Not long after Kiyoshi Ina, almost three years old, recovered from the chicken pox and weeks under quarantine at the Tule Lake concentration camp, a package arrived in the mail.

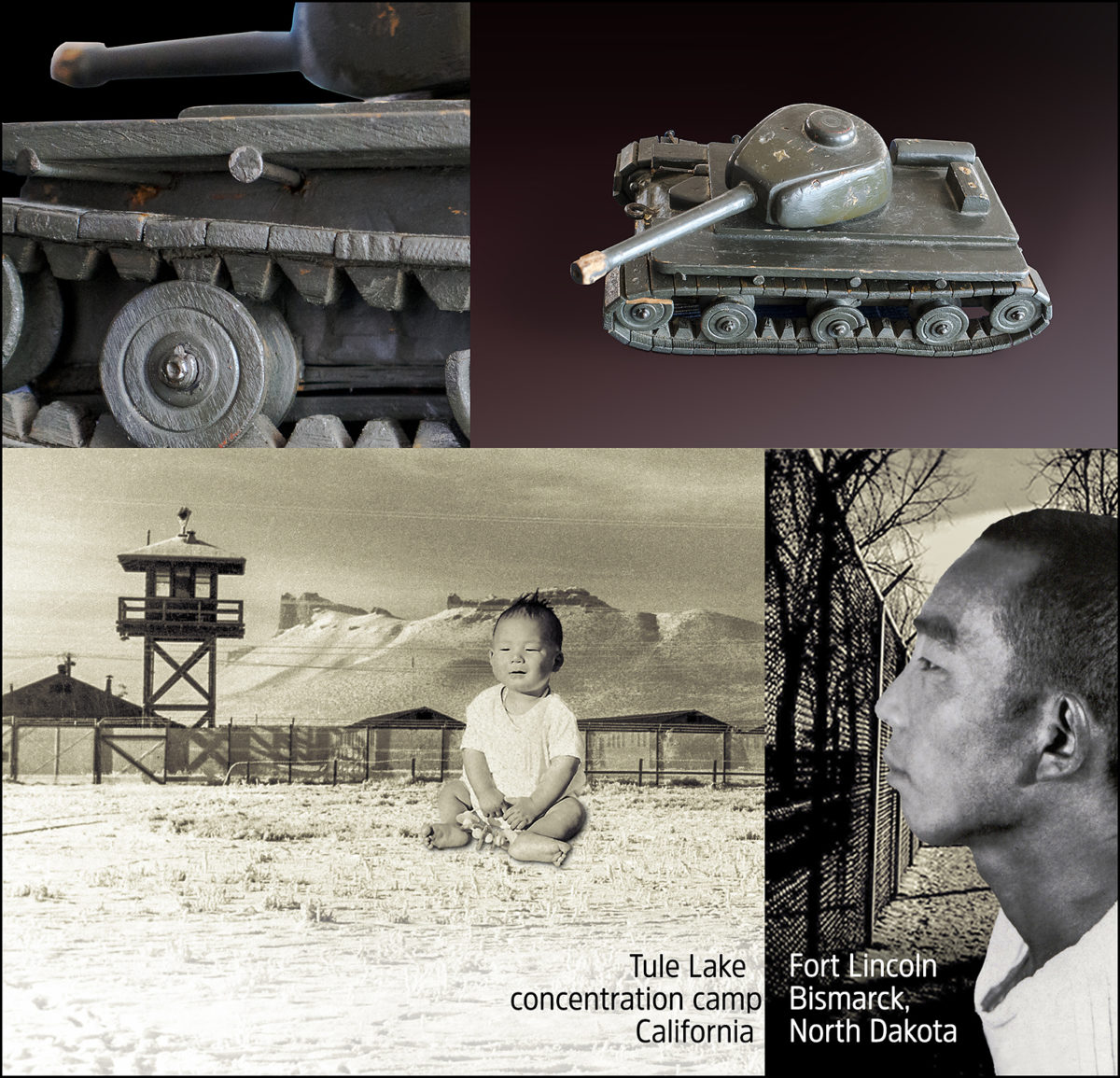

It contained a toy tank handmade from lumber scraps, wooden checkers and thread spools.

It had a gun turret that swiveled and moveable tracks that made a delightful clacking sound when the toy was pushed or pulled. At night, Kiyoshi fell asleep with it in his arms.

The toy had been lovingly hand crafted by his father, who was in a different prison camp some 1,500 miles away. In the absence of the father, the tank became a comfort toy.

The wheeled vehicle was also like a miniature version of the eight Sherman tanks that encircled the site where Kiyoshi, his mother and little sister were confined, surrounded by three layers of barbed wire fence and 24 guard towers.1

Before Itaru was seized and sent away, the family had spent two years at the maximum-security Tule Lake camp in northeast California, south of the Oregon border. The tanks were in place when they arrived in September, 1943.

So Itaru may have had tanks on his mind as he carved the toy in North Dakota.

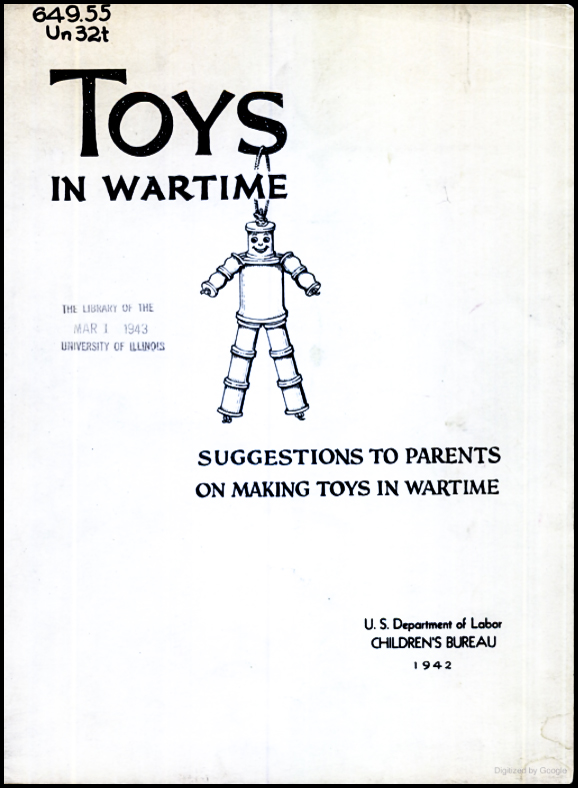

Toy tanks were a popular plaything during World War II, but the government stopped their mass production in metal so that critical materials could be directed to the manufacture of real aircraft and tanks.

Toy companies were converted into wartime production units and parents were urged by the government to make their own “Toys in Wartime,” the name of a government pamphlet that provided ideas for making toys using wood, paper, gourds, yarn and items from nature.

It was considered patriotic for children to play with homemade wooden tanks. It showed support for the war effort and signaled that toy makers were alert to the homefront need for rationing.

The emotions of Kiyoshi’s father, however, were probably more complicated than that. Itaru made the tank in the summer of 1945, from inside his fourth prison camp in four years while he was separated from his wife, Shizuko, their one-year-old daughter, Satsuki, and Kiyoshi.

While at Tule Lake, which had became a segregation camp for Japanese American dissidents in 1943, Itaru was a “no-no,” marked as disloyal to the United States for his negative answers to two questions on the government’s loyalty questionnaire. He and Shizuko, who answered similarly, were removed from their detention camp in Topaz, Utah, and segregated to Tule Lake. There, Itaru was locked up and brutalized in the camp’s jail for his resistance to camp authorities. The couple, both born in San Francisco, decided to renounce their U.S. citizenship and move to Japan with the children.

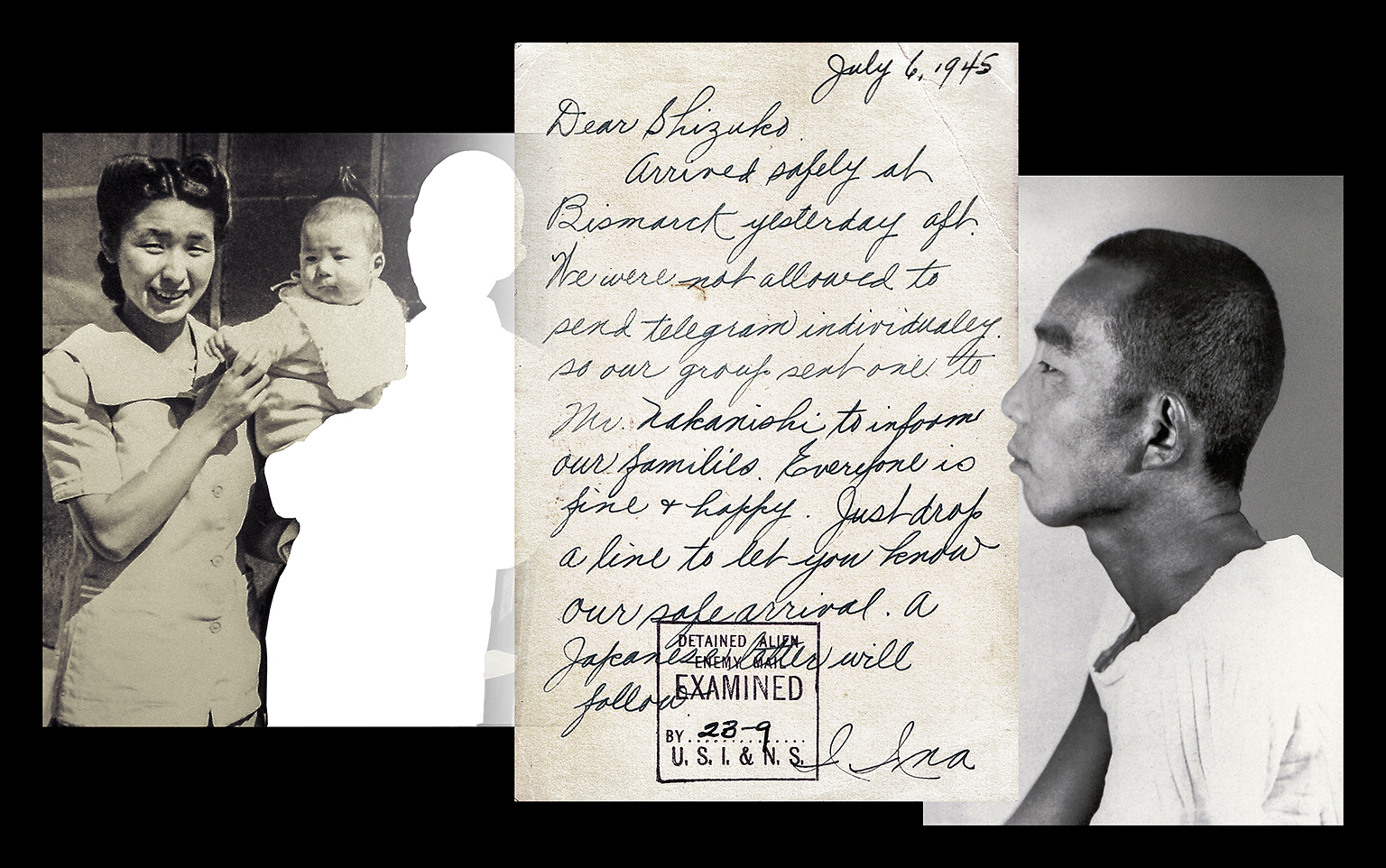

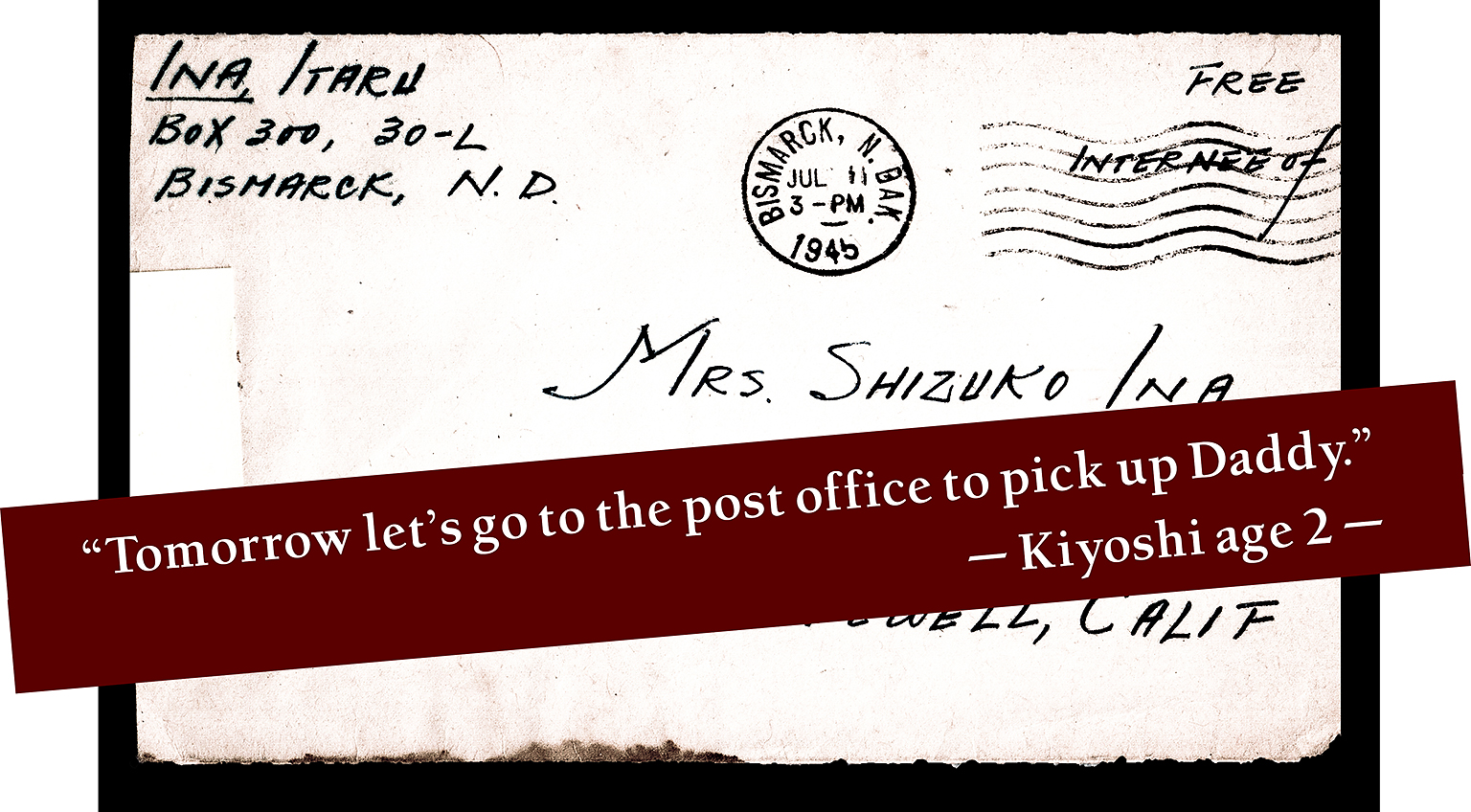

By July 1945, Itaru was transferred to the Fort Lincoln enemy aliens camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, throwing him in with Japanese immigrants, Japanese Americans and Germans.

Itaru wrote to Shizuko, on Sept. 6, asking after the children. He requested the carpentry tools that he had left behind in the barrack.

“I’m glad that Kiyoshi is finally completely well. But you said Satsuki has chicken pox so this will be another hardship for you. Yesterday I sent two pair of geta (wooden sandals) and the toy tank. I’ll be able to do carpentry work since friends who have repatriated gave me lots of wooden boards….if it’s convenient…send me the carpentry kit. I need it for making the toys.”

Shizuko replied on Sept. 11:

“… I appreciate the trouble it took for you to send many things such as the geta, tobacco, tennis ball, toy top, toy tank, etc. I was surprised to see how well you made the tank, geta and top. Kiyoshi is very happy. I wish I could show you his happy smile. Last night he took the tank to his bed and slept while holding it. I don’t know what he was thinking, but before going to sleep, he kept asking me, ‘Why didn’t my Daddy come home with the tank?’ Then he said an innocent thing to me, ‘Tomorrow let’s go to the post office to pick up Daddy.’ He made me laugh and cry.”

Woodworking was a popular pastime at the WWII Japanese American detention camps. Prisoners made wooden geta sandals, decorative carvings and furniture for the unfurnished barracks.

At Fort Lincoln, German soldiers were known to provide technical advice to Japanese American woodworkers who passed the time making prison art or what might even be classified as a type of “trench art.”

But Itaru already was an accomplished woodworker. Kiyoshi never talked to his father about the tank, so he doesn’t know the details of how it was made or what model it was. He thought that it might be an American design because of the star on the turret and because Sherman tanks encircled Tule Lake.

Visual analyses by experts, however, suggest that the toy is more likely to be a replica of the legendary Soviet T-34, considered the best tank of WWII. Did Itaru study a news photograph of a T-34, which had been so successful in vanquishing the Germans?

Laura Haendel, curator of the Deutsches Panzermuseum Munster wrote: “Judging by the high level of attention given to fabricating a rounded turret and evenly distributed road wheels I would say it’s a Soviet T-34 tank, maybe a later model like the T-34/76 or T-34/85.

“The extra fuel tanks on the side of the hull are characteristic of a Soviet tank, too. The only thing that doesn’t fit is the muzzle of the tank gun (and) some details like the placement of the MG mount on the front plate … but this is a child’s toy, after all.”3

The Ina toy, with its intricate moveable tracks, is “rather extraordinary,” she said.

The Inas eventually withdrew their plan to move to Japan. Before they arrived at that difficult decision, Itaru had been transferred to his fifth camp, in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The family finally reunited in south Texas at their last incarceration site, in Crystal City.

In 1946, the Inas were released from Texas and moved in with relatives in Cincinnati, Ohio. A third child, Michael, was born there. The family of five returned to San Francisco around 1950, and at some point, the tank was unpacked. After Itaru died, his wartime letters were found and Shizuko realized that she had saved her letters to him. The tank’s story emerged.

After the war, Itaru and Shizuko did not talk about the years of incarceration or their acts of dissent against their unconstitutional confinement. They discouraged their children from getting involved in the social protests of the 1960s. The trauma of speaking out silenced Tule Lake resisters long after the war ended.

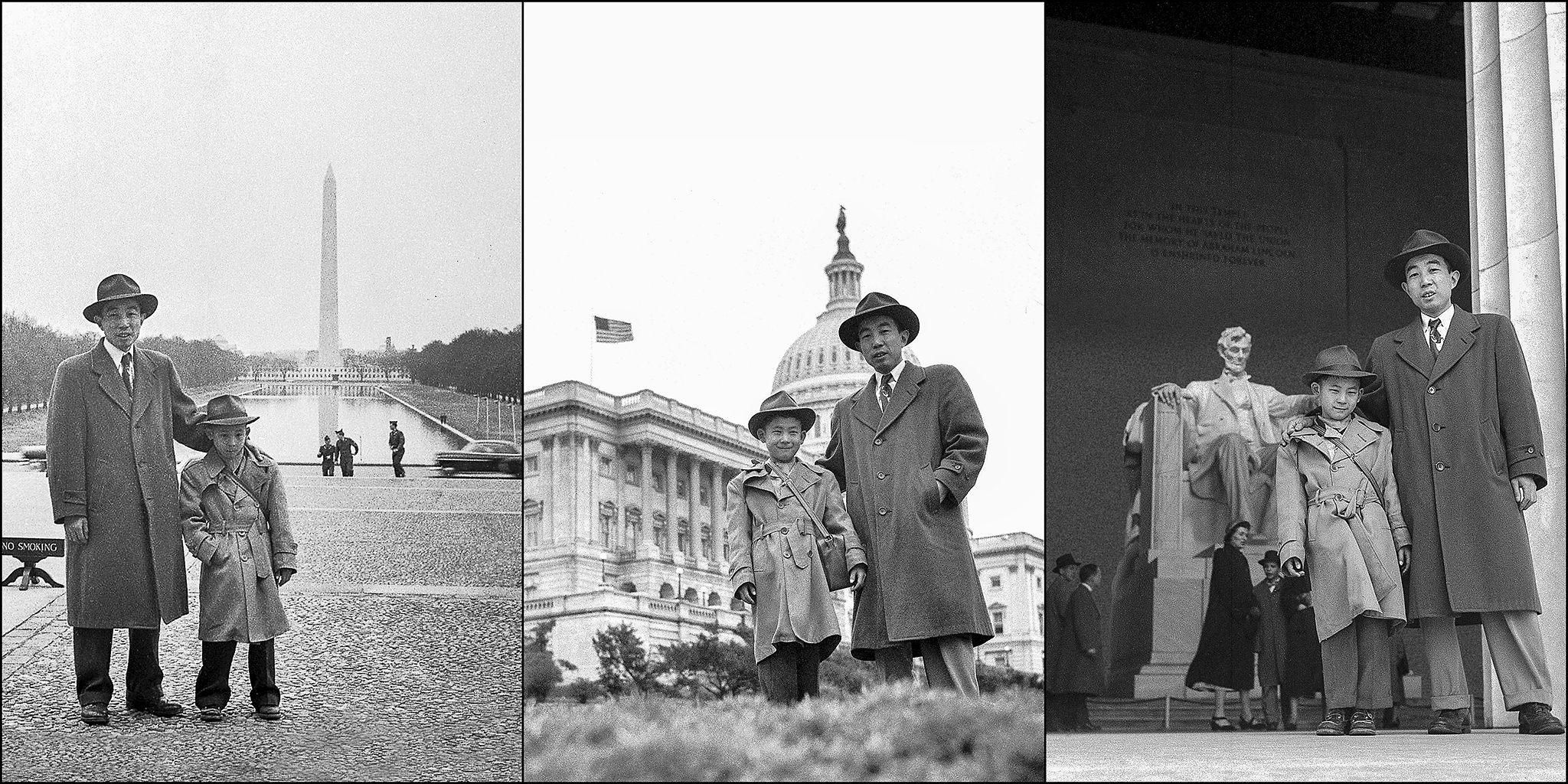

In 1952, when Kiyoshi was nine, Itaru took him to the East Coast for an extended road trip to “all the patriotic and iconic sites,” Kiyoshi said. The two started at Niagara Falls and traveled south to Grant’s Tomb, the Statue of Liberty, the Liberty Bell, the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument and Mt. Vernon.

“He was a no-no boy but he loved his country. He renounced his citizenship because he was upset with America and the policies they put on the Japanese Americans,” Kiyoshi said. The trip “told me that he loved his country. And that he wanted me to love it, too.”

Today, Kiyoshi is 77. His father passed away at age 64, in 1977. Shizuko died at 82 years in 2000. Every Father’s Day, Kiyoshi posts images of the East Coast trip on his Facebook page. On his birthday, he remembers his mother by sharing photos of his early years at Tule Lake and Topaz, Utah, where he was born.

In recent years, he has become an activist on behalf of detained children held in cages at the U.S. southern border and the hundreds of babies and youth who have been separated from their parents because of U.S. immigration policy.

He has carried paper cranes, or “tsuru,” to the barbed wire fences of migrant detention camps with the Tsuru for Solidarity activist group, to protest child detention and what he calls 21st century concentration camps. He is joined by millennials and Japanese American camp survivors now in their 70s, 80s and 90s.

The toy tank was featured in an exhibition in 2019 in San Francisco, titled “Then They Came for Me,” which featured photographs and artifacts of the Japanese American incarceration years. The intent was to remind viewers that history repeats itself and that the lessons of the camps, including the complex story of a child’s toy, must continue to be heard.

Meet the Ina family. This Saturday, Nov. 7, Kiyoshi Ina, his spouse, Akemi, and his siblings Satsuki and Michael, will discuss the toy tank, childhood memories and the effect that the war had on their families in an online program sponsored by the National Japanese American Historical Society and 50 Objects, from 11 a.m. to noon. Register for the free program here.

| Kiyoshi's Tank | |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 11" x 6 1/4" x 5" (length with cannon: 13 1/2") |

| Material | wood (10 thread spools, 11 checkers, scrap wood), metal, paint |

| Weight | 2.9 pounds |

| Date | August 1945 |

| Creator | Itaru Ina |

| Site | made at Fort Lincoln, Bismarck, ND, mailed to Tule Lake, California |

| Collection | Ina family collection |

| Photo | Kiyoshi Ina with tank, Oakland, California. |

Credits

by: Nancy Ukai

art direction: David Izu

banner cover images: David Izu, various unknown photographers courtesy of the National Archives and the State Historical Society of North Dakota. Photo illustrations by David Izu

Special thanks to: Kiyoshi Ina, Satsuki Ina, Laura Haendel, Deutsches Panzermuseum Munster, Stuart Wheeler, The Tank Museum (U.K.) American Armory Museum, Pat Fitzpatrick (Tule Lake Scrapbook, Facebook), Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Anthony Hirschel

Supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service Japanese American Confinement Sites program