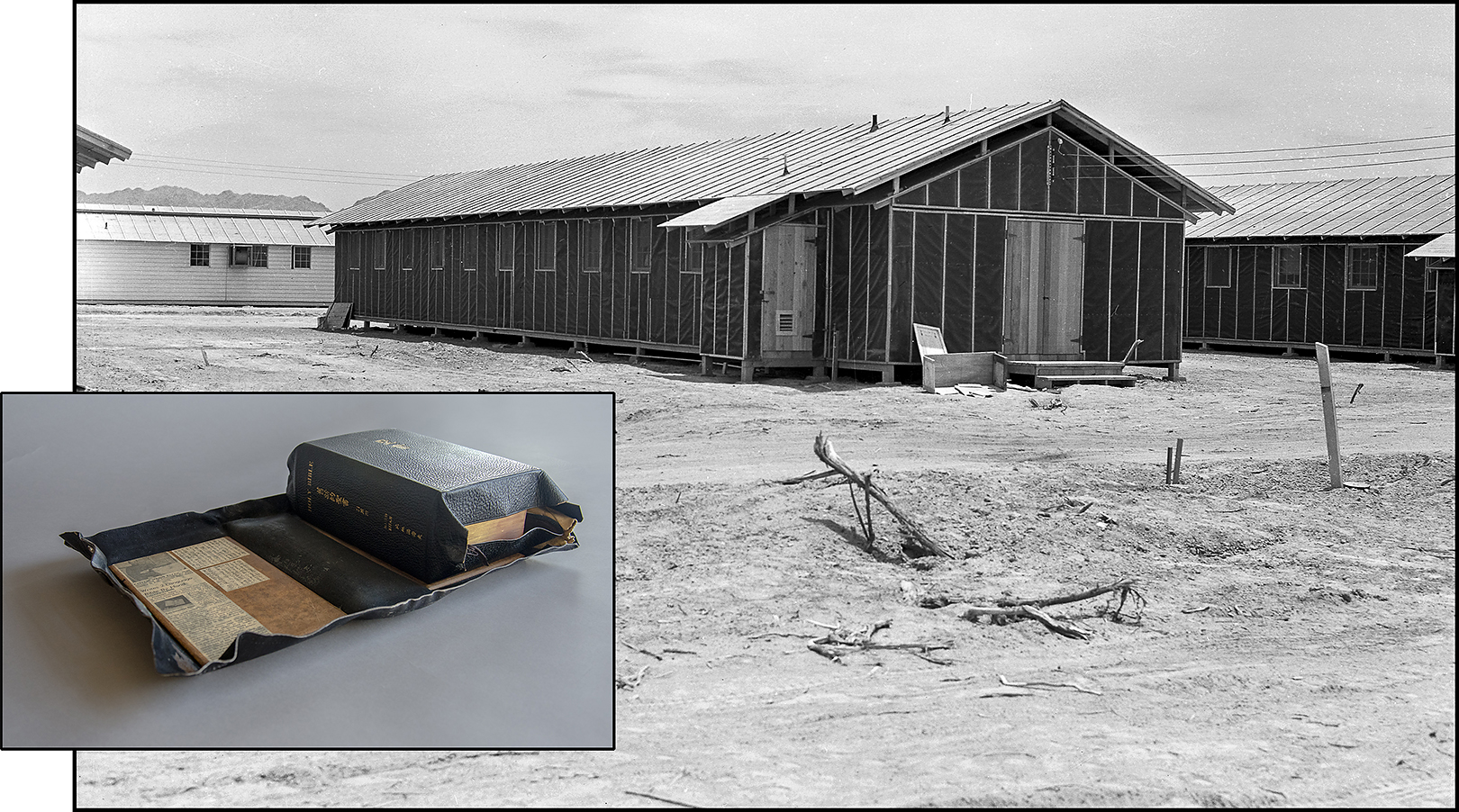

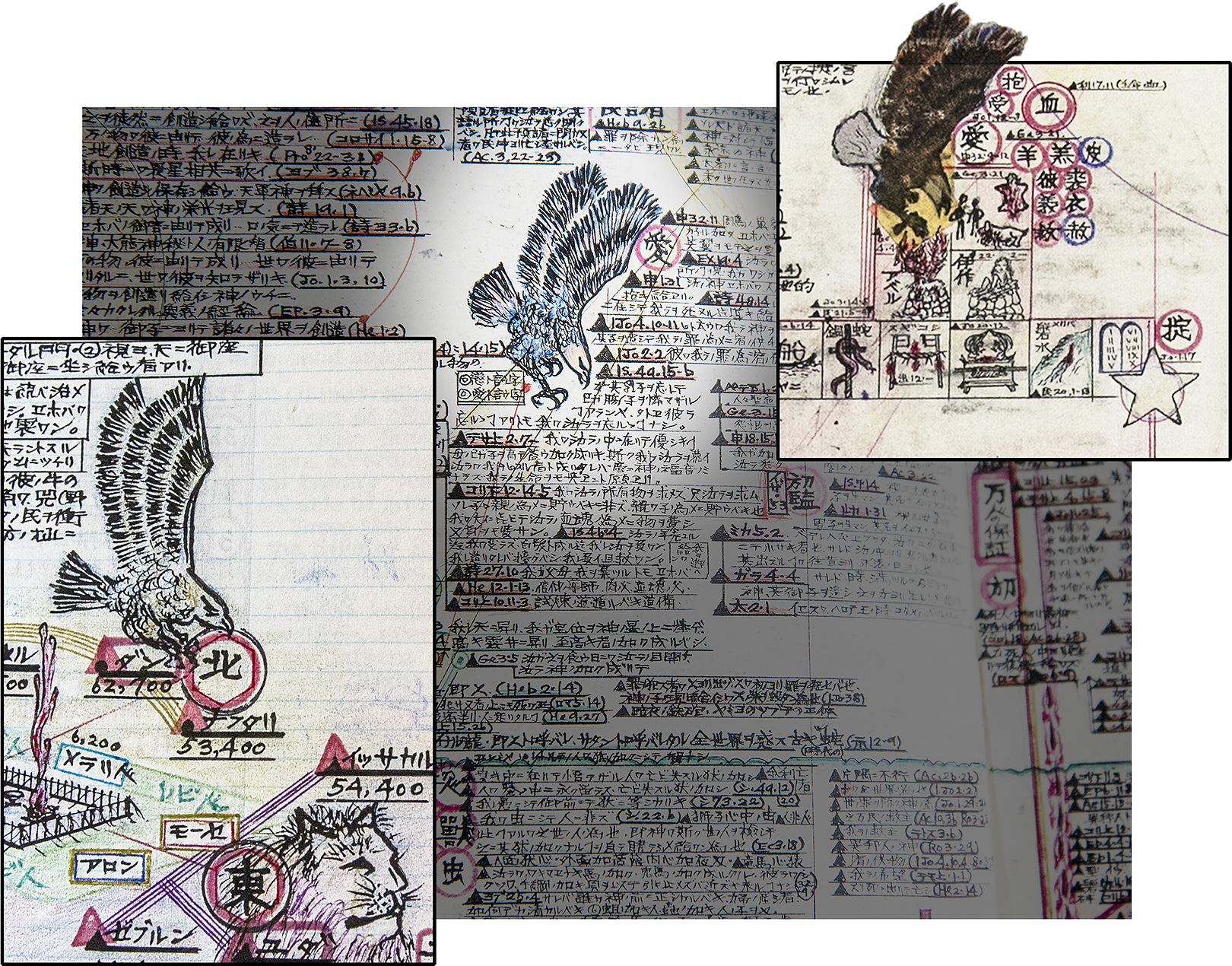

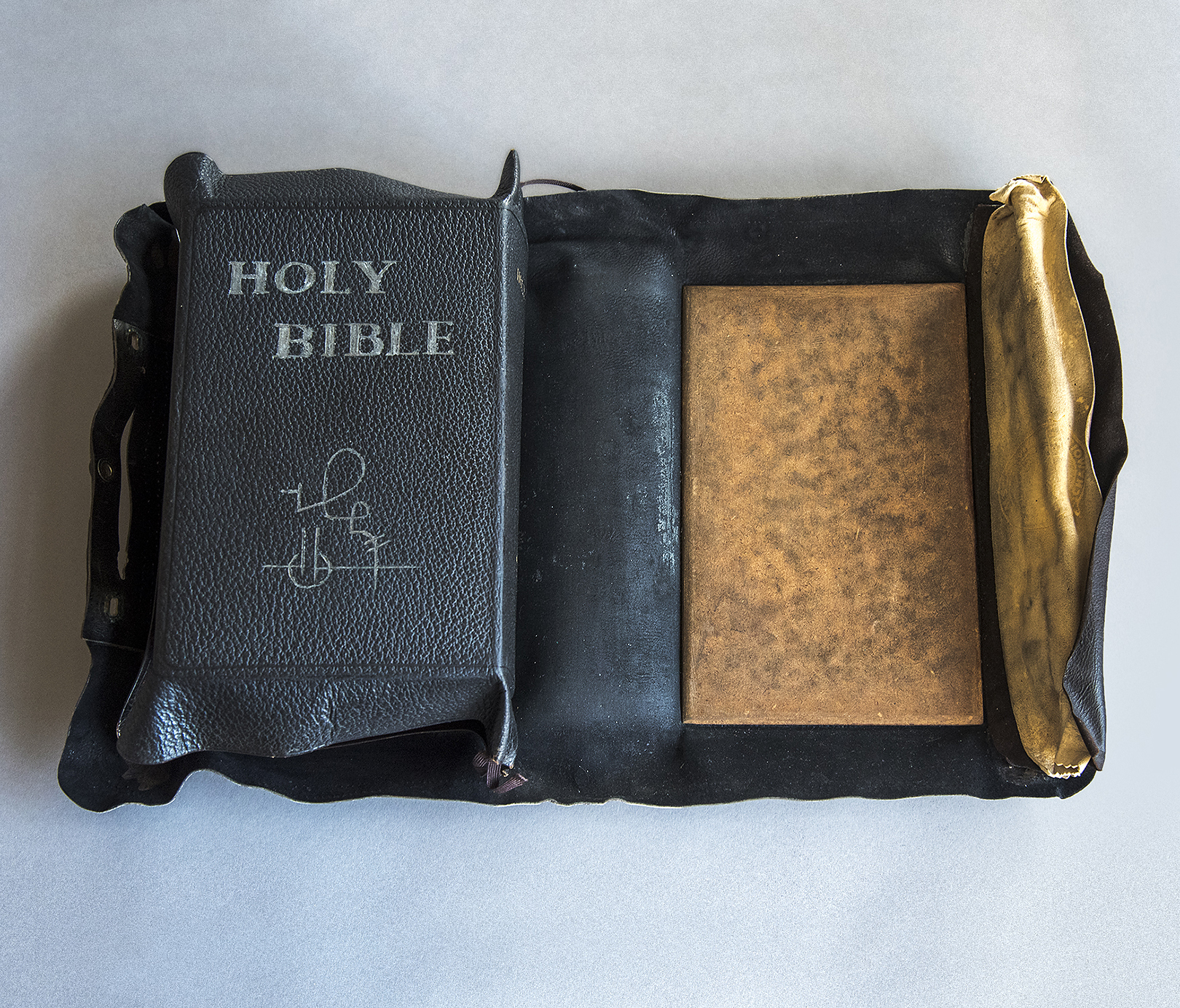

When Captain Masuo Kitaji entered two different prison camps for Japanese Americans in 1942 — Santa Anita, California, and Poston, Arizona — he carried with him his life’s work: a bilingual Bible that he had been annotating, transcribing and illustrating for five years.

His goal was to use the Bible someday in his sermons for the Salvation Army and to help other Japanese immigrant ministers.

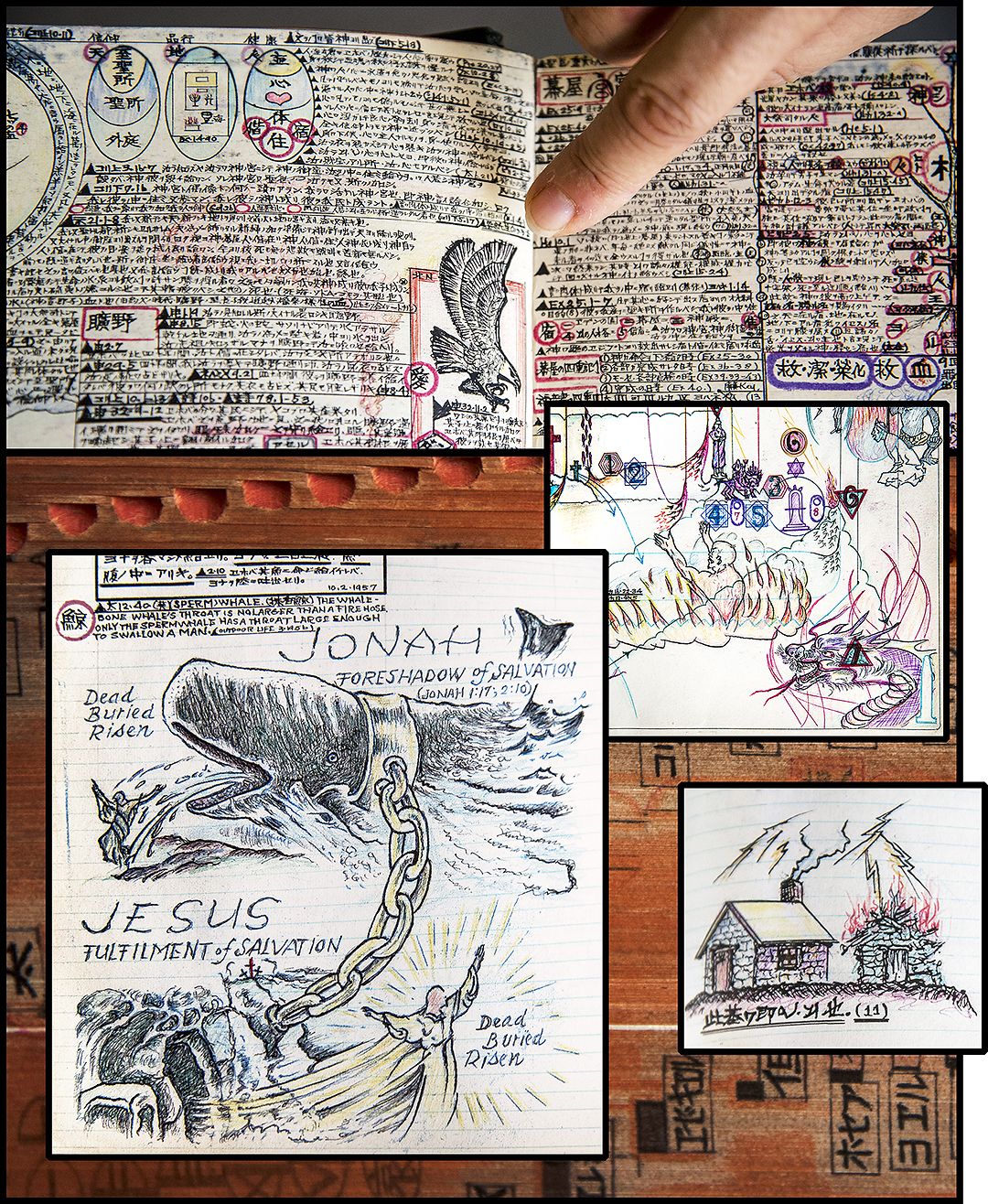

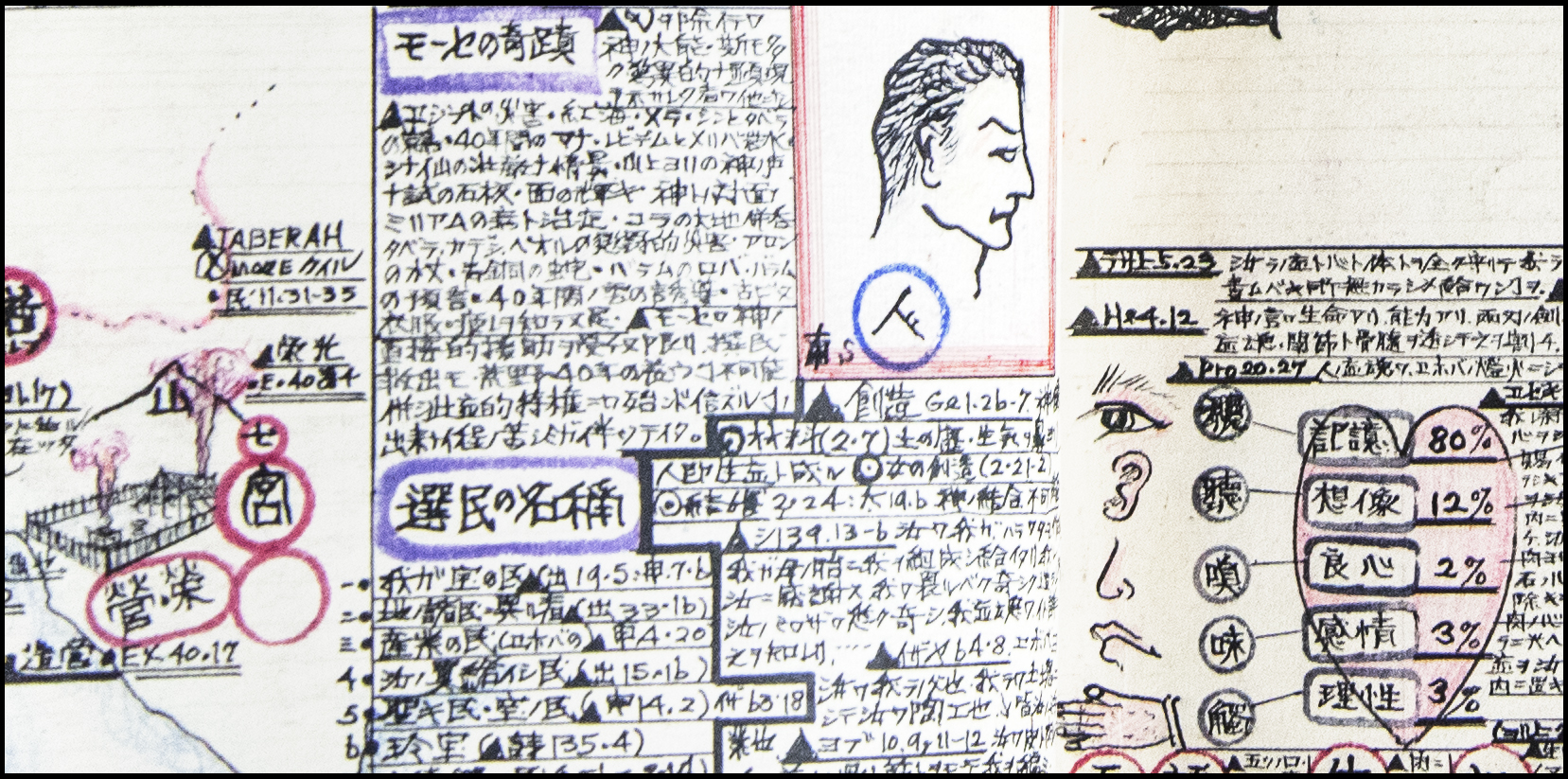

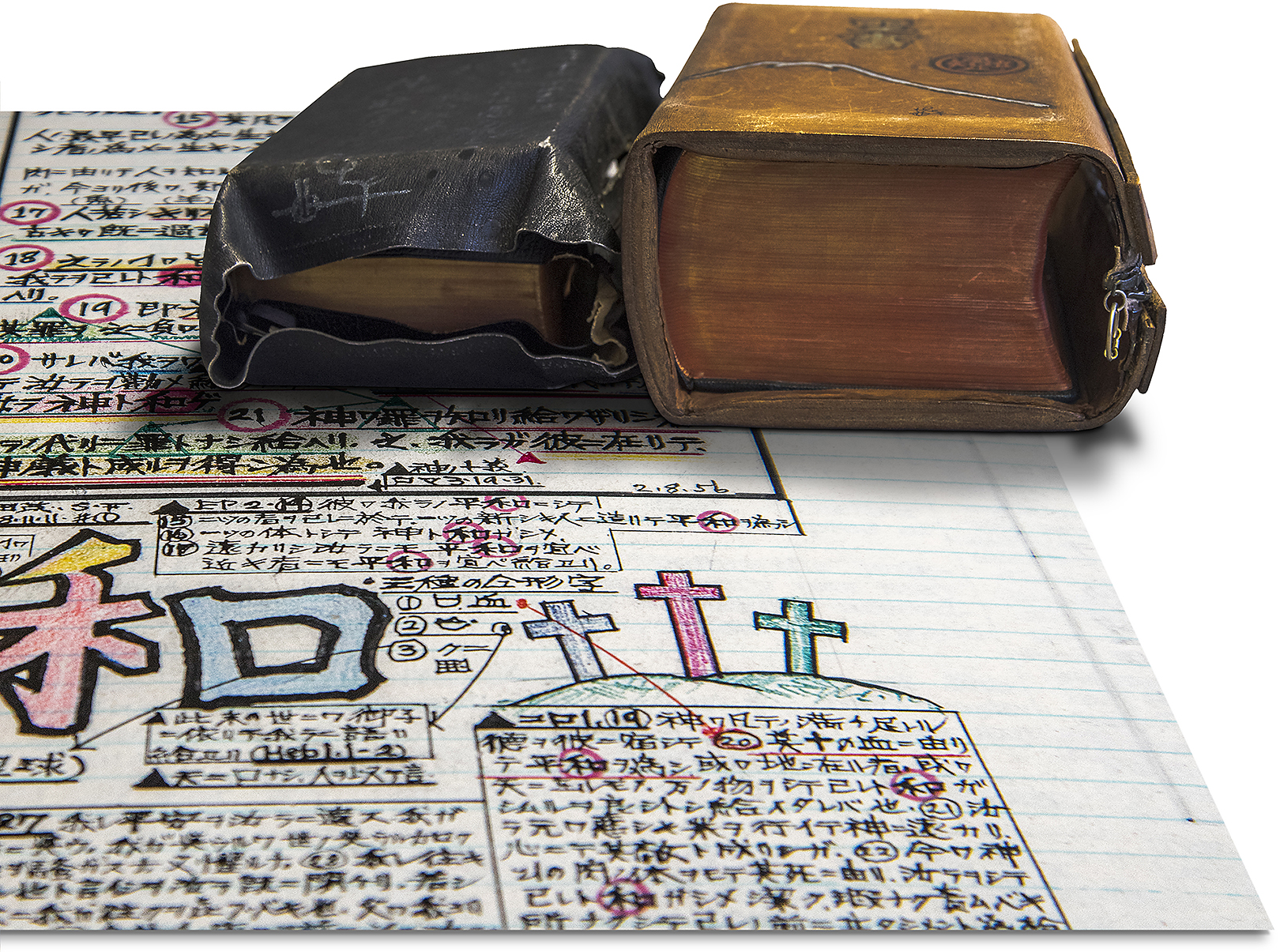

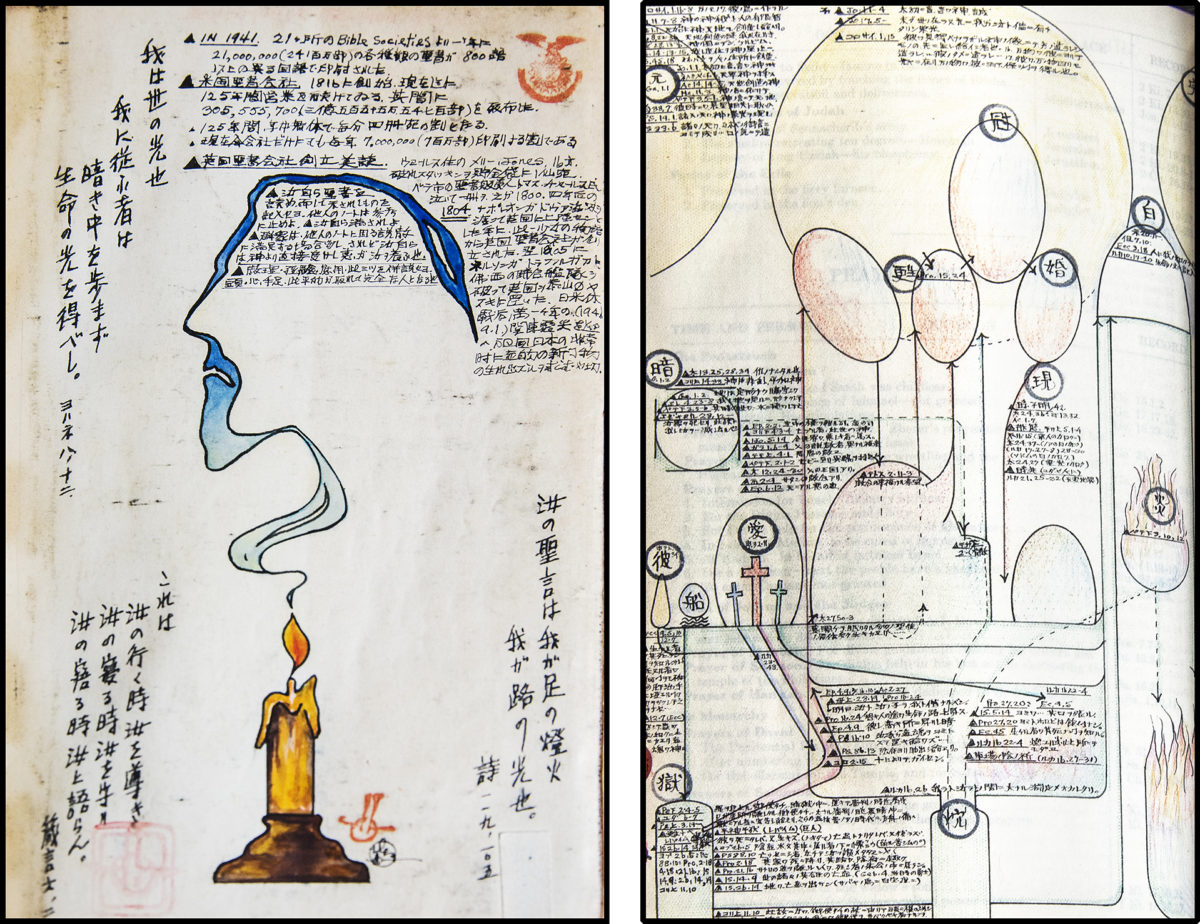

He began his day at 5 a.m. and worked until noon on his monument of faith. Kitaji wrote line after line of microscopic text with the aid of a magnifying lens, said Pauline Kitaji Wada, a niece who watched him at work.

“I remember watching Uncle as he sat with his magnifying glass over his glasses as he wrote in the Bible,” she recalled.

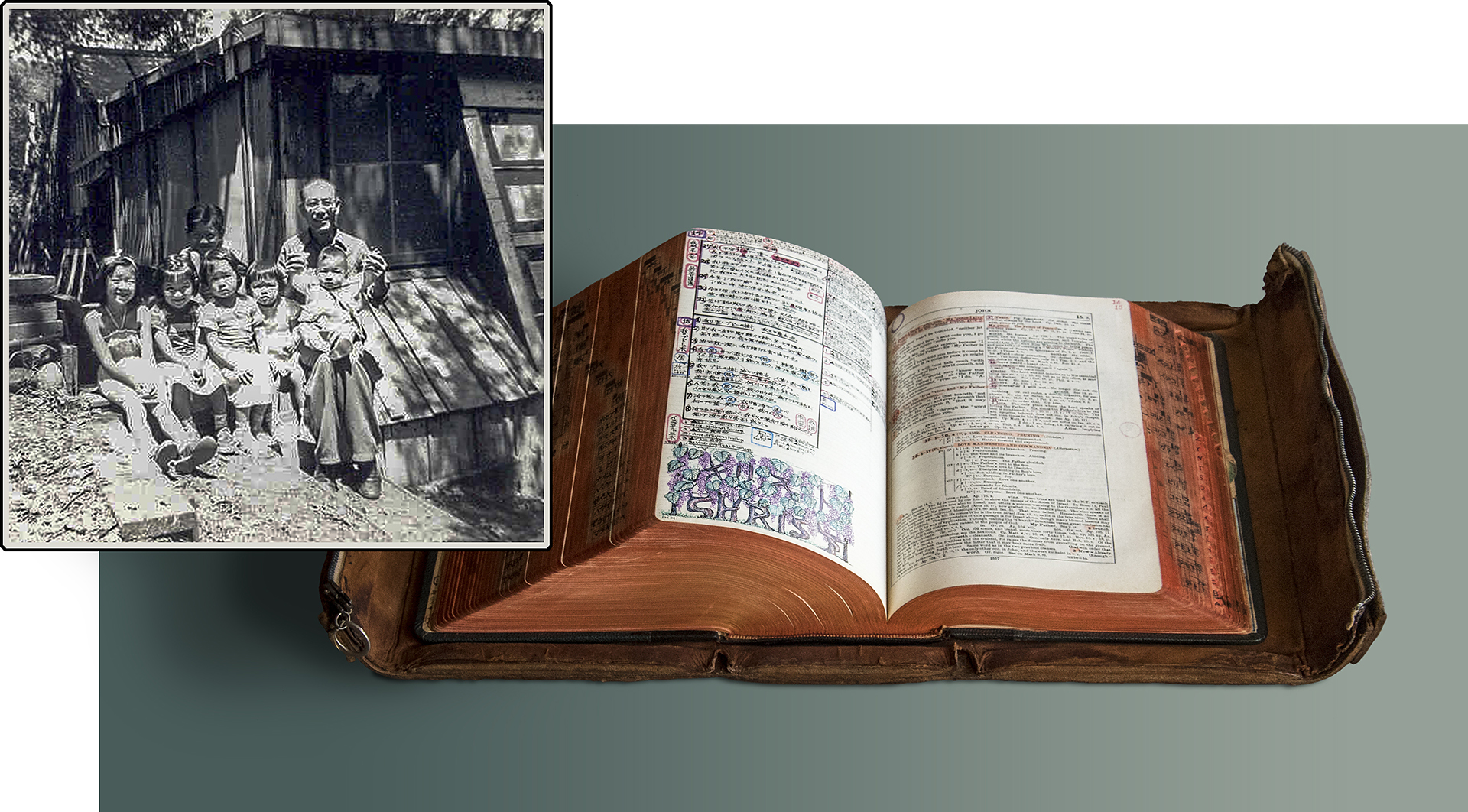

Kitaji completed the Bible at Poston II, one of three units at the camp. He commemorated the occasion with a photograph of himself and his masterpiece, dated April 18, 1944.

After the war, Kitaji returned to northern California, from which he had been captured and expelled, to manage the Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs, a 400-acre health spa for Japanese Americans before the war, and which became a postwar refuge for sixty displaced families who had been released from the camps but had no homes to return to.

In 1953, at the hot springs, Kitaji embarked on creating a second, companion Bible. Although he never finished it, the second volume contained even more elaborate illustrations, including a powerful depiction of Jonah’s whale.

He encased both Bibles in custom leather wrappers embossed in gilt, elevating their dignity and enhancing their physical protection.

Unlike other artifacts produced in the WWII camps, such as a chair made of practical necessity, or a wooden plaque whittled to fill long days, Kitaji’s project of religious passion took place over a span of approximately 20 years, before, during and after his incarceration.

Yet when they appeared, shockingly, for private sale in New York, in 2017, they were marketed as a “Pair of Illustrated Japanese-American Bibles Created by Masuo Kitaji in the Poston Relocation Center.” The price was $85,000, set by Swann Auction Galleries.

Kitaji’s descendants were stunned. They had assumed the Bibles were safe within the family. A private sale at a price they could not afford would mean permanent loss of an irreplaceable part of their childhood memories and family heritage.

“The price of $85,000 feels like a ransom,” the family wrote to Swann after learning of the sale. “It is an insult to our Uncle Captain who, as a Salvation Army officer, said many times that he wanted to help other Japanese-language preachers by publishing his Bibles — but not for profit.”1

Conversion to Christianity

It’s not surprising that a commercial enterprise would highlight Kitaji’s concentration camp years as a selling point.

The genesis of the story actually began long before Kitaji’s imprisonment, with his conversion from Buddhism to Christianity.

Masuo Kitaji was born in 1897 in Shingu, Wakayama, the eldest of nine children. His father, Kikumatsu Kitaji, emigrated to the U.S. to find work the year after Masuo was born, leaving the child behind to attend the prefectural school and also a monastery to study traditional arts and to receive “training conducive to a religious life,” said Kitaji’s niece, Laura Kitaji Dominguez-Yon.

But when Kitaji arrived in the U.S. in 1915, he ended up working at Kitaji Sokai, the family’s dry goods store in Watsonville, California, after graduating from the local high school and studying art for six months at the University of California at Berkeley.

The store, Dominguez-Yon wryly notes, was “not so dry, they made bootleg liquor during Prohibition, had a bar and poker room, and Masuo Kitaji was the bartender, delivery boy, bill collector and trusted business partner.”Describing him in a 1920 family photo, in which he sports a beret and dark glasses, Dominguez-Yon said, “he was California’s first hippie.” In 1923, Kitaji is listed on a ship manifest as being a musician living in San Francisco.

In 1925, the death of his beloved younger sister, Evelyn, at age 18 due to tuberculosis, left him grief stricken. After a motorcycle accident that occurred while he was drunk, a Salvation Army follower found Kitaji at the crash site and nursed him back to health. Kitaji found his true religion. He converted to Christianity and studied to become a Salvation Army minister.

He graduated from officer training school in San Francisco and by 1933, at the age of 36, was delivering sermons to Japanese immigrant congregations in San Jose and Oakland when he realized that he needed a dual language Bible for his work. He acquired a 1929 version of the New Analytical Indexed Bible and began his long labor of faith.

Kitaji acquired the rank of “captain” in the Salvation Army in 1941 and was thereafter called “Uncle Captain” by his nieces and nephews.

Kanji characters

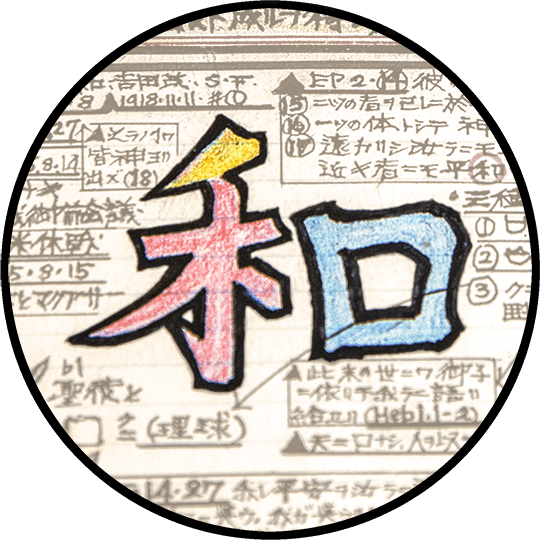

Kitaji’s conversion from Buddhism surely played a part in how he interpreted the Bible and also why the evangelist became dedicated to seeing the religious tradition propagated and properly explained to followers. His annotations and drawings show that when Kitaji found that he wanted to explain Biblical teaching in a Japanese context, for example, he used kanji characters to depict concepts and inserted them into his religious drawings.

“The Kitaji Bibles are American Bibles that arose out of Japanese American culture and spirituality,” said Fumitaka Matsuoka, Professor of Theology Emeritus at the Pacific School of Religion. “The Bibles are distinctly American,” he said, and respond to a question that early Japanese immigrants, almost all of whom were Buddhist, may have faced: “How can I be Christian without being Buddhist?”

Kitaji’s works also served as traditional family Bibles. He recorded the baptisms of nieces and nephews in their pages and used them for Sunday school lessons. “They were instrumental in teaching us Bible stories,” Pauline said. “He also taught us about nature and caring for others.”

Kitaji dedicated several pages to autobiographical information and important historical dates in his personal history, including the dates of his immigration, incarceration and the nuclear attack on Hiroshima.

Detained

Kitaji also recorded notes in the Bible about his worries about his fiance in Japan, Yuko Tsuruta, who also was a captain in the Salvation Army. She was en route to California to marry Kitaji when the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, forced her ship to turn around. The couple did not wed until May 1, 1952, at Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs.

Kitaji also had to decide in early 1942 how to respond to the Salvation Army’s instructions that he relocate to the East Coast to avoid the camps that were looming as a result of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066.

But Kitaji refused to abandon his flock, Dominguez-Yon said.

“He said, ‘Every ship has a captain, every sports team has a captain. I am captain of my people!'” The captain was sent to Santa Anita on May 29, 1942, and to Poston II on Aug. 26.

War Relocation Authority packing records show that Kitaji possessed in Poston several crates’ worth of hymnals and Bibles. In addition to transcribing the first Bible, he was preaching and teaching Sunday school, a part of the rich and varied religious life in the camps, including its material culture.

“The altars, prayer beads, rosaries, service books, crosses, scriptures, statuary, and other implements of faith that were used or created in camp, many of them handcrafted, testify to the persistence and ingenuity of Japanese American faith in even the most difficult of circumstances,” write scholars Duncan Ryuken Williams and Emily Anderson.3

“By drawing on sacred scriptures, ritual practices, and each other, Japanese Americans were able to find a degree of freedom even when their civil liberties were taken away.”4

The Kitaji holy book was in the company of other Bibles that survived censors, bore witness to family separations and bear the marks of imprisonment, despite the fact that Christianity was a privileged religion in the eyes of the U.S. government, Williams and Anderson note.

“Mitsuji Furuta’s worn copy of the New Testament & Psalms, one of the few items he managed to grab while being arrested in February, 1942 by the FBI, traveled with him to the Tuna Canyon Detention Station, the Santa Fe Internment Camp, and ultimately the Poston concentration camp where he was finally reunited with his family.” 5

Incarceration dispersed the Kitaji family after they arrived in Poston. Kitaji’s widowed mother and sister remained there, along with two sisters-in-law, while Masuo’s brothers were eventually released to Nebraska and Idaho, with a third brother entering the U.S. Army.

Social service, artist, carpenter

On a War Relocation Authority form at Poston, Kitaji listed “social service, artistic work, artist and carpenter” as occupational skills, all of which he used there.

In addition to his daily writing of the first Bible, the Captain proposed the construction of a facility to care for the ill and aged, which was not approved by authorities.

He also had a more prosaic request: a bicycle.

“Captain Kitaji’s work covers the areas of the three units of the Colorado River War Relocation Center, the distance between the units being approximately eight miles. Added to this is the fact that he must travel many more miles from barrack to barrack,” wrote clerk Hugo T. Kazato of the legal department.9 The bicycle request was granted.

Return to California

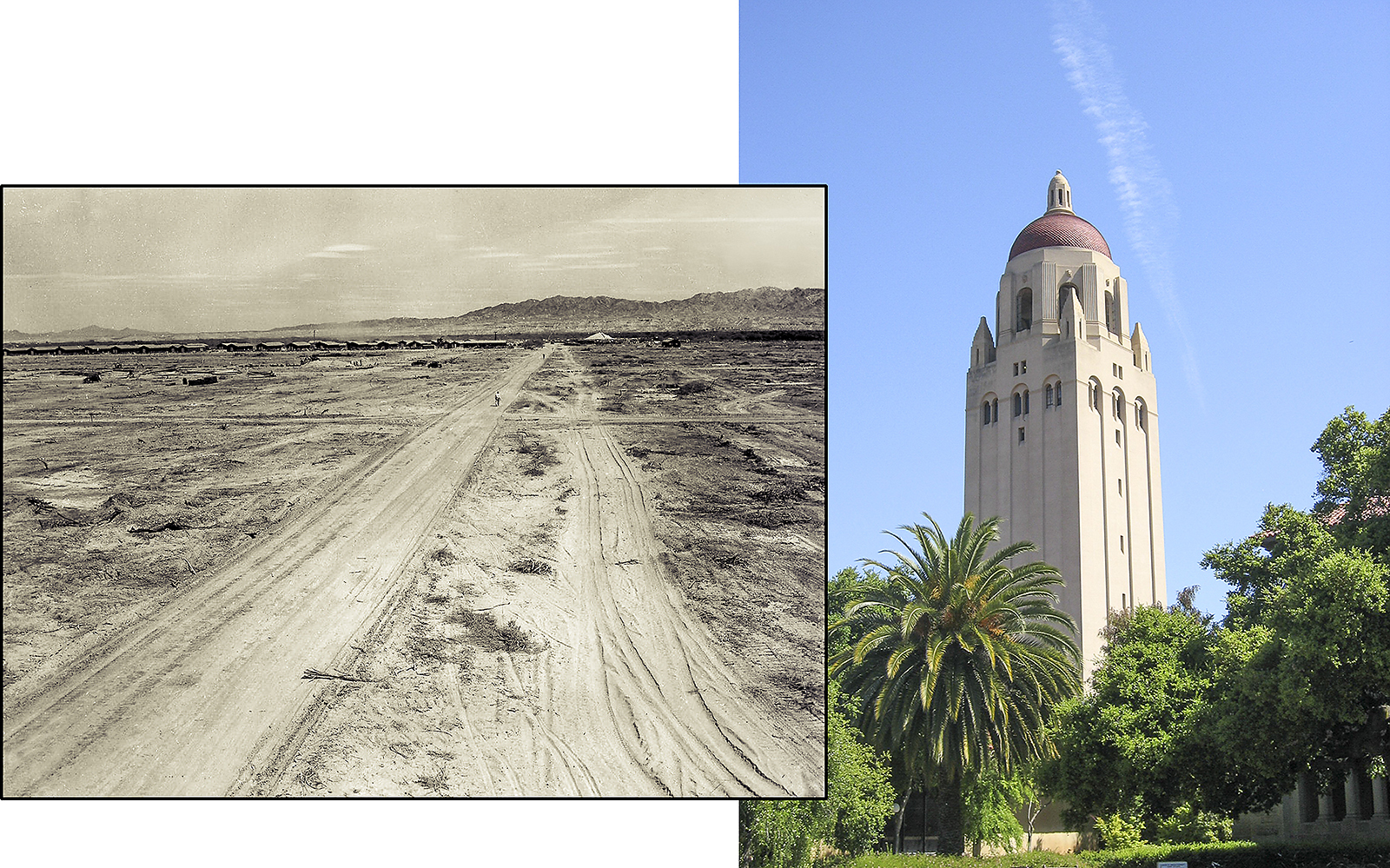

When Kitaji exited Poston on Sept. 12, 1945, he carried the Bible with him to the Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs, where he would oversee the arrival of some 150 people who would be arriving after their release from detention.

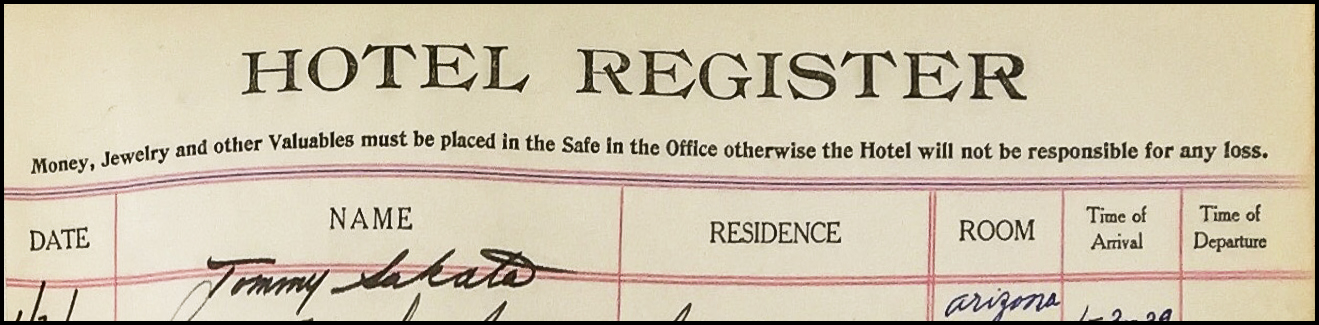

The hot springs was owned by Kyusaburo Sakata,11 who had purchased the property in 1938. He offered to make the property’s 22 cabins and healing waters available to help meet the urgent need for housing.

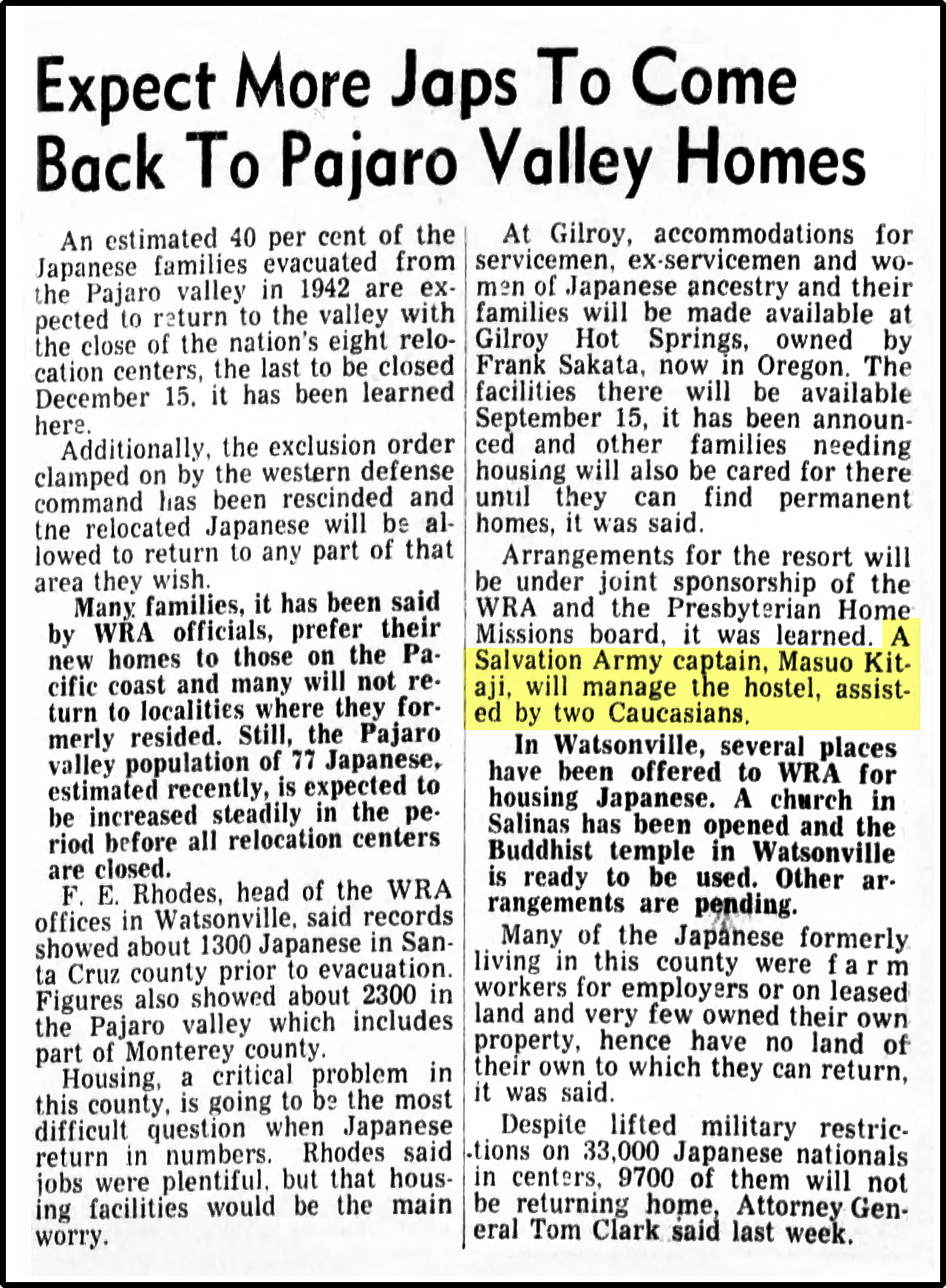

“Many of the Japanese formerly living in this county were farm workers for employers or on leased land and very few owned their own property, hence have no land of their own to which they can return, a newspaper reported.

The hot springs would reopen Sept 15 to help meet that need, the article said, and “a Salvation Army captain, Masuo Kitaji, will manage the hostel, assisted by two Caucasians.”12

The captain occupied one of the cabins and in later years received permission from Sakata to add space in order to create a “Church of the New Born.” Kitaji added a second story and cut holes through two floors and the roof to build around a living tree. Kitaji descendants remember their uncle’s services at what became the spiritual center of the hot springs.

They also recall him saying that he used a quill pen made from hummingbird feathers, but that may have been his playful storytelling nature at work: a calligrapher who studied his writing with a magnifying glass suggested that Kitaji may have used a technical Rapidograph pen.

Kitaji was replaced as hostel manager in 1947 with an experienced hotelier. He worked on the second Bible until his eyesight failed. He and Yuko had no children and Kitaji died in 1973 in Salinas, California. Yuko passed away in 1995 in San Jose.

Bibles for sale

In February of 2017, publicity about a unique WWII camp artifact, the Kitaji Bibles, began arriving in emails and voicemails around the country.

One recipient of the PDF brochure was a non-Japanese American who had supported a national protest in 2015 against the Rago auction company over its proposed sale of Japanese American camp artifacts from the Allen H. Eaton collection.

“Sadly, it is reminiscent of the Rago efforts with the Eaton Collection. We do not plan to contact the (seller) regarding their request to sell the items to us,” she wrote to a Rago protest veteran at the fledgling 50 Objects project.

A few emails later, the Kitaji family was alerted that their Uncle Captain’s Bibles were being sold by the New York firm. Within days, 30 Kitaji descendants –12 sansei and 18 yonsei — signed a letter demanding that the gallery remove the Bibles from the market.

“Your sales brochure opens with a 1944 photograph of Uncle Captain at the incarceration camp in Poston, Arizona, where our family was held behind barbed wire for more than three years,” the family wrote. “Two of us were born there. Using that photograph to try to profit off the unconstitutional confinement of 120,000 Japanese Americans compounds the original injustice and desecrates our uncle’s memory … We, the signers of the letter, are the living nieces and nephews of the Mr. Kitaji. You knew our names and birthdates since you have published them (in a brochure link).

“We ask you to clarify the provenance of these Bibles and the circumstances under which they were obtained.”15

The gallery immediately removed the Bibles from sale. The family was assisted by attorneys in negotiating the eventual transfer of the Bibles back to the family.16

The firm stated that the consigner of the Bibles had found them in a recycling bin in San Francisco in 2016 and sent them to Swann with instructions to sell to an institution. Finders’ laws in California require that the finder inform the police if the item exceeds $100 in value, which the consigner did not do, but this line of inquiry was not pursued. The Kitaji family does not know how the Bibles, once in the possession of the elderly Yuko, would have made their way into a recycling bin.

After the Bibles were rescued by Kitaji descendents, the family strove to find a safe place for their preservation while also making the contents freely accessible to the public. This led to an arrangement with the Japanese Diaspora Collection at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University whereby the Bibles would be stored in a vault for safe keeping while the copyright for the digital images would be held by the family. Four thousand pages were digitized by the Monterey District of the California State Parks and the images are now stored online, available to all, courtesy of the Hoover Library & Archives in Palo Alto, California.

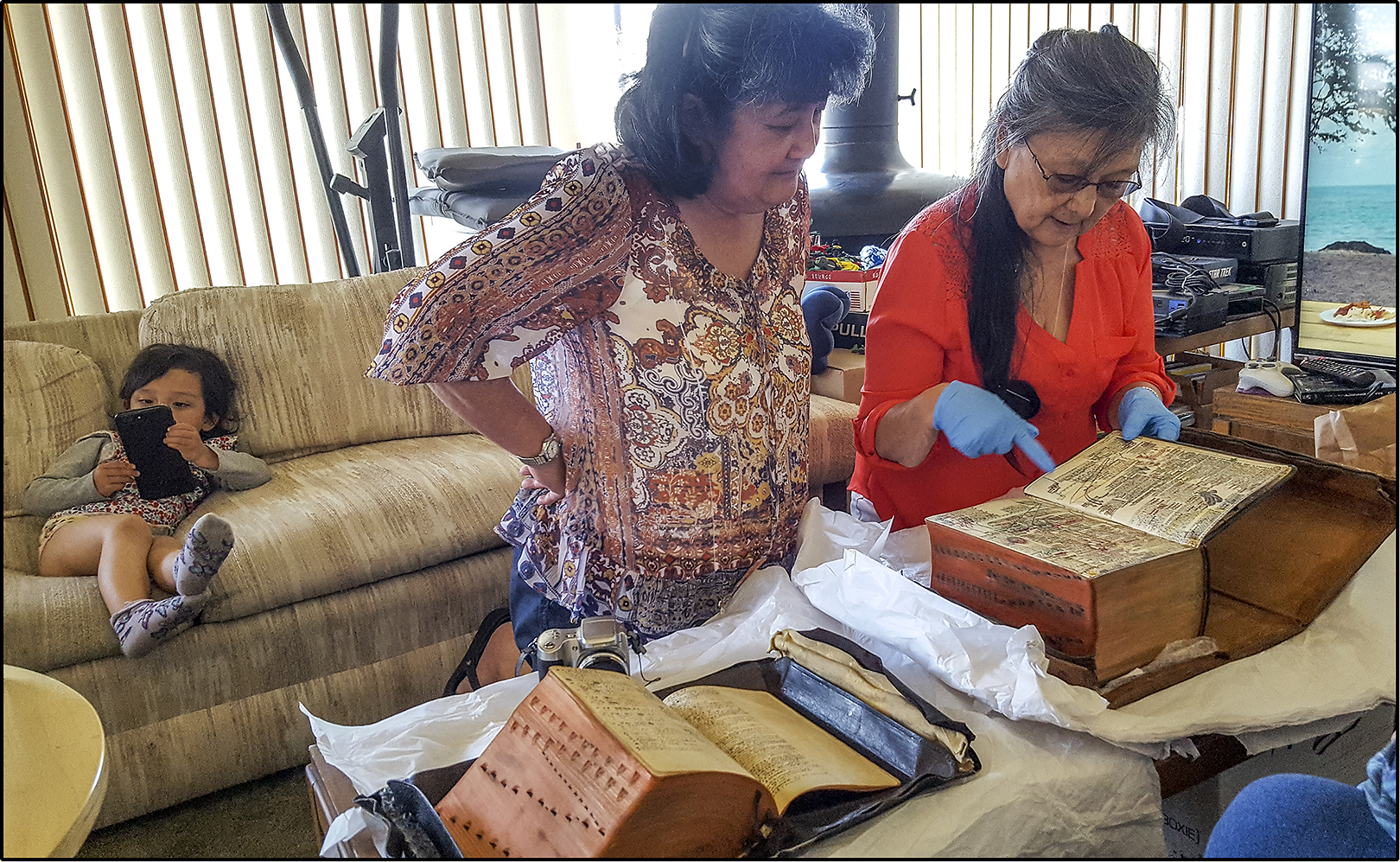

In May 2017, the annual reunion of the Kitaji extended family was joyous. Brian Taba, a yonsei descendant, had flown to New York to retrieve the Uncle Captain’s Bibles and brought them to the lunch. Kitaji nieces and nephews studied the pages they had not seen in decades. Young gosei, fifth-generation descendants played on the sofa, not expressing interest in their ancestor’s Bibles — yet.

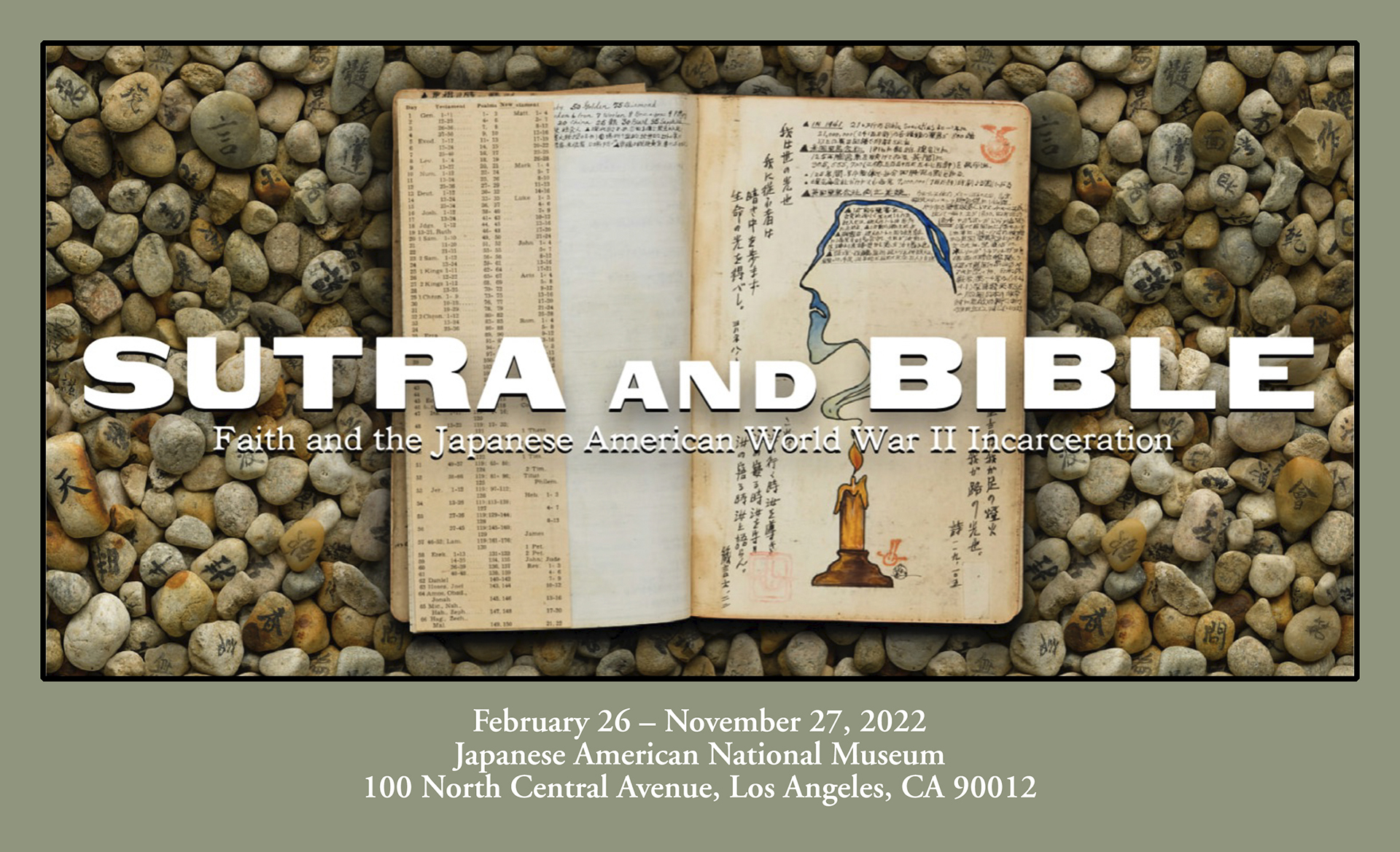

The hope of Captain Kitaji, that “my work may be remembered by Him and have some part in bringing real peace to the whole world” now begins its 21st century journey, on wide public display for the first time in an exhibition, Sutra and Bible: Faith and Japanese American World War II Incarceration,” at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

Sutra and Bible: Faith and the Japanese American World War II Incarceration is co-presented by JANM and the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture with support from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program and the Okada Family Foundation.

The exhibition is co-curated by Duncan Ryuken Williams and Emily Anderson,

Duncan Ryuken Williams is Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity, Chair of the USC School of Religion, and the Director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture.

Emily Anderson is Project Curator at the Japanese American National Museum and a specialist on modern Japan.

| The Kitaji Bibles | |

|---|---|

| dimensions | Bible I: 31.8 x 21.3 x 10.5 cm; Bible II: 30.5 x 22.9 x 14 cm |

| material | Paper, leather, metal |

| date | Bible I (1937-1944) Bible II (1953 - ca 1970) |

| type | New Analytical Indexed Bible, 1929 |

| languages | Japanese and English |

| author, creator | Masuo Kitaji |

| sites | Santa Anita, California, Poston II, Arizona, Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs |

| photo caption | Laura Kitaji Dominguez-Yon studies her uncle's Bibles. 2017. Photo b David Izu. |

Credits

April 8, 2022

by Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

Cover Images: All photos of the Bibles and their contents by David Izu, 2017. Photo of Masuo Kitaji courtesy of the Kitaji Family.

Special thanks to:

Laura Kitaji Dominguez-Yon, Brian Taba, Diana Kitaji Madalora, the Kitaji family, Duncan Ryuken Williams, Emily Anderson, Japanese American National Museum, Kay Ueda, Hoover Institution Library & Archives, Stanford University, Matt Bischoff, California State Parks, Monterey District, Densho, Shannon Maiko Takushi, Sharon Noguchi, Pine Ridge Association, Japanese American Museum San Jose, Gilroy Historical Society, Mary Ann Wight, The Friends of Calligraphy

Supported in part by The National Park Service

Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program