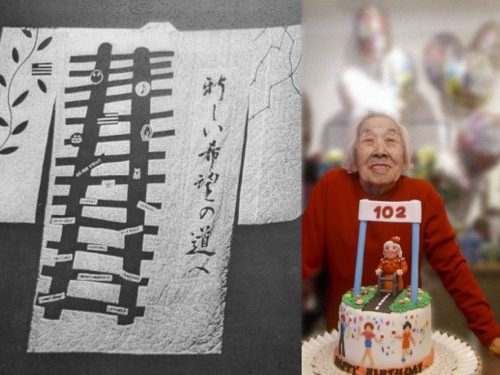

On his birthday, Kiyoshi Ina said hello to his Facebook friends.

“Born December 3, 1942, in an American Concentration Camp! Yes, today is my 75th birthday, thank you for the birthday wishes!

“Sometimes I think I’m lucky to be alive. My mother had a very difficult pregnancy with me. She had to endure the evacuation of all Japanese along the western coast of the U.S.A. while pregnant with me.

“They were sent to a makeshift camp at Tanforan Race Track in San Bruno, CA, to sleep in the nasty, smelly horse stalls. She suffered from morning sickness and … after several months there, my pregnant mother and my father were relocated to Topaz, Utah where I was born.

“That’s why on my birthday, I always think of them…

“Thank you mom and dad, your hardships are not forgotten. ‘I love you and miss you!’”

At the end of his mother’s life, Kiyoshi was by her side. Still on her bed was a now-tattered quilt, a gift from a stranger 50 years before.

Kiyoshi’s sister, Satsuki, shares the following story of their mother and the quilt.

Shizuko, “quiet child,” was born in Seattle. The family lived in rural Lamona, on the outskirts of Skykomish in central Washington. When she was three, her mother died giving birth. Her father, unable to care for two young children by himself, took them to Japan to be raised by their grandmother Kisa in Nagano Prefecture. Shizuko clung to Isamu, her only sibling. And when he died of pneumonia a few years later, she carried for the rest of her life a burden of sorrow and loss beneath a sweet and feisty persona.

At age 16, Shizuko returned to the U.S. for schooling. She was placed in an elementary first grade class in Lamona due to her poor command of English. She told me, laughing, that the teacher had to find a special chair for her. Determined to succeed, Shizuko quickly moved through the grades in the one-room school and within two years left for Seattle where she found work as a live-in schoolgirl in a Caucasian doctor’s home. She managed to graduate from Garfield High School with her peers.

The “Silk Girl” from Nagano

My mother returned to Japan to care for her ailing grandmother. High taxes that had been levied to support Japan’s military campaigns impoverished small tenant farmers like her grandmother. Now bilingual and searching for ways to earn money, Shizuko learned of an opportunity to demonstrate silk reeling at the San Francisco Golden Gate Exposition of 1939. Out of 10,000 applicants, Shizuko was one of four young women selected by the Japanese government to represent the nation.

Shizuko quickly attracted notice as the beautiful “Silk Girl” from Nagano. She had many suitors in San Francisco, but when she was introduced to Itaru Ina, who was also a Kibei — born in the U.S., but partly raised in Japan — my mother told me that she was charmed by his confidence and presence. He was a poet, a Sunday school teacher at the Buddhist church, and an amateur kabuki performer. They got engaged and planned to marry a year later.

In letters written during the ensuing long-distance separation, she wrote my father from Japan on January 9, 1941, “After our wedding, we will never part from each other again. No matter how much you dislike me, I will hold on to you, and never, ever let go.”

Prison Camps

Shizuko and Itaru were married on March 30, 1941. Within the year, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and war was declared. Shizuko and Itaru were forcibly removed from their homes and dispatched with several thousand others from the San Francisco Bay Area to a prison assembly center at Tanforan.

Courtesy of National Archives. Original WRA caption: “Residents of Japanese ancestry appear for registration prior to evacuation. Evacuees will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.”

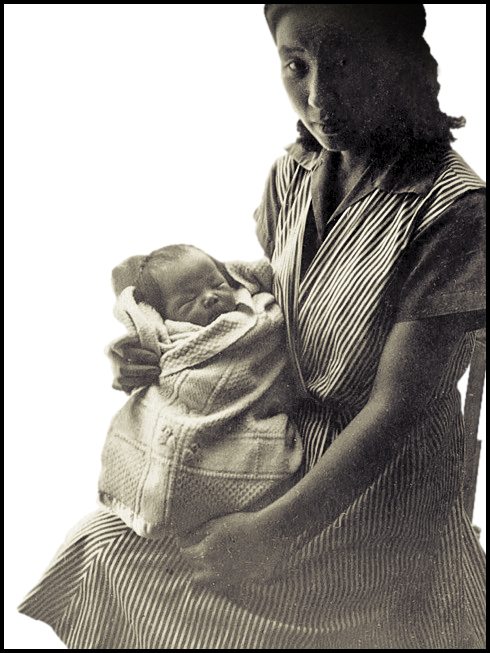

In April, 1942, Shizuko was pregnant with Kiyoshi. I learned this from her diaries: how tenderly she held my brother in her womb when the “evacuation” orders came that spring. Her sweet promise was to always protect him. Anxiety and sadness overwhelmed her as she rode the bus on a wet, dark day to the Tanforan detention center in San Bruno.

During her captivity there, south of San Francisco, women from the American Friends Service Committee would come to the fence and throw fruits and vegetables over the barrier to the prisoners.

One day, possibly noticing that my mother was pregnant, a woman heaved a quilted blanket over the barbed wire fence and called out to her, “I hope this helps.”

The handmade quilt from the Quaker woman, a stranger, traveled with Shizuko for years afterward, through several prison camps and during a period of separation from Itaru, when he was detained by the Justice Department for dissent. After the war, it was always a part of her bedding in San Francisco. But we didn’t think to ask about it. It was just a blanket underneath the chenille bedspread.

Someone Outside Cared

Half a century later, when my mother was ill and failing, she still kept that quilt on her bed. It was beautiful, strangely red, white and blue, but now faded and fraying. Not knowing its history, I suggested we discard it for a new one. She said, “no, don’t throw it away!” and explained how she had come to have it. She said, “I held on to this blanket in camp because it helped me to remember that someone on the outside cared.”

photo: Nancy Ukai

Ed. note: Dr. Ina uses the quilt in public talks at schools and other venues. It is now on display at Chico State University, Chico, CA, in the exhibition, “Imprisoned at Home” in the Valene L. Smith Museum of Anthropology until Aug. 2, 2018.

Satsuki Ina, Ph.D., was born in the Tule Lake concentration camp during WWII. She is Professor Emeritus at California State University, Sacramento, and currently has a psychotherapy private practice in Oakland, CA. She specializes in the treatment of community-based historical trauma. Dr. Ina has produced two documentary films on the subject of Japanese American incarceration, Children of the Camps and From a Silk Cocoon. Her upcoming book, The Poet and the Silk Girl: Love and Protest in an American Concentration Camp, will be published by Heyday Press in 2019.

Friends

The American Friends Service Committee provided rare moral and material support to imprisoned American Japanese during the war and after it ended.

Concentration camps to campuses

Quakers led the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council which moved college-age students out of the camps and onto college campuses. The Council helped liberate nearly 4,000 American young people from confinement to more than 600 colleges and universities. The Council arranged for logistical support, assisted with applications, student finances and did liaison work with colleges and towns.

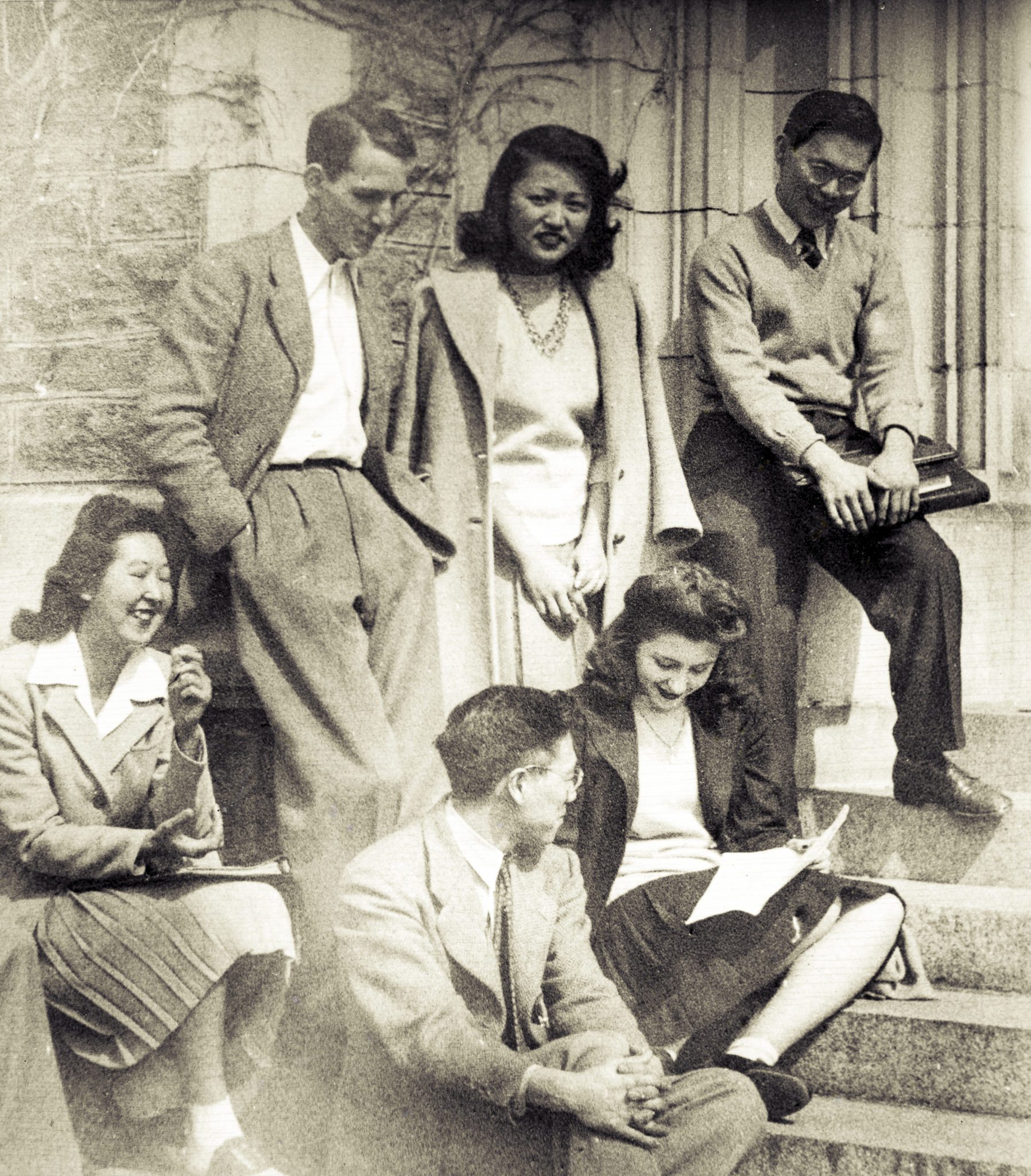

Photo shows students who were released to Swarthmore College, PA, in 1943. Courtesy of AFSC Archives.

'To atone for the violence'

Swarthmore president John Nason, chair of the Council, later said that the endeavor was “the single most satisfying piece of work I’ve done in my career.” Quaker activist and Council field director on the West Coast, Thomas Bodine, personally visited all 10 permanent camps.

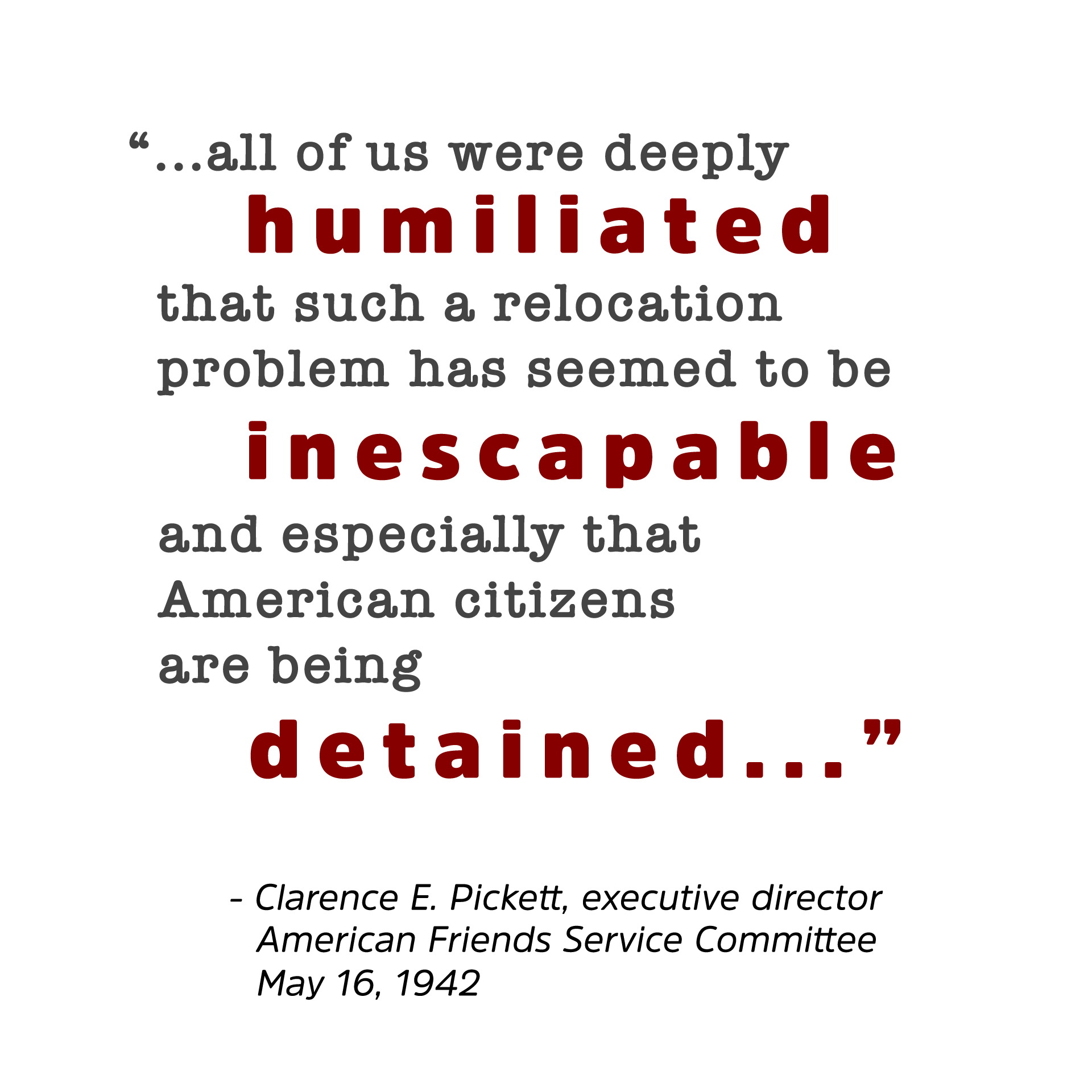

In a May 16, 1942, letter to WRA director Milton Eisenhower, AFSC executive director Clarence E. Pickett accepted the WRA proposal to coordinate a student relocation program. He wrote that only through such a program would it be possible “to atone for the violence that has been done to the constitutional rights of American citizens.” Correspondence courtesy of AFSC Archives.

Remembering a kindness

Ryozo Glenn Kumekawa, a high school student at Topaz, Utah, was accepted at Bates College, in Lewiston, Maine, in 1945, through the auspices of the Council. During the four “incredible” years of the Council’s existence, Ryozo’s sister, Nobu, was one of the first to be helped by the NJASRC and he was one of the last, he said.

Ryozo later volunteered for 20 years as board member and director of a scholarship fund established in 1980 in New England by his sister, Nobu Kumekawa Hibino and Lafayette Noda, and other Nisei in the Boston area. In 1980, the Nisei Student Relocation Commemorative Fund was founded, inspired by the work of the Council. The first award was to the AFSC.

The founding group wished to “repay a kindness” by helping a new generation of young people: the children of Vietnam war refugees who were at the time arriving in boats on U.S. shores.

Gratitude paid forward

The NSRCF is in its 38th year. It continues to help students of Southeast Asian descent pursue degrees at vocational schools and institutions of higher learning. Nobu’s daughter and the niece of Ryozo, Jean Hibino, and her daughter, Laura Misumi, are the second and third generations of the family to work on behalf of the scholarship fund. Former awardees are now helping to steward the program. Photo shows 2013 awards ceremony in Houston, TX. Photo courtesy of Jean Hibino.

Quilts of remembrance

Shizuko’s quilt, delivered to her by a compassionate stranger, accumulated a history of its own once it fell into her arms. The quilts below are different: contemporary pieces made collectively by women survivors who were moved to express personal stories of loss, resilience and community.

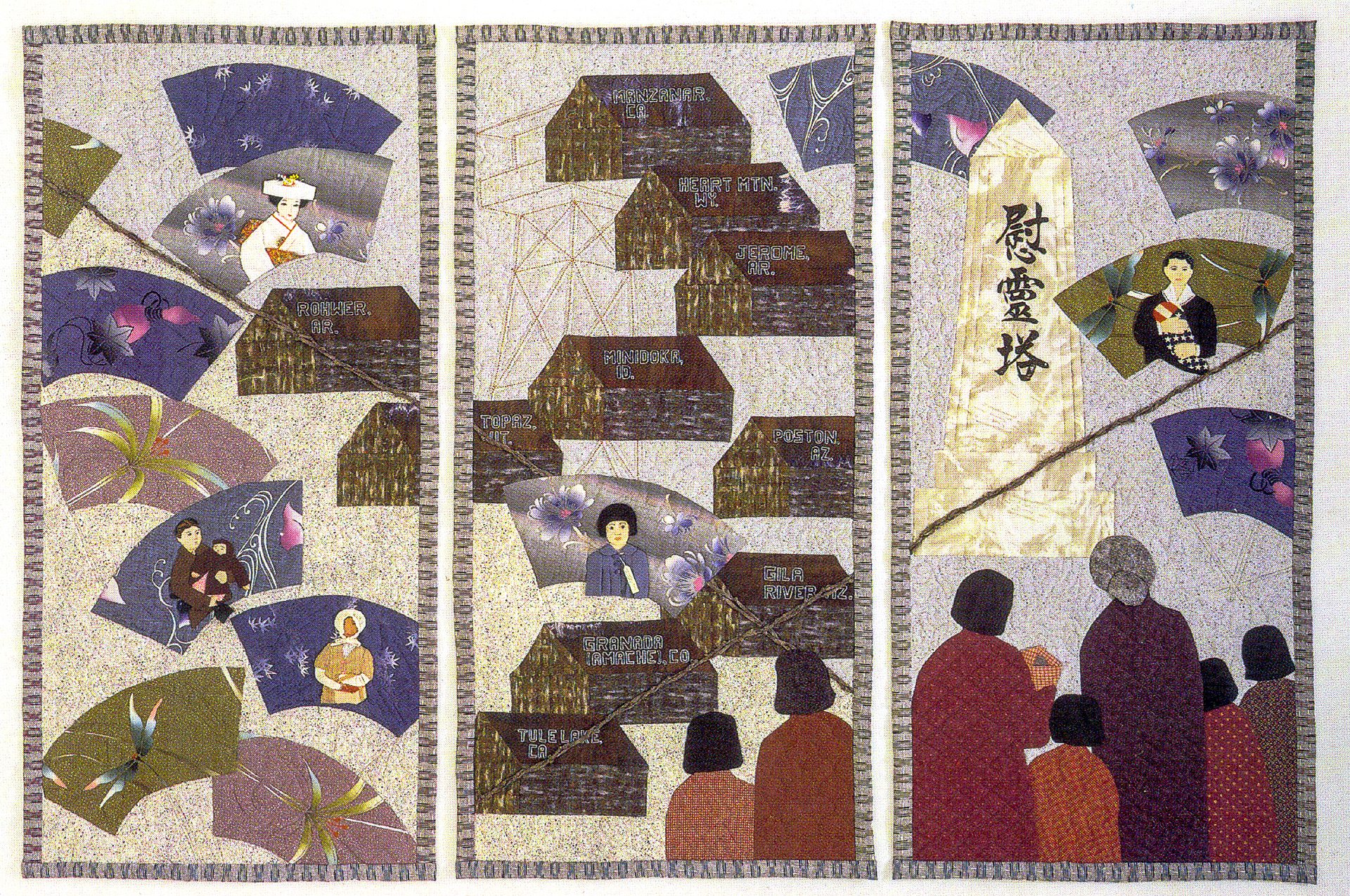

The “Threads of Remembrance” quilt honors three generations of American Japanese women. It depicts a picture bride, an immigrant Issei farmwife, a Gold Star mother, barracks, a sentry tower and barbed wire. One quilter incorporated her daughter’s hair into the farmwife’s bonnet. Another stitched her mother’s concentration camp family ID number on the registration tag of an illegally detained child.

Many women, including those who had been wrongfully confined, took a symbolic stitch in the quilt. Others cried as they touched the quilt and urged that the incarceration not be forgotten. Issei women looked for “their” camp, the names stitched onto barrack rooftops.

The quilt was created in conjunction with the exhibition, Strength and Diversity: Japanese American Women, 1885-1990. The exhibition opened in 1990 at the Oakland Museum of California and traveled to Hawaii, the Midwest, the East Coast and Canada.

Daisy Uyeda Satoda suggested the creation of the quilt. Jan Inouye designed the three panels, each 33″ x 69.” The quilters were Bess Kawachi Chin, Margene Fudenna, Dolores Hamaji, Ruth Hayashi, Jan Inouye, Naoko Yoshimura Ito, Julie Kataoka, Karen Matsumoto, Phyllis Mizuhara, Hazel Nakabayashi, Iku Noma, Alys Sakaji, Kay Sakanashi, Setsu Shimizu, Tami Tanabe, and Yuri Uchiyama. Photo courtesy of National Japanese American Historical Society.

'Letting Go'

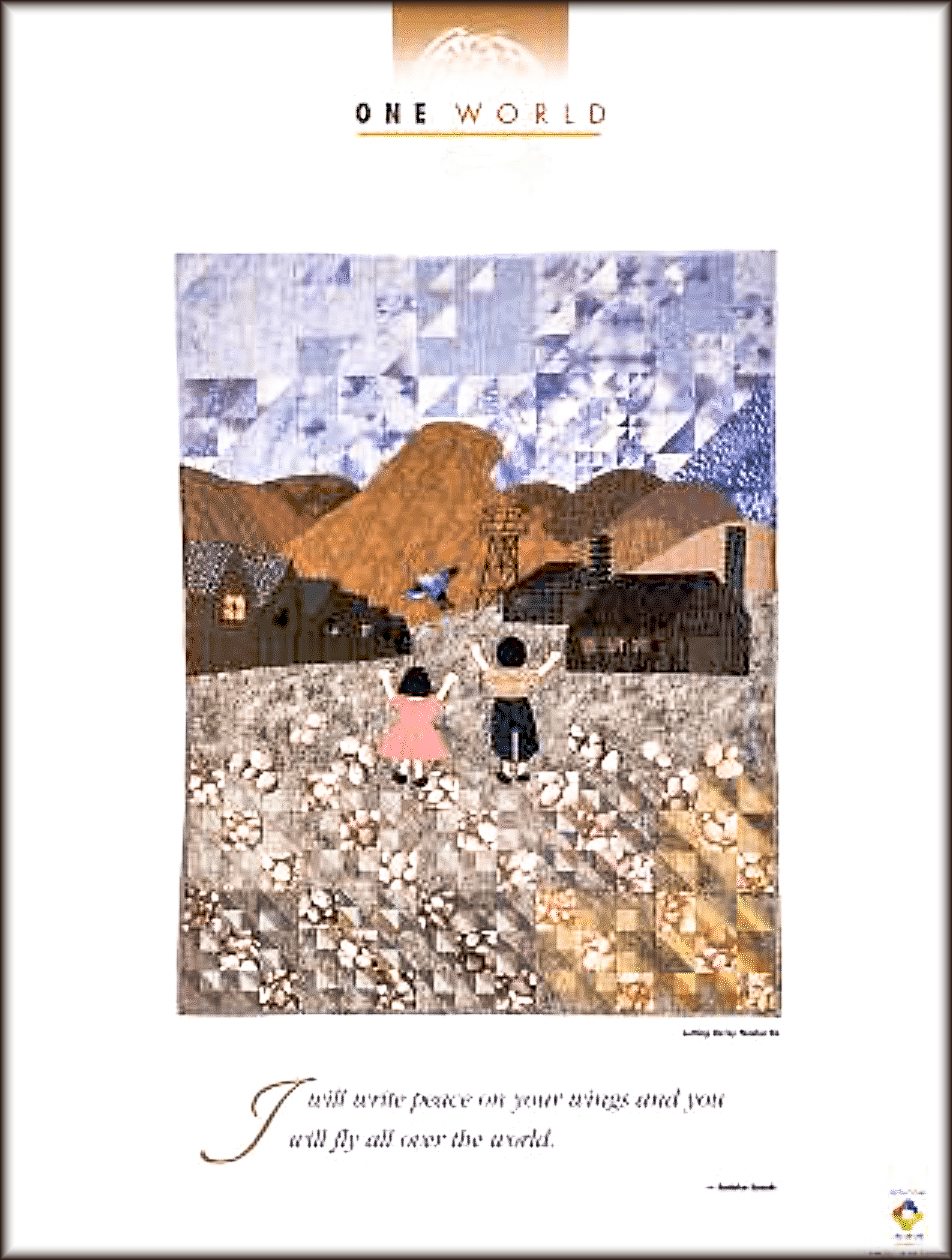

As a teenager, Naoko Yoshimura Ito of San Francisco was incarcerated at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. While there, she and her brother, Akira, rescued and released a baby bird, granting it the freedom they were denied.

The Southern Poverty Law Center selected Naoko’s poignant and aspirational quilt, “Letting Go,” for its “One World” poster.

'Piecing Memories - Recollections of Internment'

Bess Kawachi Chin’s education as a chemistry student at San Jose State College was terminated in 1942 when she was imprisoned at the Heart Mountain incarceration facility in Wyoming.

Fifty-seven years later, as a quilting instructor in Berkeley, CA, she led a group of Nikkei women, most of whom had also been removed to the camps, in the creation of “Piecing Memories.” It became a long-delayed expression of painful feelings that had been suppressed for decades.

“We would laugh and cry while we worked on it. It was a good healing process for all because each one had a story to tell.” – Bess Kawachi Chin

'Chicago is Home'

Seventeen Nikkei women in Chicago created a quilt in 2001 in the form of a kimono, inspired by the “Strength and Diversity” exhibition. Flag stripes, family crests in place of stars and images of guard towers and the names of the wartime camps symbolize citizenship as well as the government betrayal that led to the quilters’ settlement in the Midwest. The sleeves juxtapose natural vines and manmade barbed wire. This is the kimono’s exterior, its public face.

The interior of the kimono quilt records personal experiences, with photo images sewn into the lining and the character for “dream.”

Alice Murata was coordinator. The quilters were Pat Amino, Yaho Fujii, Ritsuko Inouye, Tomi Inouye, David Johnson, Ruth Kosaka, Elyse Koren-Camarra, Kiyoe Kunisada, Itsuko Mizuno, Akemi Nakano-Cohn, Nancy Ota, Setsue Tando, Asako Watanabe, Atsuno Becky Yamaguchi, Miye Yada, and Margaret Yoshimura. Courtesy Chicago Japanese American Historical Society. Photo courtesy of Sarah Nishiura.

Stitching community

A community quilting circle in Chicago brought together descendants of Japanese Americans who “resettled” in Chicago at the end of the war and African Americans whose family members moved to the city as part of the Great Migration.

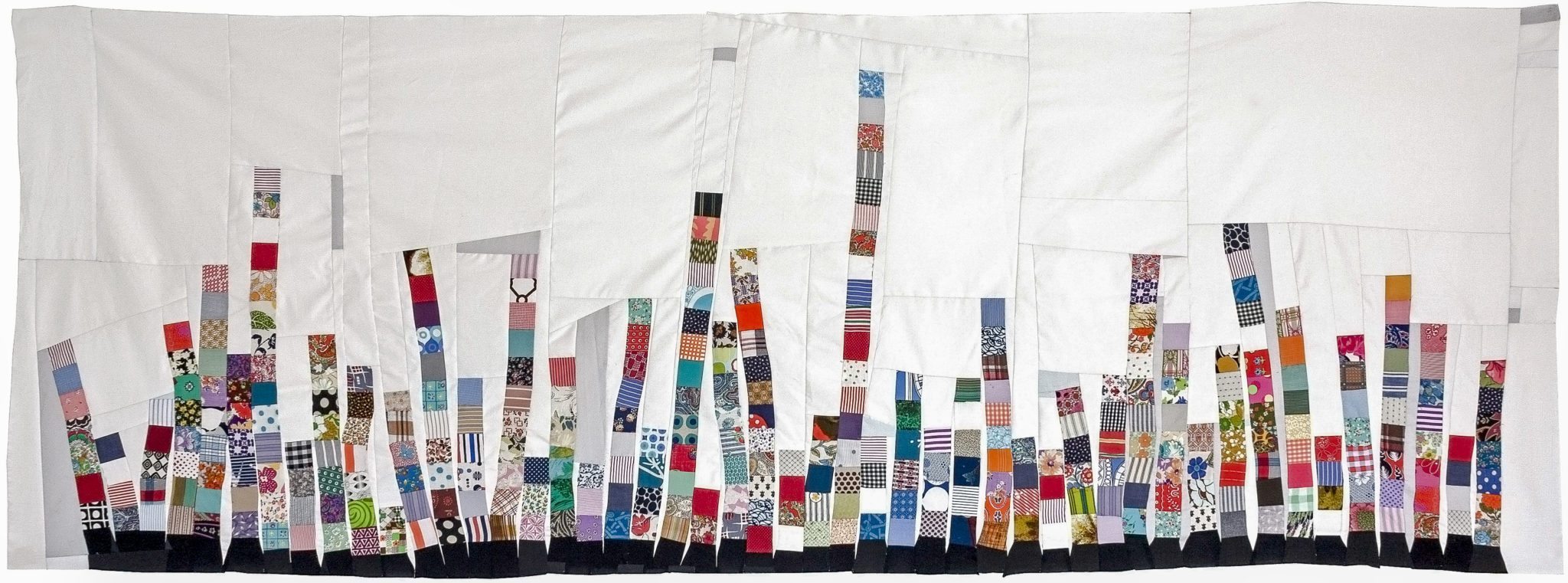

At the Midwest Buddhist Temple in May, 2017, quilters shared stories about their work and all participants sewed small cloth squares into long strips using a communal needle and thread. Organizer Sarah Nishiura took the strips and made a top (34″ x 92″) which will be finished into a quilt honoring the legacy, resilience and vibrancy of the two cultural communities.

The “Postage Stamp” quilt top “is meant to look less like the work of individuals, and more like an expression of unified community spirit,” she said. The “Chicago is Home” quilt, a textile ancestor, was on display.

“Threading the Narrative of (RE)Location” was organized by Project Prospera, which was founded by Kulsum Ameji. It also featured quilters Dorothy Burge, Reneau Diallo, Sarah Nishiura, Dorothy Straughter and Nik-ki Whitingham. Sarah’s great-grandfather Shinzaburo Nishiura, and his brother, Gentaro, were famed woodworkers at Heart Mountain.

The quilters

Credits

narrative: Satsuki Ina

video: Emiko Omori

image galleries: Nancy Ukai and David Izu

art direction: David Izu

cover images: David Izu, Dorothea Lange, Nancy Ukai

special thanks to:

Satsuki Ina, Kiyoshi Ina, William D. Nitzky, Naoko Ito, Patricia Ito, Jean Mishima, Alice Murata, Sarah Nishiura, Phyllis Mizuhara, Jean Hibino, Ken Kumekawa, Chiyo Moriuchi, Don Davis, American Friends Service Commitee, Rosalyn Tonai, Max Nihei and the National Japanese American Historical Society

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service,

Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant program