In the early months of 1942, six-year-old Amy Iwasaki would wake up each morning and go to the front door to see if her father’s packed bag was still there.

Her father had bought a leather satchel just big enough to hold belongings for a short trip. It loomed large in Amy’s life.

Genichiro had packed the bag and placed it by the door of their home in East Hollywood in case the FBI came to take him away. He was not guilty of anything other than being an immigrant from Japan, but in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, he was a potential spy in the eyes of the U.S. government.

“I woke up each morning afraid that he was gone,” Amy told a government commission some 40 years later.

The trauma of not knowing if her father would be taken away while she was asleep became a permanent childhood memory.

In the end, he was not arrested, but her uncle, who lived across the street, was hauled off to the Tuna Canyon detention facility for enemy aliens. When his family was moved without him to the Pomona fairgrounds, his five-year-old daughter, Jane, threw up on the bus.

From Pomona, the Iwasakis and Jane’s family were sent to the permanent prison camp called Heart Mountain in Wyoming. It held more than 10,000 people.

Amy saw snow for the first time in Wyoming, and she and her mother received a day pass to visit Yellowstone Park, so Amy used to recall her childhood days under armed guard as “fun.”

But when she underwent psychoanalysis in her mid-thirties, as part of her training to become a social worker, she wept as she “got in touch with the painful feelings of fear, rejection and shame.” She realized that she was unable to say the word “Jap.”

Long-supressed memories, such as having to leave her beloved pet behind, a baby chick, began to surface.

Odd events in camp that had gone unexplained were now examined: memories of adults whispering about a domestic beating. A case of child abuse which resulted in the victim’s becoming schizophrenic. Their beautiful neighbor, 19, who was single, pregnant and shunned by everyone. “She didn’t have friends,” Amy says, “so she was home a lot and taught me how to knit.”

A white social worker visited the pregnant neighbor and befriended Amy. “It made me feel so good that the social worker liked me, talked to me. She was hakujin,1and I thought all Americans hated me and here she was being kind and nice and interested in me. We were wanting acceptance because we did feel really rejected.”

Years later, when asked what her career ambition was, Amy would answer, without knowing why, “adoption counselor.”

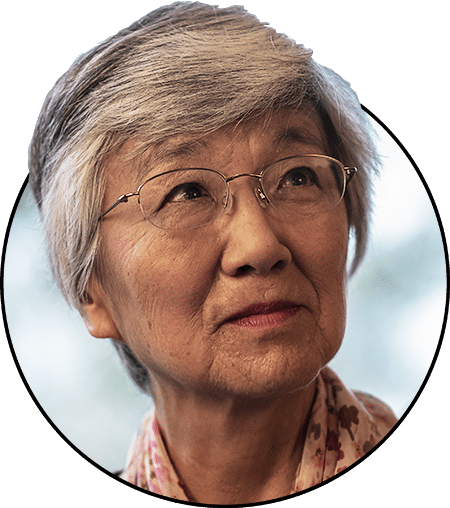

She completed a doctorate in social welfare at the University of California, Los Angeles, and began to teach and conduct research at Whittier College on the psychological impact of incarceration and “why so many Americans, Japanese and otherwise, were able to rationalize, justify and deny the injustice and destructiveness of the whole event.”3

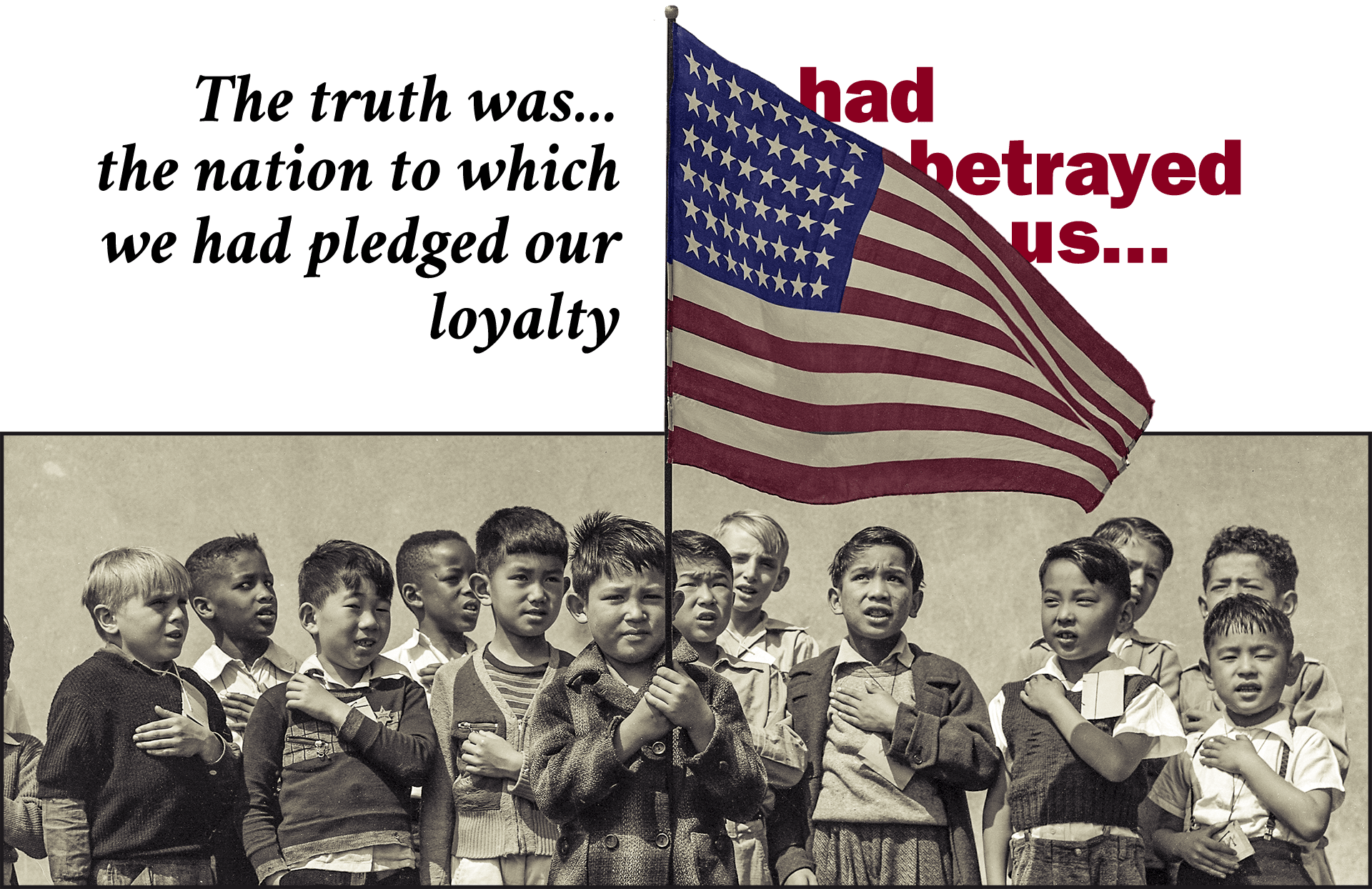

She concluded that survivors had buried their feelings of betrayal by the government. Like an abused child who wishes to be loved by an abusive parent, American Japanese worked hard to reestablish themselves and gain acceptance, but in denying the racism and not confronting the rejection, humiliation and shame of having a Japanese face, the trauma was buried. She realized, “I was ashamed of being Japanese and it made me feel guilty, because I loved my parents.”

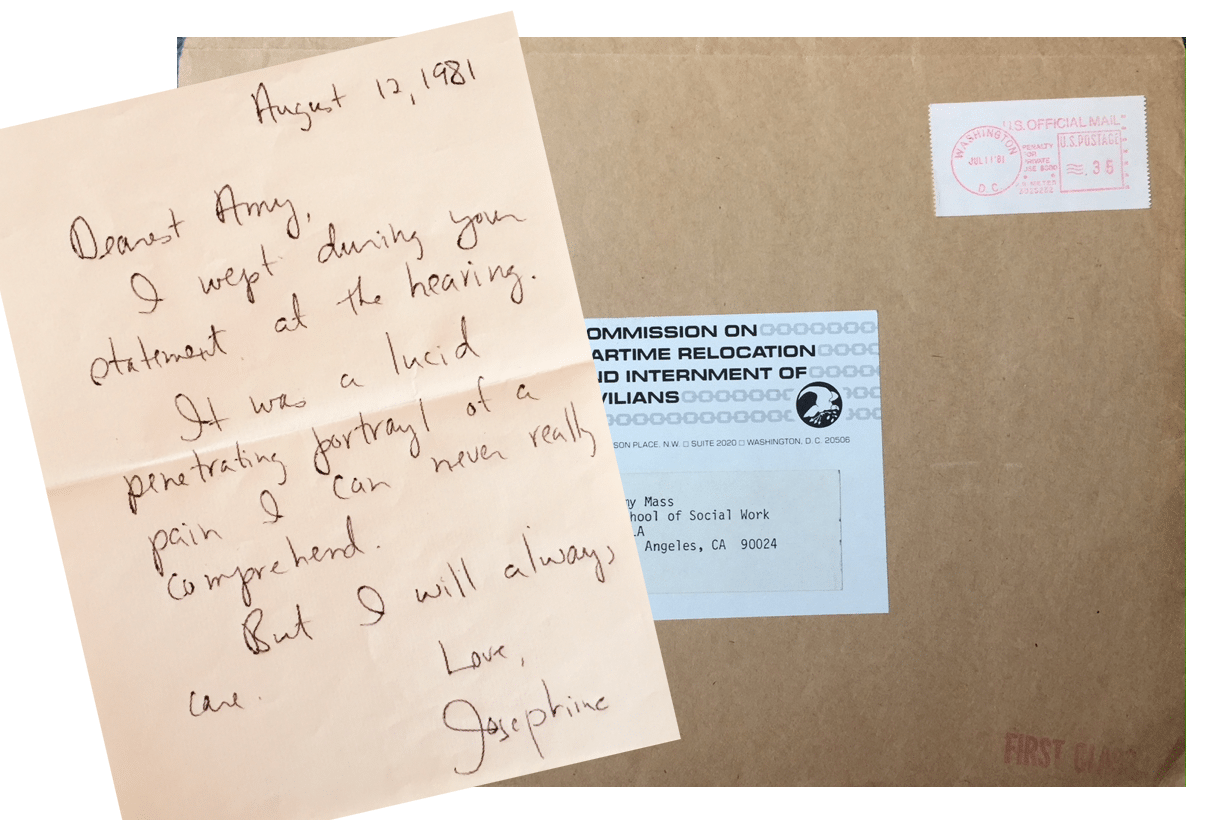

Her research became the basis for powerful testimony that she gave at government hearings in 1981 as a member of a mental health panel in Los Angeles. She was among more than 750 American Japanese who spoke in 10 cities before a federal commission that was charged with producing a report on the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The Commission on Wartime Internment and Relocation of Civilians (CWRIC) concluded that the mass exile of 120,000 Japanese Americans was not a “military necessity” and that it resulted from “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”5

In 1988, after years of struggle, which included grassroots organizing, a class action lawsuit, and a legislative lobbying campaign, the Civil Liberties Act was signed into law by President Reagan. Modeled after the recommendations of the commission, the bill provided for a formal presidential apology and individual monetary payments to camp survivors.

By the time payments were distributed, however, Amy’s parents, like many in the immigrant generation, were no longer alive to receive them.

Amy had worried that her public testimony might upset the rest of the family, but they supported her.

Twenty years earlier, she and Howard Mass, who was white, had married, an act that resulted in families on both sides disowning them. The first minister they talked to said he would marry them but that they should not have children. Amy took their children, Kevin and Julia, to redress meetings as part of their political education.

Eventually, Amy and Howard reconciled with their families. Julia became a civil rights attorney and worked for the American Civil Liberties Union for 15 years. Amy received a Fulbright Teaching Award and continued her career in social work for five decades.

Her father’s leather bag, now scuffed and worn, has softened with time. The life that the object has lived is reflected in the scars and blemishes it has picked up along the way. It is stored in a closet next to boxes of Christmas ornaments and now serves as a container for family documents and photographs.

But touching it now also recalls a time of racial fear and hatred that Amy worries may be returning. She holds the bag on her lap, grasping the handles, a tangible connection to a time when families were fractured, rights were removed and sleep was unsettled.

Family photos

Genichiro Iwasaki was born in 1892 in Numazu, Shizuoka. He came to the U.S. at age 16 “for the adventure” and worked in Seattle’s Pike Place market. He returned to Shizuoka to marry Misa Kurihara, of Mishima, and they came back to Seattle. The couple had three children and moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s, where Amy was born in 1935.

Left: Newlyweds Misa and Genichiro, 1919, Seattle. Courtesy Amy Iwasaki Mass.

Genichiro’s younger brother, Masayoshi, arrived in Seattle from Japan in 1927. Eventually the extended family moved to Los Angeles, where Amy was born. From left: Naomi (Nails), Misa, Masayoshi, Shogo, Genichiro, Fumie. Seattle, c. 1927.

In Los Angeles, the two brothers and a cousin, Yoshio, formed Three Crown Produce. At the time that the war broke out, they were leasing space in more than 10 Thrifty Marts where they sold fresh produce.

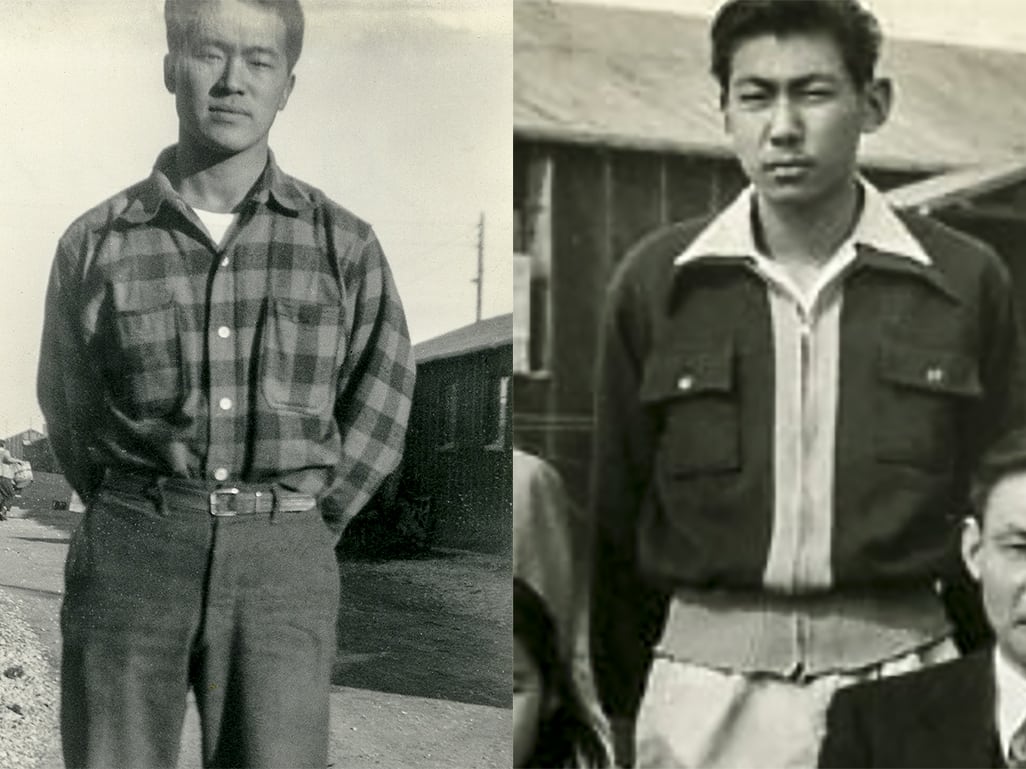

While the family was in Heart Mountain, Amy’s two older brothers were drafted and served in the Military Intelligence Service.

Nails served in the Philippines and interviewed POWs from Japan. He then went to Tokyo to join his brother, Shogo, who served as a translator for General MacArthur during the Tokyo War Crimes Trials. From left: Nails, Amy, Genichiro, Misa and Shogo at barrack 1-9-B, Heart Mountain, c. 1944.

The Iwasakis lived at 639 North Westmoreland Avenue, in a racially-mixed, working-class neighborhood in East Hollywood. “It was a good street,” Amy says. Among their neighbors were Frank Emi and Tak Hoshizaki, who in 1943 were among 63 young men at Heart Mountain who were tried for refusing induction into the U.S. Army as long as they and their families were imprisoned. They went to federal prison for their resistance.

Yorozu and Shigee Homma lived a block away on North Virgil Ave. (Object 2: The Homma Chair). Photo from left: Frank Emi and Tak Hoshizaki, Heart Mountain. Courtesy Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and Tak Hoshizaki.

Amy’s mother, Misa, became friends with Kane Mineta at Heart Mountain. The women, from Los Angeles and San Jose, were both born in Shizuoka.

One of the Mineta’s sons, Norman, was 11. He went on to become mayor of San Jose, a U.S. congressman and Cabinet member during the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, and was a leader in helping move the redress bill to passage. Photo: Misa, Kane and Kunisaku Mineta, visiting the Iwasakis, 1948.

Amy’s sister, Fumie, was an undergraduate at the University of California, Los Angeles, when the war broke out. She was forced to drop out due to the five-mile travel restriction for Japanese Americans. Fumie finished her education at Park College, Missouri, and became a special education teacher. From left: Fumie, Misa and Amy and Howard’s son, Kevin, 1971.

Credits

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: luggage by David Izu, 2017, other photos courtesy of Amy Iwasaki Mass. Coloring by David Izu)

Special thanks to:

Amy Iwasaki Mass, Howard Mass, Tak Hoshizaki, Susan Hayase, Dakota Russell, Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, Abraham Ferrer, Visual Communications, Densho

Supported in part by the National Park Service