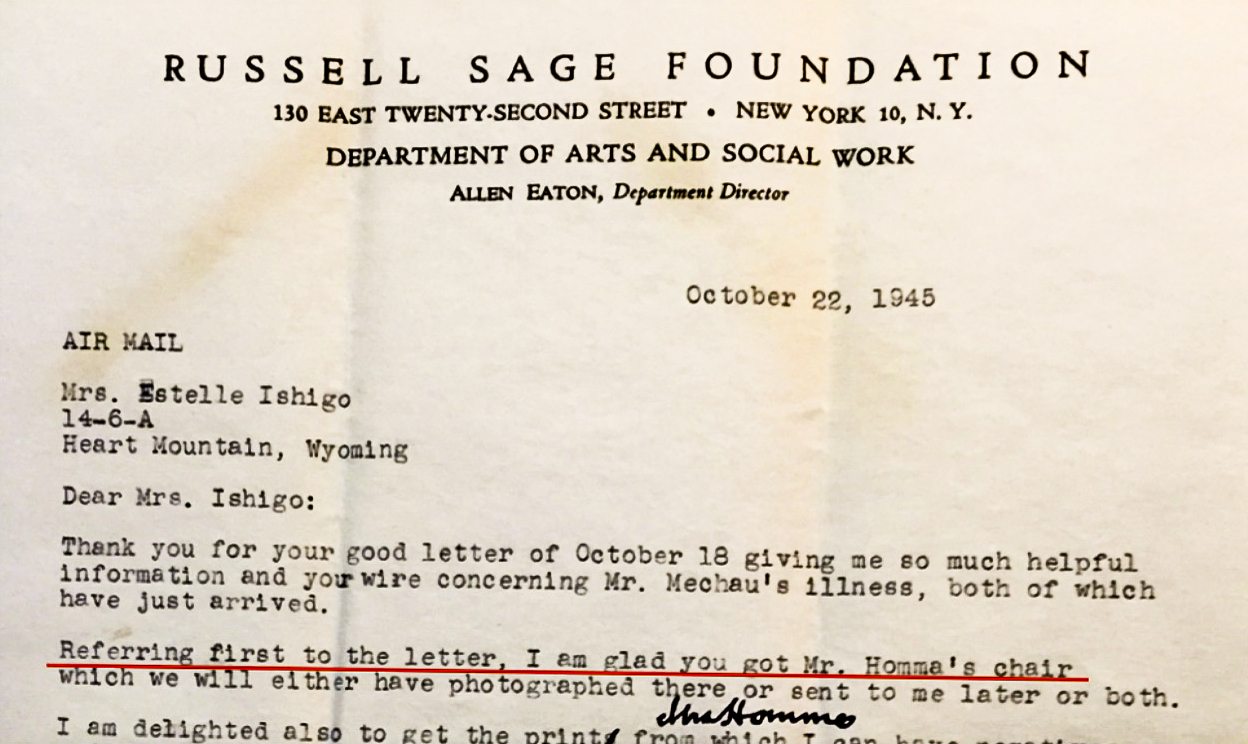

After he saw Yorozu’s chair, Eaton wrote to Estelle from New York.2

Oct. 4: “Did Mr. Homma leave one of his chairs — the one I wanted photographed and told him I would be happy to buy it.”

Oct. 22: “I am glad you got Mr. Homma’s chair which we will either have photographed there or sent to me later or both.”

Nov. 3: “…all the other things sound very interesting, especially Mr. Homma’s chair….”

Ishigo scribbled notes related to her work for Eaton in a small memo book. One entry concerned Yorozu: “chair – Homma $2.00.”

The note is on a page that lists other items with prices. The entries include $1.50 for “photo – Homma,” “dollpin – Murakami 0.25” and “trip to Cody 0.48.”3

Could the note regarding the chair be taken to mean that Yorozu was paid $2.00 for it? In the absence of additional supporting evidence, we can’t know for certain.

In any case, a deal was done and the chair from Block 17-15-A at Heart Mountain was shipped from Wyoming to New York City in early November, 1945.

After the war, Yorozu and Shigee moved back to Japan permanently. They adopted a child and lived in Shizuoka for the rest of their lives.

The Homma chair disappeared from memory.

The Chair up for Auction

Seventy years later, in the spring of 2015, Yorozu’s chair resurfaced online and on the glossy pages of a New Jersey auction catalogue. Displayed on a full page, a color photograph of Yorozu’s creation was grandly described as a camp “Dining Chair.”

It was slated to be sold by Rago Arts and Auction. Yorozu’s name was not listed and the item’s provenance was listed as “Private collection, Connecticut.”7

The “private collection,” located in affluent Greenwich, Connecticut, was that of a businessman who had inherited the chair and many of Eaton’s collections from his father, a contractor for one of Eaton’s daughters. When the daughter died, she bequeathed her father’s collections to the contractor.9

Approximately 450 items that Eaton collected from the camps were being publicized as “material that rarely comes on the market.”10 Auctioneer David Rago estimated the chair’s value at $1,000 but strong interest indicated the final price would go higher.

A social media protest against profiteering from camp artifacts, however, helped stop the sale.

Crafts created in the camps “are not pieces of art meant to decorate a private collection,” wrote Rev. Bob Oshita of the Buddhist Church of Sacramento, on a Facebook page that went viral.

“They are deep and quiet expressions of the hope and despair felt by a people enduring the trauma of racism, hatred and fear. What you are planning to sell should be part of our shared social conscience…and not viewed as simply art for display.”11

The threat of legal action and a celebrity’s intervention led to the cancellation of the auction.12 The Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles eventually acquired all the items.

The Homma chair is now preserved at the museum, only a 30-minute drive from where Yorozu and Shigee once lived near Hollywood.

According to Eaton’s notes, the chair was originally part of a set of six. It is not known what happened to the other five.

| The Homma Chair | |

|---|---|

| dimensions | 36" x 16" x 16" |

| material | scrap lumber |

| date | c 1942 - 1945 |

| creator | Yorozu Homma |

| site | Heart Mountain, WY |

| provenance | Allen H. Eaton |

| collection | Japanese American National Museum |

| Photo caption right: Photo of chair in New York City by John Schiff. Eaton's handwritten notes are on photo back. Photo courtesy JANM. | |

Homma Family Photos

Kyushiro and Yorozu

Kyushiro Homma (left) followed his older brother, Yorozu, to Los Angeles in 1917. He graduated from Hollywood High School in 1924 and from USC dental school in 1929. He established a thriving dental practice in Westwood and counted Hollywood stars such as Shirley Temple among his patients.

Before the forced removal, Kyushiro drained his garden koi pond in Sawtelle and lit a bonfire in it, burning the personal papers and belongings that he couldn’t take with him. Two years later, he died at the Amache, Colorado, camp of a stroke and heart attack. Photo courtesy Mitch Homma.

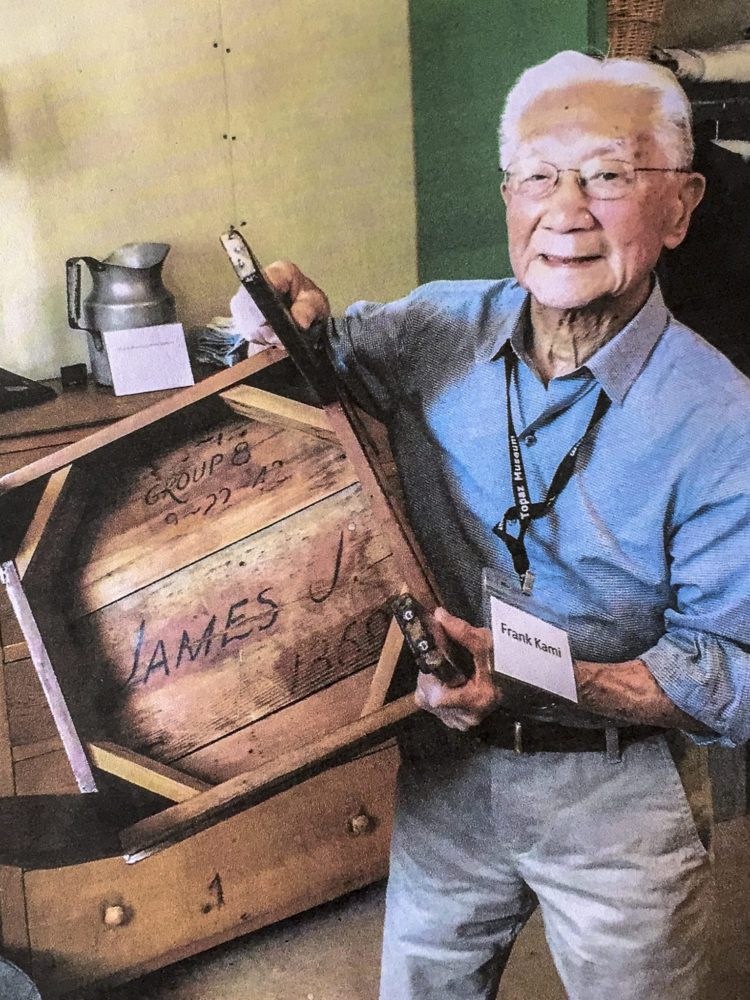

Box made by Yorozu

Yorozu began to carve a box from salvaged wood at Heart Mountain in January, 1944. Eight months later, it was used to collect “koden” incense money at Kyushiro’s funeral at the Amache, Colorado, concentration camp. Family members believe that the tree on the lid recalls the cherry tree planted in Japan when Kyushiro emigrated to the U.S. The trunk of the tree appears to be severed or its growth stunted. Dimensions: 7.5″ x 5.5″ x 3.5″. Photo courtesy Mitch Homma.

Shigee at Heart Mountain

Shigee Homma, Yorozu’s wife, was a popular flower arranging teacher in Los Angeles before the war. She restarted her classes at the preliminary prison camp in Pomona, California, and continued teaching at Heart Mountain, enrolling 500 students in her first year.

In her last year of confinement, she taught 100 children aged eight to 12, who learned to make artificial flowers out of wire and paper. In the photo, Shigee stands before a display of the “Homma Floral Designing School Exhibition at Heart Mountain High School, July 16-18, 1944.” Photo courtesy Japanese American National Museum.

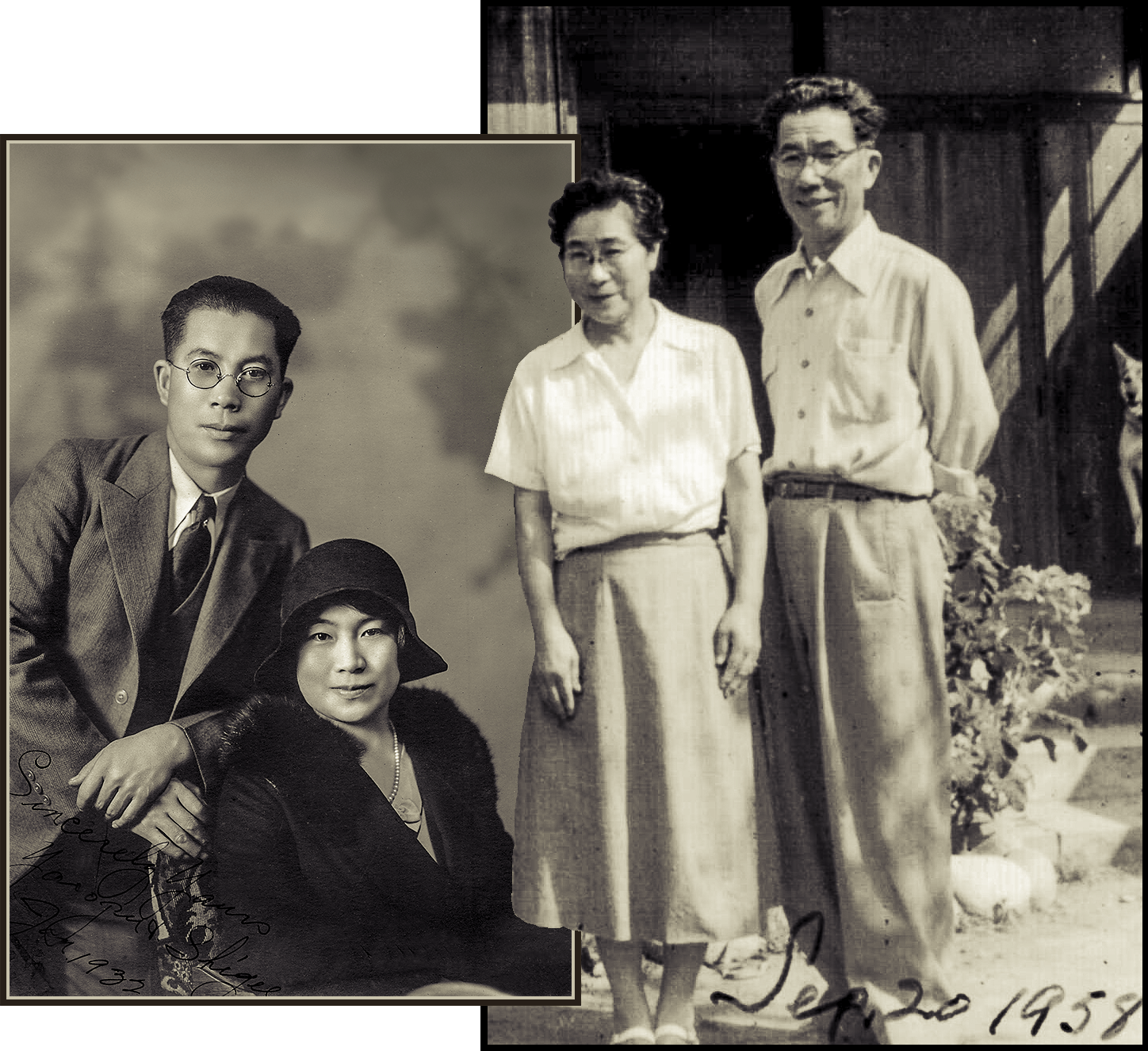

Prewar and postwar

Photo (left side) shows Yorozu and Shigee in 1932. They lived on Surry Street in Los Angeles in 1930 and on North Virgil Ave., in 1940. After the war, they returned to Japan. Right side shows them in Shizuoka in 1958. Yorozu continued his study of plants and seeds, attracting inquiries from a Cornell University professor. Seed specimens were donated to a research collection in the U.S. Photo courtesy Mitch Homma. Photo illustration by David Izu.

Masahiko and Kuni Wada

The extended Homma family was torn apart by the military removal orders. Old and young were sent to detention camps in Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas and Wyoming.

Masahiko (left) and Kuni Wada were Kyushiro Homma’s in-laws. They were Baptist missionaries to the U.S. and were arrested by the FBI at their church, the First Baptist Church of Pomona, in southern California, in March, 1942. Husband and wife were separated and sent to different Department of Justice internment camps for enemy aliens. Photo courtesy Mitch Homma.

Credits

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Special thanks to:

Mitch Homma, Kumi Hasegawa, Bacon Sakatani, Rev. Bob Oshita, Frank Kami, Henry Kaku, Dennis Fujita, Ryan Yokota, Japanese American Service Committee, UCLA Library Special Collections and the Japanese American National Museum.

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service,

Japanese American Confinement Sites program